On risking everything to follow your dreams

Prelude

Yalda Mousavinia is a co-founder of Space Cooperative, an organization that’s currently working to create a decentralized space agency called Space Decentral. Space Decentral is focused on developing projects that both improve life on Earth and evolve humans into a spacefaring species. Prior to Space Cooperative, Yalda was a Senior Product Manager at Oracle. Her career as a product manager and designer for web platforms spans over ten years. She earned her Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering from UC Berkeley, and holds an Astronautical Engineering Certificate from UCLA.

Editor’s note: This interview is part of a series leading up to the 2018 edition of Rhizome’s Seven on Seven.

Conversation

On risking everything to follow your dreams

An interview with designer and Space Cooperative co-founder Yalda Mousavinia

As told to Willa Köerner, 2811 words.

Tags: Technology, Beginnings, Collaboration, Inspiration, Money, Anxiety, Business.

How do you define the work you do with Space Cooperative?

We launched Space Cooperative about a year and a half ago in an effort create a network where people can come together to crowdsource and crowdfund space missions. The idea was that there are a lot of people who have a lot of different ideas for large-scale space projects, but if we were able to consolidate our minds, perhaps we could actually execute on them in ways that haven’t been tried before. That’s how Space Cooperative came about, and that’s why it’s now morphing into this platform called Space Decentral.

In terms of my own work with Space Cooperative, I wear a variety of hats. I’ve been the user experience/product designer of the network, as well as the system architect. I’ve also connected people to form the company, and I’ve been doing a lot of the writing for the white paper. So yeah, a variety of hats, whether it’s helping with the overall organization, planning events, or just plotting out the road map and tasks. It’s kind of like the CEO-type role, but we don’t use titles like that, especially because as we grow, we want a lot of people to share those leadership roles. But so far I’ve been the one that has the time to really dive deep on it.

How did you know it was time to move on from your previous job and cofound Space Cooperative?

For a few years I was thinking a lot about space, but it was never clear to me when I would make a transition in my career. In 2016, I went to this NASA Space Apps hackathon, and that’s when I started to meet different people, and to explore different ideas around building applications for space. In Los Angeles they also had a certificate program for astronautical engineering at UCLA. After that hackathon, I just decided to make a life change. When I left Oracle, I thought my reason for leaving was that I wanted to finish these courses, start studying for the GRE, and apply to graduate school to get a master’s in space systems engineering.

But then a few months went by. I’d quit my job, and was starting to study. At that point, I went to this conference, the International Astronautical Congress, which was in Mexico. While I was there, it just became apparent to me that this one idea that had been in my mind for a while was something I needed to explore. The idea involved building a collaboration platform. At that point it wasn’t just about space—it was about creating a digital utopia, like trying to create this social network-like environment through which we could all work together to improve Earth.

That idea has existed within me ever since I read the book, From Counterculture to Cyberculture, by Fred Turner. That’s when this idea of a social network for good, or for developing a collective purpose, started to seed within me. And then in 2016, I started to think about this idea in the context of space. After going to the conference, these two ideas started to merge—like okay, it’s not just about going to outer space, it’s also about using space technology to benefit planet Earth.

And then I just realized that developing that idea was my purpose. I realized that I didn’t have to go to graduate school—suddenly, I already knew what I need to do. That’s when we decided to form Space Cooperative. Some people that I’d met at the hackathon earlier in the year, along with some people from the certificate program at UCLA, were the initial founding team.

How did you figure out how to set up the collaborative Space Cooperative structure? It feels very Aquarian-Age cooperative.

During this phase where we only had the founding team, we still didn’t have a name for the company and we were still brainstorming. We were like, “Oh, do we want to do a non-profit cooperative?” For me, personally, I’d always been fascinated with worker ownership and worker autonomy, so that started to become my personal preference for how the business should be structured. And when we searched for a name, it was like, “Oh, there is no Space Cooperative already?” It just seemed to really fit with the message, and with what we were trying to do.

Working in Silicon Valley, and working for different corporations over the past 10 years, I’ve realized how it can feel like you’re putting in a lot of work and effort, and yet your thoughts and opinions aren’t being heard. So part of our cooperative structure was a reaction to that—how can we actually ensure that the future is not just controlled by the people who have a lot of wealth? How do we build a future where the people at the lower levels—the people who are actually building the technology—are not automated out of their jobs?

So really, the cooperative structure aligned ideologically, and it seemed like the best way to make the whole organization more transparent. Also, with this approach, if someone new joins, you don’t have to think through, “Oh, what’s your equity going to be?” The math around it is so much more transparent. A cooperative is essentially just all about the time that you put in, so you can bootstrap an organization with sweat equity and just have everyone be at the same level in the beginning. It just seemed very empowering.

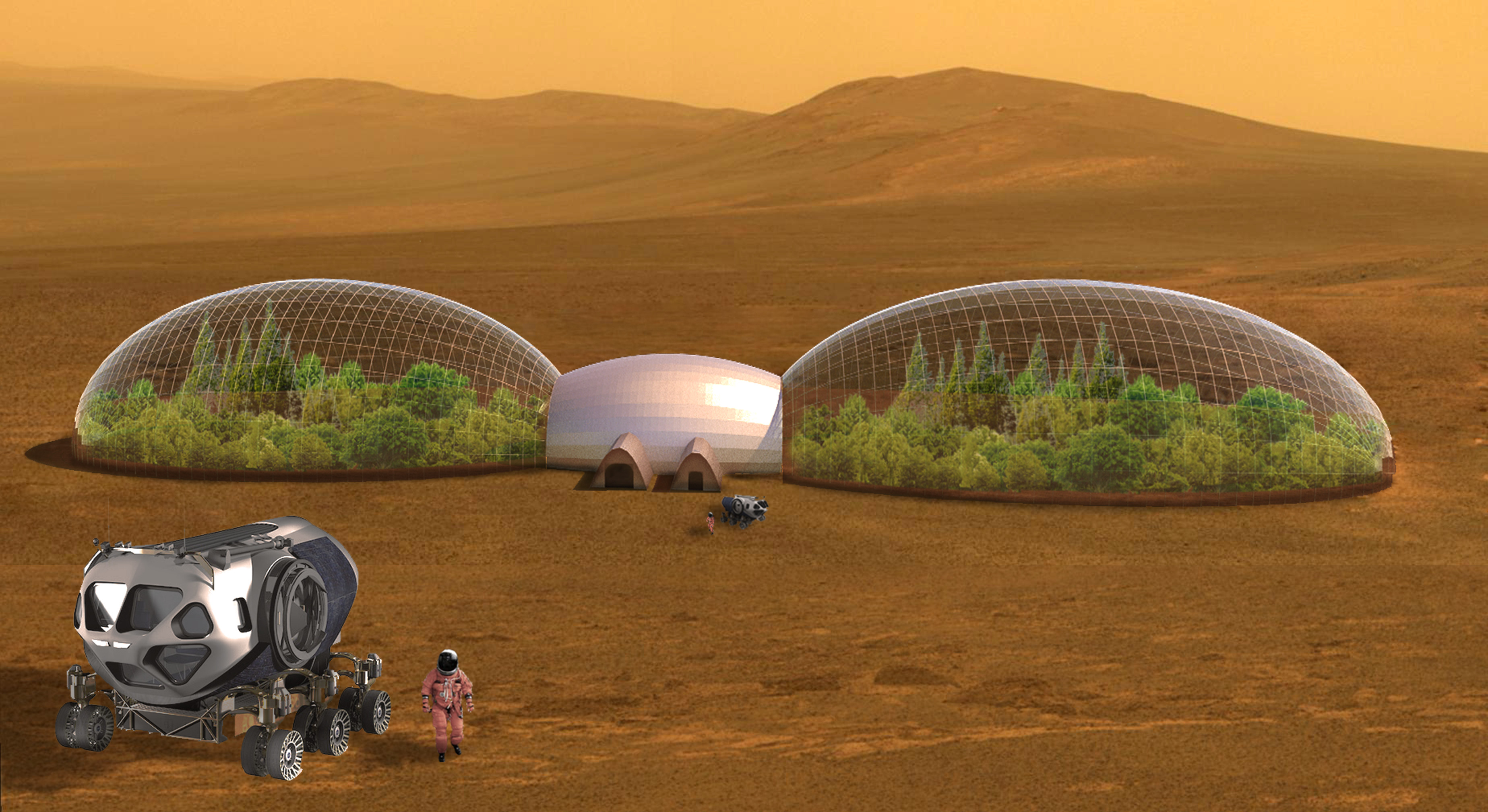

Concept for a Martian Agriculture Mission

A lot of people—like people who are forming startups—don’t think about the cooperative structure. This is because it’s not an easy way to raise funding right away, as VCs don’t really understand it fully. So yeah, it does have its challenges as far as getting off the ground and having a full-time workforce that’s getting paid. Figuring out how to make it successful has been a slow process.

What have you learned about the nature of collaboration through all of this? Has it required you to unlearn certain behaviors born out of hierarchical, bureaucratic, and patriarchal structures?

Yeah, we’ve definitely all had to learn to be better communicators about why we feel certain ways about different decisions. We use this tool right now called Loomio for collective decision-making. It would probably be really hard to practice collective decision making without having a tool that easily lets you vote, propose, agree, and disagree on things.

Despite having this governance system, there have definitely still been disagreements. Sometimes I might feel very strongly about things, and I’ve had to learn how to vocalize my feelings at those times. It’s like, “Okay, here’s my viewpoint. Do you understand this? Why or why not?” It’s not as easy or as comfortable as having a traditional organization, but after you go through these arguments and discussions and you get through it, you’re like, “Oh, wow, this actually feels amazing.” It feels amazing to hear someone else’s point of view and then to actually have them change your mind, you know? It can feel stressful for some people, but after you get through it, you adapt. You realize that this is actually a more humanizing way of collaborating and working together.

What have been the hardest parts of getting Space Cooperative and Space Decentral off the ground? What kinds of obstacles did you encounter and how did you overcome them?

The hardest part has been the length of time it’s taken to get this far, and how much longer it will take to reach some real funding milestones. Recently, we won a grant from an organization called Aragon to build a planning app on top of their ecosystem. So about 18 months after we started, we’ve finally raised enough funding to pay for a team to develop this tool. It’s not enough to fund Space Decentral fully, but it was finally like, “Oh, wow, we reached this milestone.”

I think one thing we should have done differently is talk to more investors early on, even though we were a cooperative. We were trying to be perfectionists about the platform and the features, but if a lot of people are just putting in time on the weekends, you can’t grow that fast. So yeah, we just should have started asking for money sooner. At this point, it’s really about finding financial contributors that want to help accelerate the mission and the vision.

What has the learning curve been like for dealing with projects that are space-related? It just seems like such an ambitious scale to work at. Working on projects that involve literal rocket science and grants that have to be in the millions of dollars in order to do anything must be a little overwhelming.

I’ve realized that there actually is a lot of money in the world. I’ve also become more comfortable with the idea that, “Hey, large-scale projects can be possible. Large-scale projects can be funded.” We just don’t really have all of the tools for the accountability or for the directing of the money towards the organizations that are going to develop the technology or the accountability. I start to think in that sense of, “Okay, a lot of people have done large missions like this before and a lot of people know how to do it. Yes, it does cost a lot of money, but compared to how much money we collectively spend on things like clothing, it’s really not that crazy.”

I’ve never personally worked on a multi-million-dollar space mission in my life, since this space path is also new to me. But there are so many different aspects of aerospace engineering or space-mission engineering that one can decide to focus on, and each of those paths has its own learning curve. A space mission is just like a giant production project that requires many different experts to pull off. One person is not going to be required to become an expert in all of those areas—it’s really about figuring out what that focus is for each person, right?

Architectural Concept for Space Cooperative’s Headquarters

For me, the thing that I decided to focus on was creating this network that can connect all these experts who are needed, so we can do this at a scale that hasn’t been attempted before. So that’s taking my 10 years of experience in product management and UX design to construct this network that can connect all the people who already have this expertise, in order to help get us there faster, but to also help educate the ones that do want to learn.

Once this network is built, I still actually have to figure out, “Okay, what aspect of this project should I work on now?” As of this point, I’m not sure if I would actually be working on a space mission, as opposed to architecting this system of how people can connect and work on missions together. That’s just been what my career path has been in general—architecting a system as opposed to working on the space mission itself.

What have been some of the biggest “Aha” moments you’ve had along the way?

I guess that’s the “aha” moment that I have a lot while working with people from the cooperative. Like I said, you have these debates, and then the debate is worked out, and then you’re just like, “I love my company. I’m so glad I did this.” I can’t imagine doing anything else, because I’m growing and learning so much along the way. I’m learning how to be a better person in so many ways, you know? How to be a better communicator, how to be a better listener.

If you think you want to do something in life and you keep coming back to it—if it’s a recurring idea or thought that keeps coming up—then just change your life and do it. I think back to that a lot. I’m so glad that I listened to myself, and actually made the decision to change my life around and do this. I feel like this is what I’m supposed to be doing. I get afraid about what I’d do if this ever came to an end, because it feels like this is my dream work right now.

If you really want to start something, you need to have that drive. So listen to yourself. I’m glad that I listened to myself because to me, doing this feels right. Even if it feels hard sometimes, you have to know that going after your dreams is not really something that’s supposed to be easy.

I’ve had a lot of sleepless nights. I’ve had a lot of days of just being so overwhelmed that I can’t stop crying and breaking down. There’ve been a lot of ups and downs, but at the end of it, I’m okay. I’ve just become accepting of that fact that I’m going to be stressed out, I’m not going to be able to sleep, and I’m going to worry a lot. But I push through it.

The other thing I was thinking of was how before our grant came through, I was literally on my last dollars. I was asking a friend to loan me money. I was behind on rent. But at just the right moment, this grant came through. And it was just like, “Whoa.” It’s weird the way that things work out sometimes. If you just keep pushing for it—keep figuring out how you can make it work—you’ll realize that your brain starts to do weird things. You are able to connect the dots.

I’ve also realized that even if for some reason I have to go and get a normal job somewhere, there’s no reason that Space Decentral or Space Cooperate would have to end. We intentionally designed it in such a way that it can just exist regardless of having full-time employees working on it. There’s no reason to be afraid as long as we make sure that we’re building this thing that can thrive and survive without us leading it. It’s also important to sometimes stop and remind myself, “Okay, why did I do this?” You don’t need to be afraid. Everything is an opportunity.

For people who are at that point in their lives where they have this idea and they know they need to pursue it, but maybe they’re afraid or they just don’t know how to do it… what advice do you have for those people?

I would say to just try and save enough money so you’re able to at least survive for about a year. And if you don’t have enough money, if you have someone that you can live with in their guest room, or if your mom or your dad or your family are around, just quit your job and do it. Figure out how you can allow yourself to work full-time on your idea, whether that’s starting to do more freelance work or just spending your savings. Or spending your 401(k) if you have money in that, or selling stocks. I would just say to do it. Just risk it. If you don’t risk things—if you don’t put your own money in or make some sacrifices—then it’ll be impossible to ever know if that idea will work out or not. But if you really want it, if you’re really passionate about it, you just have to get outside of your comfort zone. You have to do it.

I mean, it’s not for everyone, but once you surrender to it, you start to really feel okay. It doesn’t matter anymore that you’re spending all your money. Of course it’s easier if you don’t have kids or a husband or a wife or something like that. I mean, it’s harder advice to give to someone that does have a family that they need to financially take care of. But if you don’t have that, then just don’t worry about buying that house. Just spend your money.

Yalda Mousavinia recommends:

-

Surveillance Self-Defense: Tips, Tools and How-tos for Safer Online Communications, by the Electronic Frontier Foundation

-

From Counterculture to Cyberculture by Fred Turner

-

The Last Question by Isaac Asimov

-

Inventing the Future by Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams

-

Try to develop as much open source work as possible and support open source projects

-

Use the app Signal instead of texting, WhatsApp, Telegram and Facebook

- Name

- Yalda Mousavinia

- Vocation

- Designer, Product Manager, Co-Founder

Some Things

Pagination