On balancing creative freedom with what people want

Prelude

Matt McCormick is a multimedia artist, who lives and works in Los Angeles and New York. In his paintings and drawings, nostalgia for a fabled past abuts the realities of the “American dream” that confront him daily. His works ruminate on the striking contrast between the physical inheritance of the Wild West, populated with dejected and disposable objects, and the vibrant cultural legacy that remains as alive today as ever before. McCormick’s art embodies the true spirit of America, but also the human condition, replete with renegades, risk takers and outlaws. His work has been exhibited in solo and group shows across the globe.

Conversation

On balancing creative freedom with what people want

Visual artist Matt McCormick discusses capturing the spirt of place in his work, using repeated motifs, and being realistic about needing to make a living.

Every artist has a distinctive style but it’s interesting that you go back to a lot of the same motifs. How did you collect those and define the set? And how do you keep that fresh for yourself?

That’s the battle as an artist because I don’t want to get trapped. But at a certain point, if you’re trying to make a living off of your art, it’s impossible to not be swayed by that. A little context: my parents were both artists and I have a pivotal memory of when my Dad would talk about this in front of me. He had made a whole new body of work, was really excited about it. He showed it to the gallerist that he was working with, and they essentially were like, “We want that other stuff you make.” That really stuck with me because I was just like, “I never want to be told what to do as a creative.”

The symbols, images, and subjects that I work with are very much these classic American tropes that, at least for me, have a lot of meaning behind them. When I use a cowboy, which is the most continuous subject that I work with, it’s not about glorifying cowboys necessarily. Sometimes, sure. But for me, it’s much more of what does that represent? And what does that represent now? Because I’m not approaching it in a cowboy porn kind of way.

For me, it’s more of a visual representation of Americans, and how our ideology has affected the course and discourse of society post-World War II, essentially. When we came out of World War II as these worldwide heroes who saved the day and it led to this time of the white picket fence, and this pull yourself up by your bootstraps—I like playing with that image to express desire, frustration, longing for this promised dream that isn’t really the reality that our generation faces. On a surface level, it can look like a pretty image of a cowboy cresting across a beautiful mountain range. But those initially stemmed from growing up in more suburban areas where you would see that image on a Marlboro advertisement. Or, you’d see it in a movie as this kind of beautified representation of what it means to be an American. Because I’m not trying to pretend to be a cowboy. But for me, a cowboy, a Coke bottle, a pack of Marlboro Reds, a Ford truck, these things are exactly the same. They mean the same thing to me, which is why I bring those images in as well.

But to what I was saying, the cowboy works, so it’s hard to not keep trudging away on that because I want to keep being able to do it, and I got to make money as an artist. The cowboy, on a commerce level, sells a lot better than other images. So, it becomes this push and pull where internally, I’m constantly like, “I just want to do a painting of this thing because I think it might work better in this situation.” But then, it doesn’t garner the same reaction. It’s just the battle of being an artist, and how do I balance creative freedom, but also keep the machine going?

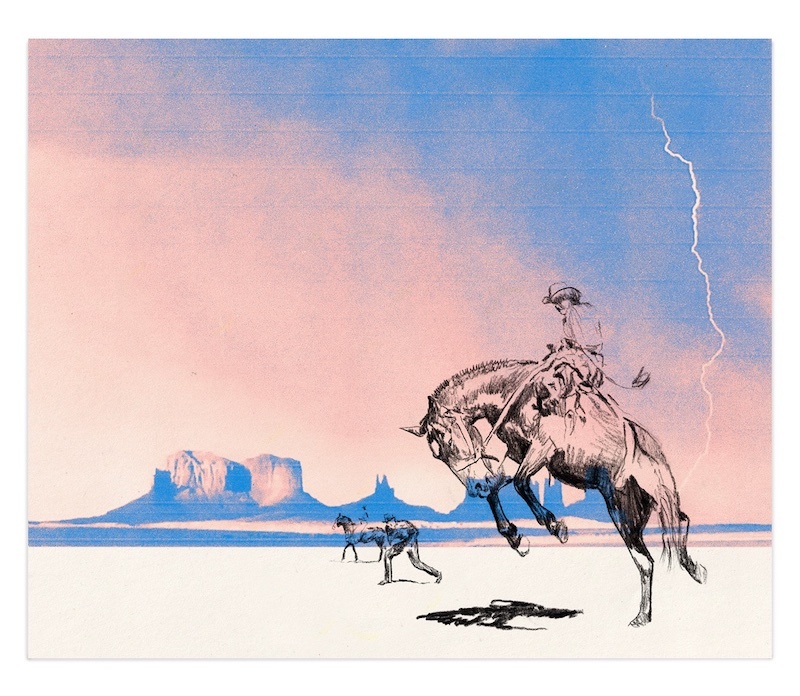

Matt McCormick, Unstable Escalation

As a British person—and probably for people around the world—when you think of America you almost immediately think of a cowboy. Particularly, because in fashion, art, and other spheres, it seems to be everywhere right now. I don’t know if you’ve also noticed that.

Oh, I’ve noticed [laughs].

So these slogans, and cowboys, and landscapes capture this American spirit. How do you pair these things together and decide what works on the page?

For me, a lot of times, it’s dealing with feeling states, and the trials and tribulations of just being a person. When I include lyrics or quotes and then re-contextualize them to create new phrases, it’s to reference what I’m experiencing as a person. It’s why I think certain people can connect to it. Because it’s not just about like, oh, I love cowboys, and they’re pretty, and cool, or they’re badass. I’m trying to talk about the human experience. I’m constantly going back to this imagery, but it is really a starting point to just create a work. And the work isn’t necessarily about this cowboy. It’s been a way for me to open the door to then start. Because a lot of times you’re not going into work being “I have to make this beautiful thing that talks about this, this, this. And I need to project these ideas.” It’s trying to create an image that works together, and hopefully can cause the viewer, or me honestly, just to have a reaction of some kind.

Maybe this is basic but I love the use of color in the landscape. I know those colors are real in America because I’ve seen them. I was wondering whether you go on research trips, road trips, or you take your own photography of places for inspiration?

Short answer, yes. But it started from just looking at pictures, and movies, and having this idea, or a dream about what this landscape and America looked like. I go to Europe a lot. And as an American who looks at lots of different parts of the world, and places other parts of the world on a pedestal, it’s good to be reminded that America’s massive. And you forget that being here.

So, cutting back where this all comes from, before my art was an art career, and I was still figuring it out, I toured with bands. And I toured around America. Well, all over. That was how I finally left America, and got to go to Europe for the first time. But I did a lot of driving around the country, and I had grown up watching and looking at these photos of the New Topographics, Stephen Shore, and all these people having this image of what America looked like. Which is much more like what my paintings and drawings and the rest of it are. Or even my photos, because I tend to focus on the pieces that fit into the narrative that I idolize. But the reality is when you actually drive around the country, it’s a lot of Subways, and gas stations, and TGI Fridays, and whatever. These things that aren’t the beautiful Highway 66 movie version that we have been raised to look at. And it’s interesting.

When I started making this work, I was obsessing over this dream of what America looked like. And the reality is, there are parts of it, and you can still get that, but you have to search it out because what you actually get is much different. It’s Walmarts, and the rest of it. I find a lot of beauty in those things too in a weird way.

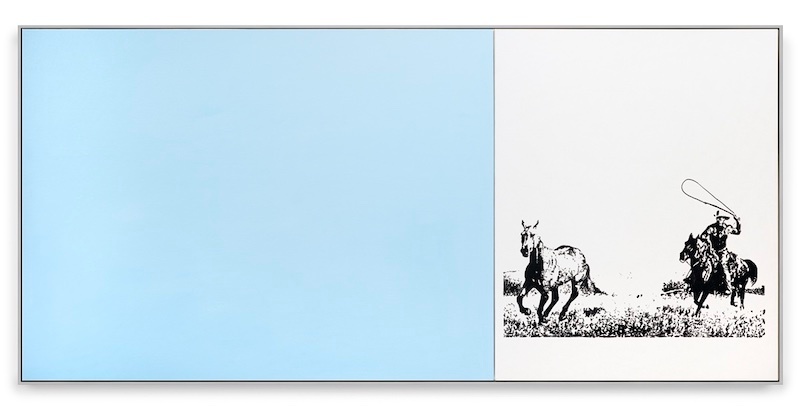

Matt McCormick, Goin Back (Just For A Moment)

I guess looking at those references sustains that dream-like, fantasy quality, which is so nice in your work. Once you do a piece, what is your process after that? Do you go away, and come back to it, and be like, “Have I captured the spirit of this place in this?”

I think that is much more of a subconscious thing. I’m really in my own bubble, which is another reason why working in New York sometimes has been refreshing because in LA, which is where I’ll be for the next few weeks, I have my house, I drive like 13 minutes to my studio in the morning. My routine is very set. I wake up, exercise, go to the studio. I’m there with my team in my studio from 10:00 AM, 11:00 AM, to like 8:00 PM. And it’s very easy to get in just this routine of hammering away at the task at hand, which in LA is much more factory-style commissions or long-term projects and books. Things that are less of the “artist in the studio battling on a canvas.” A lot of my creative process occurs on the computer, which I don’t think many people would assume because my work is done in a much more traditional manner most of the time. Like, oil painting. But essentially, everything I make, I build on a computer in Photoshop before I make it, which might make people think one thing or the other. But I guess it’s the easiest place for me to work through ideas. The hardest part is coming up with the idea. By the time I’m actually touching the canvas, or whatever, it’s already done. At that point I’m just executing. That happens for sometimes weeks, months, digitally, before I even touch what ends up being the work itself.

Your work is deeply emotive for me and accessible, which I like as someone who doesn’t know a huge amount about visual art. When I went to your show in London last year, I went at a really weird hour, and no one was there. And after just going around, seeing it all together with that movie of cowboys you had playing too, it felt like I’d been away on some fantasy trip somewhere.

That is one thing that I want to do more of: do shows like that because it’s the best way to fully get the ideas together. Because if you just see one image on the internet, it’s like, “Okay, cool, this is a pretty Western thing.” And maybe if you follow the work. But going into a space and seeing the different rooms, and the different objects, and all that kind of stuff, it very much helps get the other side that I’m trying to do.

Matt McCormick, Lord Can You Hear Me (How Does It Feel)

Do you have any kind of advice, or tips, or approaches for any kind of artist who wants to capture a place in their work?

I’ve always been really interested in physical spaces themselves. A few years ago I designed a bar in New York, and they brought me in because they wanted to make what felt like a Western dive bar, or whatever. And when I was explaining how you do that to these guys that are New York Club guys, used to making these ritzy, high-end-looking things, but they wanted to make this thing that had the spirit of a roadside shit hole, I was like, “To do that…” I didn’t say it in this pompous way, but you can really study what makes that space. What makes a roadside shit hole so great? For me, why am I attracted to those spaces? It’s because of the life that has lived in them.

It’s not just like, “Oh, let me throw up a neon sign here, and some wood paneling, and we’ll call it a day.” It’s all these small, tiny objects that essentially are the life of a place. And for me, when I’m trying to talk about America, and all that is good and bad in this place, you can build that image, and you can build that world by looking at all these pieces, whether it’s a used tire with grass growing in it on the side of a road, or a piece of trash, or a beautiful horse off in the distance, or all these kind of things. You have to really analyze every detail of a place. And you have to really dig into it deeply, and then, even go below the surface of the visual. Which is like, okay, there’s the people. What are the people going through in this place? What are these hardships?

For America, we deal with these crazy drug epidemics as most of the world does, but ours are always America, bigger, better, I guess. They lead to mental health crises. We have all these gun problems, all these kinds of things. And so, you can touch on all of this. And due to my audience being both sides of the fence…probably far different political leanings than I am, I tend to try to walk that line in a very cautious way. Because I think that one of the most major problems we deal with is an inability to talk to each other anymore. And so, I’m trying to study these pieces that we’re all going through. Because at the end of the day, we’re all humans, and we’re all experiencing life on life’s terms.

Not to go so deep into the minutiae of America and its problems, but you have to study all that to truly get a picture in place. I think that’s the only way to get a full grasp of a place, and a spirit of a place: it is to not ignore anything, whether it’s good, bad, terrible.

Matt McCormick Recommends:

Dreamweapon: An Evening Of Contemporary Sitar Music (Live) - Spaceman 3

Trees Lounge - Written and Directed by Steve Buscemi

If I Could Only Remember My Name - David Crosby

The Lost Coast, California

Ascenseur pour l’échafaud - Miles Davis

Matt McCormick, Angel Of The Field

- Name

- Matt McCormick

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination