On becoming an artist by listening

Prelude

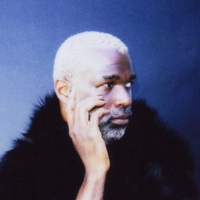

A. Kendra Greene is a writer and book artist. She is the author and illustrator of No Less Strange or Wonderful: Essays In Curiosity (Tin House), and The Museum of Whales You Will Never See (Penguin Random House). Her work has come into being with fellowships from Fulbright, MacDowell, Yaddo, Dobie Paisano, and the Library Innovation Lab at Harvard.

Conversation

On becoming an artist by listening

Writer and illustrator A. Kendra Greene discusses the power of noticing, collecting fascinations, and letting curiosity guide your process.

As told to Katherine Cusumano, 2320 words.

Tags: Writing, Art, Inspiration, Process, Education, Collaboration, Multi-tasking.

In your bio you write: “She became an essayist during a Fulbright in South Korea while she was supposed to be making photographs.” Could you tell me more about how you started writing essays?

I’m not one of those writers that always knew this was the thing. I knew early on that I loved conversation, and I’ve always been fascinated by the mail. I mean, it’s really sort of a miracle, the entire postal system. I was writing letters home, both on the coolest stationery I could find and over email in internet cafes or at work—trying to keep up with everyone I knew. The copying and pasting, the gradual organic expansion of how I was thinking about audience and telling stories, meant that by the time I got back home again, I was an essayist.

At what point did you start thinking of those letters as essays?

I think by the end. I mean, the photographs were in trouble for all sorts of reasons. It was hard to get darkroom space, it was hard to order the right supplies. I felt very earnestly like I could not be confident that I had permission to take pictures. There’s something about photographs—I know other photographers can do this, but I couldn’t see how to make them shake off the authority of document. It felt like they inevitably said, “This is how it is.” And I did not have the authority to say “This is how it is.” It always felt like hearsay and a tenuous grip on what I was encountering. But the letters had all the space for nuance and caveat and doubt.

When you look at the history of documentary or the history of photography, when photographs or films were put in front of people and they didn’t really understand them as well as modes of representation, they were taken as authoritative. People were like, “This is objective truth.”

Getting to illustrate my first book, The Museum of Whales You Will Never See, sent me on a deep dive in thinking about what nonfiction text and image could possibly mean. I’ve got a background in photography, of course, but at this point I feel like the Japanese fish print art of gyotaku is maybe the best metaphor for the essay. You have to encounter the world in order to make this art, but that art also has the imprint and the artifact of all of the choices you made to try to record that encounter.

Your second collection, No Less Strange or Wonderful, also contains your illustrations, as well as archival art. At what point in writing do you start to think about the role of the image?

The language is usually first. For this book, I spent a month in special collections understanding, how have we been doing this for centuries? How have we been thinking about the natural world in text and image? A bunch of books, I couldn’t read because of the language of origin or how archaic the text was—but I could still read how the text and the image interact on the page, how you encounter them, how you present them.

A poet asked me to illustrate a book, and I realized I don’t think I’m an illustrator—I think I’m a bookmaker. I didn’t know how to approach making the images until we knew something about our options for page size and text block and the type of paper. The materiality of it mattered. I’m convinced that part of what makes literature so magical is that it inherits two of the most remarkable human capacities and expressions there are: It sits in the oral tradition and in mark-making. Writing is always embodied, either in a body — through the storyteller — or on the page, on the screen. So I think there’s a very natural extension from the characters that render text to other forms of mark making.

In an interview in 2020, you described essaying, kind of like visiting a museum, as an exercise in paying attention. Do you still feel that way? How do you train that kind of attention?

Amen. I think attending is one of the most beautiful, important, necessary things that we do—giving our presence of mind to something and staying with it. I think a lot of what I do is paying attention to something for longer than it’s normally paid attention to. You start taking seriously things that often aren’t. It’s not hard; anyone can do this. There is so much in the world and a finite amount of time in which to examine it. You start researching, and you go from knowing nothing to kind of being an expert in this shockingly short amount of time. Most of the world, most people, most things, most everything is not paid enough attention. I think I got to become an artist because I finally found something that had a way of thinking about art as a matter of listening and not a matter of having something to say.

One of the things that really struck me in the book is it does seem very attuned to the strangeness, weirdness, wonder of very mundane situations. Do you start to recognize in the moment, “oh, this might be an essay,” or does it start to come together later? How does that influence your process of documenting those encounters?

I think what I noticed first is what I love, what resonates, what I’m fascinated by. And you just keep collecting those things and they start to talk to each other. They start to be in conversation. I think about all of the gifts that are just waiting in the research, all of the parallels and connections and resonances. Part of that is obviously coincidence, but part of it isn’t. Language is always a tool of trying to map, and we will use the language to talk about a bunch of different things that have some relationship.

No Less Strange is coming out five years after your first collection. How do you sustain your attention on one project over five years? What else are you doing to complement that work?

