On accepting that you're good enough

Prelude

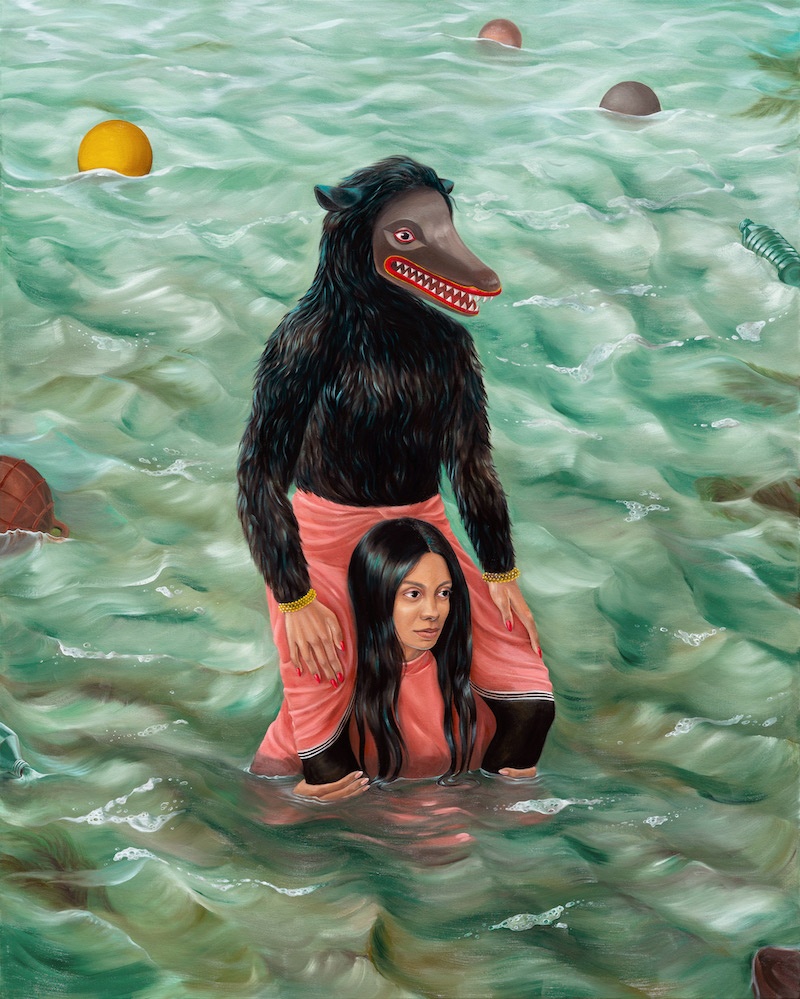

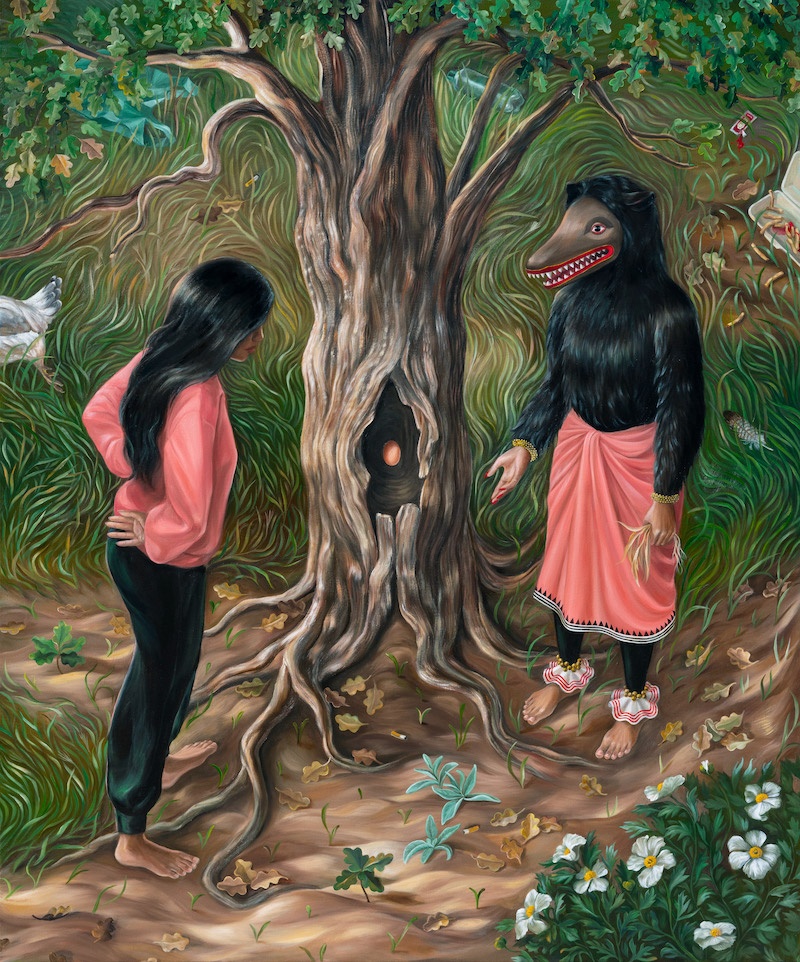

Shyama Golden’s oil and acrylic paintings use figuration to explore the complex and layered ways identity is experienced, performed, and reinforced. Her current series features Sri Lankan masked folk dancers disguised as Yakkas (devil dancers) who traditionally perform in colorful and often comedic exorcism rituals to remove unseen spirits causing physical and mental ailments. The original symbolism of the Yakkas is used in scenes where the artist combines self portraiture with Yakkas who act out the artist’s ongoing inner conflicts. Many of her current paintings also take inspiration from the semi-wild and hilly Mount Washington neighborhood in Los Angeles where she lives. Her work has been featured on covers for The New York Times, LA Times, and Netflix Queue as well as various book covers such as Shruti Swamy’s Archer, Fatimah Asghar’s If They Come for Us, Akweke Emezi’s PET and BITTER and in films such as LITTLE, Fletch, and Boxing Day. She has exhibited at Jeffrey Deitch Gallery NYC and LA, Micki Meng / Friends Indeed Gallery in SF, and Trotter & Sholer in NYC.

Conversation

On accepting that you're good enough

Visual artist Shyama Golden discusses prioritizing your creative work, allowing space for vulnerability, and knowing when to say no.

As told to Eva Recinos, 2490 words.

Tags: Art, Day jobs, Time management, Process, Creative anxiety, Identity.

You worked in graphic design for a decade. During that time, how did you carve out time to work on your paintings?

I found it really difficult to just do a couple hours here and there of painting, or come up with my own ideas for art while working. Even when I was working full-time at a company, I would freelance after work. That would just take up all of my time. And then whatever little bit of free time I had, I’d want to see my friends or something.

What I had to do was have these self-imposed deadlines, and that’s the only way I was able to make work. I would just have to tell everyone, “I’m taking two weeks off.” And that meant two weeks to totally focus and make art. Or a month, or whatever it was. I would have to take blocks of time completely off of work in order to get something done, because otherwise the freelance work would just take all of my time.

Once you decided, “I have two weeks” or “I have a month,” what did it take to get yourself into the mindset of just making art?

It was really difficult, but it helped me to get over all the feelings of self-doubt and “Oh, the idea isn’t good enough.” Having a deadline really just forced me to make things. And then I would surprise myself with what I created afterwards, because I wouldn’t think I’d be able to pull it off. And then looking back, I would always be so glad I did it.

From what you’re saying—you approached it as, “okay, well, I’ve got these two weeks, so there isn’t so much time to doubt.” It’s just about making things.

Yeah. And the time blocks got bigger. As time went by, I would make sure to carve out more time, but it helped in the beginning for them to be short. Because it would just be more pressure on me to get over all of the things that stopped me from making art. Those feelings of self-doubt and everything would get stronger the more I would neglect my artistic side by just doing freelance work or just doing commercial work.

When you did make that shift to painting full time in 2020, what was it like to have more time to make work?

It took a lot more discipline…I’m better at coming up with the ideas that I’m happy with, but the challenges are also bigger because I feel like there’s more pressure to keep up a certain standard based on what I’ve already done. The other challenge is just creating a structure and schedule around what I’m doing and having discipline to get things done over a very long period of time. It’s a marathon and not a race now. So that’s a whole different challenge in and of itself.

Carry On, Oil on Canvas 48x60 inches, 2022

Have you seen what systems work and don’t work for you? Were you surprised by any changes that you had to make?

One thing that’s changed is now, when I’m doing a series, I try to think about it more like I’m storyboarding. I start with all these rough sketches and try to really think about how the ideas go together rather than just coming up with one great idea for a painting and then building off of that. Now I’m thinking a lot more in series. And even when I do think of one painting, I will think about, “Well, how many variations could I do of this? What might happen and what might I discover in the variations?”

That’s always been a challenge for me—to go deep into something. Because I tend to have a lot of breadth and try a wide variety of things. The idea of commitment is something that is much more new for me, [and] that I’ve always admired in other people’s work. But I feel like I lacked commitment in my own work. That’s a big discovery that I’ve made this year.

You describe this cast of characters in your works that are tied to Sri Lankan rituals and spirits—for example, folk dancers and masked yakkas. When did you first begin engaging with these spirits and this storytelling?

I’ve always known about these spirits and these characters because they’re just something that every Sri Lankan person knows. We just have these masks that are part of our culture. People know it on a basic level. They know that these masks represent spirits that scare away other demons or unseen spirits that could cause negative things to happen in your life. So people put them above doorways. That was my first exposure to them, and I was interested in them just aesthetically as art objects.

When it was time for me to create a new series of paintings, I realized that I was dealing with my own personal demons that were stopping me from creating and had been stopping me from creating my whole life. Just believing that I’m not good enough, or that none of my ideas are good enough. And that was actually the strongest, most dominant feeling in my mind at the time. So I thought, “Well, I should just take this feeling and make art about this feeling, because this is clearly what’s dominating my thoughts right now, so I should just see what comes of visualizing this.” And that’s really where I started using the characters in my work.

You also often feature a stand-in character, if you might call it that, for yourself. Often, it’s doubled or standing in with another figure. When did you start thinking about exploring these multiple selves?

The beginning of 2021 was the first time I started to put myself physically in the paintings. I was doing that series—I started it about five years ago—but at first the characters were acting as myself, or they were in place of me. Then I started to think—I don’t have to necessarily fully identify with them at times. They’re a projection of my mind, so I can exist alongside them as well. That’s why I started to show myself alongside them. And sometimes now when I’m drawing them without myself, I feel like it’s more from my perspective where I’m looking out and seeing the projection. Then when it’s showing myself alongside them, then it’s more myself imagining what I look like projecting them.

Incarnation, Oil on Canvas, 60x72 inches, 2022

It’s also about playing with perspective—not only yours, but the audience member who is approaching each piece.

Yeah, exactly. And the ritual is called tovil, which is the exorcism ritual that these characters come from. That ritual has been practiced for thousands of years in Sri Lanka, and it’s very important that there’s an audience for the ritual. So I kind of see myself as creating my own version of this ritual that’s happening to the paintings, and the people looking at the paintings are the audience for my version of the ritual.

There’s this underlying current of how society has confused its priorities in terms of nature and the environment. How do you tie all these themes together?

A visual idea comes to me, and then I’ll kind of sketch it out really roughly, and then I read it back and think about what that image reads to me. Sometimes it’s not the exact thing that I was originally thinking when I drew it, or I don’t even know what I was thinking when I drew it because it’s coming from my subconscious. These images are just coming up and I’m drawing them, and then I’m trying to interpret them myself. And then they start to mean a lot of the things that I’m thinking about. There might be problems with my own way of thinking, but then also problems with the culture that I’m in. And those things are really interconnected. It feels natural that sometimes the symbolism can be personal and it can be about society at large as well.

Definitely. Yeah, I can see a lot of that. One thing that I find really fascinating is how much you share the before and after of painting. You really zoom into specific parts of the composition and show us those tiny, tiny details that you’re working on. Why did you want to share these peeks behind each piece?

Oh yeah, I mean, I love it when artists share a little bit about what they’re thinking. There’s so much pressure for us to be really mysterious and not talk about the work at all, but I just can’t do that. I think it’s almost compulsive for me—to talk about the work and what my thoughts were. That doesn’t mean that’s the only interpretation of the work. I also don’t want to shut down other interpretations.

I love hearing what other people get out of the work, and a lot of times what they get out of the work are things that I’m thinking about, but I didn’t even realize that I was putting [that] into the work. The process of sharing the details—it’s an excavation of me looking at, “Oh, why did I put these specific things where I did?” And a lot of times it does tie back to things that were really on my mind at the time I was making the painting.

There was one piece that I remember seeing you posting the process for, and then you were like, “I had to redo this entire row of teeth. I had to redo this entire mouth.” It’s interesting in terms of showing it’s not always a smooth process.

Oh, it’s definitely not. And there’s a lot of struggling on the way to getting to the end of a painting. I’m very sensitive to the balance of what the painting is giving me. And I do, a lot of times, have to go a little bit too far to realize that I need to undo a few things and bring it to a place that feels like it’s giving the right energy, or telling the right story.

You recently posted that it had been a really busy few years for you, but that you started saying no to more things and yes to the opportunities that had synergy with the themes you explore. What advice do you have for artists who feel like they have to say yes to everything that comes their way?

Yeah, I completely understand that. It was not something that happened overnight. It wasn’t like a binary thing of saying yes to everything and then saying no to everything. There was a lot in between—figuring out, “Okay, now what are the things I say yes to? And now what are the things I say no to?” And I think the biggest thing is that you have to think about it before the opportunities come. Because when the opportunity comes, the person asking you is going to be so nice and you’re going to feel so easily swayed—if you haven’t already thought ahead of time that I’m not doing X, Y, or Z. It becomes very difficult to draw the boundary in the moment.

That was an important thing—to sit down and independently think “What are the criteria for things that I’m going to say yes to and what I’m going to say no to? What are the things I’ve regretted doing? What are the things that I was glad I did?”

If a certain type of project comes along—for example, a book cover—that is something that I feel like really aligns with the kind of work I’m already doing and the themes I’m already thinking about, I would still be open to it. But it would just be very rare.

The Passage, Oil on Canvas, 60x72 inches, 2022

I’d love to also talk a little bit about your series We Are Not Alone, and especially the theme of centering figures from communities of color. Do you feel like this is something that, in terms of the art world, has changed since you have begun? Are you seeing more artists of color being highlighted?

I definitely see more artists of color being highlighted, and I think there’s room for that because we all have different perspectives. There should be more than one story. I see that as a positive thing. In my own work, I’m currently focused on telling my own story. The current paintings are more involving self portraiture—but I really miss drawing other people as well. I mean, honestly, drawing myself is very difficult for me. It feels cringey or something.

But that’s why I’m leaning into it, because it feels very safe for me to draw other people. Drawing myself—it feels vulnerable and I think that’s why I am trying to push through that before I go back to representing people other than myself.

After the Rains, Oil on Canvas, 60x72 inches, 2022

I wonder if you have any advice for other artists who are dealing with that, too—trying to be a little bit more vulnerable in their work. What are some practices or approaches that have been helpful?

Whenever I’m going through something that’s difficult for me, I’m never the only one. And usually if you’re honest about it and you talk about it, you’ll find those things that are the most personal are the ones that resonate with other people. It just seems strange. It’s kind of counterintuitive — because the more specific you are, that makes it feel random, but it actually tends to be the exact kind of work that resonates with people more. Not that that should be the goal of making it, but I’ve found comfort in that. Just knowing that nothing about me is that special. So everything that I’m going through is an experience that’s shared with other people, even if it’s not with every person.

And it ties into that idea of learning what other people take away, or what other people see in each composition that you might not have even anticipated.

Yeah, I love that. That’s very rewarding for me to hear. It’s really nice after creating something to hear the different interpretations and ways that it can resonate with someone else that I wouldn’t have even thought of.

Shyama Golden Recommends:

The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida by Shehan Karunatilaka

Heaven No Hell by Michael DeForge

Spirits Abroad: Stories by Zen Cho

Alejandro González Iñárritu’s Bardo

- Name

- Shyama Golden

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination