On finding freedom through constraints

Prelude

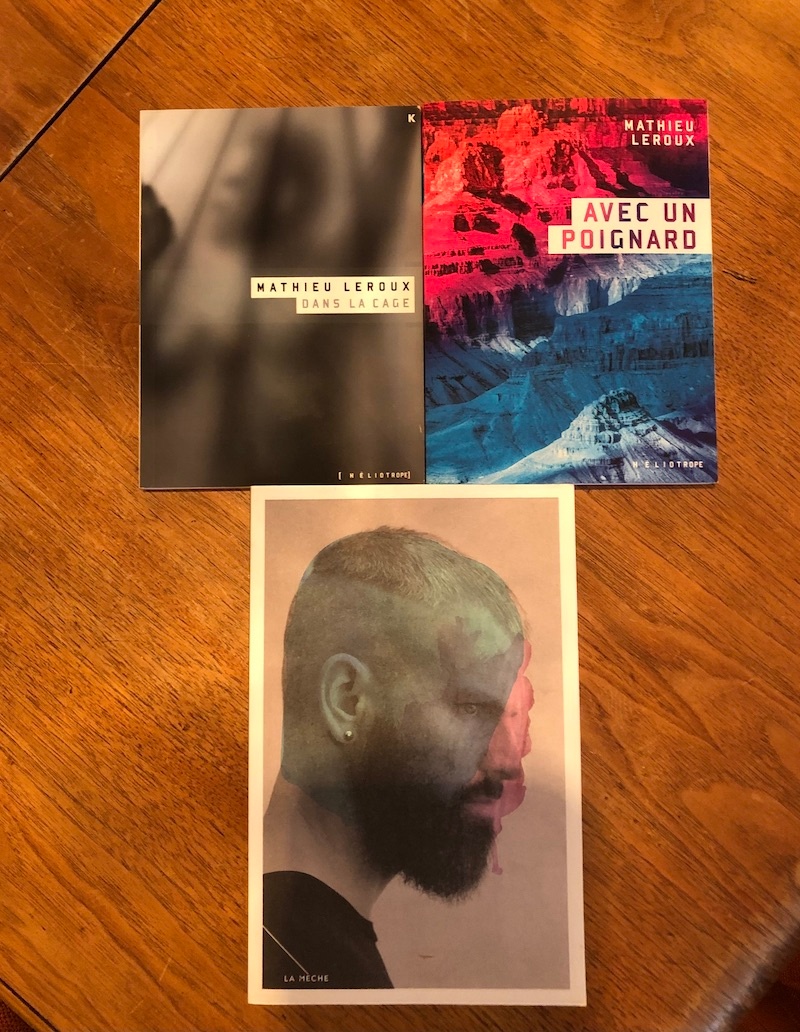

Writer, theatre director, actor, dancer, and dance dramaturge, Mathieu Leroux co-founded the theatre collective, Les Néos, writing and performing 100 short plays in five years, while also serving as the artistic director. He has acted as dramaturge on the tanzmainz production Twist for Mainz’s Staatstheater and on Vancouver Ballet BC’s Relic. In 2021, he created and performed the dance duet Bones & Wires with Sébastien Provencher. He has built sustainable partnerships with prominent choreographers and has been working with, amongst others, Victor Quijada, Dorotea Saykaly, Helen Simard, and Alexandra Spicey Landé for many years. His first novel, Dans la cage, was published by Héliotrope and his short plays accompanying an essay on performing the self, ”Quelque chose en moi choisit le coup de poing,” can be found at La Mèche. His newest novel, Camouflé dans la chair, was published in September 2023.

Conversation

On finding freedom through constraints

Dramaturg, writer, theatre director and dancer Mathieu Leroux discusses the value of structure, discovering art as a child, asking for the rules so you can break them, and removing layers to expose what is already there.

As told to Grashina Gabelmann, 2027 words.

Tags: Theater, Writing, Dance, Multi-tasking, Process, Focus, Inspiration.

What is your creative practice?

I’m lucky enough to work in three different fields that people like to separate but I think they feed into each other: I work in dance mostly as a dramaturg, I work in theater as a performer and director, and I work in literature as a writer. And I go back and forth. So a lot of the work is witnessing what people are making and trying to contribute, to the best of my capacity, to their vision. There is still a lot of theatre performing—what I’m originally trained in—which also involves observing/working as part of a team. And then I do my little solo thing with the novel writing.

How did you originally connect to performing and to dance? Are there any memories from being younger?

I come from a family that’s undereducated. No one has a diploma. This is very specific to the economical context of the ’70s, ’80s in Quebec. My mom raised us alone on a very meager salary in the ‘80s. She discovered quickly that I loved reading and was more the artsy type: she would pile books on my night table and I was reading them all. And then, in the last two years of high school, I tried theater.

I was a very shy and awkward kid without many friends; I was still shy during theatre classes but I had found my tribe and something in me unlocked. Around that time I saw a big play and it made me understand the term “directing.” The play was based on a book I had read so obviously I pictured it a certain way in my head, and then I saw the production and I was blown away. I was like, “Oh, okay, I just got what directing a play means.” And that shook me to my core. I thought, “I want to be part of this. I want to be part of theatre making.” I did a pre-university degree in Literature, and then I went to theatre school which is where danced showed up in my life.

Bones & Wires with Sébastien Provencher (Wilder Dance Building), April 2022, ©MNPilon

Oh wow, you were exposed to so many different disciplines from an early age. What happened after you graduated?

I got hired by a puppetry company. I toured with them for seven years, as I was starting a contemporary theater company with three other graduates. After a few years, I was tired of touring and puppeteering. I needed something else. I joined an art collective and that’s where I really blossomed : my writing skills got stronger and I re-connected to something I had forgotten. After seven years of that—magic number for me, I guess—I needed a break from the collective work and the democratic system of art making in a big group.

You needed a project of your own.

Exactly. And that’s when I went to do my Masters in Literature. I was always convinced that I was chronically stupid and not smart enough to pursue a research project. I think the Masters was mostly to prove to myself that I was able to go through an extensive intellectual process, and that I could find my working method because I’m a very organized and structured person. At the end of the degree I had two manuscripts ready to be published—an essay, and the first novel. Then I returned to theatre/live arts and I worked with two choreographers who both were clear that my title on their piece was “dramaturg.” And then everything fell into place.

What exactly is a dramaturg?

For me, a dramaturg is the choreographer’s main channel. A mentor of mine told me when I was younger that the dramaturg is like the memory of the process. I think that’s one of the elements.

The dramaturg goes through the entire process, from the first conversation with the maker until the end, and will keep tabs on everything that has been discussed and tried. I also think a dramaturg has to be a bit of a detective because you shut the fuck up most of the time and you observe what’s happening in the studio. And that means observing the dancers: what are the power dynamics in the studio, who gets along with who, who is loud and taking space, and who is more quiet and needs more guidance or intimate feedback? Who has slept with who, who shouldn’t work together.

You facilitate conversations between people; you help the choreographer find words for their thoughts. I think you have to be very good with historical knowledge regarding the craft, whether it’s theater or dance, so you know who made what when. You need to be curious and enjoy research; you need to fuel the process with texts, images, videos, esthetics, historical references, etc. You need to remember that you are there to push someone else’s vision, and not your own. You also have to remember that your job is to feed clarity, meaning, intent.

In the end, I think the core of the job is: remembering what is being built, knowing the foundation, and being aware what goes and shouldn’t go into the piece that is being made.

Mathieu Leroux’s first books

You’re just about to finish another novel. You mentioned you love structure and it’s important for your work as a dramaturg. How does loving structure and your skill for bringing things together come into play as the you who writes?

It takes me a long time to actually write a first draft because I need six months of research before jumping into it. A lot of people think it’s fluff, and that artists don’t do much when they’re like, “Oh, yeah, I’m researching” but that time is important. I’m very inspired by visual art, so there’ll be a lot of visual references, even though it’s about writing, reading, going to exhibitions, digging into media archives, etc. I watch a load of documentaries as well—documantries that are related to what I’m working on.

I probably read around 15/20 essays for every book I work on (and novels that touch on similar subjects). Out of those 20 books, there’s always a solid six that are more substantial. And out of those six, a lot of notes emerge. I transfer all notes in one document, and I classify notes by themes. When I am writing, I might come upon an idea but feel stuck : I can return to these notes, which open up new pathways for me. Out of those six books, there’s always two that remains on top, and I call them my dialogue partners—meaning they’re always by my side while I write. And if I feel a sense of being lost, I refer to those two. So there’s a lot of information to retrieve—which helps me build the structure of the book—in those six months of research.

Before I write even one word, once all of that information is in my brain, a title usually appears. And when the title appears, it means I’m ready. Then I build a full structure, the approximate length, which helps me be super precise about the breath the book will have. If I know it’s a 115 page book, I know it’s a very short breath, a kind of punchy text. What I like in writing is finding the proper concept. I don’t want my books to be super intellectual or concept oriented; if the concept is not visible at the end, good, but it’s still a driving force for me.

So concept, title, length/breath, and then slowly I’ll see the main events appearing in the structure, plus I always know how the book ends before I start writing. This allows me to follow whatever pathways that appear while I’m writing—and they can be many—without losing my way.

I don’t feel the infamous writer’s block—I don’t, because it takes such a long time to get to the writing, and everything is so well prepped before doing so.

Writing, to me feels, like taking a block of concrete while having an image in mind: the piece is not super clear yet, but as you chisel at it, the piece reveals itself. It was already in the block of concrete. You just didn’t know it was there. I feel the same with writing or theatre and dance making: I think the piece already exists. It’s up to you to find ways to reveal it.

On stage in Les Chiens by French novelist Hervé Guibert at the Cinémathèque, Dec 2021, ©BG

It’s there rather than you are the one creating it?

Yeah, and I find this idea super exciting. The research has been done so thoroughly, so it definitely exists. And then it’s just a matter of removing layers to expose what is already there.

Fascinating. I don’t think I’ve ever spoken to a writer who can describe their process in such detail. I was smiling to myself while listening to you speak thinking that this level of structure is kind of insane and also amazing and it works so well for you.

I know I sound like a nutcase. I’m not going to lie, it’s laborious during the building of it. And I’m often like, “Why do I do this to myself?” But I love it. It’s like a Tetris game, and it’s about trusting that the work, the reading, and the structure building are a good process, that it allows you to be free. I do believe that constraints allow me a lot of freedom.

I actually hate it when a magazines give me a carte blanche. I’m like, “That’s not how my brain works; do you have a theme, is there a length related to it?” And then they’re like, “Oh, well, I guess we have this through line of loss in our project.” Cool. Then it’s a piece about loss. Do you want it to be narrative based or more poetic? How crazy can I be with the form? Can I play with the actual structure of the text or does it have to be linear? All of a sudden people have a bunch of answers for you and you’re like: “So it’s not carte blanche.” I like rules, but I also very much like cheating. So give me the rules: What are we working with? What size is the box? And then I’ll see what I can push and stretch in that box, and remove what I don’t like.

I can really relate to your work process, and I do a lot of research and collecting stuff and before I start writing it feels like jumping off a cliff. It takes me quite a while to get that point. And sometimes I feel a bit like OCD about it or sometimes I’m like, well, am I doing that because I don’t trust myself and I need all of this security to do it. But, looking at it less negatively, it’s all part of the work.

I could research endlessly, but I have a timeline. I need to stick to it so that I don’t get lost in “I’m in a research phase”—and then I don’t know where I’m going. I think structuring has a bad rep: people think it makes work too heady. I don’t believe that. I often get told that my writing is raw and emotional. Structure and research allow me to open up and go deep because I know why I’m pushing those buttons, or what I’m releasing into the work.

Mathieu Leroux Recommends:

Montreal electro sensation Carlos Mendoza

Montreal Interdisciplinary Dance Company Other Animals

South Korean DJ and record producer based in Germany Peggy Gou

Gay Bar: Why We Went Out, by Jeremy Atherton Lin

Most Books written by Maggie Nelson, Catherine Mavrikakis, Bret Easton Ellis, and Simon Girard

- Name

- Mathieu Leroux

- Vocation

- dramaturg, writer, theatre director, dancer

Some Things

Pagination