On coping with pain through your imagination

Prelude

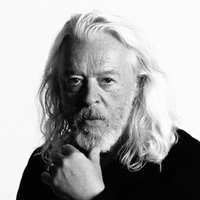

Sara Issakharian (born in Tehran in 1983) completed her MFA in painting at the New York Academy of Art in 2015. She was awarded the 2014 inaugural New York Academy of Art Residency in Moscow, Russia, and in 2015 she was part of the first-round award winners of the Art Olympia prize, Japan. Issakharian’s first exhibition at Tanya Leighton, Los Angeles, “There’s a whole life in that, in knowing that the sun is there,” opened in 2021. Her work will be included in forthcoming group exhibitions at Site131, Dallas, and Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York, in 2022. Her first solo exhibition at Tanya Leighton, Berlin, will open in 2023.

Conversation

On coping with pain through your imagination

Visual artist Sara Issakharian discusses laughing while painting, balancing commercial demands with an artistic practice, and how to not destroy your work.

As told to Claudia Ross, 2810 words.

Tags: Art, Identity, Beginnings, Process, Politics, Inspiration.

How did emigrating to the US affect your creative process or production?

I think most of the paintings are about relocating, if not all of them. The beginning series that I worked on was all about emigration. So I used to paint a lot of animals, always dislocated. It’s interesting because I always say, when you emigrate, you think when you go back home, that’s home, but usually it’s not that anymore.

You go back and you feel like you’ve changed. The place has changed. You don’t belong. But still [Iran] is the first space. I don’t use a lot of Persian images or things that people could recognize and say, “Oh, this is Iran.” But the content of every painting is about the news that I hear or it’s about something that happened to one girl somewhere in Iran.

I think the hardship that comes with emigration gives a bit of taste to the paintings. I don’t like to say artists should suffer. But when you go through ups and downs you will create more complicated compositions, because your mind is not at ease.

You’ve talked previously about your work’s representation of violence against women in Iran. It obviously plays a central role in how you compose your paintings, but does it have a motive? Are you trying to change someone’s mind?

I think if you are born in Iran, you are political. Your life changes so much every day. Sanctions, war, this, that. You are political by nature. So I think I inherited that unconsciously.

Those memories of Iran feel very prominent in your painting.

Absolutely.

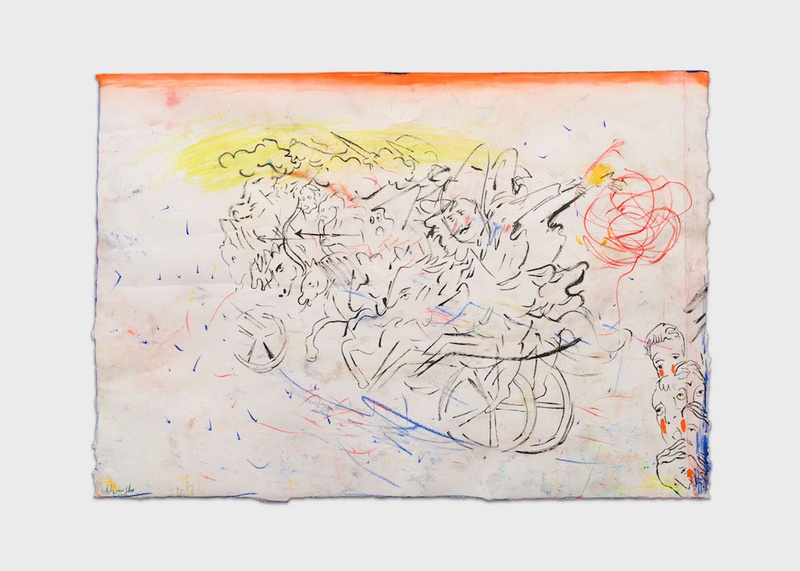

Sara Issakharian, I’m a Hunter, I Hunt for…, 2021; acrylic, ink, color pencil, and pastel on paper; 55.9 x 76.2 cm, 22 x 30 in; Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Dan Finlayson

It’s really visible. I was wondering how you go about painting scenes that are not necessarily pulled from real life. Is it from memory? Is it just from your imagination?

So I think it’s from memory and it’s also from my background. I grew up Persian Jewish, so there were always a lot of stories, mysticism, the way I grew up. So they come back. I always ask myself, “Oh, why did I pick this story?” Then I’m like, “Oh, my grandma used to tell me this story, but in a Persian way.” The same kind of mysticism that I grew up with I’m using [now] in the paintings.

That’s really interesting because it’s not memory of specific events or scenes or places, but memory of central myths or stories that you grew up with.

I remember I used to always draw under the tables when they were bombing Tehran because I was about five or six when they were sending missiles over the capital. The parents used to put the kids under the table. I don’t know how the table could protect you. But I remember that under there, everybody was drawing. I think somehow when you grow up with that kind of event, you don’t want to remember. So if I go back to my childhood, I’ll remember the stories. If you tell me about specific events, I won’t remember the sound of bombs, but I will remember that we were all drawing.

