On working both sides of the professional literary fence

Prelude

Erin Hosier is the author of the memoir Don’t Let Me Down and the co-author of Patty Schemel’s memoir Hit So Hard. She is also a literary agent with Dunow, Carlson & Lerner.

Conversation

On working both sides of the professional literary fence

Writer and literary agent Erin Hosier discusses how she accidentally fell into her current career, the ways in which being a writer better helps her understand what other writers need, and the complications of writing about sexual abuse and unpacking your own past.

As told to Mark Sussman, 2385 words.

Tags: Writing, Process, Mental health, Anxiety, Multi-tasking, Beginnings.

How did you become a literary agent?

I had a really lucky debut into publishing. I simply got the dream job accidentally, working for the person who became my mentor, Betsy Lerner, who is a Jill of all trades. She was an editor, a writer, a poet, and then became a literary agent. She sort of taught me the ropes and she was very into non-fiction, narrative nonfiction, and memoirs.

I was really spoiled, and I just got to work on the things that I loved. We were at a very small company, it was just five of us at the time. And my boss, David Gerner, was like, “Oh, you want to be an agent?” I’d been answering the phones for about a year, and one of the agents left the agency so there was a hole. He was like, “If you’re feeling a project that comes across in the slush pile, we’ll help you do that.”

It was the dream job. I got paid a salary and I made commission on top of that. That was the only game in town like that, because the agency represented blockbuster authors. It just was a lucky, lucky situation. When I left it was because the agency started expanding and my mentor went to start her own agency with somebody I respected in order to keep it small. I was just like, “I’m going to follow her and do what I want.” But I took a big pay cut to do that. “I’m going to choose poverty.” I didn’t know. I think I was selling until 2008, which was when there was that horrible recession. I think I only sold two books that year. It was horrific for me and led to me having to leave the city and go upstate for a while, because I thought it would be less expensive. It was not.

At my job now, I just make commissions, so I have to sell, sell, sell. But I don’t sell. I have a small stable of writers. I take on five new things a year. I just have my repeat customers since I’ve been doing it now almost 20 years, which is so weird.

Once you start working with a writer, and it’s clear they need some guidance, what do you do with them?

Everything. I really pride myself on this. I don’t take that many people on, because I feel like I know what this anxiety is like. I’m going to anticipate every question they have and I’m going to answer it because I think that’s what missing in publishing. This is true of the editorial side and publishers in particular, the way they don’t communicate with writers about what’s going to happen to them and what is expected of them.

Right now everybody in my stable is really, really solid and really good, but there’s a lot of managing of anxiety disorders and depression. It is not unusual for one of our clients to have a nervous breakdown or need our advice about therapists or have a drinking problem and need help. It’s that kind of intimate relationship where you are almost a family member.

When did you realize that you made that turn—from being an agent who offered support to being a writer that needed support?

2017, when I co-wrote [Hole drummer] Patty Schemel’s book, Hit So Hard. But it was really just the nuts and bolts. I had to create the narrative, I had to flesh out the interviews and go into her interior life, try to represent her sense of humor. It took a year. When that came out, I was like, “Oh shit. I can do something on time. That means I’m a professional writer.” There’s a book out there.

Does your sense of yourself as a “professional” change the way you approach writing?

Yes, but in some ways it just helps make clear my limitations. I always wish I was better at it—I wish it would make more money for the publisher, I wish it wouldn’t have taken so long—but with publication comes those rites of passage that make you feel good: receiving endorsements from your peers or critics, receiving letters from readers, being asked to speak in front of a crowd. It’s a confidence booster and makes me feel better equipped to relate to and collaborate with my writer clients.

What about writing your memoir, which must have been basically done by the time your book with Patty Schemel was out?

There were all of these publishing nightmares that happened, the most important of which was that I was a year late turning it in. Usually you have a year to write it. I sold it on proposal. There was a small auction. It was painful to be rejected by peers, but not that bad. Two guys were really solicitous of my writing in the beginning, and then once the book was submitted, it was like radio silence. My agent was like, “I’d just really love to know what you guys are thinking.” I was friends with both of them. A couple of men were like, “She shouldn’t be writing. I don’t get this. I think you need a vagina to appreciate this book.”

Speaking as someone who does not have a vagina, by the way, that’s not true at all.

I definitely spent some years thinking this is only for women.

Do you have a regular writing practice?

I have a constipated writing practice. (Has anyone ever said that before? Seems too obvious.) Everything happens in a burst of guilty confession—even if it’s just an email—and I probably am only motivated to do it because it feels like a job, a deadline. I find that as I get older I don’t need to write like I once did. I’m more than happy to read and sell the work of others. I like to write on a couch with a laptop; a desk is too formal for creativity, even though I’m aware the desk helps prevent naps. Pauses for sleep are essential. Or smoking. Or television. Or skincare routine, laundry, online shopping, nachos, etc. My practice is procrastination.

The memoir focuses on your relationship with your father, but it seems like you must not have started it until well after his death.

Yeah, 10 years after. I was dating and having these really unhealthy or obviously bad romantic endeavors, and at the same time trying to turn them into the greatest love story ever told and realizing, in therapy, that this is rooted in childhood. I believe in Carl Jung. I believe in the collective unconscious and Freudian theories about child development. Repetition compulsion. Once I recognized the concept of repetition compulsion, I immediately associated it with rock and roll, because music is repetition.

What happened was, my father dropped dead of a heart attack. I was grieving for like a year, where you’re in a fog and it’s weird, acting out. I cheated on my longtime boyfriend with a dangerous person who might own a gun, that kind of shit. Obviously I needed help. I was depressed, so I went to a therapist for the first time. Like most people, I was very defensive of the questions about childhood. Were you abused? In what ways? It’s just like when you are grieving a relative or anyone, you’re just seeing them and the loss of it in the best light and through the best memories.

Then a year later, my therapist was like, “You’re fucking clinically depressed, and I can see it.” She sent me to a shrink and I started antidepressants when I was, I think, 27 or almost 28. The first time I dropped a Lexapro, I had almost a psychedelic experience. I could feel it changing me. It only took like two weeks.

But nothing really changed, which is so frustrating. You know how expensive it is. I was angry all the time. I was abusing drugs. I was lying and, I think, hurting myself but also hurting other people. I hated myself. I was just like, “Shit.” At that time, Mad Men was a phenomenon, and I saw myself in Sally Draper. Of course, I’d been kind of workshopping the book without knowing it.

The impetus of Don’t Let Me Down is the image of my father in his tighty whities, catching me in bed with my boyfriend when I was 16 years old. The jig was up, because the whole town knew about it. But I wasn’t losing my virginity.

It was like the public loss of your virginity.

It was so traumatizing. I also saw it as high comedy. I’ve heard comedians talk about that eternal shame. I must have written the scene, and Betsy Lerner was just like, “You need to write.” I was a very good email writer and essay-istic writer and I’d written a couple of things that went semi-viral within publishing. Then, I don’t know, it was like a lucky moment I guess, people were buying memoirs. I wrote a good proposal that had the title, had the epigraph, and included my brother’s sexual assault as a child. That was essential. That chapter is called “Don’t Let Me Down,” and that was the essential trauma in the family or, in my view, of what parents are there for, fathers.

How did you deal with the realization that you were going to have to write about your brother’s sexual assault?

I had a panic attack at my desk at work. I emailed Betsy, who was sitting like one cube over. I was like, “I’m having a panic attack. I’m about to jump off the boat. Let’s go outside.” We quietly went outside and had a cigarette and I told her the story. At that point, she’d been my close friend, but I just didn’t talk about that story. I realized I can’t not explain that because it’s the central guilt of my life is that I didn’t protect my brother. Even my father, when it was exposed that we lived next door to a pedophile, did not do anything. None of the adults did anything.

At some point, you had to tell your family that you were writing about your brother’s rape and your father’s emotional and physical abuse. How did you broach the subject?

It took me a year to tell my mother. And when I did, it was in the midst of a breakdown. I knew I had to tell them, because I knew I had to write about it if I was going to write about the truth and the source of all my anxiety or neuroses. It was during a phone call with my mother. I don’t know what I was expecting, but she absolved me and, of course, had the proper reaction of being like, “Oh my God. I’m so sorry.” She wasn’t surprised. She wasn’t condemning.

Then when I told my brother, Greg, the victim, he knew that I was writing about him. He had given me express permission, and I interviewed him about certain memories. He was clarifying. It’s sad, but I think for him, he knows or believes, as most victims do, that it’s such a common thing. But when you’re unlucky enough for it to happen to you, it’s brutal to live with.

One of the things I love about the book is how you’re able to reconstruct your mindset from earlier in your life. But of course you’re writing with the sophistication of your present self. How did you create that balance?

I interviewed my family members, particularly my mother, and talked about their memories of specific events and their general impressions of family life, and let that inform me (especially regarding the things that were happening behind the scenes in my parents’ marriage). But I was careful when I was writing the first half of the book—about childhood and coming of age—to only write using the information that I had at the time of whatever action is taking place. So the more suspenseful scenes in the book are experienced by the reader as I experienced them in real time. I knew I wanted to express the fear and confusion (and also peace and love) that a young person experiences as they are consistently disillusioned by the adults in their life, and by life itself.

Is there any relationship between the support you offer your clients in your work as an agent and how you approached writing the memoir?

I think I have to feel like I’m helping people in some way every day, just as a rule. I did think about the concept of “triggers” for the reader when I was writing about sexual assault, but ultimately I think that was me responding to my own fears of overexposure, hoping abuse wasn’t a key aspect of the story. But of course it was. What motivates me now is socio-political change. I want the next generation of American parents to do things differently, to stop the cycle of state and culturally-enabled violence and acknowledge that the way you raise your kids will have a forever-impact on the way they view the world. I want change when it comes to the statute of limitations for reporting child sexual abuse, for instance, and harsher penalties for abusers. And a societal investment in mental and behavioral health, as well as an investigation into why domestic abuse perpetuates itself, and how we can prevent it from happening.

Erin Hosier Recommends:

Vaccinations, insect repellents containing Deet, and chemical sunscreens with a high SPF. Don’t come at me with your herbal lies.

If you’re going to come at me with herbal truth, however, and happen to be in a state where it’s legal, I recommend the strain Blue Diamond.

For those who are grieving or love someone who is, I’ve found Joan Cacciatore’s Bearing the Unbearable to be incredibly comforting and helpful. We need to change the way we talk—and don’t talk—about death and its aftermath.

The Breeders’ 1990 cover of “Happiness is a Warm Gun,” because Pod is a perfect record.

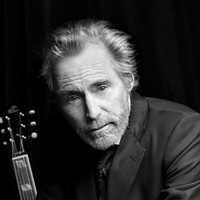

- Name

- Erin Hosier

- Vocation

- Writer, Literary Agent

Some Things

Pagination