On what you can learn through moments of frustration

Prelude

Erika Ranee received her MFA/painting from UC/Berkeley. Her work has been exhibited widely in New York at the Bronx Museum, The Last Brucennial, The Parlour Bushwick, BravinLee Programs, M. David Co., Storefront Ten Eyck, FiveMyles, TSA Gallery, David & Schweitzer Contemporary, MAW Gallery, and at the Southampton Arts Center. In early 2019 her work was featured in a solo show at Lesley Heller Gallery. Later in 2019 her work was on view in a group exhibition at Wild Palms in Dusseldorf, Germany, and in a solo show at Freight+Volume. She was in a two-person show at Gold/scopophilia in Montclair, NJ with fellow artist Meg Lipke in 2020. She works in New York.

Conversation

On what you can learn through moments of frustration

Visual artist Erika Ranee discusses revisiting and reviving older work, having focus in isolation, how friends can help you know a piece is done, the stress that can surface after finishing a project, and letting a painting be free.

As told to Annie Bielski, 3101 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Inspiration, Beginnings, Creative anxiety.

Your paintings and drawings are influenced by the city, interior space, and the natural world. You’ve been working primarily from your apartment during the past several months of the pandemic. Has the shift in your physical environment shown up in your work?

The internal space observations are even more intensified I’d say, because we’re stuck here for longer periods of time, which I’m well adjusted for, because I like being isolated. It gives me time and freedom to think and focus on the work. I think that’s inherent for most artists. We work long hours by ourselves, and you have to be able to deal with that kind of focus in isolation, so it wasn’t a huge transition for me.

I started doing works on paper for the first time ever in 2016, and I was doing those works at home. I enjoyed having a different workspace from the studio space. Also, the smaller works are more mental, more psychological, so it really is conducive to that smaller space. I also have the television or the radio on, and I’m listening to people talking. I’ll know a movie audibly rather than visually, from the experience of working on the paper pieces. I’ve said this before, but I love listening to the British murder mysteries, and just figuring out the stories. I’ll look at a particular work on paper and I’ll know what part of the story has happened in that paper painting. The same thing happens for my paintings in the studio, the larger works. When I’m listening to music, I’ll see the DNA from a Jimi Hendrix album in there. I’d say that my work always dealt with internal spaces, bodily spaces—even the larger works—but now, it’s more intense. I like where it’s going. I think there’s more work, actually, that’s going into building the layers. There’s just this intense focus that wasn’t in the earlier works pre-COVID.

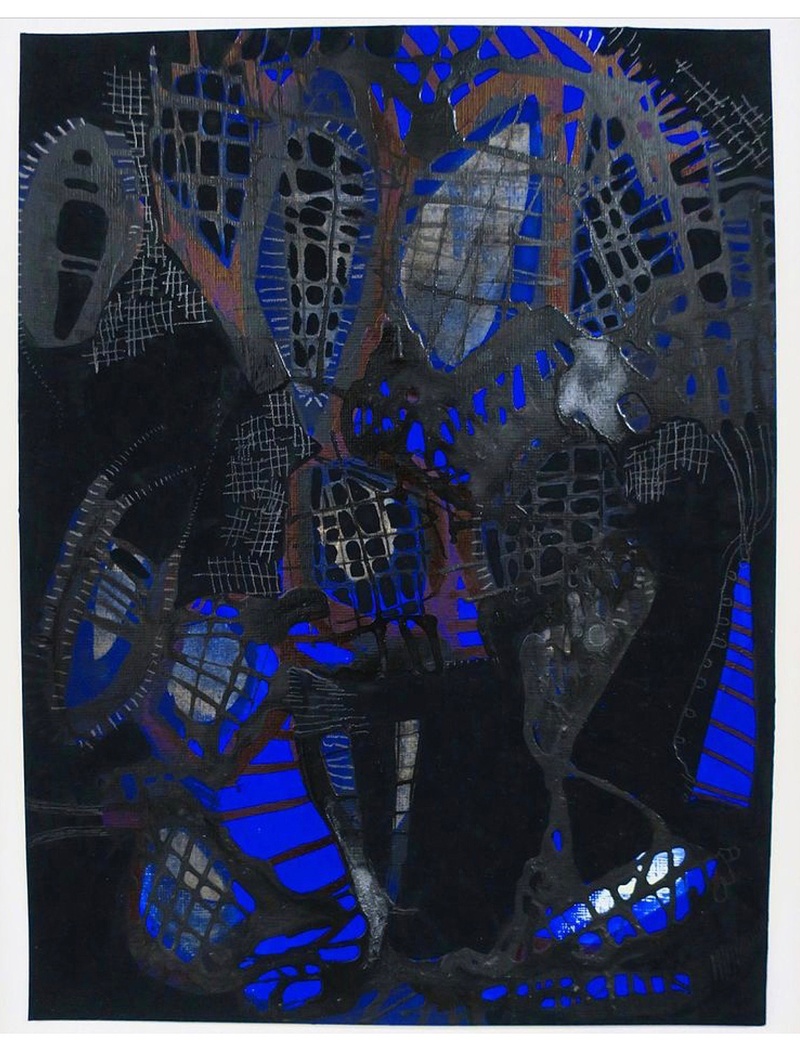

Fucked Up Flowers, 2018. Flashe, ink, and gouache on paper. 12 x 9 inches.

You just touched on the ways in which a painting can be like a time capsule, and I’m interested in the way you work. Do you find you come back to pieces after years?

Yeah, that’s exactly what it is. Recently I’ve been finding older works, because I’ve been wanting to see what the older works are saying to me. Some I haven’t even documented, which I’ve started to do just because I need to get organized, but I’ll go back into these older pieces, because I’m realizing, “This wasn’t finished. This has good bones and I can build on this story. There’s so much good stuff in there.” I don’t like to plan a painting anymore. I like to keep it open, so even when I start a painting, I’ll just use whatever leftover paint is hanging around that’s about to dry out, and I’ll just pour it onto the canvases. So, there might be a randomness to the color choices as I’m beginning this journey on the painting.

I was just looking at some old notes I made about this infomercial I’d seen, this evangelical program where this white guy is saying, “Look, buy this little square piece of green felt and you might inherit millions of dollars, or this private jet could be yours,” and it was just this little, square, green piece of felt, and he’s showing footage of these Black people. I thought, “Oh my god, he’s totally preying on these lower-income people, and a particular race of people, and he’s the leader.” The white guy is saying, “Look, buy this. Buy this thing, and you will be rich and happy.” So, I went out and bought some green felt and I’m going to add that into some of the paintings. I’ll just build my paintings like that. Whatever I come across will just get thrown in there. It’s not so much a narrative—it could just be all the things that I do or see in a day, or a week, or month. When I go back into those older paintings, I can find a place in those paintings where I can add that new stuff that I’ve come across. That’s how I work. I want to keep it free.

My earlier works were, as I say, locked in a narrative and I was doing extensive research, but the research was getting in the way of my painting process. I felt like I had to keep looking at that narrative and building that narrative and I couldn’t make that brushstroke I wanted to because, spatially, it might be taking out the forms, the figures that I was incorporating. Now, I can do all that stuff. I can just go nuts on a painting. I do start to edit as I end the painting. I’ll add flat areas to the wilder, brushy pours, because I do like structure. I do find that I need both there—the wild, free marks, but also a little control in there.

Do you ever feel like you’ve “overdone it?” How do you rein it in?

I’m always amazed when I see artists who throw away their canvases, or just cut them up, because none of my paintings are ever going to get chucked. I’ll just see it as, “This looks terrible. There’s so much stuff on here. I hate it, but I can always revive it. I’ll use it somehow. This will be a very thick painting.” I can’t kill a painting, I just find another way to revive it.

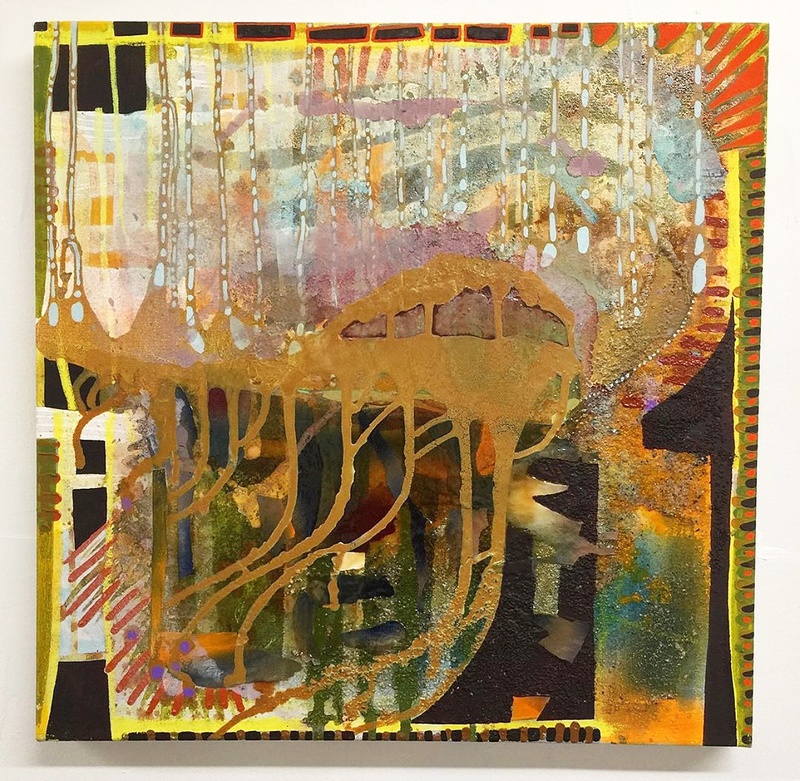

Alhambra, 2019. Acrylic, shellac, sand, spray paint, oil stick and paper collage on canvas. 24 x 24 inches.

Have you ever felt longing for earlier versions of work?

You know, there are times, especially now when the topical issues are so heightened politically, socio-politically. Back in grad school, we were all commenting on things that were very prevalent around race, and that’s from the ’90s. A lot of Black artists were making work around Black stereotypes. I did like the energy, thought, and passion around all of that. I’ll think about it, but it just doesn’t fit into my work in the same way as it did back then, but it’s something that I admire in the work of other artists right now who are able to really approach that commentary so poignantly. I feel like, “Okay, I’m just the lady over here making splashes and sprays.” But I do feel that it’s in the work. It’s in there for me, it’s just not obvious to see, because I’m also reacting emotionally from things that I experience or read, and it’s going to go in the work, whether I realize it or not. It’s just a different way of commenting. I think my former professor, Jack Whitten, was the one who actually helped to clarify that for abstract artists. His work is very political. You don’t always see it obviously in there, but it’s in there. His thought process applied to his work process in the paint. That helped me to deal with how I was approaching my work, and changing it from being figurative and narrative to this freeform, abstract painting style.

I appreciate learning more about your older work and how you think about abstraction. I initially thought of my question in relation to earlier versions of a single painting. Have you ever seen an earlier in progress image of one of your paintings and thought, “Ugh, it was fresh. What did I do?”

Oh, yeah. Just the past few days, I’ve been freeing up space on all my devices, and I looked at a couple of early photos I took of paintings. I’m like, “Oh my gosh. It was so beautiful. What did I do? Why?” At the time, I was just unsure. I mean, I even posted an early image of a painting on my Instagram and so many people loved it. This one artist who I’ve been interested in getting to know just fell in love with the piece and sent the image to all these dealers. I’m like, “Oh my god. I’m sorry, that’s dead. I went into it and I killed that image.” It was a big regret, but I learned from that, because then I was like, “I need to be free like that. I like those moves I made.” So, I’m applying that to the new work. In fact, I’m trying to get that painting back to that moment right now. That happens quite a bit. I have to be careful, but it’s hard when you have a lot of looming deadlines, because then you’re like, “Oh god, but I have to get this done. I don’t have time to look at it and step away from it, and breathe away from it.” That’s when you can start to overwork, because you’re just like, “I just need to get this to look like something that can show.” Sometimes you need an intervention from a friend who’s like, “Stop. Just stop it.” So, I’ll do that now. I’ll send images to friends who I think have a pretty good eye for what I’m doing, just [for them] to tell me, “Cut it out.” I’m still really bad about knowing when something’s done.

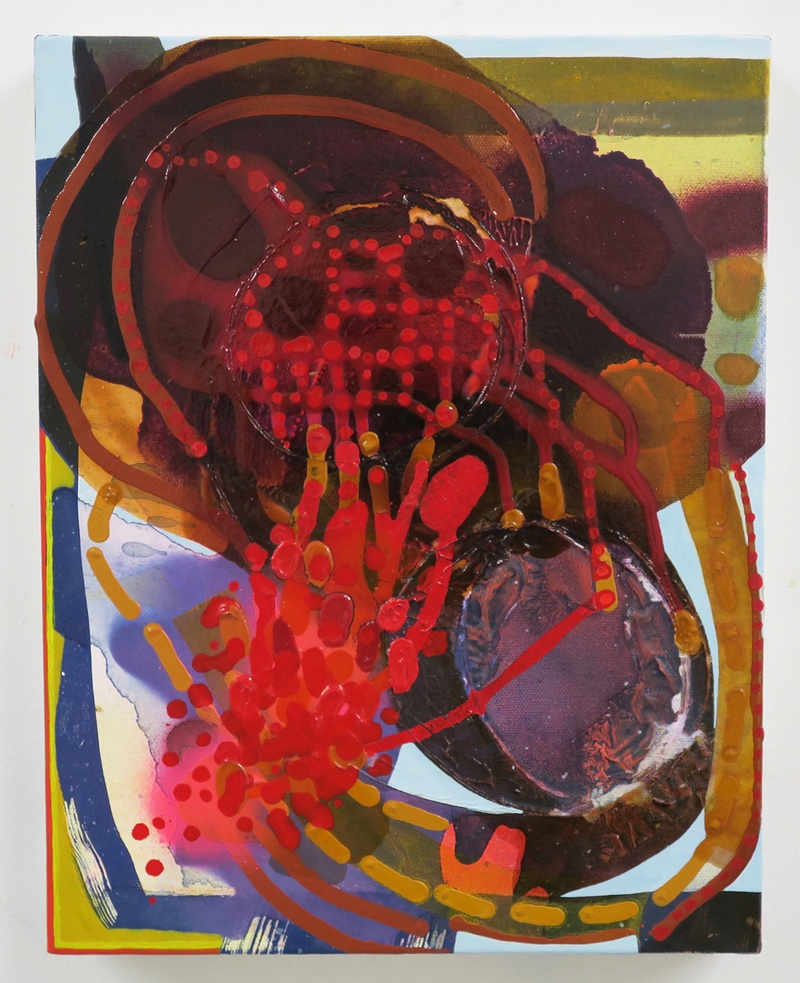

Rock Eater, 2019. Acrylic, shellac, and spray paint on canvas. 14 x 11 inches.

It’s common for creative people to experience feelings of anxiety, fear, or self-doubt at some stage of making or sharing their work. How do you work through those feelings when they come up for you?

The last solo I had, I made like 28 pieces in a short amount of time, and there was so much stress leading up to the end. One of the paintings I actually drove to the gallery myself, because it was still drying and I still didn’t know which way to hang it. I mean, I drove them crazy. When it was done, I was like, “Oh my god, that is such a weight off my shoulders now.” Then, I was looking at it again, and said “Oh my god, they all look terrible. It’s not good enough. I’m freaking out,” but I was so happy it was done and I didn’t have any more work to do. Then I entered this post-show funk and was like, “Ugh, empty. Don’t know what’s going on. Nothing’s happening with my work. It’s terrible,” and no one could tell me otherwise. I just felt slow and tired. I posted something about it, and so many people said, “Oh, that’s normal. Post-show funk is a normal thing,” and I didn’t know this. I had no idea.

I think when you work on something, they really are your babies. It’s like you put your heart and soul and everything into these pieces, and then at some point, you have to say goodbye to them. You have to figure out, “Did I care for you enough? I mean, is anyone going to like you?” Things that I would imagine you’d feel about something you love, something that you’ve made. I think it’s a norm. I call my friends who aren’t artists civilians, and I don’t think they understand what I’m going through. I think they think that I’m just sitting around in my studio having a party, drinking, and having friends over. They don’t know the full process here, and that it’s a profession, not a hobby, and that there’s a lot of serious mental work going on here.

At the end of the day, you’re hoping that something will sell, that someone will want to live with what you’ve created. That’s not a guarantee, so it’s a strange profession. It should just remain a hobby, really. Just make stuff without all the other worry, and it would be pure. That’s the challenge, too. You want to keep it pure, while in the back of your mind you’re like, “I just hope this sells so I can pay the rent, or I don’t have to have another full-time job.”

What is a good day in your studio?