To what extent do you feel that—in your work today—you’re still playing under that table?

A lot. I think even when things go wrong in my normal life, I go to my imagination and I start imagining things. Maybe that’s a way of coping with pain. If something is not perfect in a real world, you just go through your imagination, you make a perfect world, and you just play with that. I think a lot of artists, when they were [children], they did that.

Sara Issakharian, The Crow has Flown Away, 2021; acrylic, oil, and pastel on linen, 184 x 285 cm, 72 1/2 x 112 1/4 in; Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Gunter Lepkowski

The way that you’re talking about your work right now, it sounds like it is really joyful and utopian. And definitely your painting is colorful and vibrant and mythic and poetic, but there also is a real violence and brutality often you paint.

Absolutely.

Do you feel affected by violence while you’re painting it?

That’s a good question because it’s my question, too. There are times that some of my friends from California are like, “Oh, sorry, that’s actually scary.” I’m like, “Oh, really?” For me, it’s not, because I just find it’s cartoonish. I have a hard time to showing [violence] in a straightforward way. That’s why I go to animals. I feel like in a hunting scene, hunting is acceptable, more acceptable if a lion goes after a rabbit or something. Somehow that violence is acceptable. But if I want to paint people and what’s happening to people, that is very difficult for me.

It’s like an allegory or a fable, but you use these images of animals in order to make other people, also yourself, make certain associations that would conjure real world events.

I don’t know if people are much changed by art in terms of making them conscious about things, because people look at art as a beauty, as entertainment. Unfortunately it is. It’s a difficult position for the artists to play that, to see how you want to leave the viewer. Sometimes I like to leave the viewer confused and I like to leave them looking more and more. That’s why I use a lot of smaller drawings.

I keep [the viewer] a little bit busy because that’s not an easy task now—to keep a human being busy with an image because [they] are so busy with other stuff. So I don’t know if I want them to see the violence as much as I want them to spend time. Because once you spend time, the painting itself will give you something. I guess that’s what I’m trying to do in the paintings.

Sara Issakharian, Remembered Landscape, 2021; acrylic, pastel, charcoal, and color pencil on canvas, 193 x 335.2 cm, 76 x 132 in; courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Dan Finlayson

Does the commercial aspect of the art world shape or confuse your practice? Has that been difficult to adjust to?

It absolutely affects you because [the gallery] expects paintings from you in a short amount of time. The expectation is high. For me, really, I just want to paint. As long as I can pay the studio rent and I have my paintings and I’m able to work, it’s great. I know that the art world has ups and downs. The paintings might be in favor now, maybe they’re not tomorrow. Maybe they’re back in favor. So I don’t play those games. I just want to paint.

How do you handle the pressure to produce paintings on a short timeline if it doesn’t align with your creative practice?

If I don’t like a painting or a drawing, even if everybody says it’s great, I tear it down. I throw it away. The gallery knows very well because they sometimes ask about works. I’m like, sorry, I don’t like that painting.

Do you work with anyone else or is it just you in the studio?

No. Just me. I’m so messy that I don’t even know what to tell anyone to do. I know an artist in Germany that when I was in his studio there [was] a team of 25 architects. He would brainstorm with them. He was like, “What is your idea about the sculpture?” Everybody would do something and put it on the table. Then they would decide about one sculpture. That’s a different level of practicing art. I don’t know if I want to be there. Maybe one day I will, but I’m so private and I’m so cuckoo, then I don’t even know what to tell anyone to do. But I would love somebody to stretch my paintings.

Right. I think that makes sense. No one wants to do that. It’s like, you can do that part.

Yeah. That I would love.

Sara Issakharian, The March, 2021; acrylic, ink, pastel on paper, 46.3 x 66cm, 18.25 x 26 in; courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Dan Finlayson

How do you go about composing a painting? When do you decide to stop working?

Oh god, that’s when the gallery wants the paintings mostly. If I don’t have a deadline, I can go on until I exhaust the painting. I create complex compositions in the beginning, and then I keep taking things out. People think that, “Okay, you’re doing this painting and you’re just having fun.” None of that. It’s just like another job. You have to problem solve. Do I put this here? But then there are times in the painting that somehow it’s fun. You don’t have to think about anything. I love using colored pencil because I think it has that naive, childhood aspect to it. When I hold the pencil, then I feel I’m free, but when I hold the brush, I’m like, “Oh, I’ve got a make a mark and does this mark work?”

How does it start? When you said that when you put together a composition, they’re really complicated and then you kind of par down, does it start with just a combination of images or a central idea?

The idea is the story, the story that I hear. I hear about something that happened in Iran, let’s say two days ago, then I’m like, “Okay, I want that figure to be in a center and I want to create a world around it.” But then in the middle of the painting, that story is completely gone and it becomes all about how to solve the painting.

It’s interesting that you pull things from the news or from things that you’re hearing about Iran. What kind of reaction do you have to that story that makes you need to paint about it?

I think any kind of unfairness makes me [paint], especially if it’s about women.

Do you ever find yourself in periods where it’s difficult to paint?

Oh, absolutely. Absolutely. I’ve had three months where I come to the studio and I mean, I do things, but nothing comes. And there are times that you are on a roll and things happen. But when you have a career, you have to make discipline for yourself. You can’t really be taken by your emotions constantly. You’ve got to put them down.

Sara Issakharian, Left Field, 2021; acrylic, ink, colour pencil, soft pastel on paper, 57 x 76 cm, 22 1/2 x 30 in; courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Jens Ziehe

Are there other strategies that you use when you know there are demands on you to produce more work? Are there strategies that you have to get out of that space?

I meditate. That’s a big part of my life. I watch movies. And nature always. Walking, walking a lot and then coming back to the studio. Also, I return to the music and films that I love.

I like that. I think a lot of artists will avoid looking at other media when they’re working to avoid being influenced by it, but I always feel the opposite. So it’s nice to hear that’s something that inspires you.

I always go back to old movies that I will watch maybe a hundred times. And that’s mostly Tarkovsky, Bergman, those kind of movies. For music, it’s Max Richter. I love him. I love, love, love his work. I listen to him night and day. But the latest movie I watched was very funny and was a lot about artists, The French Dispatch.

Oh, I haven’t seen that yet.

You’ve got to watch it. It’s amazing. It’s very artistic. Very funny. Especially the art scene about the painter.

I love that. I’ve noticed a lot of humor in your paintings, too, actually. What role does comedy play in your work?

A lot. I mean, I make a lot of jokes and I have that sense of humor in my life. I don’t know why, but since childhood, I always had it. So I love to bring humor and laugh to the painting. I love it. I mean, I think one day I [will be able to] bring that totally into the painting. Sometimes, when I look at Tala Madani, I think that the sense of humor she has is genius. I think for artists, it’s a sign of genius if you can provide the viewer with humor.

Do you ever make yourself laugh while you’re painting?

I listen to comedy the whole time. It goes between Beethoven, Richter, and comedy.

What kind of comedy do you listen to?

It’s all Persian stand up because I understand the language better. If you put an American stand up, it takes me time to get what is he talking about, or I won’t laugh about it so much because I didn’t grow up with it. But the Persian stand up I’m laughing the whole time… You see, when you pick a story that is about pain, right away I’ll pick something else that makes me laugh. It’s funny, I wasn’t aware of this until you said that.

I know a lot of writers who find it difficult to write about things that are painful to them. They’ll take breaks or something like that. Listening to stand up while you’re painting something that’s obviously moving to you—that sounds like a way of getting through it or finding the humor in it.

You’ve got to convince your mind that it’s all okay.

Sara Issakharian, Pink, Red, Yellow, 2021; acrylic and pastel on paper, 56 x 40 cm, 22 1/4 x 15 3/4 in; courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photography: Gunter Lepkowski

What’s the one creative tic or bad habit you have to fight against? How do you fight against it?

To destroy my paintings all the time. I think my boyfriend calls me a hundred times and he’s like, “Don’t destroy them today.” Yeah. So when the gallery asks, “Where is it?” I’m like, “I destroyed it.” I haven’t been able to deal with it yet.

What is the feeling that comes up? What leads you to destroy the painting?

I feel it’s heavy and I want to get rid of it.

Like it’s a burden?

Yeah. It’s a burden, heavy burden. I’m like, “I don’t want you around anymore.”

Wow.

I don’t know if this would be very delightful for your readers, but that’s what it is. [laughs] In New York, I used to give it to my friends. So they all have my paintings, large, large paintings. But here, because the trash can is very close by and I can walk to it, it’s what happens.

I think most people would say that they get so disgusted or that they don’t like it, but it doesn’t sound like you don’t like it.

No, no. I love them, but they’re just heavy and I feel like I want to be free from them. I never had a feeling of disgust about any painting, to be honest. I just feel that they’re heavy.

Because they are violent or the questions that they’re asking are painful?

It’s technical and it’s also mental. The technical aspect is that I’ve worked so much on it that the canvas doesn’t accept what I want to do on it anymore. I have to get rid of all these animals and everything, creatures, and I don’t want to get rid of them. I don’t want to let them go. Even though I do it a hundred times, but there’s a point where I’m like, I don’t want them to go and I can’t work on it anymore the way it is. So I go put it outside in the garbage.

Sara Issakharian Recommends:

The last scene in Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice.

Sitting in long silence at Vipassana meditation centers

Swimming in lakes

Ice cream in bed

Watching birds fly in groups

- Name

- Sara Issakharian

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination