On the unpredictability of the creative process

Prelude

Penny Goring makes paintings, sculptures, drawings, collage, image macros, videos, and poems that are explorations of the contemporary state of emergency. Selected gallery exhibitions include ICA, London, Tate St. Ives, UK, Museum of Modern Art, Warsaw, Campoli Presti, Paris, and Arcadia Missa, London. She has performed her poetry at many venues, including ICA, London, South London Gallery, London, Pogo Bar/KW Institute, Berlin. Goring lives and works in London.

Conversation

On the unpredictability of the creative process

Visual artist and poet Penny Goring discusses putting everything into your work, redefining success, and being surprised by what you make.

As told to Elle Nash, 3279 words.

Tags: Art, Poetry, Money, Process, Focus, Mental health.

Let’s talk about process. How do you know when a piece is done? Do you ever feel satisfied with your work?

A piece is done when there’s nothing I want to add, alter or lose, nothing annoys my eye. I won’t allow a piece of any kind to leave home unless I love it, and nothing is thought of as “done” or finished until I love it. Satisfaction is the pure buzz I get if I finish a piece and it meets my intention, or exceeds it, and emanates its own presence, becomes an entity apart from me that exists on its own terms, and I can walk away, leave it to do my job for me. And that job is communicating with the world, because I don’t want to.

How does a sculpture, or a drawing, or a concept start for you? Can you walk us through your process of an idea to something that is fully realized?

My works start in many different ways, but instinct and emotion always play a big part. If I can feel, visualize, or hear it, or all three, I have to make it. It’s almost as if my work happens to me, like an affliction. Anything can start me off, from a tumble of flowers or abusive government legislation, to an intrusive memory or a few words in a book. The medium I choose will be dictated by the mood I’m in and/or the idea itself. Sometimes I can sense that I need to draw from life or imagination, sometimes to sew for hours, play with MSPaint, or collage with glue, scissors, and magazines, paint intricately or boldly, sometimes only words will do, so I write streams of brain-spew then edit for weeks, months, or years.

Using Pour Doll (2021) as an example of my process for making the doll sculptures—this one sprang from a previous doll, Grief Doll (2019), where I made a Grief Flower that is tied to her torso. It has three long black velvet tendrils, which are exaggerated stamens, pouring grief from its center. I wanted to use this idea again in a different way, so I made drawings in my sketchbook to work out how I could make a doll whose whole “body” poured, what fabrics were suited to her shapes and emotion, and the exact colors she needed to be able to say: “I am so full of torment and sorrow that it is pouring from me; my body can no longer contain it, so I’m gonna be hanging upside-down forever, like a suffering inverted crucifix with midnight blue tendrils of sorrow spilling from my neck.”

Pour Doll, 2021, Penny World installation image from ICA, 2022

She has no head because if the torrent of blue was pouring from her head it could be mistaken for hair, and it needs to be unmistakably not hair and also from her neck because this is an emotion so overwhelming that it is purely physical—there’s no brain involved now, only body. She is violet and dark blues because she is feeling beyond blue and has become what she feels.

That’s the sort of writing that goes on in my sketchbooks when I’m developing an idea. Alongside the drawings, there’ll also be practical and pragmatic diagrams and notes, with decisions to be made about how to construct her.

I’ll draw her template on card and carefully cut it out. Then I place the template onto the fabric, ensuring the warp and weft is in the correct position for my purpose, draw directly onto the fabric all around the template edges with black biro, then hand sew along the lines I’ve drawn with vintage Sylko thread. The color of the thread is always a crucial choice for me—I’ve a vast store of these vintage reels that I have to bid for in online auctions because they stopped making them and nothing you can easily buy is as good. This sewing is pleasurable, it takes hours and can be very soothing, meditative. I turn the shape right-side out, and begin stuffing the shape with hollow-fibre polyester. This is a tremendously tricky, lengthy, and strenuous task, because I’m forcing these fabrics to do things they aren’t meant to do. Sometimes it feels like an act of sheer will. I’ve improvised tools to aid the process, from old teaspoons and paintbrushes. My daughter teases the stuffing before I can use it because it needs to be untangled into soft fluffy clouds that can smoothly fill the shapes I’ve sewn.

Grief Doll, 2019

I designed the template for her three midnight blue velveteen tendrils—there was a lot of trial and error to get them the lengths and thicknesses I wanted. When velveteen is sewn and stuffed in long thin tubes like this it becomes very easy to manipulate the shapes. I coaxed them into my desired wavy positions rather than allowing them to hang rigidly straight. Then I hung her from two nails on my living room wall and lived with her for two or three weeks, because I knew she needed one more element but I had to get visually familiar with her to judge what it could be.

Eventually, I realized all she needed to be complete was a simple flat circle sewn to her stomach area. This circle had to be made from a double layer of her violet lycra and the stitches around its circular edge had to be navy blue thread, quite long, close together, to intensify the colors in that area. There were several gaps in the seams of her torso and legs from where I had stuffed her so hard, and instead of invisibly mending these I chose to sew over them in large navy stitches, to create dark blue notches—as if the blue of her is escaping from her body from all over, not just pouring from her neck.

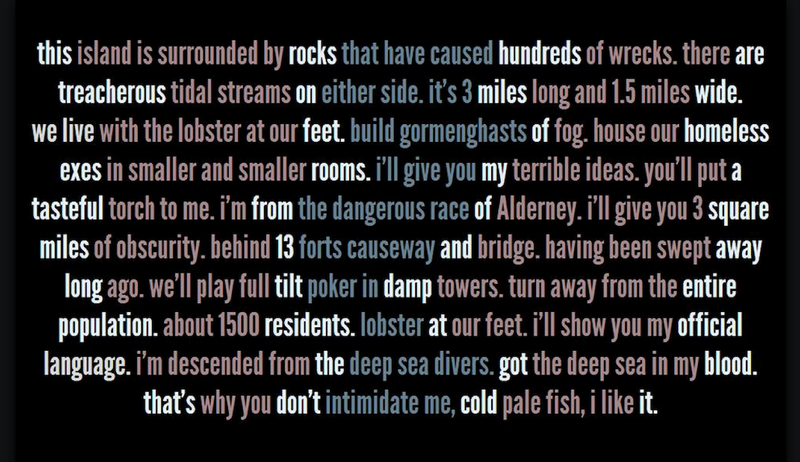

As a contrast to the meticulous doll sculpture process, this is how my poem “Cold Bed Storm Song” happened: I was researching the island of Alderney, where my ancestors came from—the island was once described as “2,000 alcoholics clinging to a rock.” We initially thought our family were deep sea divers but it turns out they were regulars in a pub on Alderney called “The Divers” and when they relocated to London in the 18th Century they opened a pub here. As a recovering alcoholic this struck a deep chord with me. Alderney was occupied by Nazis in World War II as part of Hitler’s Atlantic Wall. They built a concentration camp there. I awoke in bed the next morning with the poem floating just above me, it was a cloud of fog, towers, lobsters, and I was in the crashing sea not my bed, I lived in the fog. I could feel the moods of the sea and the atmosphere of this tiny island, I could hear the words of the poem chanting in my head, so I immediately jumped out of bed and scribbled all the words fast, to try capture this vision, this haunting visitation, then I spent a few weeks on edits, edits, edits.

The experience of making work is endlessly various, surprising, and captivating. I am constantly in thrall.

Cold Bed Storm Song, 2015

How has your process of creation evolved since you began working?

My process hasn’t changed but I am by necessity more organized. I need to keep track of where I’ve stored fabrics, paints, tools etc., in my home, which is a chore because I’m inclined to be chaotically untidy. I keep my documentation and files in order, remember to make note of the dates I finish a piece, what it is made from, dimensions, etc., and I look after the work before it leaves my home whereas before I would bung it in bin-liners, leave it in corners gathering dust, give it away, bin it, or lose it.

I feel like I began working in 1967 at age 5 when I was sent to an Infants School that was conducting an experiment where the pupils were allowed to do whatever they wanted, to see if any of us ever showed an interest in learning to read, write, or do numbers. I never did. I painted, sang, and danced all day every day.

In your Guardian interview in June you mentioned Louise Bourgeois as an influence, citing an affinity with her work. What is it that you identify with in Bourgeois’ life and work?

I first discovered Bourgeois’ work when I was an art student in 1992. She was relatively unknown compared to her status nowadays. I wrote my dissertation on her use of repetition. I got a summer job in the art school library and spent the whole time hiding in the stacks, photocopying from books and old copies of catalogues and art magazines, researching interviews and articles about her, and I found a photo-essay she made about her work and her childhood in a copy of ArtForum from 1982. Her father was having a love affair with the nanny, Sadie. My father had constant affairs. The way Bourgeois spoke openly about her life, and how it directly related to her work was liberating for me because at that time in the early ’90s art was taught to be theoretical, of the intellect, impersonal, ways of making, talking and thinking about art that I was not in tune with. There was no room for vulnerability and emotion, and feminism was an outmoded concept that was sneered at as ’70s retro rubbish. If a student was painting bleeding vaginas or giant dicks they were considered useless twits.

So Bourgeois’ work initially attracted me because it was very obvious that it dealt with personal feelings in a bold and physical way, somewhere between abstraction and figuration, and then this photo-essay sealed the deal, her words were powerful statements I needed to see. “Everyday you have to abandon your past or accept it and then if you cannot accept it you become a sculptor.” “Everything I do was inspired by my early life.” “Concerning Sadie, for too many years I had been frustrated in my terrific desire to twist the neck of this person.” Those wonderful Mapplethorpe portraits of her grinning with a huge dick sculpture, titled Fillette, tucked under her arm, she was messing with gender—those pics are cheeky and magical. I don’t think she’d even made any of her signature spiders at the time.

Then there’s where she lived: a house in New York she lived in for 60 years and it became an extension of her and her work, and she held Sunday salons where younger artists could visit, and when her husband died she immediately got rid of the oven, replaced it with a hot plate. She was living the dream! And with one young assistant. Perfect.

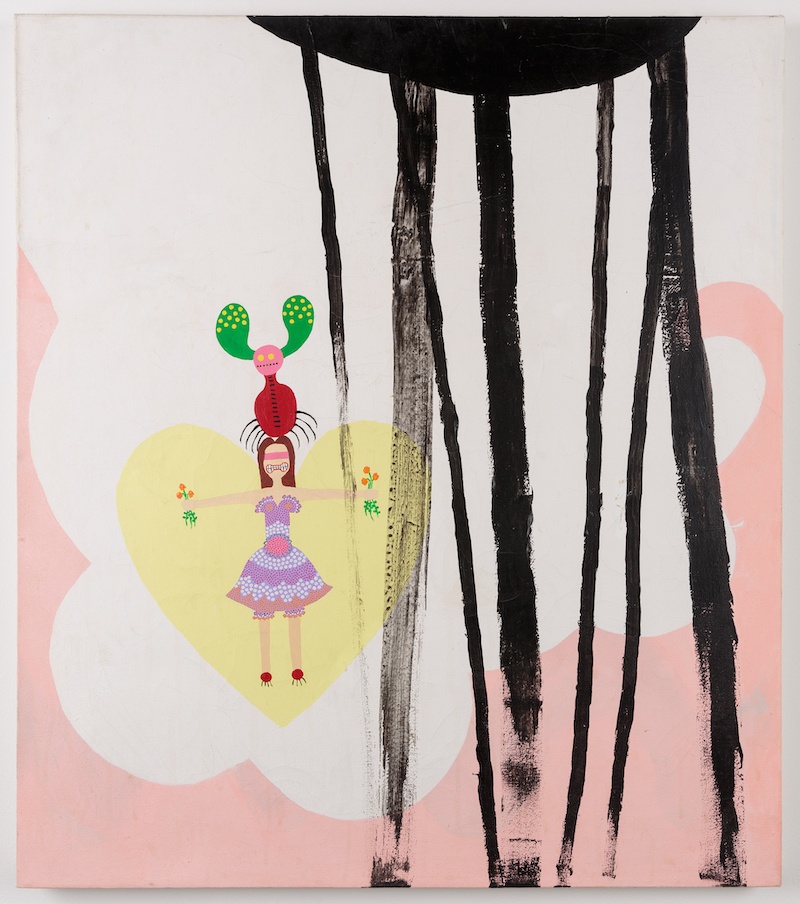

Dim Jaw, 1995

One thing that drew me to you online was that I knew you were a mom and also madly artistic. I have a four year old daughter now, and am often working to balance everything: making money, being present for my daughter, and still trying to carve out space inside of my brain to be alone and to think. I often feel like I’m just surviving day-to-day. How did you balance all of it? Do you have advice for other art mothers?

I wouldn’t ever give advice to anyone, unless accidentally, by example or something. As a recovering alcoholic, I actually do survive “one day at a time.” When my daughter was a child I went to extreme lengths to steal time and headspace to continue making my work—she slept in a double bed with me until she turned 11, we would both go to bed at 7pm and I’d read to her until we fell asleep, then I’d sneak out of bed at 2 or 3am and start my day—writing, painting, etc. until I had to wake her for school. Then after the school run I’d buy food for dinner, dash home, continue making for a few hours. Weekends were tough and the school summer holidays were a barely endurable nightmare. During term time I cut out all my friends, never socializing, and it was only make work, be mum, make work. I keep housework to the bare minimum, we’ve lived here 20 years and it’s a mess but the toilet and kitchen are clean. I deeply resent when I have to wash my hair, shower, or consider my appearance for a meeting, studio visit or opening, and time spent on essential life admin makes me angry and stressed. I must have constant huge chunks of alone time or I feel my brain frying. The way I live is probably too extreme to ever recommend. But stripping it to the essentials is how I manage to function.

What’s the hardest thing about “success” and “making it”? How does an artist live, create, and work?

I don’t think about “success” in that way. All I’ve ever aimed for was to find ways to keep a roof over my head without having to stop making my work—that has always been my focus. I have learned to live frugally. My only luxury is having enough time to do the work. I have abandoned everything and everybody, except my daughter, for the sake of that. I could have chosen to live a safe, comfortable life but “romantic” long-term relationships disrupt my headspace. I never met anyone who didn’t annoy the hell out of me no matter how much I loved them. I became involved with the art world primarily because capitalism demands I sell my work to survive and now I’m 60 and my body is failing me. Poverty is becoming more difficult to shrug off, and the safety nets society used to provide have been torn to shreds.

Plague Doll, 2019

Were there periods of your life where you had great creative blocks, or periods or burnout? If so, how did you overcome it?

I’ve never felt blocked, but when I get burnout it means it’s time to switch to another medium—I jump around, don’t stay still. I do know that when I spend too much time talking about my work, the new ideas recede. What I mean is, I find that the process of making brings more ideas, there’s constant momentum.

Did you ever look long term at your career and think: “This is where I’m going to be in 10, 20 years, and I’m going to aim my arrow here”?

I’ve never thought long term. I take tiny pigeon-steps forward, two steps back, and am content to let things come to me if they will. My anxiety and reclusive nature turn even the best IRL happening into an ordeal that disrupts my headspace regarding my work. I have long term goals for my work, for it to be the best it can be on my terms, for it to continue to challenge and excite me, and there are several projects I’d like to realize before I die.

I think about audience when I’m finishing a piece, or making final edits on a poem. And if I’m there for the install of a show I’m totally focused on the viewer the whole time. If I think of them while I’m inside the process of making or writing I go totally blank, can’t make anything that feels worth making—I become inhibited and self-conscious—it is painful.

I definitely think about what I’m trying to communicate when I’m making, that aspect is integral to the process. I have to ignore some of the totally wrong interpretations people come up with. If someone “gets it” I’m delighted. I’ve been told by ICA staff at Penny World that every day at least one member of the public approaches them in tears over my work, and apparently, the words “WE TRUST IN THE GRIEF OF THE NIGHT,” which is one of the lines from the poem embroidered on Doom Tree, and is also written on one of the Art Hell drawings in the show, is most often the thing that gets them. Also, the image macro we printed billboard size that says: “HOW MANY TIMES CAN I BE RUINED” and lots of people seem to identify with the one that says: “I DON’T HAVE A GOAL—I HAVE AN INEXPLICABLE YEARNING.”

I suffer extremes of emotion every second of my life and I try to communicate these emotions, to get through to people, make them feel something, then feel more. But the bottom line truly is, I do it for myself, it’s how I live. If I were to ignore my urge to make I’d fall apart. And I feel like making is communicating, even if nobody sees it ever. But you don’t need to be polite and you decide the rules of interaction. And when people say my work is ‘brave’ or ‘courageous’ I cringe and feel dismayed, and it brings to mind these words from Jesse Darling’s poem, ‘FOR SARAH, AFTER FIVE YEARS’: ‘…misfits from no-count shit towns forge a lonely bohemia through sheer force of will & the fueling cruelty of others. It isn’t courage, it’s damage’.

Emergency Sticks, Amelia Drawings series, 2017

Penny World at the ICA in London is your first institutional solo show. It highlights themes and parallels amongst a few different series of your work. What was the process of preparing for that like? How did it feel to look at this body of work and think about how you’d started?

To me this show doesn’t look back, because something I made years ago exists in the same timeless place in my mind as the doll I finished yesterday. It’s all happening at once, all the time, an ongoing continuous whole. For example, the Doom Tree I made in 2016 was preceded by a Totem Tree I made in 1992. I still want to make a whole forest of trees.

The process of preparing the show was six months of non-stop hard work, careful thought, tough decisions, and difficult choices by myself and the curator Rosalie Doubal, the ICA team, including all their brilliant technicians, and the Arcadia Missa team.

When I walk into the ICA now, I feel at home. We transformed this huge gallery into my personal space, so when I first saw the show’s content warning it shocked me: “This exhibition includes artistic depictions of nudity, self-harm, and themes of sexual violence, addiction, and death.” Maybe there should be a content warning on my own front door, and my forehead.

Penny Goring Recommends:

The Waterfall by Margaret Drabble. It’s twisted and murky.

“I am for an art,” Claes Oldenburg on his 1961 “Ode To Possibilities”

“Child Abuse: A Project” by Louise Bourgeois for ArtForum, 1982

Michael Clark, “Cosmic Dancer.” One of my living “art crushes.” I’ve been a huge fan of Michael Clark since forever, in 1988 I saw “I Am Curious Orange” at Sadler’s Wells with Michael dancing alongside Leigh Bowery; it was like being at a wild party.

The Andy Warhol Diaries, Edited by Pat Hackett. Addictive.

- Name

- Penny Goring

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination