As told to Julian Brimmers, 3866 words.

Tags: Publishing, Editing, Writing, Design, Multi-tasking, Success, Collaboration, Education.

On how to generate new possibilities

Publisher and editor Alice Grandoit-Sutka discusses defining your social practice, making time for what you want to do, the value of print media, and learning through ritual and repetition.You’re a very multi-hyphenated person. What are some of your hyphens and entities, professions, and skills?

Uh, right back at me! [laughs]

Yes, that’s the first question you asked the person on the cover of Deem No. 1, adrienne maree brown.

I am a researcher, publisher, and host. Research has always been a way for me to create rituals for how to indulge in, nurture, and sustain a sense of wonder, but I also see myself as a researcher that synthesizes all of the “data” she is collecting by doing and making. Publishing is a very generous method to spatialize and share ideas, be it world views or sounds, across multi-media formats. Publishing also is a site by which I can help facilitate the creation of and also engage new publics, which is super juicy for me as a social practitioner! As a host, the research and publishing is embodied through the practice of hospitality, and seeing how to make folks feel welcome in a variety of contexts—food is a regular focus.

Over the past decade and a half, these skills have shape-shifted, but right now this description feels right. Over the summer I spoke to one of my oldest friends about each of these pursuits, and she said “Alice, you’re an intergalactic representative.” I have held on to this since she’s said it to me, as a reflection on the ability to communicate and move between the constellations of my practice.

“Intergalactic representative,” but born and raised in New York…

It’s weird to say like it’s something of the past. But, yes, I was born and raised in New York. I studied in New York, I lived in New York most of my life until I was in my late 20s. Since then I have planted some seeds in cities around the globe like LA, Berlin, Kyoto, and Copenhagen.

In these places, you have built different social practices for yourself. How do they help you communicate and interact with a place you have to make your new home?

I’ve been reflecting on this lately. I like to be in dialogue with and in connection to other species and cultural landscapes. It’s what helps me feel grounded to establish a sense of place. My first points of entry into a city are usually independently owned restaurants, magazine, and record shops. All of these spaces represent the flavors quite literally of the city through taste, sight, and sound. And these spaces become rich points of connectivity for others who might also share an appreciation for these flavors and rhythms.

Speaking of record shops, your first profession was in music, right? What was your training up to that point?

I studied liberal arts because of my interest in interdisciplinary experiences. The through line between all these things was anthropology. I was very much interested in cultural studies and engaging in training for how to be a good listener through conversational interviews, and how to read cities through cultural infrastructures. Music has always been a part of my life, and something I knew I wanted to pursue professionally. I have an older sister who works in the music industry, which exposed me to so many people and also pathways to explore the creative industries. I think the catalyst for me was a trip I took to London when I was 19. I had a chance to engage with the work of Amy Winehouse before her music was popular back home in the States. I was enamored with the music she was making and wanted to commit myself to working with musicians that made me feel like I did when I first heard Amy, but I also realized that I loved the research and pursuit of opening yourself up to listen to music from emerging talent, experiencing live music, and connecting communities. I was also very committed to A&Ring an Amy Winehouse album [laughs].

I was very aware of the “pay your dues” ethos of the industry, and so when I got back to New York, I applied for an internship at a major label that would inevitably distribute her record in the US. The stint at the label was enough for me to realize that I was very uninterested in the traditional ways of the music industry. I felt I had received A Tribe Called Quest’s advice quite clearly: the industry was shady and I had to design a way to participate in and contribute to the music space independent of a major label. I then had this awesome opportunity to work at a Black-owned, Harlem-based digital media agency, which was engaging with the industry in this powerful hybrid capacity: for sure leaning into digital formats like a record pool, an online blog, and also experiential. This framework inspired so much of how I would continue to cultivate an independent music practice for myself. I met some of my best friends and amazing collaborators during this time. One being Nu Goteh, who is my co-founder in DEEM.

Did any of your experiences in music proof applicable to you getting deeper into publishing?

I would say yes, because my experience in music took many different forms. It was very focused on artist management and development, organizing and programming showcases and festivals, and creating multi-media to communicate these endeavors. Those were formative experiences to the ways in which I practice design. Artist management, development, and A&R are beautiful practices where you establish the capacity to build intimacy with an artist. You’re tasked with firstly creating the conditions for them to feel safe and also bring out the parts of themselves they want to share through their art, as well as assisting in how they communicate with a myriad of audiences. It also allowed me to exercise unparalleled levels of empathy and care. I appreciated that a lot.

Working with extremely talented independent, oftentimes experimental, and emerging talent in a caretaking capacity helped me reconfigure my idea of what success looks like. In a way, all those practices are quite slow practices. It requires repetition and commitment, and at least the artists I was working with weren’t interested in instant gratification, nor was that the cards they were dealt. So that obscured timelines for success and also allowed for me to exercise and cultivate muscle in long term visionary capacities. I definitely feel like anything that I do, even in my current context, is always rooted in the skills that I wouldn’t have been able to cultivate anywhere else, had I not worked in music.

I feel like oftentimes cultural projects are a result of like-minded people trying to find an outlet for their collective interests. I was wondering if DEEM is also born out of the idea to have a common project with your friend Nu?

DEEM really is a baby of us having a creative studio together, which is called Room for Magic. I met Nu when I was working on a project with the digital media agency I mentioned earlier. We were little babies in our very early 20s who built a very strong friendship between New York and Boston, and various cities and jobs across the years. We had created the studio as a container for ourselves to actively practice and re-contextualize our relationship with work. Coming from professional experiences that existed at the intersections of arts and marketing, we wanted to move the work from being used to drive desirability about products and towards the thinking and insights that will help us create desirable futures. In that regard, starting our studio was a big deal. DEEM is a full-on extension of that.

Can you tell me a little bit about the general idea of DEEM as a design magazine? I’m asking because, contrary to many design magazines, DEEM seems to be dealing less with purely ornamental, style-driven ideas of design. There seems to be a deeper sense of mission and purpose.

I guess I would clarify that DEEM is a journal, long-form and full of wonder. DEEM is inspired by the dynamic experiences of our team, and committed to honoring the capacity for design to transform the way we live. But what we found is that design conversations tend to happen in silos and focused on aesthetics and output. It misses the opportunity to invest in the multitude of possibilities when we frame design as a diverse and process-oriented practice. We think of design as the steps through which something transforms with intention from imagination to manifestation, which is something anyone is capable of doing. If we frame it up this way and situate it within a larger community discourse, we can invite more people to participate in the urgent conversations of our time.

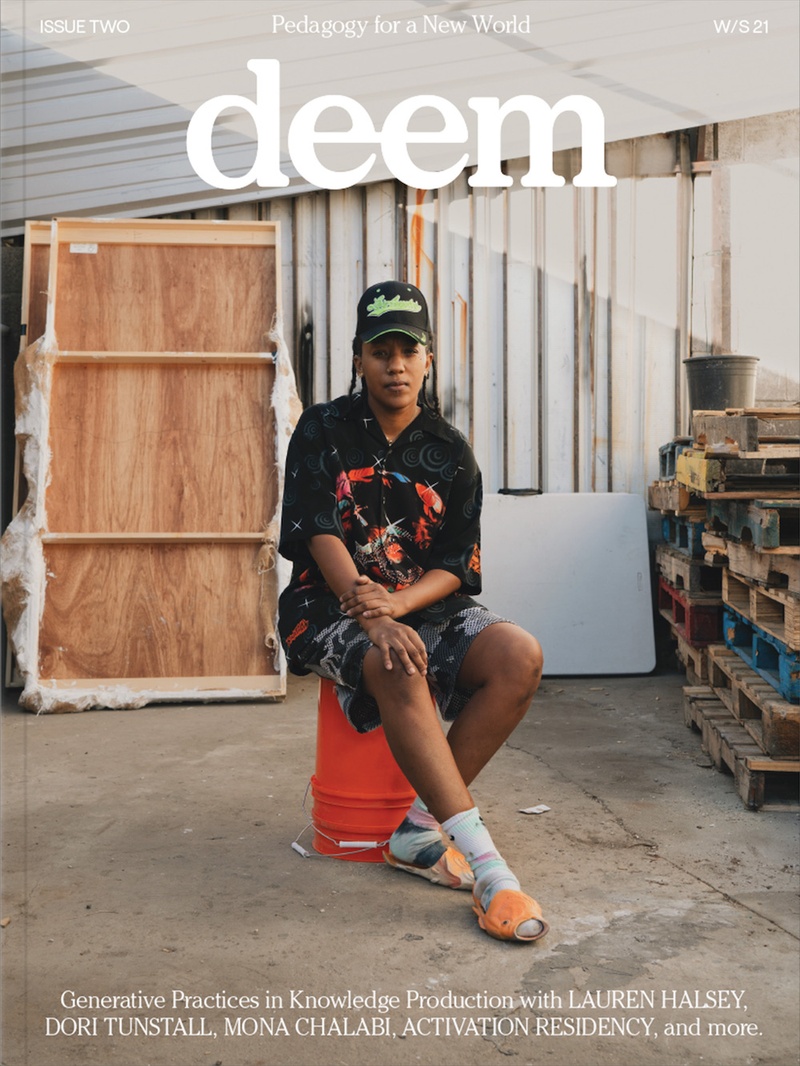

In order to streamline this broader approach to design, you’re creating different umbrellas for each edition. The second edition focuses on topics of education and educational institutions. Number one was about dignity, and the cover story was an interview with adrienne maree brown. You said that her concepts were instrumental for the ideas behind DEEM. Can you elaborate a little bit on that?

For each issue we set a condition we’re designing for. The foundational topic was dignity, and interrelationship with the quality of our lives. It felt important to us to center a new design discourse in the thoughts and words of a black woman, a design doer. We had to ask ourselves: who is committed to expansive and bold visions that can translate into the actions we need collectively to shape our worlds?

What’s beautiful about adrienne maree brown’s book, Emergent Strategy, is that it exists within a larger constellation of being, one that is very much representative of the way that she works. It’s her real time synthesis of many different thinkers, and peers, and concepts, and thus an amazing toolkit for how we could start thinking about our relationship to change. Prior to making DEEM, it was very apparent, from a socio-economic perspective, that certain structures and systems needed change. But that can be an overwhelming concept. I think what she was offering were small scale solutions for how we could start to actually practice this beyond trying to find one overarching solution.

One of the questions that she raises in the book is: What are the changes that we need to make in order to be, first and foremost, in better relationship with ourselves, and thus in better relationship with the planet? And then it all cycles upwards from there. For us, that was a beautiful point of reference to start from.

As for your own role, what kind of obstacles that you didn’t expect have you encountered while adapting to your new role as publisher?

Publishing has always allowed me to access the embodied knowledge I have acquired from the practice of arts organizing. Bringing together minds and hearts to articulate a collective point of view is fascinating and quite literally gives me life!

I would say the biggest obstacle has been the pandemic—surprise!—as it really changed the way we made DEEM. The first issue allowed us physical and intimate encounters for a good portion of the stories, as well as having the opportunity to visually document that moment in time. We are pretty much like any other publication, mostly facilitating conversations virtually now and relying on visual archival material from contributors to illustrate the stories.

We also have a distributed network of team members. We have been trying to balance the act of real time connection when immersed in the makings of a thing, and trying to account for how that translates when you’re working remotely.

Print is also a format that I enjoy because it forces one into the act of letting go and releasing the work into the world with no real way to make changes after the fact. But once something is in print, it’s no longer yours, you know what I mean? You become well-versed in accepting and loving imperfection. No matter how many brilliant editors and copywriters you collaborate with, we’re only humans, and making media that celebrates just that. There’s always going to be something you wish you caught, or changed, and accepting our humanity is a part of the process as well.

Also, some of the concepts that we are pursuing do feel very much rooted and informed by our lived experiences as Americans. So we’re actively trying to find and continue to open spaces for relatability. Everything about publishing is very relational, from finding the entry points for the conversation to commissioning. And you have to learn the art of surrender, like, are you really committed to a story? Sometimes it’s not going to happen on your arbitrary deadline, because the other person is also a human who has other real things happening in their lives. In this current climate that we’re in—and will be in for a while—we have to acknowledge that people are living, loving, but also suffering, scared, and fatigued. We’ve been living with this collective grief that we’re all trying to process and that means being gentle not only with ourselves but with others. To me that means honoring that, although we might be very excited to be in touch with someone, they are not alive to exclusively be doing interviews. If you are making something that involves the input of others on other people, you have to surrender to that, you know?

Another obstacle is making space for active reflection in a process. Research is everything. It quite literally transforms us through every single insight that we have the privilege of publishing. I also think making this space is essential to be able to apply the research to our own respective practices.

Speaking of natural timelines and individual needs, was it hard for you to assemble a team around this?

I think about bringing together teams as planting seeds. I don’t think it was hard to assemble a team, a handful of our teammates are friends we have worked with in different capacities in the past and also some newer friends who have found through the journal and feel connected to our mission. I love the range of experiences our team brings together—we are producers, poets, researchers, writers, archivists, illustrators, graphic designers, musicians, artists. We are still an independent publication and we do not have, for instance, 10 full time staff members that can dedicate all of their working hours for the week towards the project. But the vision keeps us communing and prioritizing time, in a way that feels good to everyone’s schedules.

One thing I noticed about DEEM is that it is very much situated in the now. How important is it for you to be rooted in questions and issues that directly affect people at the moment, more than just being of historical value, so to speak.

I want a practice that is both critical and generative. Sometimes we can invest a lot of energy critiquing what was, which can block or limit the potential to cultivate possibilities of what could be.

I don’t think we’re all aware of how ridiculous and flawed these existing systems are, so we should critique them. But if we do not actively make the space to generate new possibilities, we will still be stuck in this moment. And I do not like being stuck in a feeling that I do not sit well with. In terms of voice and stories for the magazine, the biggest focus is that a lot of social engagement happens throughout the process—from the organization of the research material, to the sacred acts of editing and producing each issue. And when it becomes a printed artifact, it takes a life cycle of itself, which I still do think is very much focused on this idea of engaging people around possibilities, existing or new.

The second edition of DEEM is a great example, because you’re discussing existing forms of education and what the educational sector could be. It reminded me of one episode of Steve McQeen’s mini series “Small Axe,” where they did a similar thing addressing how some British schools were specifically designed to keep a certain demographic less educated…

When I think about design, again, I’m not really so interested in objects, but in exactly these systems. The ways that those schools feel, look, and function are clearly products of design. They are intentionally underfunded and then made to exclude people or to put you in a pipeline that can literally inhibit your trajectory in life. Imagine, a program, literally designed to disengage you!

I often wonder, what if I had found teachers early on and consistently throughout my training that were invested in understanding how to engage me around certain subjects based on my strengths and interests? Instead I feel that many educational programs are very exclusive and inaccessible; they’re designed to just make you a worker at best. How we learn and generate our worldview is through educational experiences, most specifically through school. But a school is only one format of education, right? It’s not the only thing. And I think that people only associate education with school. That, too, becomes quite limiting. Because of the higher educational industrial complex in the U.S. you amass a significant amount of debt towards a degree, as if when you complete a program at university you suddenly have generated all the knowledge that you need in this life, and then learning just stops there. One of the biggest things we’re always trying to highlight is that learning is a life-long process. You know what I mean?

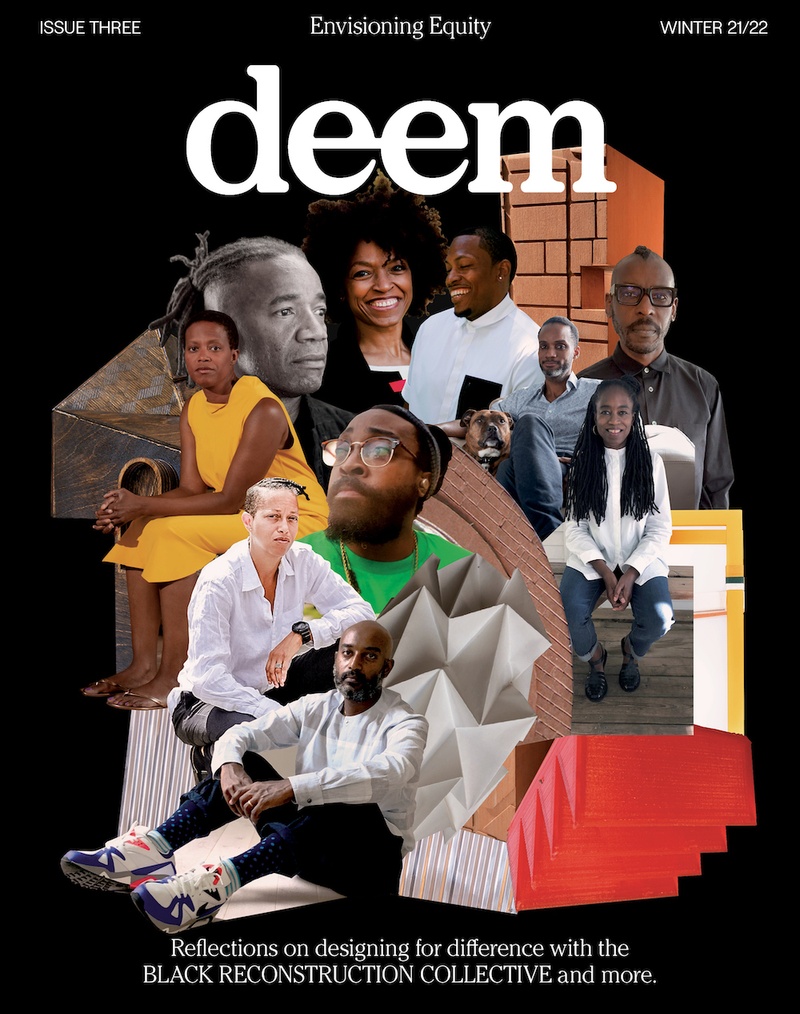

Can you already tell us a bit about what can be learned from DEEM Vol. 3?

