On recycling ideas in your work

Prelude

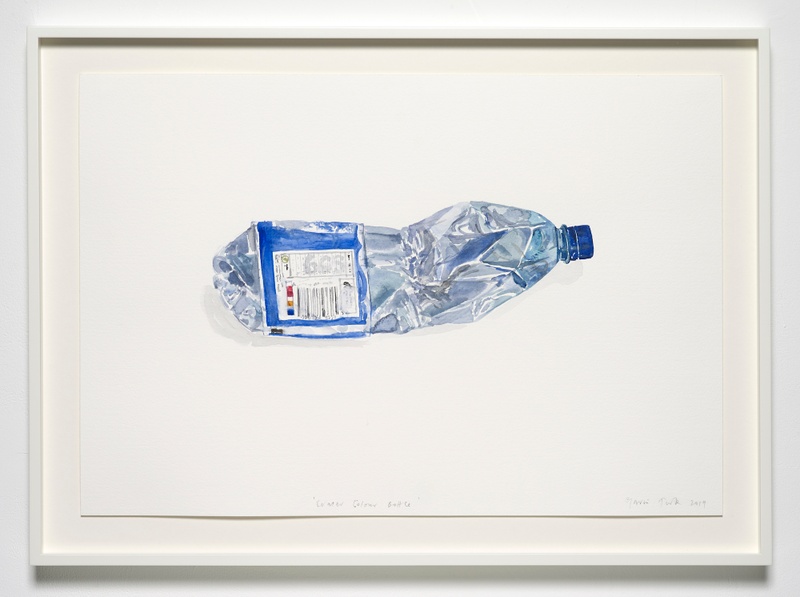

Gavin Turk is a British born, international artist. He has pioneered many forms of contemporary British sculpture now taken for granted, including the painted bronze, the waxwork, the recycled art-historical icon and the use of rubbish in art. Turk’s installations and sculptures deal with issues of authorship, authenticity and identity. Concerned with the ‘myth’ of the artist and the ‘authorship’ of a work, Turk’s engagement with this modernist, avant-garde debate stretches back to the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp. He recently launched a Kickstarter campaign for his project, Piscio d’Artista.

Conversation

On recycling ideas in your work

Visual artist Gavin Turk discusses recycling history and stories as well as physical things.

Why are artists so interested in trash?

I was picking up crumpled cans of pop soda cans off the street one day, and I thought, “Oh, these are cool.” You’ve got this 3D object that’s been flattened into a 2D piece. A bit of the back comes to the front, and a bit from the side goes around to the back. They almost feel Cubist. And they still have this advert on them. But is that can still advertising Coca Cola? It’s just been thrown on the street, and someone has come along and ran it over with their car, and now it’s dirty and filthy and almost rusted. Is it anti-promotion? Or is someone going to see it and still want a Coca Cola?

It’s almost like the yang to the yin of desire. On one side, we’ve got things people desire, and then on the other, we’ve got things people get rid of. I love the idea that we don’t just “place” stuff in the trash heap, we “throw” it. We have to somehow eject it in a forceful way so that we can see ourselves in some distance from that thing. But quite obviously, the thing really doesn’t go away. It’s still there, it’s just gone away from you and possibly got closer to other people or to other situations.

That’s why for me the fascination with waste seems to be about fascination itself. And it’s also so available. Everyone knows what trash is, but we don’t all know quite why we have to deal with it.

The thing is, the sweet liquid inside is kind of worth very little. Most of the cost is in the packaging. So really what you’ve brought is this aluminum can with all this special printed graphics and stuff like that, and the engineering that went in to make it and ship it. But everyone still thinks, “No. I don’t want that,” or, “I want this, the brown, sugary liquid inside, and the can I’ll just throw away.”

I got really excited about the idea of how to remind people of this system of desire and waste we sit in. That system, for me, can be told just by picking up a can on the street.

What about boxed water? It’s a huge thing in New York City right now. It’s become this, “Oh, we’re going to do something that’s elevated,” but it’s still just bottled water.

We don’t have boxed water. I don’t even know what that is. That’s a sort of tetra pack or something, is it?

Yeah, almost.

Gavin Turk’s studio assistant, chiming in: I actually had a box water last week at a hotel. They gave boxed water as a gift. It’s really bad.

Anastasia had boxed water for the first time last week.

There you go!

It’s a new thing, then. Boxed water. I’ve actually got a massive collection of bottles that I find on the street. There’s something about the romance of bottled water packaging. Some water is sporty, others are striped, some have waves to suggest some kind of freshness and natural movement.

Another thing I think about is consciousness. When someone is conscious of something, it’s quite difficult to put that consciousness away, to lose that awareness. Like, if someone gives you a $50 bill and later on you find out that it’s not a real bill, from that point on, you can’t use it because you know it’s a forgery. If you did use it, you would be cheating someone. Consciousness has changed the value of the money you have in your hand. You can’t unlearn that consciousness.

It’s similar to how ads reinforce a cultural system of, “Oh, we’re out of stuff to drink? That’s okay. We’ll just open up a new bottle,” because that’s been part of our cultural lexicon for decades, especially over in the States. But there’s a massive irony in the idea of bottling anything because we’re filling our oceans with micro plastics. A lot of those micro plastics are actually coming from the bottles that we put the water in to carry the water around.

Do you earnestly think recycling will save us?

I’ve got no idea whether we’re going to get saved at all. We just need to do everything. Product design, for one, should incorporate the full life, use, and value of the thing that’s being made so that the problems of disposals are already designed into the product. Recycling is a creative process. It’s taking things that exist in a form, and then looking at a way that you can change that form or keep them going or use them more. It’s like a reevaluation of something.

My childhood was very much taken up with recycling. My dad was a massive recycler. He was a war baby, and grew up rationing everything and hated throwing things away. He wasn’t quite a hoarder, but he was definitely on the edge. Even if electronics would break, he’d save all the circuit boards and save everything in there. And then if something wasn’t working, he would recycle the circuit boards from the toaster and use it in the washing machine or whatever it was.

I grew up on that kind of diet of recycling stuff. It seems sort of normal to me. But for me, I recycle cultural ideas. It’s about recycling history, recycling stories, recycling intelligence—not just physical things.

I like how you’re approaching recycling as a mentality: a relatively simple way to keep things going. It’s very positive, and pushes back against a lot of environmental pessimism I’m hearing these days. How do you feel about nihilism, or people who just put their hands up and just say, “It’s all burning. Nothing I do will help.”

I would say that’s quite normal. I think people generally don’t want to get too bogged down by things. They want an easy life, they want to just move towards pleasure and self-satisfaction. And I think there’s a human part of the human condition that is pleasure seeking. People can even pride themselves on not being bothered. “I’m not bothered. I don’t care.” I understand that. I don’t necessarily think that they’re wrong for thinking like that. That’s just not how I choose to think.

Yeah, I think it’s really important to have a positive dynamic. We should have a sort of positive spin on our lives. If you get more of us positive role models, who enjoy thinking, enjoy cultural engagement, and enjoy recycling things, then you could really inspire others. We just need to find these role models and point people in their direction, and say, “Look, here’s some ideas. Here’s some ways of operating.”

Do you find yourself recycling ideas in your work?

Yes. I’m always recycling. Building a body of work is all about juggling ideas. Often I have partially resolved thoughts that can just float around in my head for ages, then all of a sudden another thought arrives and, hey, presto! But sometimes I enjoy a collage of ideas that I may have acquired from a multiplicity of seemingly random sources that all come together to make perfect sense like a kind of cookery or alchemy.

Can you describe, in your own words, what Piss For Shit is?

The project actually began when I asked myself the question: if I wanted to open an art museum, what artworks would I have in it? How would I fill the rooms?

And the first piece I went to was Manzoni’s tin of shit. This work from 1961 is so ancient now but it still feels so unpassive. I can’t really get past it. It occupies what conceptual art is so solidly. It’s saying, “Everything I produce is art, as an artist.” So if I acknowledge the fact that I’m an artist, everything I produce is art. And the moment it becomes the shit, suddenly you realize it’s everything. It’s everything you’re doing. I’m sure that Piero Manzoni did non-art shits. It just so happened that he took some, and then canned them, and then turned them into art, and then they became art shits.

So I came back to this idea of waste, and came back to the idea of alchemy: he tinned something, and then sold them for their weight in gold. I found myself thinking, “Oh, well maybe what I can do is I could sell my piss and sell it for silver.” But what I could do is sell enough of these cans to buy an actual tin of Manzoni’s shit, which at this point could cost two hundred thousand pounds.

The whole project in itself is a big fundraiser, and then we thought about doing a fundraiser to do a fundraiser, which led to running a Kickstarter.

If someone buys a can, should they keep it forever? Should they recycle it?

Well, yes, I think people would just keep them. But when someone is about to throw that away and someone else has to go, “Oh no, don’t throw that away. That’s valuable artwork by this artist, Gavin Turk. It’s his own piss.” “What? His piss in here?” “Yeah, yeah, yeah.” “Well, I don’t want that. Let’s get rid of it.” “Oh, well let’s try and sell it. Let’s try and sell it and move onto someone else.” It could be that it gets recycled. I haven’t really thought about that yet. You’ve taken me a step further than I’m prepared.

I went to see the body of Lenin at the Red Square in Moscow. You go down these stairs and there’s these gruff guards in this low lighting, and Lenin’s body is there. It looked very much like a sculpture now. It’s 85 years old. There’s a whole university that’s dedicated to the preservation of Lenin’s body. And so, they take bits away and then they work on them, and they research and study them, and it’s all to do with cell breakdown, and why cells break down, and then how to stop cells from breaking down, and how to basically keep Lenin’s body in this place.

It’s fascinating. Lenin’s body has got to be kept because it keeps an idea alive somehow, because it keeps this cultural high point. It keeps him on a mythic level as well as teaching us about biology. It also teaches us about the fact that we have to hang onto a glorious past.

As a 26 year old, how worried should I be about the world ending?

Well, as a 53 year old, basically I go in and out of worrying. I go in and out of worrying, and I think you probably go in and out of worrying as well. It’s not always useful to worry about stuff. I wouldn’t advise it, and I don’t think it’s necessary. But having said that—I hate that word, “but.” In fact, we’re going to get rid of the word “but.” When you have to use but, it creates a problem between one thing and another thing. So let’s not use the word “but.”

I think the human race is moving into a more and more problematic environmental situation, and personally I would advise wising up to it and trying to do as much as you can to maybe affect change. Affect change with what you see as being the right direction and the right way, the future. Go for it.

Gavin Turk Recommends:

5 Books to Read (or Re-Read)

Ken Robinson’s Creative Education

Andreas Mann’s How To Blow Up A Pipeline

- Name

- Gavin Turk

- Vocation

- Artist

Some Things

Pagination