On defining your own work

Prelude

Nicola Tyson (b. 1960 London, UK; lives and works in New York, NY, US) attended the Chelsea School of Art, St. Martins School of Art, and Central/St. Martins School of Art in London, UK. Primarily known as a painter, she has also worked with photography, film, performance, and the written word. She has had numerous solo shows and has participated in many group exhibitions. Her work is represented in institutional collections worldwide. In 2024, Nicola Tyson: Selected Paintings 1993-2022 was published. The exhibition, Nicole Tyson: 90s Paintings, featured a selection of her work from the 1990s.

Conversation

On defining your own work

Visual artist Nicola Tyson discusses living with your art, the value of humor, and painting outside of human consciousness.

What is your relationship to material and medium right now? Do you find yourself shifting between different kinds of practices based on how you’re feeling?

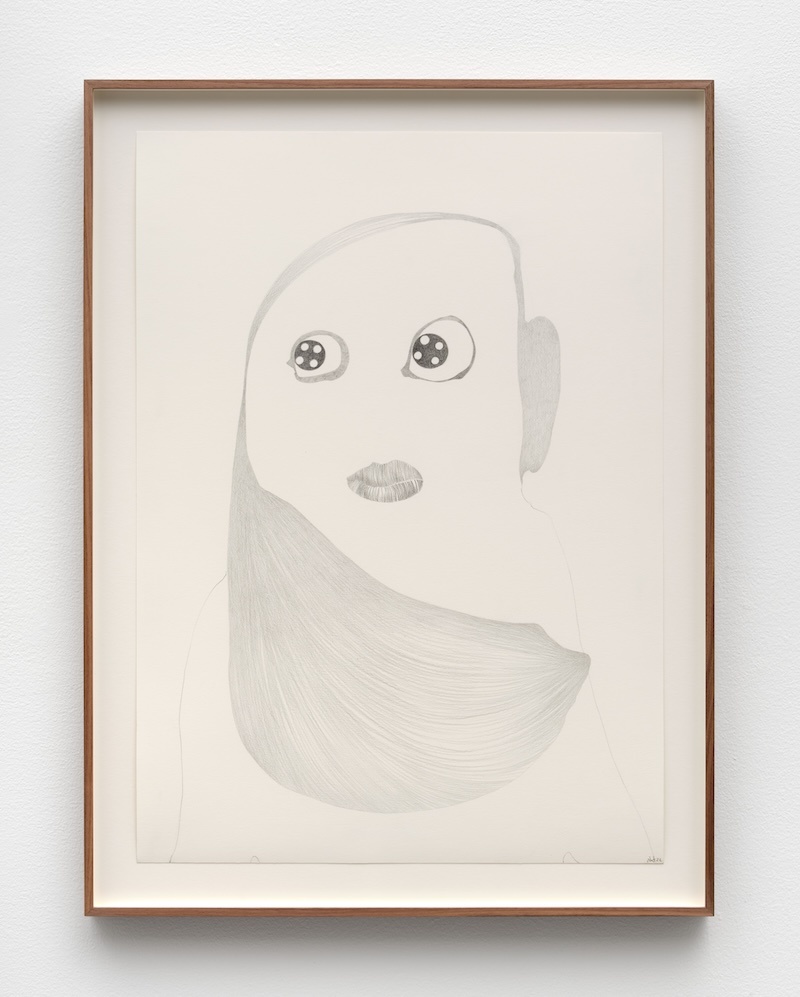

Drawing is a pretty constant thing. I used to use it as a starting point for the paintings, and now lately I’m just working straight onto the canvases and not doing any kind of preparatory drawing. I let the colors work themselves out, which has been really good. It’s something I’ve worked towards, because drawing for me is so important that I have to get away from the line sometimes. I can actually say a lot with a line, and then it becomes like, “Well, what are you going to do in the painting?” So I’m always trying to escape the line.

I know you were in New York City in the ’90s, and then you moved upstate. Now you’re back in the city. How did your artwork respond to those shifts?

I’ve been here a year and I feel like I’m still in this transitional phase, flipping back and forth between how I painted before and a freer approach. When I originally moved out of New York and went upstate, I didn’t see much of a change because I was working out the coordinates of my practice. Landscape and animals and stuff like that would start to appear in my work later on, but now that I’m back in the city, I feel something is changing, but it’s in process at the moment. I have a big show coming up at Petzel in January next year [2025], so I better have resolved it by then. I’m still experimenting a bit.

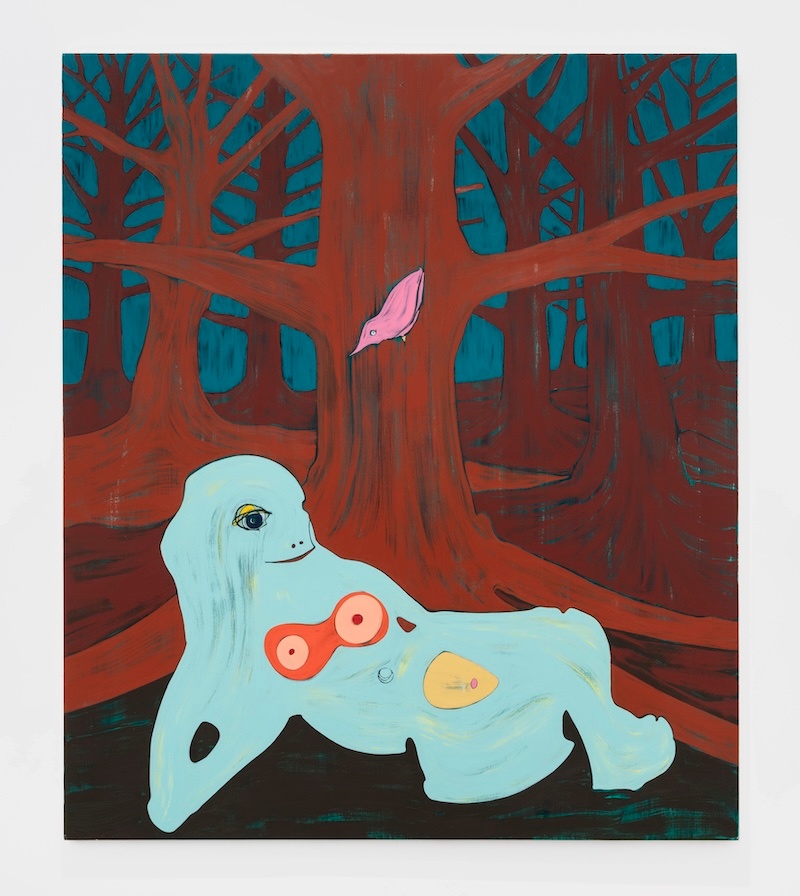

Nicola Tyson, Recliner, 2022, acrylic on linen, 77 1/4 x 66 in, 196.2 x 167.6 cm, Image courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery. Photographer: Cary Whittier.

I love the hybrid forms in your work. How do you approach representing animals or things that are non-human?

Well, I feel most comfortable in that space. When I was a kid, I thought I was going to be more involved in an environmental career, and then in my teens I realized that culture was more compelling to me than working in nature, but it’s always been very important to me. When I lived upstate, I had a lot of animals. I had pet donkeys and all manner of things, so I would merge with their consciousness in a way. I never see anything out there in so-called wildlife and nature as being separate from me.

I want to get away from the human idea of centrality. That became part of my work upstate, because I was surrounded by nature all the time. Even landscapes when I draw them are animate. They have a consciousness. I like to explore that merging or unspoken communication. That’s most easy and immediate with drawing because it has this seismographic quality. You can start registering stuff before you even think about it. I try and keep my rational mind out of things as much as possible and let decisions make themselves organically.

I came up with the term “psycho-figuration” to describe my work flippantly many, many years ago, and it sticks and it does actually describe it, although it was not something I officially would say that I was doing. In the ’90s, hardly anyone was painting, and nobody was doing figurative painting. There were just a few of us, and it was difficult to explain exactly what you were doing.

I’d get labeled surreal a lot, and I’d think well, I’m not a surrealist. So my term, psycho-figuration, was a way of using language to try and explore female subjectivity, to describe something that I felt hadn’t been depicted yet or represented. It was difficult to actually even articulate it, and so that was why I was using that language to just explore and articulate that. Psycho-figuration explains it better than surrealism.

Nicola Tyson, Two Figures Dancing, 2009, oil on linen, 72 x 72 in, 182.9 x 182.9 cm, Image courtesy of the artist.

It sounds like that term, “psycho-figuration,” was your way of negotiating a new space for your work.

Yeah. Calling me a surrealist felt like an attempt to categorize and pigeonhole [my work], and that was completely contrary to what I was trying to do, which was to open up a whole area where new imagery could be found and explored. It wasn’t about going back to surrealism.

Do you think that that still applies to your practice today, that term? Has it expanded or shifted in its relationship to your work?

Yeah. I used to only do figures. Then, gradually, I started to explore consciousness outside of the human. It doesn’t apply in quite the same way, the psycho-figuration label, but it’s still essentially the same thing. I still use unconscious and “unrational” channels of collecting information and responding to it. So it hovers all around there, but I never want to be reduced down to some label. I want to keep it all moving all the time.

There is this biomorphic quality to your environments. I am curious if that’s become more important in your work as environmental concerns have taken more center stage.

I thought that was my vocational future when I was younger. I do very much want to explore the environment. It is pressing.

That’s in addition to my feminist concerns, which I explored earlier on, getting out from under patriarchy. An extension of that is how to get a relationship with the so-called natural world that isn’t completely filtered through all of these male ideas, the naming and labeling and controlling.

I realized that you can have your own relationship with things in nature. When I was growing up you had to know the name of everything, otherwise it didn’t exist. It didn’t come into focus until it was named. You had its name that had been given to it by science. I want to get away from that.

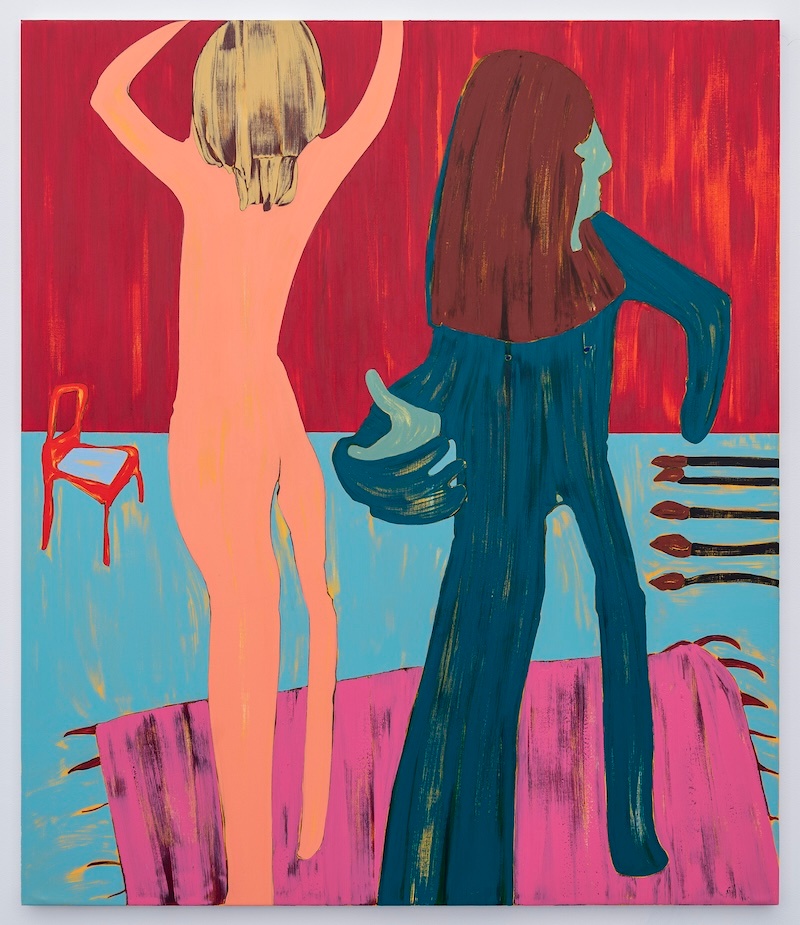

Nicola Tyson, Self-portrait: Artist and model, 2022, acrylic on linen, 77 1/4 x 66 in, 196.2 x 167.6 cm, Image courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery. Photographer: Cary Whittier.

This is helpful for me because I think I’m beginning to understand how you consider your work in relation to feminism now, how those stakes evolved over time.

It has shifted. When I was starting out in the ’90s, women artists were still not really taken seriously. Now, of course, there’s a lot of women operating in the art world.

I mean, we’re not equal yet, especially in terms of money and stuff like that, but I think the visibility and creative authority is acknowledged by everyone, and so there’s no question about that. When I was coming up, it was questioned whether women were capable of having any creative authority, barring one or two exceptions.

Now it’s a very different world. Originally, I was trying to carve out a space where I could talk about what I wanted. Women had always been this passive nude or muse, and I wanted to be a protagonist. I wanted to describe that experience, to say “Here’s how it feels. This is what it’s like to actually live in my female psyche, in that body at that time.”

The other vocational urgency for me was the environment. I’m responding to my own need to understand it differently than the way I was programmed to understand it.

In the end, though, I’m quite strict with myself about how the content has to stay in balance with the internal argument of making a painting. I enjoy the rigor of that. The content has to work within the coordinates of what one would consider to be a successful painting.

Nicola Tyson, Haircare, 2022, graphite on paper, 28 1/2 x 21 1/2 x 1 1/2 in (framed), 72.2 x 54.5 x 3.8 cm (framed), Image courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery. Photographer: Paul Salveson.

Can you talk a bit about your exhibition space in New York in the ’90s, Trial Balloon? I’m curious how that came about and what it was like running that space.

I came over from London in ‘89, and at that point there wasn’t a thriving contemporary scene in London. It was all going on in New York or Germany. When I left, traveling museum shows wouldn’t even stop in London. They’d just go from New York to Paris. It was completely off the map.

So I came to New York. Me and my partner at the time decided to do a women-only art space. It was just our sort of punky attitude, like, “Well, we’re only going to show women. We just want to help women.” I wanted to see what other artists were out there and get a community going around that interest, this urgency of exploring and attempting to represent a particular female voice.

But as an artist running a space, it got really hard. You can’t do your own work half the time. You’re at the mercy of any number of artists who expect you to drop everything because you’ve, basically, set yourself up to promote them, and that was great, but after a while it was very difficult to actually make your own work. But I did find that, during that time, even though I wasn’t working a whole lot, something was percolating. When I went back to making work, I found that something had happened. I had found my own voice.

When you can’t work, it gets dammed up and then it bursts out. It can create a really useful bottleneck. It created a tremendous urgency to speak myself, and that became a useful energetic thing that galvanized me into a different way of working. It was great to have a community of women and a community of artists, too. I’m still friends with a lot of the people I showed there.

Are there times where it’s more difficult to find the time to paint, or do you have a routine that you’re comfortable with?

I’m somebody who finds it quite hard to manage my own time, which, of course, is incredibly important when you’re self-employed, so it’s always a struggle for me. I lived and worked in the same place for 20 years upstate, and even when I was down in SoHo in the loft that was Trial Balloon part of the time, I was living and working there.

I actually prefer that. I don’t like doing 9:00 to 5:00 type thing. At the moment, I have a studio in another part of town, so I’m going in to work.

It’s an interesting experience, but ideally, I’d like to be back living and working in the same place again. It suits my rhythm better, which is much more organic. I like the domestic environment. Going to an industrial space to go and make your artwork is a relatively new thing, and it doesn’t really suit me. I am more of a person who likes to live with my work, to have it as an extension of my life.

Nicola Tyson, Donkey Ride, 2021, acrylic on linen, 77 1/8 x 77 3/8 x 1 1/2 in, 196 x 196.5 x 3.8 cm, Image courtesy of the artist.

I also wanted to mention that I loved the writing in your book, Dead Letter Men.

Oh, that’s great. I get a lot of feedback still about that. It’s amazing how much those letters reach people. They were originally done as a fun thing where I was sending them to friends, and then it was actually Sadie Coles who suggested that we make them into a book, and I’ve had so much amazing feedback. I recorded reading them during the pandemic, and they might be going out on a podcast soon. I wrote them in 2011, and the world has changed so much in the time, but they still really inspire people.

I was weaving in my own biography and all sorts of stuff, so it becomes this soup to describe also where I’m coming from, who I am, without actually describing it directly. Humor’s always the best way to make difficult points.

I had a professor who told me once that tragedy disrupts the status quo and comedy reaffirms it, but I always felt like that was wrong. There are so many examples, your work included, where humor is this transgressive force.

Oh, yeah, that’s interesting. I would’ve flipped those two around. Totally. You can do so much with humor that’s sneaky. You can send in a Trojan Horse with humor.

Nicola Tyson Recommends:

Bespoke tailoring when possible.

The love of a good donkey or two.

Ultramarine.

To hold that bronze age nippled ewer from Akrotiri depicting a swallow in flight .

Talking with trees.

Nicola Tyson, ….and GO!, 2022, graphite on paper, 18 3/4 x 15 3/4 x 1 3/8 in (framed), 47.62 x 40 x 3.3 cm (framed), Image courtesy of the artist and Nino Mier Gallery. Photographer: Jeff McLane.

- Name

- Nicola Tyson

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination