On how your work can push you to where you need to be

Prelude

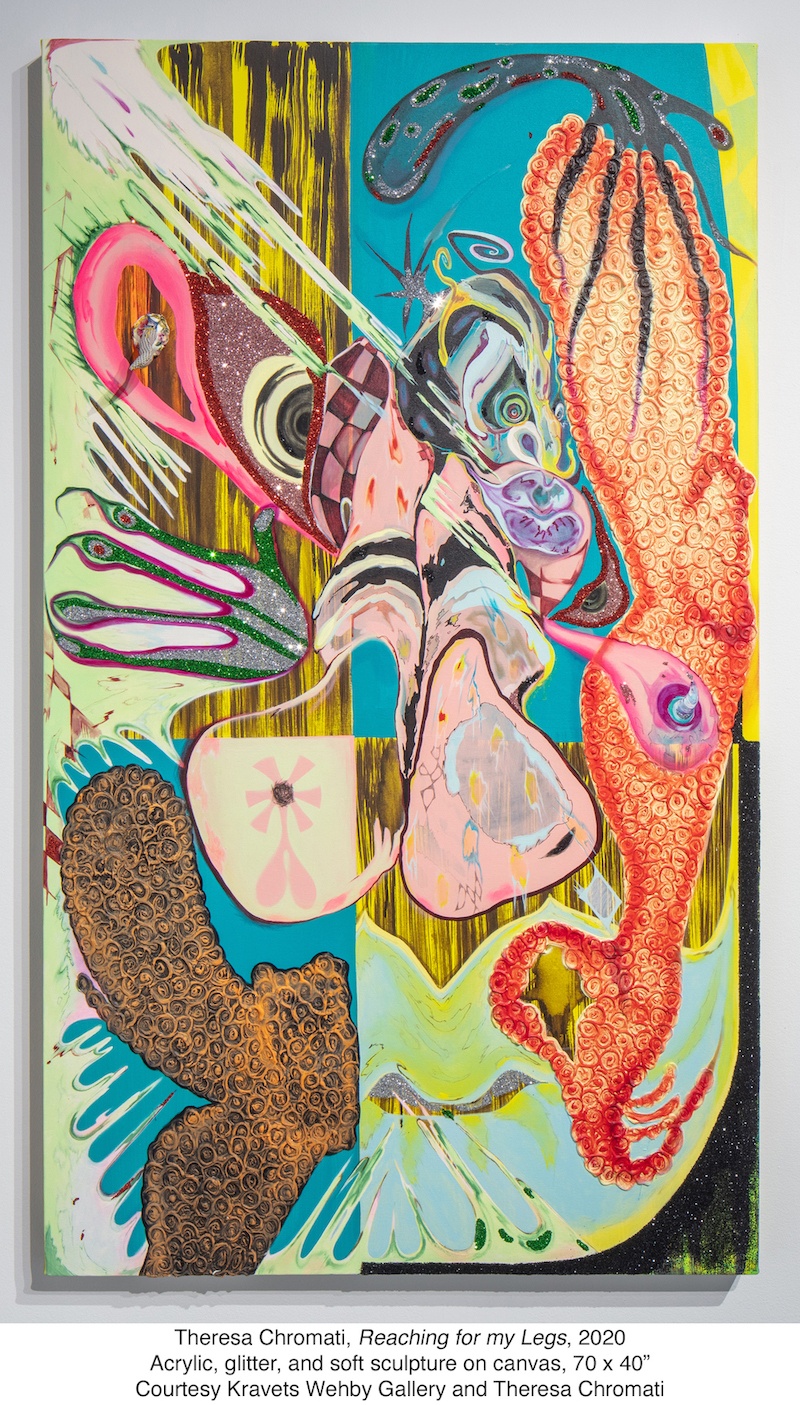

Through fragmented forms of desire and figuration, Theresa Chromati expands the boundaries of painting as well as identity-based art. Her experience as a Baltimore-born, Guyanese-American woman now living in Brooklyn informs her practice, as does her fluid understanding of painting and design, which she began exploring as a student at Pratt Institute. Since then, Chromati’s large-scale works across media have garnered critical and institutional attention for their displays of pulsating color, controlled chaos, sensuous texture, and constant motion.

Conversation

On how your work can push you to where you need to be

Visual artist Theresa Chromati discusses letting the work lead by example, making no mistakes, moving through discomfort, and remaining open to ideas.

As told to Annie Bielski, 2634 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Mental health, Time management, Inspiration, Collaboration.

I want to ask you about the title of one of your paintings from 2020, In-between space… (Note from a scrotum flower: I’ll be with her when she stands again. There to illuminate the way when her darkness wraps tightly. There to offer balance in breath and movement. There until she realizes I am her and she is me. Perhaps she knows, but enjoys the idea of external company).

Wow, that’s beautiful.

It is!

I’m like, “Which one is that?” I haven’t read that in a while, apparently.

I really like that this title is a dialogue with a recurring motif in your work, the scrotum flower. Your titles help expand on the world created in your paintings. This painting in particular is also portrait orientation and four feet tall. Do you ever think about painting as a mirror to you?

I see what’s happening in the painting as a connection to me. The work is centered in figurative abstraction that is also somewhat portraiture that’s autobiographical. But then once everything is on the surface, it feels like it’s taking on another life of its own with the essence of the life that I’m living here. So I feel connected to it, but I feel like what is happening in that realm leads in so many different directions, and it’s a really intimate back and forth between me and the beings there. I do feel that there’s a deep connection.

That particular painting, wow, I didn’t have a chance to sit with it. It left the studio kind of quickly, that’s why I responded in that way. But that actually was the first one where I centered the narrative of the scrotum flower in the title. The work has so many different entry points, but I like to use the title as a way to expand and provide various layers of conversation to lead with. The scrotum flower in general is this motif, this symbol of power, and power in conversation with the balance of feminine and masculine energies. So [the scrotum flower] flows around the central figure, or at times she’s holding on to it or in direct conversation with it. It’s really just an example of her in proximity to her own powers and her own growth. They usually just had a presence within the work, but I felt like by adding a note directly from this symbol in the title, it opens up a different dialogue. It is also a fragment of her and her energy as well.

Is it always the same her?

It’s always the same her. They always look different. The central figure remains the same. The scrotum flower, eyes, and lips that appear in some of the paintings represent internal energy, intuition, something that’s inherited, [and] opens up the conversation of spirituality and this inner voice that women have. So throughout the central figure’s journey, she’s accompanied by these symbols and comforted and propelled by them and caressed by them, but they’re also forms of her. Sometimes we have these energies within ourselves that perhaps we’re not completely aware of at the time, or in some situations we may ignore this inner voice or guidance. So it’s really just shedding light on the back and forth of listening to your own thoughts, leaning into them, or on the flip side then ignoring them.

You’re in your studio now. What is a good day in the studio?

A good day is when I’m not being pulled away. Right now I’m working on a new body of work and I’m getting deeper and deeper into building up layers of the background and making them super intricate, where you can’t decide where the beginning or the ending is, and then committing to where I want to place the central figure. Today I got a chance to start to build the layers of the central figure and add in some really graphic elements. So yeah, a good day is building layers, looking, stepping back, and not being pulled away. It’s really important for my practice to have that space and time. It’s world making, it’s mark making. Doing and then stopping, spinning around, looking out the window and then coming back to it is really important. Right now my dog’s sitting down eating a bone, and there’s some soft sculptures being made in the other room. Just hearing a sewing machine is very therapeutic.

You mentioned not getting pulled away. How do you set boundaries with your time?

I feel like with each year you’re starting to navigate new things, new relationships, new projects, your practice is expanding. As it’s expanding, you’re constantly figuring out new boundaries and new processes of working and seeing and figuring out how much space you need from each one. As far as setting boundaries, I’m still working on that. I’m working on not having to step away as much to do that other work that takes away from the essence of what this is really about. But it all is important.

How do you start a painting?

The starting process has changed over time. I go back and forth from knowing exactly where I want to place the central figure and doing that first and committing to her and then building the world around her. But more recently, between the body of work I did last year and what I’m working on now, I’ve started to commit to building up the background layers slowly. Putting a wash down and building up a lot of different transparent layers that have their own energies, and then starting to rip that energy apart to then create a new form or a new structure. That language, in general, is also what this is about. Ripping and expanding, shedding and rebuilding, that push and pull of building the surface so that she has this foundation and that it feels like a more consonant structure. I’m liking that relationship to the work.

What’s your relationship to play and experimentation?

There’s definitely a lot of play and I feel more balanced when that is happening. If I’m not laughing or if I don’t smile at least once when making the work towards the end, then it’s not finished. Humor is definitely a part of my practice. I feel like, as things get more intricate, as the content and the visual language gets heavier and the density expands, I still want to keep this element of humor and its jovial essence. We’re talking about the layers of women and we have desires, we have rage, we have exhaustion, we’re light, we’re dim.

I like to think that what I’m working on right now is just more is more. How much can you put into a space? There’s no real definition of how much is too much. Once I realized that, I realized that I wanted to add that in a work. How intense can I make something? Even if it feels uncomfortable, there’s so many nuances in discomfort, so play is an important part of that. I feel like there’s discomfort in play and play in discomfort. There’s desire in play. Sexual tension can also be a form of play. I feel like play is in so many different places and life in general is play. That’s been a way for me to heal and to find ways to breathe, through play.

This is a really big experiment phase for me right now. Taking the foundation that I’ve built the past several years and seeing, okay, we have painting, you feel confident within figurative abstraction. You have digital making. I’ve also been working with a producer in Baltimore called Pangelica and we’ve made maybe five soundscapes. Usually they play at every solo show that I have. So at this point I’m taking all these forms of what I’ve built this foundation on and starting to rip it apart and see how deep each one can go. I’m experimenting with how I start and finish a painting. I’m experimenting with texture. I feel like there’s no mistakes. Especially when the practice is centered around this density and personality and bringing all of yourself into a space and just being like, deal with it.

I love “It’s not done unless I’ve smiled or laughed.” There’s knowledge in play and humor. Will you say more about play and discomfort?

I feel like a lot of times, people [say], “Okay, this person is confident. I’m reading them as powerful. They’re showing up in this full way.” Rarely do we think about how they’re getting there or what other feelings they’re feeling in that space. I feel like people often read the exterior and what that looks like, or the things that people say that are confident, but in the moment, everybody has these nuances and layers and moments of discomfort to get themselves there. You can start one way and then present in a different way and get the things done. I feel like in general, that’s what I’m speaking on—all these elements and feelings that aren’t really put to the forefront in order to present and share balance in power in your daily life or in any conversation. And as far as just trying new things, you could have an amazing time exploring, but there could be elements of discomfort getting yourself there or even bringing yourself to even start.

I see pleasure as this cycle of the story of discomfort, desire, and then resolve. Even though there is not a timeline, pleasure could be placed in between discomfort and desire [or] desire and resolve. It’s those three things that are markers to me, [and] at any moment you can move backwards or forwards or just start the whole cycle over again. I did another interview and someone had mentioned pain. I was like, you know, I never say pain. It made me think that when I actually see the word, I don’t resonate with it or want to present pain. I identify with discomfort because discomfort is so open. The source could be so many different things.

Do you ever scrap a painting?

No. I just keep going with it.

I thought you might say that after hearing you talk about moving through discomfort.

It wasn’t always like that. I think certain things, hitting certain roadblocks in life and certain walls at a certain point, you realize, okay this is reoccurring, something that you can’t run from. We could, but it’s not really my thing to run from and close that door, because you will hear it banging for the rest of your life. Instead of just shutting it out, welcome these feelings and these emotions in your everyday life, in you walking down the street, traveling, in your bed, in all of your relationships. One, it’s honest. Spending time with things that might not feel conventionally pretty or beautiful, I actually think it will get you further. You know, who wants to live a lie?

You’ve said that you were nurtured in the arts from a young age growing up in Baltimore. What would you say to your younger self?

I think about that a lot in that I always had it. I think about certain conversations or moments when I was younger and I think about who I am now. I feel like where I am now, I’m starting to want to stay in that purity of where I was then, like, “Okay you’ve always been this way. It’s just you were talking to kids or even when you were talking to adults, you were always firm, knew what you wanted.” I also don’t respond well to “no.” Even when I was a child I was just like, “why you telling me no?” Even with relationships and how I maneuver through space—I don’t keep everyone, it’s okay for you to walk away. I think as I got older, I started to feel bad about that, but then I just started to think about how I was when I was a kid and I would bounce through so many different groups and I hung around so many different adults. I’m starting to realize like, “Oh, this was a friend and this friend, blah, blah, blah, they lived in my neighborhood.” But every time I’m talking about them, I’m just talking about their mothers and what I would do with their moms. I would go over to their house and I wasn’t even playing with their kids.

I had a lot of freedom when I was younger to navigate the city. Once I started catching the bus when I was eight I just had my own life. I feel like [my mom] did her job. I had a good head on my shoulders and my ethics were in line and we had a super open relationship as far as communication. But I was navigating the city and I was reading body language and listening to conversations and being on the bus and seeing how people got into altercations or how certain people resolve things. The city was just so lively and honest and straightforward. You just start to put things together, like if you do this, this could happen. If you don’t do that, that will happen. Being around all these different women who weren’t my mother and lived different lives, I really feel I owe so much to those experiences because I got a chance to see a Black experience within Baltimore through so many different lenses. I got a chance to see so many different cultures from so many different economic backgrounds, so when I was growing up, I never felt blocked in. Everything was super open. I didn’t start thinking about restrictions until I got to college and moved to a different city. I think that is why I navigate through space in the way that I do.

When you’re in spaces where so many things are restrictive and a lot of people just live within them and don’t push back, you start to absorb and it becomes taxing. I’m in a space where I’m just constantly thinking, “Okay, remain open, keep going back to what you had.” I think within the work and in the practice there’s no mistakes, it’s open, it’s motion. I feel like the work leads by example. The vessel that I’m in here desires fully to maneuver as the central figure that’s in the paintings. My experiences here feed into her experiences, yet it’s a constant back and forth. The work pushes me to where I need to be. It’s like creating this tool. It’s kind of like what I’m talking about with creating these various motifs, like with the scrotum flower. The scrotum flower is this idea, symbol of power, and yet is an extension of her. She uses it as a form of support, and yet it’s a connection to her. Me and the actual work and the practice, it’s the same thing.

- Name

- Theresa Chromati

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination