On the importance of building relationships

Prelude

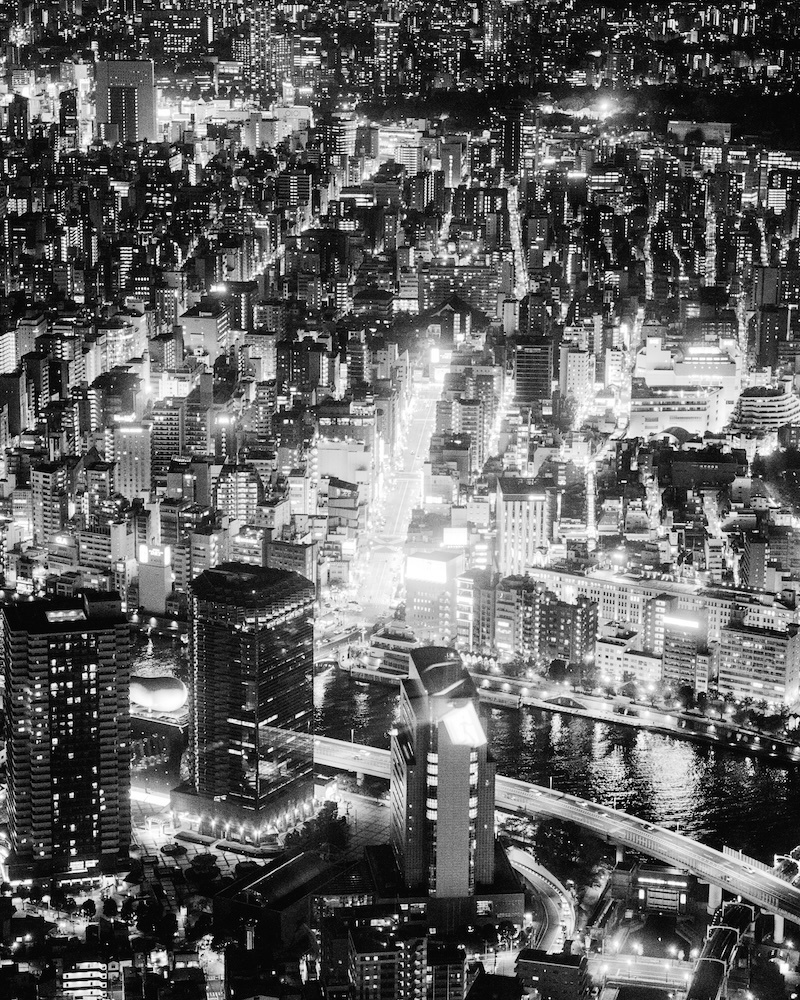

Daniel Dorsa is a Los Angeles based photographer who works across portraiture, fashion, landscape and visual reportage. Always present in his work is a clever interplay between photographer, subject, light and place that emphasizes the richness of the human against an ever-looming backdrop of banality.

Conversation

On the importance of building relationships

Photographer Daniel Dorsa discusses accepting failure, building relationships, and staying present.

As told to Jeffrey Silverstein, 2534 words.

Tags: Photography, Process, Education, Collaboration, Income, Beginnings.

How did skateboarding set the scene for where you’re at today?

That’s my first love. I owe my entire life to it. I would be a completely different person if I didn’t start skating when I was young. I got interested in photography in a roundabout way. When high school came, I wanted to do a creative elective. I was like, man, I’m just so bad at drawing. Some of my friends were really good at drawing and painting, it kind of discouraged me. I wanted to try something I knew nothing about, it made it more exciting. So I was like, oh, there’s a photography class, let’s give it a try.

I got hooked. At the start I was shooting photos of my friends skating. I was okay at skating, but some of the kids in the scene in South Florida were amazing, phenomenal talent. We’d be going to spots where I’m like, “I have no business skating this thing,” this big rail or stairs. I’m like, “I’m not good enough for that,” but I can bring the camera and now I have a reason to be here other than just being the homie on the session. Now it was like, let’s do something with this.

You became the de facto photographer.

I got decent at it. People would make a point to say, “oh, you should come. I want to do this hard trick. I want to get a photo of it.” When I was young, I saw that as my path forward. Later in life I did an internship in California for a skateboarding magazine. I realized I didn’t want to do it anymore, the skate thing, but wanted to stay with photography. I left, went straight to photo school and started learning anything I could. That’s how my trajectory changed.

Skating was the foundation of work ethic for me. You work really hard and fail a lot. You’re always eating shit, you’re going to fail every single time you go out. You’re not going to land all your tricks first try. You’re constantly working at it, trying to evolve and push yourself. There’s a little bit of madness to that repetitive nature. That reflects how I approach my work now and how I pushed my career forward, always accepting failure and learning from it.

What lessons stayed with you?

When you’re shooting skateboarding, you have no control over your situation. You might not be allowed to skate there, usually you’re not. You have to make decisions quickly. You have to go through an instinctual process: how can I make them look good? How can I make the trick look exciting? You might get five or ten minutes, then you get kicked out. That idea connects to my career now, shooting an editorial where someone says, “okay, you’re going to shoot a celebrity and you have five minutes.” You need to make this look really good with the limited time that you have. It’s kind of the same thing. You’re like, I don’t have a lot of control, so let me try to make the control I do have super dialed, make decisions on the fly when things change and lean into that confidence of making those decisions.

What changed when you went back to school?

I was going to a community college with a great photo program. I always joke with my wife because she went to Parsons and her facilities were the same as mine, even though I paid nothing. I was hyper-focused on this niche thing, skate photography. It was so niche that I had no expanded world of photography outside of that. I didn’t know classic photographers. I didn’t know the history of photography. I was a blank canvas. School is a hard place to learn technical stuff that applies to a career later, at least in photography.

The biggest thing was getting access to a photo library and seeing other students trying different avenues of photography that I never even thought about. I never considered what a fashion shoot looks like. There was a kid in our school who was super into architecture. I didn’t know that’s an entire industry.

You also started taking portraits of musicians early on.

Growing up I was always a big admirer of music, no music talent in my body at all, but a big admirer of it. A bunch of my friends in college were musicians, I loved to go to shows. Some friends would be like, “oh, hey, I need a press photo, would you take it?” I didn’t know I liked portraiture until then.

Which is now something you are hired for regularly.

It’s super weird how I had no intention of that and then was like, oh, not only am I getting pretty good at this, but I actually really enjoy it. I always liked connecting with people regardless, but then I also got an excuse to be in their world for a little bit. I get a hall pass where a lot of people don’t get access.

You’ve described yourself as a reactionary photographer. What does that mean for you?

There’s two main disciplines. You’re the sculptor or the painter where you’re concepting an idea and executing exactly what you have envisioned in your mind. Then you’re the hunter. Your street photographers, documentary people, the photojournalist. People out there looking for the picture. They’re not trying to create the picture themselves.

There’s a Venn diagram. You can be a little bit of both. I fall somewhere in the middle where I don’t like sculpting an entire scene to make it perfect because my mind doesn’t work that way. I like to work in a broad concept and not into the granular like, “I need this person to move their head two inches this way otherwise the photo is terrible.” I’m not like that. I like to have a collaborative experience with the person that I’m working with. If it’s not a person, a landscape or something, I want it to give me what it wants to give me and then I react to it. For a hypothetical portrait setting, I come over, I’m shooting someone in their home and I find a room, a corner or a scene in their home that I’m attracted to, whether it be the light, the layout, whatever. Then I place them in there and see what we can make within it as opposed to thinking of the exact pose they need to make ahead of time and seeing what that person brings themselves.

That ownership of posing and getting them into a specific thing comes to me, but I still like to observe them while we’re working. A lot of times people do beautiful, nuanced facial expressions or poses they’re not even thinking about. I see that and I react to it. I’m trying to capture those in-between moments as much as I can. It becomes less formulaic. I need to be as present as I can. That keeps me engaged with whoever I’m working with.

How do you build trust quickly with your subjects?

It depends on who it is and how you’re coming about it. With the person who’s never got their photo taken before you kind of have to treat it like when you go to the doctor and you’re kind of nervous. They’re telling you every single thing they’re doing, I do that. I’m like, “okay, we’re going to do this, and the reason why we’re going to do this is because of X, Y, and Z.” I try to be really explicit and have them feel like they’re in control and have a part of the process. Once it starts going, they usually feel a lot more comfortable. You have to keep the communication going. The more you talk to them, the more they forget that there’s a camera in their face. The more you sit in silence, the more their mind is going to drift on every imperfection about them. There’s nothing to actually worry about, but that’s where their mind is going. Sometimes even having another person with you, an assistant, they can have a conversation with them. That’s an easy trick that can help.

Is there a moment you can pinpoint where you realized you could support yourself entirely from your work?

After I dropped out of college, I moved to New York when I was 24 and the first job I got, I worked at a photo studio working in an equipment room. I worked there for a little over a year. After that I moved from working at that studio to becoming an assistant on set, working under a lot of photographers. That’s where I got all my technical chops. I was like, “oh, this is how you light something in a real, professional way.”

Also learning the soft skills. This is how a set works. This is how you talk to a client. This is how you talk to an art director and not be a fucking asshole. I saw a lot of failure as an assistant with no responsibility to any of it. I’d notice it and remember not to do those things. You can start understanding the dynamics. Not as much as when you’re in the hot seat yourself, but you get a good base. I assisted for about three years. That whole time I was building my portfolio. I had a lot of musician friends, those were the base of my portfolio. Then I started reaching out to magazines, newspapers, doing portfolio meetings, slowly working my way up. I remember in 2017 there was this moment where I transitioned. I said, “I’m not assisting anymore. I’m just shooting.” I was starting to get a lot of inquiries. It was a slow progression every year, making a little bit more money, shooting a little bit more, booking a few more jobs.

How do you balance personal projects with your client work?

Every project has three buckets you want to fill. There’s a financial bucket. If this gets filled I’m like, “I don’t care what we’re doing, we’re going to secure the bag, we’re going to do this even if it’s not the most glamorous shoot.” Like most working photographers out there, I shoot plenty of stuff that lives on a hard drive that no one’s ever going to see. People are going to see, but they’re not going to know it’s mine. There’s nothing wrong with that. When I was younger, I always thought like, “Oh man, look at this big photographer. I love their work. All they do is do cool shit.” Those people don’t always do cool shit. They do dumb stuff too, you just never see it.

Then there is a portfolio bucket. If a project is interesting and you have the potential to make something really good, then it’s worth doing regardless of the other buckets.

The third and final bucket is relationships. Maybe I don’t like this project, but it pays okay and I really like this art director’s work in general, then I want to do it because I want to work on the relationship. Maybe this isn’t the best shoot for me, but you never know where that person might end up, where there’s something perfect for you down the line. That’s happened to me a lot where I have worked with someone when they were more junior somewhere, whether it be a photo editor at a publication or a more junior art director, then they move on, become senior somewhere else, and then they hit me with one of the best projects I’ve ever done. That one’s a little bit more of a gamble, but it’s important. You have to recognize building relationships is the entire industry to a degree.

That goes back to skateboarding again where you are making a million decisions per moment.

Absolutely. The less decisions I have to make on set, the better work I get. Sometimes even on gritty stuff with budgets where it’s like, “Hey, we only want to have one assistant,” or something like that. I’m like, “No, I want two or three people or four people working with me because the more work that is put onto them for me not to think about, the more I can think about what to make the best version of this image is.”

Do you keep a consistent crew?

I try to work with the same people often. Consistency is important. Sometimes my first assistant’s free, but my go-to second or third assistant is not available. Then I’ll defer to my first like, “Hey, you hire who you want to hire because I’m going to be interacting with you as my first a lot more than I’m going to be working with the other people.” I’m not going to be communicating with them as much. The chain of command goes down kind of like a chef to a degree. If you’re a head chef and you work with your sous and the sous is barking orders to everybody else. Kind of works the same way. The head chef just needs the sous and them to be aligned, then everybody else can fall in line.

What do you do to get out of your comfort zone?

Something I’ve been doing to get me out of my own bubble over the past few years is digging into photo books a lot more. That’s been such a better way of gaining inspiration than going on Instagram or anywhere else. I love photo books. I always have, but I was always too poor to be able to afford buy them because they’re fucking expensive. Here in LA there’s Arcana books on the west side. It’s basically a library, their photo books section is huge. A great place for inspiration. When you look on Instagram and you see a shoot that someone’s done, you’re just seeing the very best of this little thing that someone did. When you’re looking at a photo book, it’s more like listening to an album where you’re listening to the record straight. You’re getting the whole picture of this artist’s point of view and what they’re trying to convey. It inspires me to think about work in a more complete way.

Daniel Dorsa recommends:

These are five photos books that I’m finding a lot of inspiration from lately. While these may not be my all time favorites, I’ve been repeatedly sitting with these currently. I strongly encourage to go find them locally if you can.

- Name

- Daniel Dorsa

- Vocation

- photographer

Some Things

Pagination