On holding onto your vision

Prelude

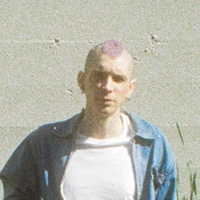

Tamara Jenkins is a screenwriter and director known best known for her intimate and darkly comedic films The Slums of Beverly Hills (1998), The Savages (2007), and Private Life (2018). Her creative output has also included acting and performance art. She lives in New York City.

Conversation

On holding onto your vision

Screenwriter and director Tamara Jenkins discusses making what you want to make, the difficulties of finding funding, and believing in what you do.

As told to Arianna Stern, 1976 words.

Tags: Film, Beginnings, Day jobs, Money, Success.

I have a question about getting things made. I’ve read in interviews that you’d have a script ready, you’d have actors in mind, you’d approach production companies, and they would be like, “No thank you.”

It depends. The Savages was really hard because it dealt with death. Even with those great actors, it was hard. I think it really was about, “Oh, in the first scene, the guy smears shit on the wall,” and it takes place in a nursing home. There was lots of things people don’t want to see.

To my knowledge, every one of your features has been a critical success and has had great actors in it. If you were a production company, wouldn’t you be like, “yes”?

In that case, that was very subject matter-related, but it was also before streaming, and there weren’t as many places to go make things that were more difficult, or whatever. It was like Fox Searchlight and it was Focus, and it was very small.

When I was trying to get Private Life made—which was also about something people don’t want to talk about, infertility—it was at one place, and then they ended up not making it. Because there was an explosion of different sources to go to, we wasted a year—it being done and trying to get it financed.

So, I don’t really know. I’m writing something now and hopefully I’ll find somebody to fund us. I really don’t know each time, because I don’t make movies fast enough. By the time I come out and look around, it’s a different planet. It’s like, I go underground, then I come up and I’m like, “Streaming? What’s that?” Hopefully, I’ll be done relatively soon, so it won’t be a dramatic shift. How many shifts like that could there be?

Like all of my films, I lost years trying to get it made. And then sometimes people are like, “Well, you don’t make that many movies,” which is true, but then it’s like, “Yeah, but it took me a really long time to get it made.” And it’s not like, the next day, I hand it in and then I’m casting and on set. It’s torture, generally. I don’t know if it’s that, necessarily, for everyone, but it’s hard. It’s hard to get things financed sometimes.

When you were just starting out, how did you support yourself?

As a film student, I was a waitress, I was an assistant to a woman on the Upper East Side, and I would do secretarial things and pay her bills—which, god knows I was the wrong person to do that job—and do personal errands. She wasn’t a famous person, she was just a person who needed help doing stuff.

Somewhere in there, I got some grants that saved my life at various points. In fact, at many points in my life when I thought it was over and I’ve applied for things, spitting in the wind thinking, “This is never going to happen,” I got all of this support from different places, one of which was the Guggenheim Foundation, one of which was New York Foundation for the Arts, and something called Art Matters. When I lived in New England, I got something from New England Foundation for the Arts. Anyway, I have been very lucky that when the chips were down, somehow the grant was granted, or the fellowship.

Even the Sundance Lab, it’s a fellowship to go there and work on your stuff. What’s the…? “I’ve relied on the kindness of strangers,” which is Blanche DuBois. In some way, I have relied on the kindness of arts institutions.

My older brother was always a very grant-oriented academic, so fellowships and grants and applying for things was in the air. I had a body of work that was expanding because, before I was a filmmaker, I was a performance artist, and I did lots of these performance pieces in Boston. Then I came to New York and I was performing them here, so I had this little growing body of work, and then transitioned into movies.

In terms of filmmaking style, the actors you work with always give these amazing performances. Is there any go-to conversation you have with your actors to get everyone on the same page?

I think that the casting is so essential. That’s the famous thing people say, “Directing is like casting,” because when you get the right people for the parts and also for each other, I feel like it almost is directing itself. I’ve never really had to translate to someone like, “This is a little bit more…” They pretty much go in there getting the feeling of the piece. There’s comedy inherent in the pieces, even though they’re often gloomy on the surface, and the comedy is coming out of a naturalism.

I appreciate what you’re asking, but it’s not like doing a Wes Anderson movie, where everybody’s going in there with a very clear presentational style. If you’re doing theater, it could be presentational or it could be really naturalistic, but I don’t think I’ve ever found myself needing to translate yet.

You’ve worked with these incredible people, including baby Natasha Lyonne. Her performance in The Slums of Beverly Hills really stood out to me.

Yeah, I feel really lucky. Now I’m writing a teenage character and I’m like, “Can’t Natasha shrink and go back in time?” It’s a little ensemble piece, it’s not as single protagonist-ish. She was nothing like anybody else. And when we were auditioning people, there was nobody like her. She didn’t seem like an actor.

The Slums of Beverly Hills is about a working-class Jewish family, which you never see on screen. I was wondering if putting working-class Jews in a film—and the contrast to what’s expected of a Jewish story—was on your mind when you were making it.

Jewish stories are always privileged people living in Beverly Hills in a different way. The socioeconomic aspect of their life was like—that’s why it’s called The Slums of Beverly Hills, because they were economically not supposed to be there. They slipped in under the fence. I’ve seen some people really, really connect to it and they seem to be people from a working-class Jewish world.

It’s like in television, if you see a working-class family or even Friends or something. How did they live in that space? It always makes me crazy. I remember going like, “How do they afford that space? What neighborhood is that?”

I always just take that part very seriously, like, “How did they get that?” Or, “Do they have one of those? How would they have that?” Anyway, I don’t think it was in the forefront of my mind to represent working-class Jews, but I am half-Jewish and the socioeconomic stuff was super important to me.

There’s so much I love about that movie. The dude energy—being a girl surrounded by all this dude energy is a very specific experience.

I have three brothers and when I grew up, my mother wasn’t around, so I was super isolated. When you’re alone with just men and boys, and all the stuff that you would maybe lean on a mother for, that character did not have. That’s interesting that you connected to that.

Is an interview an appropriate context to tell you a story?

Go ahead.

I was probably about 13 or 14. If I knew I was going to have my period on my dad’s weekend, I’d always bring pads and tampons from my mom’s house, because I did not want to ask my dad. And there was a time when I forgot it and I was like, “Ah, dad! I really tried not to do this!”

I totally identify with that. Is it different now, female shame? Is it the same? I don’t know.

I don’t know.

I have very disturbing memories of making Slums of Beverly Hills—an executive saying to me, “I have a note when Natasha goes into the bathroom and she’s peeing and we hear the pee, can we cut the sound of the pee?” And I was like, “Well, what would she be doing in there? She’s sitting down on the toilet and then she wipes herself.” And he was like, “Well, I even showed it to some of the secretaries and they felt the same way.”

I was like, “Girls pee. I don’t know what to tell you, sir.”

I bring that up, because it was such a different time to make anything that dealt with female bodily stuff, whatever year that movie was made. The idea that an executive was upset by the sound of a girl peeing is so crazy now, but then, it was a thing.

My story is from the early 2000s. Maybe now, 20 years later, our society has matured.

If you were a teenager now, would you still be like, “Dad, can I get…?” Maybe. Now I’m writing a teenage character, being a mother of a teenager as opposed to having a daughter head.

There’s a really beautiful thing that François Truffaut talked about. When he made Antoine Doinel and 400 Blows—it’s like he was Antoine Doinel or he was his brother. But then when he made—I don’t know which portrait film of the Antoine Doinel character—he was the father and then he was the grandfather. In those movies, Antoine Doinel’s growing up, but you’re looking at it from a different lens. It’s interesting.

I had a writing teacher in college who said that having a child is something that permanently changes your point of view as a writer, because it changes your identity. So up until that point, you’re somebody’s child and then you’re somebody’s parent.

Yeah, it’s a pretty weird shift. And it’s not even just the parent of your child. I think that your understanding of the whole world shifts somehow, the relationship to community. Your kid’s in school and you just open up, the self goes away a little bit. The tyranny of just me, me, me, me starts drifting away. Not completely, but the self sort-of goes away.

You become enmeshed with the school and the neighborhood and other kids. You look at other kids like they’re sort-of yours, too.

Tamara Jenkins Recommends:

This One Summer. It’s a graphic novel and I love it so much. It’s two girls that only see each other on summer holiday, and it’s some weird little resort—but not a fancy resort—where all these cabins are. There’s a lot of feeling to the art, and it’s just a gorgeous book. It’s about female friendship and family and adolescent loneliness, and there’s some tension with the parents. It’s like the way a song, you could dip back into it and get in a mood, you could just dip back into the book and get the feeling from the images like, “Ooh yeah, that place.”

The 400 Blows. Because we were just talking about it.

Annie Baker. I love her. She wrote a play called The Flick that is just so fantastic.

Dried figs. I love dried figs. I usually have some around.

Uniball pens. Generally I like Uniball pens, but lately I’m doubting. I’m just wondering if there’s another pen out there to love. It’s nice to fall in love with a pen. These Uniball pens, they run smooth on a page in a way that a lot of pens don’t.

Franny and Zooey. I love this book, as everybody does. It’s another thing that you can just dip into and get into the mood of it. And also it’s very funny and there’s a lot of cynicism and warmth.

- Name

- Tamara Jenkins

- Vocation

- screenwriter, director, performance artist

Some Things

Pagination