On building tools for better worlds

Prelude

Partner & Partners is Greg Mihalko, Erik Riley, Zach Mihalko, Devika Sen, Lulu Johnson, Logan Heffernan, and Maddy Bruster. Their worker-owned design practice focuses on print, exhibition, interactive, and identity work with clients and collaborators in art, architecture, government, and activism. P&P was founded in 2013 and prioritizes projects and groups that promote social, economic, and environmental justice, with actionable visions for a just future.

Conversation

On building tools for better worlds

The designers and co-owners of Partner & Partners discuss horizontal operating structures, viewing design as a tool, and making ethics a cornerstone of "good" work.

As told to Mikki Janower, 2537 words.

Tags: Design, Business, Collaboration, Process, Politics.

What inspired you to structure yourselves this way?

Erik Riley: I think it just goes back to the original ethos of the studio being non-hierarchical and flat in its structure. We were already operating that way, with limited hierarchy and democratic decision-making, so we were like, why don’t we just formalize it as a legal structure?

Greg Mihalko: I was working at an agency that was very hierarchical. This was at the same time as Occupy Wall Street was happening. The way that those working groups were organizing was a concept that I started to understand.

Devika Sen: We were surrounded by, and looking at, models with the same kind of operating principles. For me, it was artist collectives, similar to Interference Archive and Justseeds.

Greg: There’s a really antagonistic relationship between workers and their bosses. But as a worker-owned studio, there’s no antagonism between who’s doing the work and who’s owning the labor. I think how we orient ourselves as designers and workers is a very clear political decision. We sincerely believe that another world is possible if we organize, and organize ourselves differently. So if we care about self-determination, and care about everyone having a sense of autonomy and dignity—why wouldn’t we, as a studio, organize ourselves on the path to the world that we want to see?

Would you mind sharing the resources that helped you transition to a worker-owned operating model?

Greg: When we made the decision to become a co-op, there were a couple organizations in New York—there’s New York City’s Network of Worker Cooperatives, and there’s Democracy of Work Institute—that acted as a funnel into getting a legal partner to help us formally transition. We went through a 3-6 month period of hashing out an operating agreement and understanding how democratic decision-making would work in this structure. We signed the document at the beginning of the new year, so it was a clean break.

We now work with the city on a project called Owner to Owners. We design the collateral and graphic materials to help build a better referral process for this organization that had funded our own legal fees, so that if other design agencies around the city are interested in this, they can go to Owner to Owners and fill out a form, and someone will be in touch. There are a couple other studios thinking about doing this already, and we think it will snowball from here. We want to work on this stuff with more design studios that want to be champions of this; it’s an important part of why we’re structured this way.

Some of you joined P&P as interns, or straight out of school. How does it feel to know that you’re integral to the studio’s mission, but also that you bear an equal responsibility to the company?

Lulu Johnson: At first I was an intern, and then I was an independent contractor, and then I got hired as a full-time employee-owner. That was an interesting transition. As the year went on, we had to hash out more of the logistics and figure out ownership responsibilities. I wasn’t very good at it at first, because it’s not something I ever expected as a young person, to have that sort of agency and responsibility.

Devika: It’s really exciting, as a young person, to be a co-owner of a business. It’s very common to be taken advantage of as an emerging designer—working long hours, being underpaid, not feeling a sense of worth—and I never felt those things working here, even as an intern. I guess we were in some ways thrown into the deep end, but Greg and Erik and Zach fostered a learning environment where the walls were broken down. All of a sudden we were looking at the books, looking at financials, learning to put together scopes; all of this stuff was getting folded in, but it felt very natural. There’s still learning to do, but we’re getting better as time goes on.

Zach Mihalko: Greg and I didn’t know any of that stuff either. But we’re trying to share as much as we can.

Devika: For lack of a better word, there’s no gatekeeping of information.

Greg: From the perspective of somebody who once ran this entire thing and now doesn’t have to, a co-op is a much less stressful, much more loving environment in which to run a business. There are other people who can pick up where you leave off in any aspect of the work. You have your partners, your co-owners, in it with you.

Logan Heffernan: Part of the benefit of things being so horizontal is that things that are new don’t have to be scary. Prior to working at P&P, I had a more traditional studio experience where there was tension between the people who did the work and the people who made the decisions. There were a lot of days when I would go home uncertain of the path I was on; I felt alienated from my labor and from what we were producing as a studio. But because of the way we work here, I feel a sense of connection to what we’re doing.

Lulu: In equal parts, people put a lot of trust in you to figure things out and do things well. But you also have people to lean on when learning new things.

How do you make decisions in a non-hierarchical way?

Greg: There’s a clause for conflict resolution in our operating agreement that we thankfully have not had to use or discuss. If a conflict happened—let’s say if we wanted to move the studio—we would need a consensus minus one among everyone involved. Big decisions: what kind of work we take on, how we’re going to invest in our business, whether we raise our salaries; are formally and democratically decided.

So with everyone giving and receiving feedback, there’s no singular arbiter of taste.

Devika: There’s not a lot of formal internal feedback. A lot of it relies on the client. We’re not working for each other, we’re working for external clients, so we usually prioritize their feedback. But three of us will all work on a project together and each produce a visual direction, and during that process we can provide feedback for those directions. And as the project goes on, there are more opportunities for internal feedback and improvement.

Greg: A few of us had been working on a pretty big website project, relatively siloed, and before our presentation Devika said, “Hey, I have some thoughts, can we talk about this stuff?” I think at a traditional studio that would be very much out of line, but we’re not afraid to approach each other in that way. It was great to have a pair of fresh eyes, because barreling along heads-down, we hadn’t been able to see what Devika was seeing. Her feedback helped shape the project in a way that was refreshing and necessary.

Logan: Because there aren’t strictly assigned roles and confines around our process, we allow for moments like that. In that instance it was really helpful in moving the project forward.

A quick note about feedback between studio members and how we work on stuff—and this isn’t to be anti-intellectual in relation to design—but I think it is important that we do identify our work as a service. As much as we all care about our practice, we’re careful not to get so involved in the insider elements of our work that we forget to deliver to our clients.

Greg: That’s an important point. Elsewhere there’s pressure to create things that were fashionable and new and could live alongside the work of other people in the industry. Because of the dynamic that we’ve created, we reinforce each other’s work such that I don’t feel that pressure. We don’t need to make work that anyone else would recognize as good, we just need to know that we’re performing the work that we need to perform as a service for our clients and collaborators.

Lulu: We also work pretty fast. We have too much going on, in a good way. We don’t have time to make things really precious and intellectual: it’s just about how well they perform.

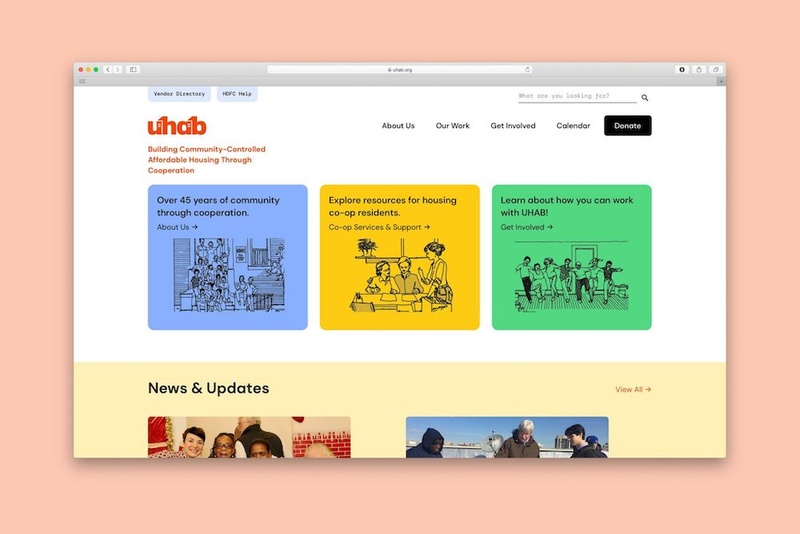

Devika: Like Logan said, this is a service that we’re providing. We often frame our projects as tools: for instance, a website is a digital tool for an organization to organize, to present themselves to the public, and to communicate certain information. Tool building is an important aspect of what we do. It’s not about making the coolest work out there right now.

In terms of taste, what’s really cool about having this melting pot of creative people is that you can see everyone’s taste in our work. But when it comes together on our site, it’s like, oh, that’s Partner & Partners. We all get to exercise our own personal taste.

Greg: No one is passing it down. There’s no Vignelli at the top of our studio saying our work has to look like this.

Devika: Erik and I will work on sketches for a little bit and then we’ll say, do you want to trade? And we’ll work on each other’s directions for a bit. It’s fun because you don’t get bored of your own stuff.

We had to do that in art school! It taught you not to be precious with your own work.

Devika: Yeah!

Erik: I think it’s a key element of our structure; it really feels like most projects pass through all of our hands, and that makes our work feel less precious. It speaks to the overall ethos of the studio: our process is very collaborative.

I’d like to address another socialist ideal that you’ve achieved: the four-day workweek. You guys do so much amazing work in the span of four days.

Greg: We try!

Lulu: It’s really helpful being in the studio for four days of the week because you don’t want to do more work when you get home from the studio on Thursdays. It makes you more productive: you do what you have to do in those four days.

Devika: To be transparent, sometimes we do have to work on Fridays. It’s more like: I have a meeting because it’s the only day that worked, or I didn’t finish some deadline, or I’m gonna follow up with emails. But I still wouldn’t call it a five-day workweek.

It started when I was an intern, Greg was volunteering at Interference Archive on Fridays, and we were the only ones at the office. And you know how it’s like on Fridays—you just want to go home. You take super long lunches.

Greg: No one wants to respond to my email on Fridays, and I don’t want to respond to theirs. So we decided we could be just as productive in four days and it would give us the potential for nearly half of our time back on the weekends. We’ve never looked back.

But we all trust each other. We’re not going to abuse that. If things need to happen on a Friday, they happen.

Does the extra day give you more time to nurture your creative side?

Devika: It should!

Logan: I go on bike rides on Fridays.

Devika: I sleep in and hang out with my cat.

I would argue those are all great ways to connect with your practice.

Greg: You think you’re going to have the energy to sit down and work on self-directed projects, but really you go take care of your laundry, drive upstate, do whatever you need to do to refresh.

Devika: Which is essential.

Lulu: Three day weekends are great. I do one chore day, one rest day, and one social day. I don’t know how I could do without that.

Erik: Can’t go back. Won’t go back.

Devika: The work that we do in our studio already feels like it’s self-directed. If there is a project I wanted to be working on it’s already happening here.

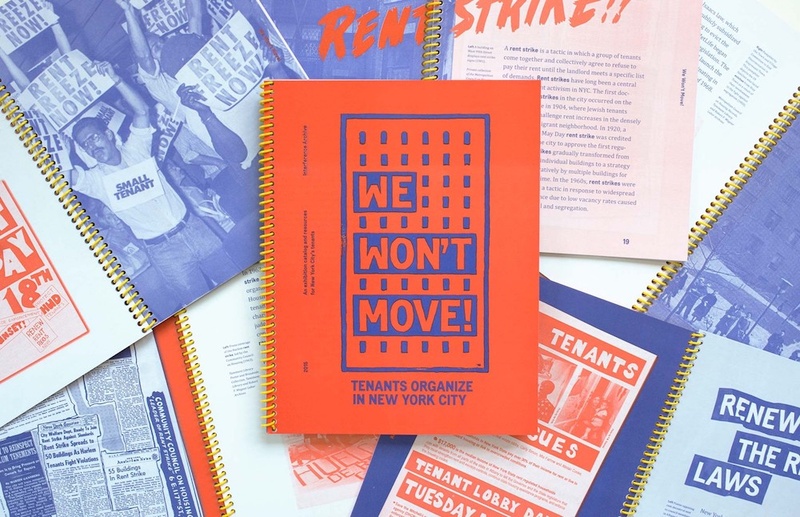

Lulu: Devika and Erik and I were recently asked if all of us had individual practices outside of the studio and we were all like, “no, not really.” But the more I think about it, the more I feel like our joint practice is all of our individual practices. Thinking about Logan, for example—in the fall, he was doing some volunteering for Housing Justice for All, and they asked for something more formal, and he ended up bringing his work through the studio. It seemed the most natural to do it that way.

Devika: And we each have outside interests that are separate from our work, which is nice.

How do you think the industry at large can practice this kind of care and trust? Is there hope for the rest of us?

Erik: I think it’s going to require a different mentality for sure, a shift. I think we’re already seeing signs of that growing, and certainly the pandemic has exacerbated signs of those pre-existing issues with big organizations and top-town structures. I think we’ve all been surprised, since we’ve transitioned, how much work we’re now doing for other co-ops; and that mentality has been around for a really long time, but it really feels like there’s a resurgence coming. I feel like it has some legs now; it’s really starting to take off and get more exposure, which is exciting. So I think it’s definitely within the realm of possibility. But I think more awareness campaigns around it are going to be key.

Greg: And it’s super important that more of the schools that are teaching creatives, and that more of the publications that are featuring creatives, take our orientation and structure into consideration as part of what they hold up as good work. Because if we continue to hold up works that are championed by one person, but that represent and capture a whole bunch of work that is invisibilized, we perpetuate the problem.

If we can ask: Who’s doing this work? Was it equitably produced? Is the client perpetuating bad labor practices or polluting the environment? Why are we continuing to talk about those companies as the best examples of design? If that changes, then more people will be like, “I don’t want to work for a company that treats me like shit. I want to go work for a company that’s taking care of me, and that I feel good at.”

Partners & Partners Recommends:

Staying hydrated with this 24 oz. tall working glass.

@covid_aesthetics for a laugh, or cry.

Climbing your nearest fire tower.

Visiting remote areas of the world via a game of Geoguessr, a P&P pandemic pastime.

Browsing an archive, digitally or physically. We recommend Interference Archive (in person), Free Speech Movement Archives, or OSPAAAL.

- Name

- Partners & Partners

- Vocation

- Design studio

Some Things

Pagination