I love the beginning, because I don’t know what’s happening, I don’t know how things are going to work out, and I’ve got a good music track going that I can just zone out on for hours. I like to just start with fresh, loose, energetic marks. I’d say I work about three to four hours a day in the beginning, then towards the end, the longer hours come to play because I’m fine-tuning stuff, tweaking stuff, details—all that. In the middle is when I start cursing and wanting to punch things, and I don’t know where the painting is going to go. It’s like a puzzle. I’ve got to figure out the puzzle and how to create these spaces. So, middle to end can be stressful.

There’s one painting that’s on the cover of the catalog for my solo show last November and every time I see this painting, it looks like an upbeat painting, but one breakthrough moment happened when I was so mad at it. I had been doing hours of tweaking and I was like, “It’s just not there.” I had this paper towel full of white paint and I just threw it at the painting. I’m like, “I’m finished with you,” and that turned out to be a great little moment. The next day, I was like, “Ooh, I like this,” and I left it in there. People always ask me about it. Sometimes that can be a good moment in the studio—when you’re mad at something and you think you can’t fix it, and then you do at that last desperate moment of aggravation.

That was a spontaneous moment, but do you have any go-to tricks you try when something isn’t working with a painting?

If I’m stuck on something or I’m feeling too precious about something, I will force myself to pour some paint on it or spray it, or shellac over it and then leave and come back the next day and see what happens. I have to do it. It has to be very impulsive. I can’t sit and think, “Well, should I put a little bit of this over here?” I have to do it fast before I have time to talk myself out of it. Honestly, I feel that I’m a controlling creative person, a perfectionist. I need everything to be just right. So, I think my whole art practice is about breaking away from that tendency. People might look at my paintings and think, “You’re a perfectionist?” I’d say 80% of my paintings are all about chance. Trying to create chance and getting rid of the comfort moments, and then it comes back in. Like I said, toward the end I’ll tweak things. I will be very particular about my sponge brush line being just perfect, and I can spend a good hour or two trying to perfect the line. I guess I just need that neurotic moment in my life. That’s an emotion I need to add to all the other emotions going on in the painting.

The Chorus, 2018. Mixed media on canvas. 24 x 24 inches.

What has been most surprising about your creative path?

I’m just amazed that I still can come up with new, fresh images. I’m happy that I made the switch from the figurative work to this work, and I can see that I’m still growing. I mean, I’m 55 years old, and I’ve been at this since I graduated from college, and I’m still growing. I love that, and I love seeing it in other people’s work, too, when they just keep at it and something happens. The work starts to change, and maybe they even go through some rough spots and you’re like, “Oh, what are they doing now?” But then you see they’re going through it, and they come out of it with this really strong work, and then success follows that. I love that trajectory. It’s hopeful to me. I saw that happen with Chris Ofili, but he started off successful, and then he went away to the island [of Trinidad]. He was starting to do this work that just came out kind of awkward, and the art industry just hated it. They were going after him about this terrible work. I thought it was refreshing, because it stepped away from his comfort zone, his success zone. He was like, “I’m just going to try this stuff, and I’m going to show it,” and then, he worked through that and then came out of it stronger, and of course now, he’s like a superstar. He’s one of my favorite painters. I love seeing stuff like that, and that, to me, is a surprise. It’s a gradual surprise for me, but I love that.

I was a government major in college, so I didn’t know I was going to be an artist. I was always creative as a kid. I was more craft-centric. I didn’t know how to paint anything until after I graduated college. My senior year in college at Wesleyan, I took a painting class at Parsons in Paris. That’s when I was like, “I like this. I like this medium and I want to make paintings and stretch things.” Then I decided to go to SVA after graduating from Wesleyan, and that’s when I took my first painting class, so I was like 22. I feel like I’m still learning. I didn’t really take too many painting classes. I really only had one, so I didn’t have too much schooling in that, so I had to play catch-up when I went to grad school. Still playing catch-up. Still learning. That’s exciting for me. I need to be stimulated like that. I’d be bored if I had to make the same painting.

Erika Ranee Recommends:

Artist Frank Bowling = experimentation pours

Artist Alan Shields = craft/bohemia

Gee’s Bend Artists = form

Natural occurring erosions and formations: Mushikui (Japanese word for worm eaten plants, or wormholes), woodpecker markings, and Cordyceps fungus.

Black eyed peas = current collage element for my smaller paintings.

- Name

- Erika Ranee

- Vocation

- Artist

Some Things

Pagination