Volume 3…I enjoy that we’re referring to them sequentially as you would a mixtape! It explores the concept of equity as a complex design challenge we seek to understand in order to reconstruct systems that affirm our humanity. Equity accounts for disadvantage, damage, and liability and ultimately our path forward relies on how we recognize and account for difference while also acknowledging our interdependence. There are so many beautiful insights on this topic from our generous contributors, and I think our cover story with Black Reconstruction Collective pulls us into a moment that is in progress.

The idea of building your own social practice is, for the most part, something that no one has asked you to do. Oftentimes it doesn’t bring in any money, it’s not necessarily part of the ecosystem of commerce. But it’s clearly an act of empowerment and a testament to your own interests. As someone who’s done that multiple times in your life, what would you advise a young person trying to find a meaningful outlet to put their energy into?

I am just always trying to find space to listen and to trust myself. Recently I said that I want to become a professional letter-of-resignation writer [laughs]. Other people have told me that I’m a valuable resource when you’re ready to make that change towards self-actualization, by helping build confidence to take those steps by putting language to that. I think I just really encourage people to make the time to listen to themselves, and then make the space to trust themselves. And sometimes, listening to yourself also could just mean listening better to the people around you that are reflections of you. For me, it’s always helpful to map out my constellation and make sure that I’m listening to each part of it. Because sometimes, if I feel like not sitting in silence and listening to myself, I’m listening to people that are reflections of me, or consult source material that is reflective of who I believe myself to be. It really kind of helps me generate that space for trust, to be able to make a change.

I guess, trust is really the key word here, because you really have to trust your interests, and that they’re worthy of being pursued, right?

Indeed. And there’s a lot of noise, so it’s a matter of making that a habitual practice. But it will get sharper over time, if I could promise one thing.

How do you make time to do all these things?

I used to be on a super default grind mode, I think sometimes that’s a rite of passage in New York. I think it’s creating and holding true to your own concept of and relationship to time. For me, I am trying to practice a relationship to time that sees it non-linearly, and also as an abundant resource. It’s an honest attempt to regulate and balance my nervous system by divesting from artificial timelines and capitalist urgency. The hardest part of it, though, is, after doing all that work to figure it out for yourself, then you have to convince others that are around you that this is the way in which you see it. Good luck with the second part. [laughs]

Alice Grandoit-Sutka Recommends:

Five food-stuffs that have changed me

La Baguette Haitian Patties on Linden Blvd in Cambria Heights NY (Little Haiti): The taste of my childhood, Haitian puffed pastry filled with the best savory fillings, something for everyone – stewed veggies (legume) amongst my favorites are cod, and smoked herring. Best eaten on Sunday mornings :) Locations throughout BK and Queens now!!

Chef Minh’s Porridge, LA: Chef Minh Phan’s specialty, highlighting the best of California cuisine, with a base of healing rice porridge using California farmed rice (Koda farms) and Chef Minh’s toppings that taught me so much about how to construct flavor.

Dani’s House of Pizza (Kew Gardens, NY): In my opinion New York’s best slice, always the last meal to send me off, and the first to welcome me home. I think it should be enjoyed as a mandatory two slice minimum meal featuring the classic slice with Dani’s legendary sweet, red sauce and the pesto slice. If you’re feeling mixy you can order an extra side of red sauce to adorn your pesto treat.

Tombo (Copenhagen) Shokado Bento: My partner has trained in Kaiseki Ryori, a hyper-seasonal multi-course meal native to Kyoto. I had the opportunity to eat this meal in Kyoto and cried many times over the rhythm of the service, the flavors, as well as the meticulously carefully prepared ingredients. The bento becomes a container to express a miniature version of this for a poetic, multi-sensory expression of the season.

Baroo Los Angeles (Friday lunch): Chef Kwang and Mina’s food will change your life, no matter the location or iteration, from strip mall to canteen in a swap meet. Order 1 of each category, for sure. Korean soul food that is equal parts experimental, nutritious, and affordable. The best time to go is right before the weekend rush for Friday lunch.