When I’d finished the manuscript for the Icelandic book, but before it sold, I’d started work on the next project, The Poison Cabinet. Then the Icelandic book got picked up, and we did the things for that. It was getting ready to come out in the world. I had all my research appointments set up for March of 2020. I was going to the National Library of Medicine, for a project that’s very much about what we hold in collections. It was a bunch of site-specific research; the materiality was inescapable.

And suddenly, I was a travel writer that was grounded. It gave room for this project to start asserting itself. I’d been thinking from there about bestiaries and how they function, the way they allow for a kind of wild, motley, experimental collaging of knowledge and fact and maybe-fact. Virginia Woolf, in a letter about Orlando, describes it as shoving everything aside to come into existence. She talks about the idea of a writer’s holiday: That after a big project, you have this space—not to stop writing, but to make a thing for no purpose, that no one wants, that no one is asking for, because it’s the thing you want to do. And so it was actually the first time in my life where I’d really consciously been working on two projects. There’s sort of a nice procrastination effect; one of them is always easier than the other, so there’s always something to do. Did you know that if you have a really nervous racehorse, you can give it a goat buddy? So I was thinking about this big thing I thought I was concentrating on, and this sort of wilder thing showed up.

That’s your goat buddy.

The bestiary is obviously the goat buddy, keeping the horse company and maybe making it better and evening it out.

What does your day-to-day writing routine look like?

I love the idea of routine, and it doesn’t capture what my writing needs to do, is the short answer. Probably because it makes you start to have to define, what is the writing? Does the research count? Does reading stuff that you don’t know if it’s related count? Do the long walks count? Does talking to a friend to work things out, or they say something really smart or you get new purchase on it? I actually find it really hard to define what the writing is, in part because I built it into my life so that it is part of how I do everything. The paying attention, the being curious. When I got out of grad school, I thought, “all right, I’m going to be one of those write-first-thing-in-the-morning writers,” and I would fall asleep at my desk. It was not the answer. I also know that there is a particular sort of grumpiness, which is a sign that I need to actually be on the page—that there’s something that needs to be tapped or I will continue to be a little bit agitated.

One of the things that I found really exciting about No Less Strange is that it seems like your own interest in things that maybe go unnoticed in everyday life is the engine of some of the essays. These essays end up revealing how much strangeness there is in the world, if we could only be attuned to that—to get back to your point about attention. How do you approach animating things that don’t immediately lend themselves immediately to narrative?

I remember as a philosophy major really falling for Heraclitus and the idea of fragments. They’re sort of marvelous. The section break is one of my favorite friends, right up there with “and” and the comma. You can start again and again; you can introduce white space or a pause that breathes its own meaning into things. The world is not linear or causal or built on hierarchy. We tend to encounter writing as a linear form, and how to negotiate that, how to keep it from asserting something that isn’t true, is a real issue. I sometimes feel like a plate-spinner: I need you to know 12 things, but I need you to know them all at the same time. It’s not about the domino of one to the next. It is about how they sing when they’re all together—that’s what I am trying to give you.

I think about the writing advice to “murder your darlings.” For the people for whom considering preciousness is useful, whatever tools let you do the work you need to do, power to you. But I feel like my approach is very much “smuggle in all the darlings you can.” In The Nutcracker, there’s the dancer on stilts who has the giant skirt full of children. I feel like there’s a sort of scooping in: “Come with me if you want to live; we’ve got room for you too, probably.” I think, if it matters to me, if I keep thinking about it, it means something, and I should probably work harder to give it a home.

That’s the collector’s instinct too, I think.

Mm-hmm. “You have a place, let’s figure out what it is, and what happens because you are together with things that are or are not obviously similar, because it’s going to be great both ways.” The amassing, the amplification is powerful, and the discord, the disjunctures — my goodness, there’s power in that too. Everything good happens because of friction or flow.

A. Kendra Greene recommends five chance encounters:

The possibility, at best now remote, of that perfect Blommer’s chocolate smell taking you fully by surprise, at any time, somewhere in Chicago, independent of geography or weather or time of day.

The cardamom pistachio morning bun that The Beet Box had the first time I went there, on Friday, so good I saved the last bite to share with another witness, and already gone when we went back the next day, out of rotation again for who knows how long.

The sea monsters in the gift shop of the Icelandic Center for Sea Monster Studies, knit by someone in town who doesn’t leave her signature on these marvels, stopped making them a few years ago in fact, the thick yarn not rough but so textured in the hand, little amber disks on tiny loops jauntily invoking the clatter of seashells one might find on the sides of the shore laddie.

The sight of all these mantises! A gift of the algorithm I pass on to my dearest observer friends, the shock of nature in such exquisite fancy dress still a kind of disappearing act, more stunning than the thing it might have meant to mimic.

The speculative soundscape of what the disputedly extinct ivory-billed woodpecker and its sweet little toy trumpet eeepmight have sounded like in context of other living things. And on its heels, to sneak one more darling in, the only document I can point to of one of my favorite things: the not-poem essay “Things I Have Done While Singing on Stage” by Lisa Huffaker, which exists here, podcast as field recording, starting at 51:29.

- Name

- A. Kendra Greene

- Vocation

- writer, illustrator

Some Things

Pagination