On making space for creativity

Prelude

Marian Bull is a writer, editor, and ceramicist living in Brooklyn, NY. She writes a weekly cooking newsletter called MESS HALL, and is at work on her first book.

Conversation

On making space for creativity

Writer and ceramicist Marian Bull discusses learning where to place your energy and balance your interests.

As told to Grashina Gabelmann, 2621 words.

Tags: Writing, Editing, Art, Process, Day jobs, Money, Mental health, Time management.

What is your creative practice?

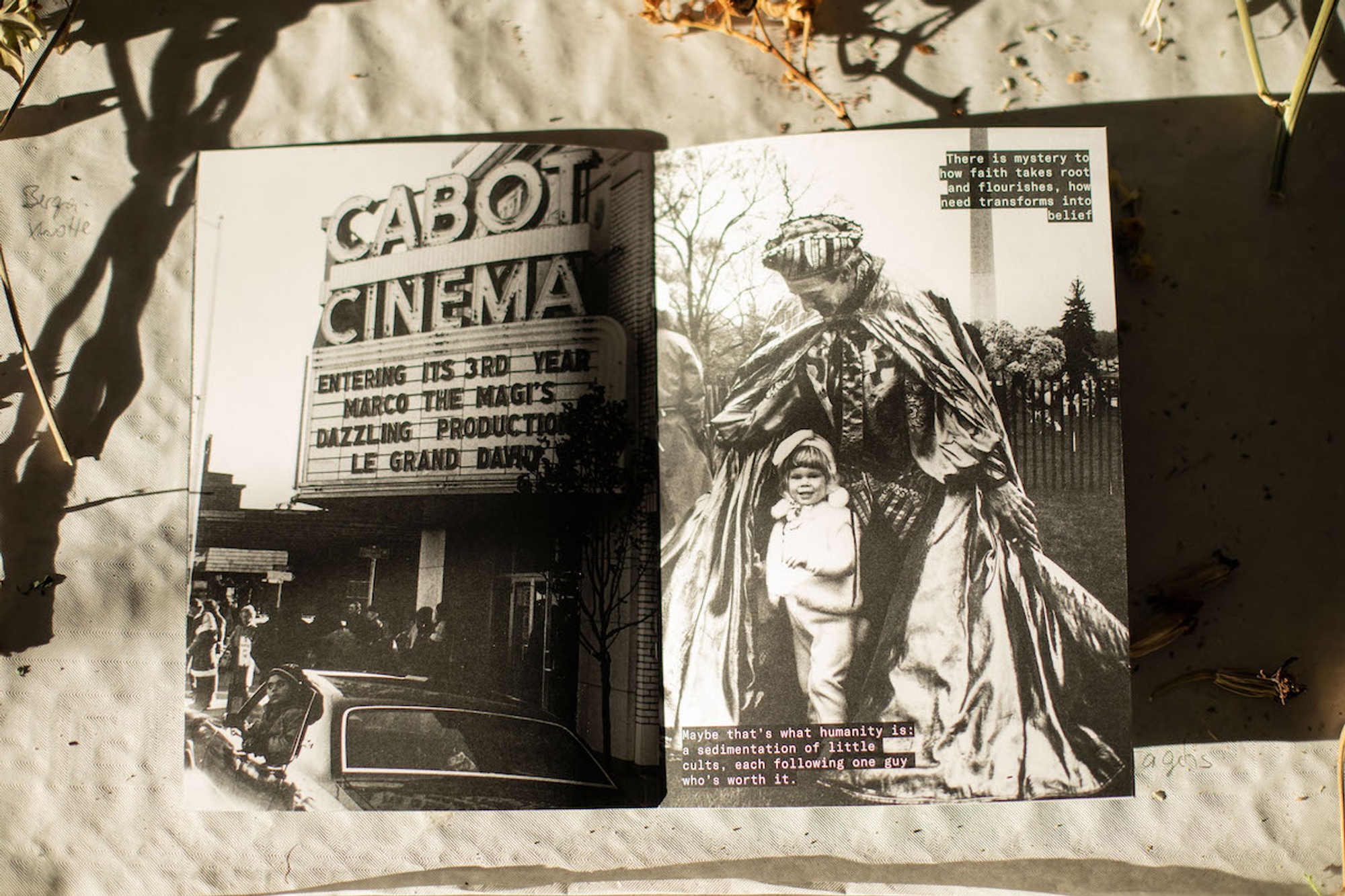

My creative practice is generally divided into two buckets: writing and ceramics. I’ve been writing professionally for 10 years now—my background is in food writing—and I’ve been making ceramics for seven years. I am also writing a book about the stage magic company that I grew up in, which is part memoir and part oral history project. So a big part of my creative practice is figuring out where the energy is going on a given day and how to balance the different interests, obligations, desires, hopes, and dreams that I have.

So how do you go about to trying to achieve a balance or to move the energy around to where you want it?

The nice thing about being a freelancer is that I can adjust how much energy I’m giving to each thing on a week by week or month by month basis, depending on what work is coming in. So right now, I’m in a period where I haven’t really been at my ceramics studio much because I’ve been more focused on writing: there’s the book, there’s my cooking newsletter, there’s a bunch of other writing and copywriting work that pays the bills. It’s quite easy for me to worry about the fact that I’m not at the studio a lot right now, but I think the healthy thing is to respond honestly to your own creative energy.

photo by Camilo Pachón

But a lot of the times there’s also just a need to prioritize work that pays right?

Yeah, that’s a very real factor in the equation. Every month I need a certain amount of “money work.” Once I’ve done that, I try to fill the rest of my time with work that I care about. And then I have to carve out some empty space for myself. I believe creative thought happens when your brain has the space for it. When it has space to be idle and the space to float around in new directions, even if it’s just 20 minutes a day. I think that’s one thing that artist residencies have really taught me: how to build space for yourself that will allow your brain to go to new places, or make new connections.

Can you tell me more about that?

At residencies, your primary purpose is to just make the work. This has taught me the importance of building out time and space for your brain to not have to focus on anything that’s too productivity-oriented. Whether it’s laying down on the ground—an important creative practice—or going for a walk, seeing art, cooking something new. I think having idle time is just as important to build into your life as saying, “Okay, I need to spend one to two hours every morning writing my book.”

photo by Matt Martin

I’ve also been at art residencies and I was confronted with being goal orientated and other habits. There’s this hope that as soon as you’re at an art residency you’ll immediately be creative. What has you’re experience been like?

I love residencies. They’ve been very crucial to me as somebody who has been working on a book without a book deal yet. I’m just working on it in these small pockets of time I’m able to carve out.

I do think the reality of a residency is always different from the idealized version of a residency, but I still think that it is a lot easier to attempt new creative patterns for yourself there because you’re not constrained by the patterns of your existing life, whether that’s social, professional, romantic, familial. At a residency I think of myself as a very social monk.

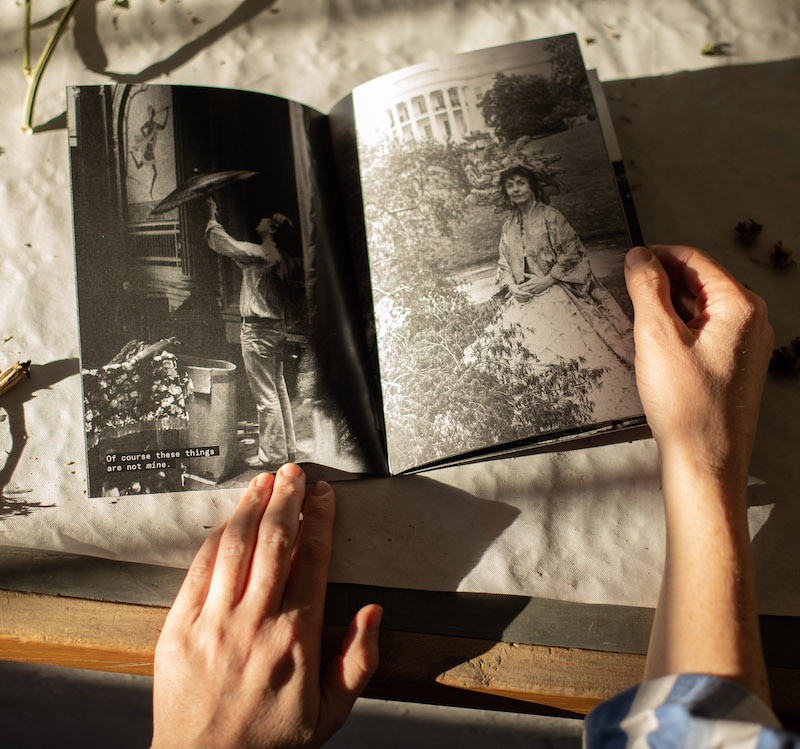

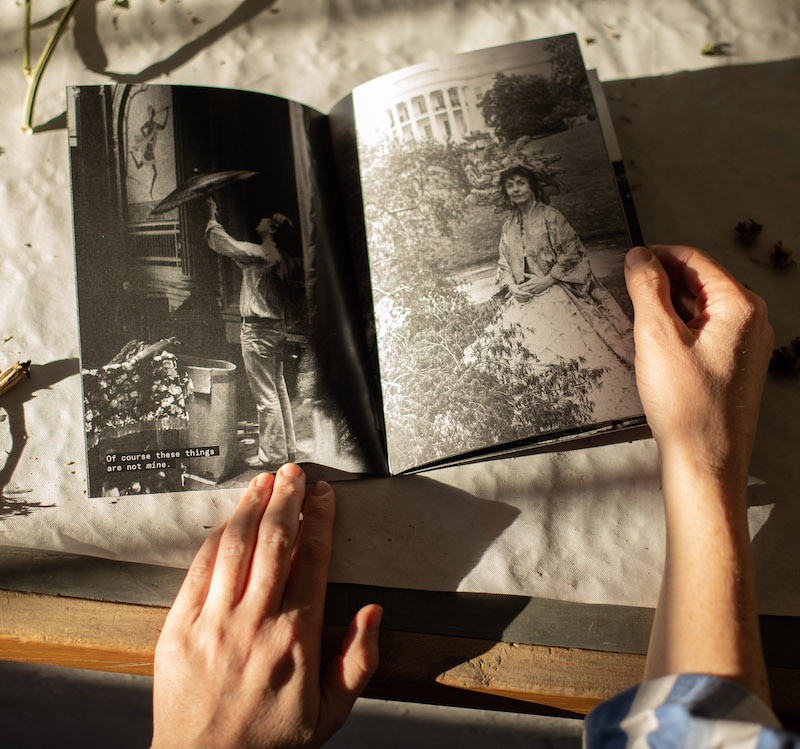

So I think it takes a significant amount of effort to establish the habits that you want to establish at a residency. But I do think it is much more doable than it is at home. I think that it is a really great opportunity to try things out, whether that’s trying out different ways to structure your time, or trying out different projects, because I think it is a space that encourages inefficiency. When I was at a residency in Germany last year, I put together this zine that I had been ruminating on for a while that used archival photos from the magic show, collaged with text. I had the space to just dedicate two weeks to trying to put together this thing that had no purpose other than I wanted to do it. It was an incredibly useful creative exercise in that it allowed me to pursue a feeling before anything else. With that project, knowing immediately that I wasn’t going to try to exchange it for money was very important. As somebody who has a bad habit of turning their hobbies into revenue streams, there’s something incredibly freeing about insisting on not selling something. It also makes sharing it with someone else more meaningful. It is a completely different social, emotional and psychological experience to share something because you want to, instead of turning it into a commercial product. I think refusing to sell it meant that my goal was to create something that evoked a certain feeling in me before worrying about how it was going to make other people feel.

photo by Camilo Pachón

You said you have a bad habit of turning hobbies into jobs. You started ceramics for fun and now you sell your work. Would you say, looking back, you regret doing that?

I’m not sure I would call it regret because ceramics is an expensive hobby, and so selling things meant that I could commit more time to it, which I really wanted to do. So it was a pragmatic choice, and I understand why I made it. Sometimes I see older pieces of mine that people bought, and I sort of cringe. But there’s also a looseness to the early work that I appreciate. A lot of my ceramic work over the last couple of years has been driven in part by whether I think I’ll be able to make money off of it. This is out of necessity: studio rent is expensive and so are materials and so is living in New York. But last fall, I realized that I had burned myself out because I was just trying to sell as much as I could, which is not a particularly gratifying creative goal. I had a great year financially, but I also learned that that level of production is too much for me, both physically, mentally, and logistically. The past few months I’ve shifted my schedule a little bit such that I can spend a little more time at the studio focused on playing around and having fun and experimenting. Because if I’m not doing that, I don’t think there’s any point to it. It’s important to make ugly stuff, to make mistakes, to fuck around. You usually learn more from an ugly piece than you do from a beautiful one. And making things for myself is often the best creative prompt in the studio, because it means my work is driven by desire and dreaming, not pragmatism.

photo by Matt Martin

How were you able to make that shift?

Well, the nice thing is that on an hourly basis, writing is more profitable. So if I spend more time building the newsletter, and getting other paid work, then all I really have to worry about is breaking even at the studio. Right now I’m only there 5 to 10 hours a week, rather than like 20. That will change soon—I’ll get back into production mode and focus on making money again, but I really am feeling the need for a reset. The nice thing about having created this flexible profession for myself is that if I need to find a little bit of work over here, I can. If I need to find a little bit of work over there, I can. Living in New York is insane, but it has also allowed me to develop a pretty rich professional network.

You’ve done a few residencies. What can you share about experiences you’ve had that could be helpful for others?

I often struggle with not being disappointed in my own productivity. Obviously, productivity is this fucked up concept, this awful capitalistic concept. I think it’s important to have at least one idea of what you want to do when you go to a residency, which you often need to state in your application anyway. But it’s important to keep your goals simple, and let them be flexible. The whole point is just being there and making an effort and being open to what it’s going to bring you.

Where was your first residency?

My first residency was at 100 WEST in Corsicana, Texas. One of the other residents there, Tom Holmes, told me something I always think about, which is, “A lot of times, the work you do at one residency doesn’t show up until the next residency.” So I do think that it’s important to remember that a lot of what’s happening to you at a residency is the kind of stuff that you might not notice immediately and might not immediately affect your work, but will affect your work in the future. It’s essentially fertilizer. But the experience can still be stressful and annoying and difficult and painful and all of these things. You’re not spending a month in paradise. You’re still inside your brain.

photo by Camilo Pachón

Another piece of advice I got before I did my first residency came from my friend Dayna Tortorici, who’s a brilliant writer. She said that at her residency, “Every day I clocked out at 5:45, and I tried to gorge on beauty.” You know, maximize your aesthetic inputs. Inputs obviously feed the outputs. I think that when you’re a self-employed artist and you’re preoccupied with just doing the work that’s going to pay your bills, it can be really, really easy to deprioritize those inputs and the space required to metabolize them. But if I’m absorbing good art, it helps my work. If I’m scrolling all day, I can feel the work suffer.

The book you’re writing about the magic company your family was part of, you said you don’t have a publisher at the moment. So does the book feel more like a creative outlet than work to you?

Yeah, that’s a good question. It feels like work because it’s hard and because there’s always something to be done. I’m not just writing, but I’m interviewing dozens of people, and working deeply in the interview transcripts. I’ve gotten really into oral history as a methodology and a practice, because it’s a radical shift from the “journalist-subject” dynamic I’m used to. It’s all about prioritizing the reality of the interviewee, and complicating the idea of “truth” as some fixed thing.

Logistically, the book is an enormous undertaking, and that can feel overwhelming and can make it really feel like work. On the larger scale, it feels like something much more meaningful and expansive than that, because I feel like I am, as much as I can be, in control of it. I think that there have been really practical reasons that I haven’t tried to sell the book yet, in part because I’m still figuring out what the structure, format, tone, and even content of the book will be. There are a lot of different narratives that exist within the story of this magic company that my family was a part of, and I’m still figuring out how they might coexist in book form. I don’t want other people touching it before I have a strong sense of what it will be.

I really did not want to sell one version of a book and then realize I wanted to write a different version of the book and then either have to negotiate that with the publisher, give the money back, or suck it up and produce something that I didn’t want to produce. But another side of the not selling it is that I think the only way for me to take pride in this book and this project is to not be in a hurry. The publishing industry is predicated on deadlines by necessity, and I am not yet ready to have any serious deadline on this project because it is just completely necessary for me to not be in a hurry. I think that the biggest gifts you can give yourself as a creative person are time and focus. And building your own creative life is basically figuring out how to logistically get yourself as much of those things as you can while still paying your bills, which is no small task. But I just feel so deeply that this book is something that I need to do, and it’s something that I need to do slowly, especially as somebody who is a really fast worker and a really fast writer,. After 3 years of very intermittent work I have like 30 pages of a draft, plus a whole lot of mess. It’s slow. As somebody who is constantly switching focus between 10 different freelance projects, it feels good and necessary to just allow the thing to take the time that it needs.

Yeah. I think it’s also really brave that you go out there and do a huge task like writing a book on your own before finding a publisher because you know you need that freedom.

To be clear, I do plan on selling it. Maybe next year I will be ready to write a book proposal. But I need to get to a place where I feel confident about what this thing is going to be before I can try to sell it. I think a lot of people are really conceptual thinkers, and I am not, and I need to work through something for a while in order to figure out what I want it to be or how I feel about it.

It’s like the Joan Didion quote, “I don’t know what I think until I write it down.” One thing I’ve really had to learn about myself as a freelancer is I’m not going to have these fully formed ideas in my head all the time. I just have to work through them, and then I will figure them out. It often means sitting down with a fragment of an idea, or even just a feeling, and seeing where it takes me, rather than sitting down with a plan of what I’m going to write. I think that’s a big part of the slow process of this book, is that I just knew that I had to toil at it for a couple of years before I even had a glimmer of what it was going to be.

Marian Bull:

Giving gifts outside of birthdays and traditional gifting holidays

Leonora Carrington’s *The Hearing Trumpet

Beverly Glenn Copeland’s Live at Le Guess Who?

Falling into a hole of Joseph Cornell’s work: his boxes, his short films (pre-fancam fancams), his habit of keeping entire, frosted chocolate cakes in his fridge that he refused to share

Michael Twitty’s The Cooking Gene

- Name

- Marian Bull

- Vocation

- writer, editor, ceramicist

Some Things

Pagination