On learning about yourself through making work

Prelude

Chiffon Thomas (b. 1991) was born in Chicago, IL and holds an MFA from Yale University and a BFA from The School of The Art Institute of Chicago. Thomas has since developed a multifaceted practice incorporating embroidery, collage, drawing, and sculpture to explore the self as split, fractured, and transforming. Thomas has completed prominent residencies with the Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Skowhegan, ME and the Fountainhead Residency, Miami, FL. His work is included in the permanent collections of the Pérez Art Museum, Miami, FL and the Currier Museum of Art, Manchester, NH.

Conversation

On learning about yourself through making work

Visual artist Chiffon Thomas discusses spending time with people’s stories, slowing down, asking for help, the importance of observation, and working through failed experiments.

As told to Annie Bielski, 2740 words.

Tags: Art, Photography, Process, Inspiration, Collaboration, Education, Time management.

One aspect of your work is your use of family photos as source material. You render subjects and interior scenes in embroidery and paint. I’m thinking about the quickness of the snapshot and the slowness of embroidery. You’re really sitting with small parts of the image for a long time and paying attention.

What I’ve been finding out about images that I capture and images that are pre-existing from photo albums and shot in film cameras is that they have a different quality to them. Just seeing the way that a person outside myself composes a moment that they value, or feel to be honorable to capture or to canonize like that—I’m trying to understand what was actually occurring during that time period, especially because they’re from my past and some of them were from before I was even alive. It’s interesting to see what kind of environments these subjects, my family, lived within, and seeing how they made a living through minimal amounts of resources or money. It’s interesting to see how they create domestic settings and love and tenderness in these spaces that I might not ever fully have access to. I do have my memories with these individuals and it’s nice to project myself into past time periods and be reflective, not only just about the moment but what that person’s psyche was. I’m always questioning what was going on with these family relationships and how they were being mended and how they were being created. I really love photographs that I didn’t take, that have some history to them. I think about this, too, “Is it selfish of me to focus so much on my own family history and my lineage?,” and it’s like, “No,” because there’s so many gaps and there’s so many pieces that will never be answered. I only have so much time in this life to excavate as much information as I can. As family members are passing away around me, so much of that [information] is getting lost in people that I never met. I would like to at least archive something, or keep something in this world to pass along so that there’s not more gaps created.

Case, 2020. Embroidery floss, thread, found tree bark, acrylic ink, chalk pastel, rebar wire. 35 x 23.5 x 1.5 inches

The archiving information and mending relationships elements you mentioned feel related to the nature of embroidering on cloth, preserving and repairing what is.

I think even the stitch line, that individual mark-making—I could relate it to painting but it’s something different where you’re actually building out these individualized marks. It could be really fragmented or you could have loose areas with it and I think you could put more of a meaning behind how the tension works between these marks I carry through. The stitching, too—it’s just such a slow pace. It slows me down.

How do you approach something you don’t know how to do?

Oh, my goodness, it’s such a challenge. Even now, when I am embroidering and things are really large scaled—that was a shift for me, because I like to work really intimately. I like to have things that are portable and I can carry and pull out in the car or on a train ride. I started to enlarge the scale of my work when I was applying to grad school. [It was a challenge] figuring out how to create flesh and line directionality and instill the truth to this textile representation of these subjects that are figurative. It was really difficult for me to find ways to shift that stitch in that material but still hold true to this painting quality, and have these techniques of painting still in them

I do a lot of tests. I have a lot of failed experiments, I have money that I put into things that don’t necessarily become anything, things I destroy by accident. I will create an image that I’m not happy with or create an object that I’m not happy with and out of destroying it and then rearranging it, I’m able to make something that I am satisfied with, more so than the original product. I think that’s how I approach things that are challenging, just being able to detach from them. I have to detach from them to be able to even be innovative in any way—not that I’m trying to be the originator of anything, it’s just when you get to that point where something is challenging, how do you ever get over that obstacle? You have to be willing to take a risk. I destroy and then I reconfigure a lot of things. I try not to be wasteful with things that I have messed up or think that I’ve created an error in. I try to find a way to recycle it back into something else, like a project at a later time that I think it would fit better in, because there’s a reason why it wasn’t working with whatever original idea I had. It’s not totally wasteful, especially if I’ve been trying to build things that are more structural, not just making pictorial work. I’m trying to actually build themes and settings that [the pictorial works] live within by using parts from demolished homes. That has been extremely difficult because at a certain point you do need an engineer or an architect to be able to make those things safe.

I’m noticing that I’m having to bring other voices in who are experienced, where it’s not just me being isolated in the studio by myself anymore. It’s like you have to get to a point where you are able to ask for help from other people who have knowledge. I find it’s hard for me to ask people for help sometimes because I always think people will have their own thing going on, but people enjoy offering their assistance in things that they are good at. It’s nice to have them challenge themselves or explore. I needed to build a room in my studio because I was using plaster when I was at Yale. I would carve into the plaster so there would be a lot of particles in the air just all the time and they never settled, really. When they would settle, they would settle on everything. There would just be plaster everywhere. I was like, “I need to contain this plaster in a space where it can just live in this one space.” Me and my friend José Chavez built this room in my studio over the summer and he ended up using that project for his application to grad school because he wanted to study environmental architecture. I had no idea he was going to take that opportunity and apply it to something that will propel him forward in his career.

Lacerated Faith, 2020. Black Pigment, paint, chalk pastels, bible books. 9 x 12 x 17 inches.

Do you ever feel stuck, and what do you do to move through it?

I do feel stuck, especially when I’m reaching the end of a body of work. Sometimes my natural default is to re-incorporate hand embroidery as much as I can. I got to a point where I was like, “You know what? No. There are so many different ways to approach art.” If I want to make a video and I have this idea that just will not function in this medium then I have to change it. Again, I have to ask for help, or I’ll ask what software people are using. Along with just trying to read things that I enjoy and listen to interviews and Art21’s, I use search engines. Google is a super resource. Sometimes it’s just a word that I’m thinking about that I don’t necessarily have an idea of what it may look like. I will just literally Google it and see what kind of images come up that I’m inspired by. That’s really helpful, because, what does a subconscious look like? What would come up if you Googled that? What have other people thought or pondered on? That’s me getting help again. I use as much assistance as I can.

I was watching this H.R. Giger documentary—the guy that created the drawings for the Alien sagas—it was just on his process as an artist and developing that creature. He just fused all of these different aesthetics from all of these things that he thought were interesting and he enjoyed. The documentary was like, “He didn’t just steal from anybody, he stole from everybody.” I thought that was so transparent. It’s like, yeah, we look at each other. I look at what others are doing and I’m inspired by those things and then I’m able to generate my own interpretations of these things through inspiration of other people and other materials they might be using. So, I don’t see it as stealing. I just see that as “it’s all related” and that’s just how we relate and that’s how we understand the world around us, through each other. You create your identity through others. Even when you try not to, that’s how you are as soon as you’re born.

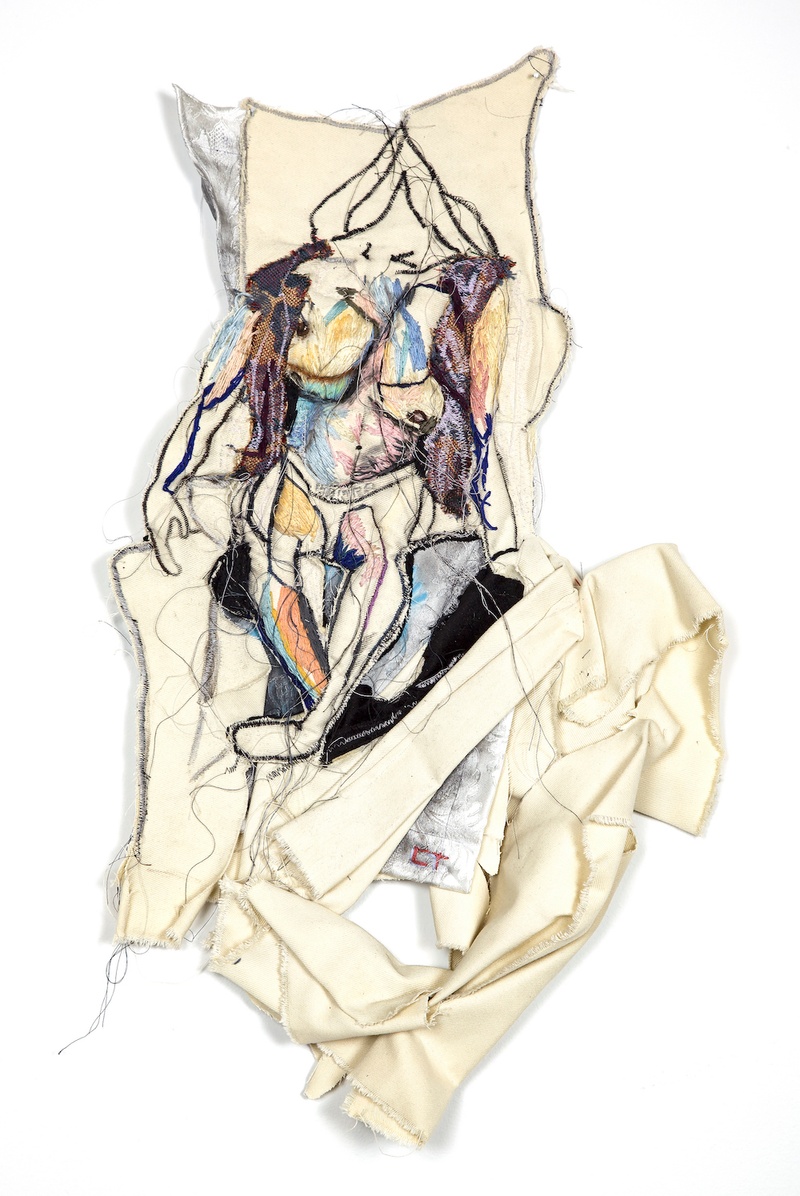

Precarity of A Person, 2020. Fabric, chalk pastel, embroidery floss and thread. 28 1/2 x 17 inches.

What’s your relationship to play?

I have to really make moments of play. I have to just let things happen that are humorous in my work because I’m too hard on myself. I know this. My work focuses on the past and other people’s psychological conditions and I’m trying to take them really seriously, so I’m trying to see the humanness in them all the time and sometimes it’s hard for me to find moments of laughter or joy in some of these family members’ stories because they have a lot of melancholy in them. It’s like I want to respect that and take them seriously but also represent them in this way that honors them. When I’m talking about sexuality and gender and racial oppression and those things, they’re really hard to sit with and they do take a toll on me after a while, so I have to do other things. I have to play my drum because it’s my only escape. I have to do something with my body that’s other than just being in the studio because I take that very seriously.

I was having an interview where somebody asked me what I was reading, and it’s only been within the past year that I’ve ever explored fiction. We started talking about how even through reading we find that there has to be this certain level of rigor, right? It can’t just be imaginative and fun or not real. That’s not fair. Our minds are so expansive, why is it that I only have to indulge in something that’s factual? Or [thinking about] when the two worlds collide—imagination comes from realism to a certain degree. It takes the two opposing things for that to even happen. I really consumed a lot of Octavia Butler this year. I’m bringing that up because I am just so fascinated by the way that she could build worlds and people and I’m just like, “She’s crafting a language and I could create a visual from those ideas.” I can see them. It makes them exist in a world. So, that’s been fun. I’ve never been a big reader and I would always be hard on myself about that, but it was because [I was reading] things that I wasn’t enjoying.

Do you keep a set schedule in your studio?

I’m really bad at setting a schedule because I like to work throughout the entire day. I don’t really have a set schedule but I do go in there every day and I am in there for a good 12 hours a day. Usually I’m there till around 1:00 or 2:00 AM, sometimes 3:00, and I start pretty late in the day, sometimes around 12:00 PM. Some days I wake up and I start, and some days I’m so frozen or intimidated to do the next thing that I’m in there not doing anything for two to three hours. I didn’t intend to do that, it’s just when it comes to destroying something or detaching from something, sometimes it takes me a while to even get into that motion. If something isn’t working, I know that’s the next step and it’s like, “Man. I already know what I got to do to this thing.” I don’t really like the nine-to-five type of stuff. I don’t want it to mimic a job. I feel like I’m looking for something, I can’t just relay that to a schedule like a nine-to-five.

Iron Father, 2020. Tree Bark, embroidery floss, fabric, window blinds, chalk pastel, rebar wire. 23 x 21 x 3 inches.

You taught art in Chicago Public Schools for a few years. What would you offer to younger artists or your younger self?

I would say know that there’s a career in art and that you can be an artist. You may not be successful for years, decades, but if you can make time to do it at any degree—try to just keep a practice going. I would definitely explain to them that you don’t have to be this A+ student—not that you shouldn’t challenge yourself or you shouldn’t have achievements or expectations or aspirations, but you can also be really good at what you are good at. See, that’s another thing. Sometimes people don’t know what they’re good at. Once you find something that just really comes naturally to you, really try to explore that. Whether it’s guiding people, whether it’s life-coaching, fitness. Things that come effortlessly to you, you should really hone in on and see what possibilities you can make from that. What I would tell a young person is, “Everybody’s good at something. Something. There’s something you’re good at. Try to really investigate it.”

What have you learned through making your work?

My work has taught me so much. It’s a long list. It taught me how to be open-minded, it taught me how to be expressive. It taught me how to speak up for myself and how to be compassionate and empathetic towards other people, because you have to spend time with people’s stories. Maybe that’s because these are the people that are close to me, I don’t know, but it also makes me look at the world differently because I have to look up things. What was I looking up? The psychology of splitting and having to code-switch, double consciousness, and different roles individuals have expectations to play. Gender roles. It has taught me a lot about colonialism. I probably would have fallen into these subjects later in life. I don’t want to say I don’t come from a family of readers, but because I was so deeply involved in having a studio practice and wanting to be educated, I continued to go to school and be around other people from different [backgrounds]. It was so diverse, and I was learning about their experiences and cultures along with knowledge that they had. It broadened my world so much and so rapidly that I wish I could have had some of those things earlier on in my life, and been able to share some of those things with my family, to really get an understanding of why the world is the way that it is. [It has taught me] to slow down, just observe. Just really observe. I don’t know, I feel like a totally different person.

Chiffon Thomas Recommends:

HBCU Marching Bands and Drumlines video footage. It’s so soulful, groovy, and creative.

Memory: The Origins of Alien (2019)

An idea I tell myself is: “Stay authentic in the work. You can be vulnerable there.”

Artists: Odilon Redon, Nancy Grossman

- Name

- Chiffon Thomas

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination