As told to Ken Tan, 2710 words.

Tags: Photography, Film, Beginnings, Success, Day jobs, Failure, Process, Inspiration, Money.

On choosing your path and enjoying the journey

Photographer Simon Harsent on getting started almost by mistake, learning from failure, developing a personal style, juggling the commercial and the personal, and the importance of a community.How did you get into photography?

I grew up in a small town about 40 miles outside London in a working-class town called Aylesbury. With my father being a poet, I enjoyed a very different kind of upbringing from the standard blue collar family. I grew up surrounded with books about art. Encouraged by my father, I started painting when I was 11. At 13, I picked photography as an elective in school. I’ll be honest with you, I just thought it would be an easy subject. But once I saw that first print come out in class, it just changed my life. After school I went to Watford Collage to study photography but left before the end of the second year, and got a job working as a photographer’s assistant in London. I was 18, and that was what started my path into being an advertising photographer.

What did you do as a studio assistant?

I was loading film, sweeping the floor, making cups of tea, running to the lab to pick up film. I never worked so hard in my life. You’re in an hour or two before the photographer gets there to clean up from the day before. You leave half an hour after he leaves. The days were arduous but that was how I was learning my craft: lighting, different film types, color balance and all that kind of stuff.

The Beautiful Game by Simon Harsent

Why did you move to Australia?

I came to a stage in my life where I just wanted change. Also I figured if this was going to be what I was doing for the rest of my life, then I knew that once I went freelance, I would not be able to take my foot off the gas. This was probably my only opportunity to take a year off and see the world. So I got a six month travel visa to Australia, which I extended after six months. I found a shared studio and started ringing the contacts of people whom I had been recommended: “Hey man. I’m Simon, a photographer from England in town. Can I come and show you my portfolio?”

You must have been pretty determined at 21 to go to a different country and try to set something up.

You don’t really think it through at 21. You go, “Yeah. Fuck it. I’m just going to go live in Australia.” And then when you get there, you deal with surviving. I think that’s a better way for me to operate in every aspect of my life. I make a decision and tell everyone I’m going to do it, so that if I don’t do it, I’ll look stupid. We are not risk-averse like analysts. You work it out when you get there. I think that’s what it is like to be an artist anyway. When you start a project you just let it take you where it takes you.

When did photography get serious for you?

Commercially, it was a job for the Honda Prelude launch campaign. It was more money than I had ever earned in a year before. That just turned everything financially. I opened a studio in 1989 and focused on making it successful commercially, because I knew that if I didn’t earn money through commercial work, I was never going to have enough to produce my own work.

Has it always been advertising?

For money it always was and has been Advertising. I call it my day job. The many photographers whom I assisted were primarily working in advertising, so that was the world that I knew. When I decided to freelance I would cold call my list of art directors to show my book. Personal work was always something I’ve done even when I was primarily an Advertising photographer. Once I’ve shown my book to everyone, I would work on more personal work so that there was always new stuff to present.

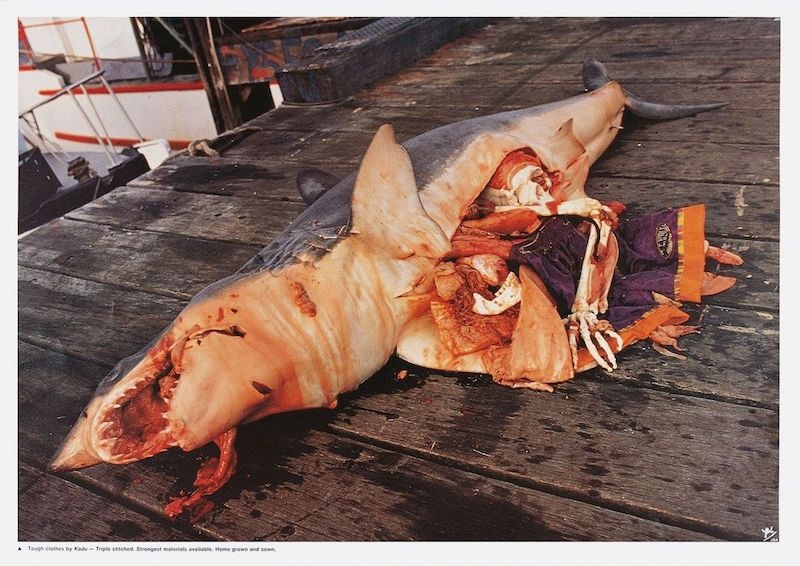

Ad for Kadu brand surf wear, winner of the Cannes Press Grand Prix, 1994. Image by Simon Harsent

How did you find your edge?

At that time, advertising was really stagnant. Cameras were always on tripods. Everything was technically perfect. Some of my failures were actually the best things that ever happened to me. They had a kind of edge that revealed who I really am. I could sit there for 20 hours trying to light something, but I could never be as good as other photographers because, A, they had better equipment; B, they had many more years of experience.

Looking at what my strengths are I started being a lot looser, a little more punk. It reflected my background more as opposed to the super slick advertising of the ’80s, which I felt was completely over art directed and controlled. That said, with my experience I still could do the complicated technical images, but with the advantage where I wasn’t afraid to shoot things out of focus or stuff like that. It was also serendipitous that that became a style people started to resonate with.

It was probably in the mid-‘90s when I started to make a name for myself. The ad I shot for Kadu Surf Wear. It showed a shark with its gut cut open, and there was a skeleton in it. Only the Kadu board shorts had survived. It was so different from everything else that it cleaned up all the international awards shows, and won the Cannes Grand Prix for print. That was the first print Grand Prix for Australia.

Must have been a game changer?

That was when jobs started to constantly come through my fax machine. But I was always kind of bizarrely taken by that, because when I looked at my portfolio, nothing had changed. I was the same person that showed Art Directors the same portfolio six months ago. But what changed was people’s perception of me because I’ve been involved in this campaign that has won the prestigious Grand Prix. It was then I thought well if this business is all about awards then I’ve got to win as many awards as I possibly can. Thus, I’ve had my fair share of advertising awards over the years.

What good were awards?

It afforded me the opportunity to work with some great people on campaigns. There was an art director, Bobbi Gassy, who changed my life. He taught me so much about craft, and the understanding of how to work an idea, how typography and photography should exist together. There was also Mike Chandler, who was an absolutely major typographer in Australia. He would always say, “Glass bottle, bottle glass,” which was a nice way of saying, do the client’s thing, then do your thing.

You find your tribe, the people that you need to be working with. Everyone has this common goal, so I was not just the supplier anymore, but part of a team. Like you and Jon when we worked on Melt. You guys were the perfect people for that. It was this incredible book and website. I really believe that the path you choose in life puts you on a certain track, and there’s something cool you’re destined to make.

Melt - Portrait of an Iceberg by Simon Harsent

Right. So what paths took you to Asia and New York?

I started getting calls from ad agencies in Asia. Singapore was a great thriving market used to paying expat photographers well. I did great for a while but I felt I’d gone as far as I could go then. I was winning a lot of awards and constantly featured in Archive Magazine. Then the opportunity to work in America opened and it just felt like the right place. The budgets in America were just unbelievable. I think also there was a bit of ego there: I want to play with the big boys.

Yeah. But it’s deja vu, isn’t it?

Yeah. It is. I always love a new challenge, to shake things up, never wanting to fall into a routine. It’s okay to be very well regarded in Australia, but in the grand scheme of things, what does that actually mean? My son was one and a half. I figured if I go to New York for four years, it’s going to have the least amount of impact on him. I moved to New York in 1996, and stayed for 20 years.

New York was buzzing. I was in my early 30s and it was great. I had an apartment in Soho on Broome Street. All of a sudden I had a lot of free time I never had before. I’d go for a walk with my camera, but did not know what to shoot. Having been an advertising photographer with a brief for so long, I found I couldn’t shoot without a brief. It freaked me out. Realizing I was going to have to brief myself, I started working on more personal projects.

What’s the difference between a personal project and a commercial project? Can you, as a creative, operate without one or the other?

It’s interesting because in an ideal world they should both feed each other. The big difference is that with commercial work, I was shooting within defined parameters designed by someone else. With personal work, defining these parameters for yourself is useful to stay focused. Then there is more clarity to look at why, how, or what you’re going to do rather than just aimlessly walking around with a camera.

Portrait of Seamus Heaney by Simon Harsent

I think your portraits are fantastic.

It’s always something I’ve struggled with as well. As a young photographer I wasn’t confident behind the camera when shooting portraits. As I improved technical aspects of my work I concentrated on the interaction with the sitter, and worked out what I wanted from the session. Once I stopped trying to make it perfect, stopped trying to achieve the Rembrandt lighting and went more towards more of a Van Gogh expression, I suddenly got it.

I’ve always wanted to make a portrait I could never remember taking. To look at the image after and not be able to remember where the C-stands were, where the background and the lights were. The trouble with one’s own work is that you never get to see it with fresh eyes.

Do you ever say “no” to a project?

As a photographer, you’ve really got to know when something isn’t right for you and to say “no.” If you don’t, those decisions will be incredibly harmful for your career. I know it’s hard. These days, jobs are few and far between. You might be sitting there, you haven’t worked for a month or two, thinking, “Oh shit, I need a job, and something comes through.” Mark my words, if you do the wrong job just for money, you are going to knock your career back even more.

With all this experience, was this why you started POOL Collective with Sean Izzard?

Even though I was living in NY, I traveled back to Australia every school holiday to see my son, Declan. In 2008 I started working in Australia more to spend time with him, who was a bit older. I felt there was something missing from the industry then in Australia as far as production and representation was concerned. Sean Izzard and I talked about setting up a structure to help new photographers who, just like us when we were starting out, might be in need of guidance.

We started POOL Collective to help develop careers and offer practical advice: how the business worked, how budgets are structured, how production was managed. The basic stuff. But most of all was the strength in supporting each other as photographers, that was really incredibly important. It turned out to be probably one of the best decisions we’ve ever made. We’ve now got an amazing support structure of incredible photographers.

In the age of social media, what do you think the status of photography is now?

To quote Dickens: “It is the best of times and the worst of times,” it is the best of times because there’s more people than ever who look at photography. The worst of times as there has never been so many uneducated people looking at an art form and having an opinion. There’s so many people out there producing work. For instance when the bush fires happened in Australia, every man and his dog were out there with a camera. Social media’s littered with it. It has become a noisy, disposable world and I wonder how much great work is going to get lost in the clutter.

To me, Instagram is the difference between traveling on a fucking high speed train out of Tokyo, where everything’s just flashing by in a second and you’ve forgotten it as soon as you saw it, as opposed to walking down the path to connect with the environment you’re in. In that quickness, we lose a little bit on the contemplative aspect. It desensitizes people. You lose complete perspective and the ability to look. The beautiful thing about art, like poetry, is that it is open to interpretation. You read the poem and get a sense from reading that. You’re making the story up yourself.

Flood outside Buckley Street, 2020. Image by Simon Harsent

Your studio was recently affected by the flood, tell me what happened.

We had a massive downpour of rain in Sydney. The whole street where my studio was went underwater due to storm drains not being able to handle the unprecedented amounts of water. My studio space, where my wife Lida had her sculpting studio and Declan, his recording studio, was inevitably flooded. Water was just pouring through the backdoor, soon the whole studio was under two feet of water.

It’s so weird to think about it now. I was trying to salvage the situation while cars were floating down the street. You’re incapacitated. I was just standing there with water pouring in.

Did you lose much?

I was lucky, I didn’t lose everything, but I did lose over 100 pieces of art from over my last four exhibitions that spanned 20 years. Luckily I had already gotten my cameras and hard drives in my car by then. I called Declan and loaded up as many things into the truck, including a few of his guitars. Then it was like, fuck, what can you do? You just have to lock up and leave it. Outside you could see the emergency services on the street trying to stop cars from floating down the street. It was surreal.

The guys at POOL got together and did a fundraising auction for me. They grabbed 12 of the damaged prints from the Iceberg series as water damaged artifacts. We sold every single print at the auction. A ton of people came out to support me. I felt so blessed in that sense and lucky to have the friends I have.

A lot of my personal work starts with the premise of “the chosen road.” I’ve chosen this path and this is my journey. With what has been dealt to me, I’ve just got to deal with it. One minute everything is great, the next I’ve got nowhere to work. I’ve been through so many different emotions, from frustration to anger to upset. I’ve been a lot luckier than some, especially those who have been affected by the bushfires. You have to take stock of what is good in your life and focus on the positive things that could come out of it. Otherwise, it’ll just eat you up.

Water damaged prints by Simon Harsent that were auctioned.

Simon Harsent Recommends:

Read books

Look at art

Love

Forgive

Breathe