On believing in yourself and your vision

Prelude

TANAÏS is the author of In Sensorium, and the critically acclaimed novel Bright Lines, which was a finalist for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize, the Edmund White Debut Fiction Award, and the Brooklyn Eagles Literary Prize. They are the recipient of residencies at MacDowell, Tin House, and Djerassi. An independent perfumer, their fragrance, beauty and design studio TANAÏS is based in New York City. Follow them on Instagram at @studiotanais.

Conversation

On believing in yourself and your vision

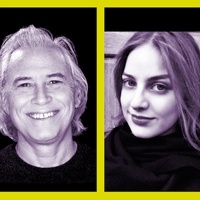

Author and perfumer TANAÏS on writing yourself into the record, pushing back against the publishing industry, fostering new meanings of success, and decolonizing beauty.

As told to Resham Mantri, 3427 words.

Tags: Writing, Scent, Identity, Money, Mental health, Process.

A passage in your book, In Sensorium, begins with your father’s question, “Would I always write about Desi queers? Yes, I told him, I want to write people I never grew up reading, people like me. Writing outside of the dominant culture feels this way, a constant pull towards trying to name and locate ourselves in a milieu that never imagined us. We reach for our futures at the same time we reach to the past, trying to figure out how we got here.” So for you, how much of your writing and imagery serves to write yourself into history or into the records?

I think brown skinned femme embodiment is very unnerving for people. And it makes them uncomfortable when the actual person is describing what they’ve survived, the ways in which they feel beautiful or proud, the things that they have accomplished, and the labor that they’ve done.

Honestly, as I embarked on this journey, the phrase, I am the first of my kind, started to feel so wrong. Because I realized there were these foremothers writing for the liberation of India, which we are no longer a part of, in 1905. And just knowing that, is to be held by something deeper and older than what I am doing. So to me, that constant feeling of, “Is my brown, wild, free embodiment too much to translate into literature?” And the answer is “no,” it is exactly the stuff that literature is made of. I feel like that’s what I wanted to put into the record from my point of view. These different ways of being and seeing the world have built the cultures that are now dominant cultures, even though they are not recognized by that.

We’re othered from a very young age in a way that’s pretty helpful in terms of thinking outside of all of these constructs. As a Brown queer femme writer, what has this process been like for you within American publishing or the writer community?

I think that community building is really important and I think it’s also equally as important to distinguish your own voice and your own mind from that community. I think there’s a lot of emphasis placed on literary citizenship, which is in the most simple definition, “do unto others as you would have them do unto you.” You give and you take and you offer help and you pick other people up; you’re just in an ecosystem. This book is questioning what it even means to be a citizen or to belong to anything. I belong to many things and I feel like what I started to become very aware of is how other minds and other writers’ opinions, and the way that I would feel my energy was being drawn from me was actually affecting my own work.

I think something recently that just happened was I wasn’t on a list of women writers. I use they/them pronouns. And the person didn’t think I identified as a woman anymore because I am asserting myself as femme with they/them pronouns. To me, that is returning to my truest Bangla, pre-English femme divine self. But when it’s translated into American fiction, letters, or literature, it doesn’t translate. And then I’m erased from something where I’m like, “Well, don’t women want to read my book? Don’t women need to read my book? Don’t I love women? Isn’t everything I do for women and femmes?” So I don’t know that the language and the culture has caught up to what actually is embodied. We’re always trying to find touch points where those things meet and intersect. But people are living these vast lives and then language and the culture around us is trying to catch up to the vastness of our experience.

I love that you write the stories of your queer dating life within marriage. Just speaking non-monogamy as a queer South Asian Bangla person is a force. You write about relationships gone wrong, men who disappeared, who could not say true things and relied on you to do this work for them. These are things we as femmes are supposed to get over, be silent about, not speak of. They are in your book next to partition, wars, and Bangladeshi rice fields. How much of this not “knowing any other way to be” informs your art of speaking? What does it take or cost you if anything?

To write it free is a deep privilege because I am not under threat of someone attacking me, annihilating me, and exiling me or imprisoning me. So I acknowledge that first and foremost to all the people who have been killed for having thoughts, including my people. So I feel like the legacy of thought, which has so often been denied to femmes and women of color and just colonized people’s, people in the Global South. I feel called to speak the truth because I have this protection and being enveloped in a way and a path forward through these thoughts that I have. If I don’t speak those thoughts, if I don’t make this a reality, then how can these shifts happen in consciousness? And that is part of being an artist, is really believing in this megalomaniacal vision that you have of the world and being like, this is really what needs to be said, and you fucking say it.

At the same time, do I feel like I’ve been given institutional access and support and financial help and mentors? No, I actually don’t have that many people that I can say have given me those sorts of things, except in the year that I created In Sensorium I had the opportunity to go on three different residencies. What does it take to talk about survivors of war and also being like, I want to fuck this person who’s not my life partner? Why do those things coexist in the narrative?

Well, they’re about freedom, they’re about the wildness of femme bodies and how they trouble people, and the way that the feminine troubles and disorient and is also what nations are fought in the name of—the battleground of bodies that we didn’t even ask to be a part of this mess, these men’s mess. I’m very invested in always seeing how everything is relevant to the smallest choices we make. In those small choices, there are eons of people who sacrificed something to give me that choice. And within our own family, we are all descendants of grandmothers who are child brides, some of us mothers who are child brides. And going back further than that, all child brides. So what does this ancestral trauma of child marriage and rape do to our psyche of people who reject that and don’t have to live that and have the privilege of not living that? We’re still descendants of that.

My grandmother died and I was like, “Oh my god. Look at the beauty of her life and the pain of her life.” And I’m not going to let any person, whether they’re white or upper caste tell me that her story and our story is not as important because it’s been said already. It’s like, no, there is enough room for everybody to keep saying this shit. I reject the narrative that’s like, there can only be one voice. A lot of people have been saying that we need to have more seats at the table or whatever. And I’m just like, “I don’t want to be at this table, I don’t want to be sitting in this stuffy little room with people I have to make small talk with.” I just want to say what I fucking think and hope it resonates.

It’s pretty powerful and moving to read books by those who are the first generation to even have that freedom to speak these things. There’s not enough people writing these stories for me, personally.

Well, there’s not enough of us maybe writing the messiness in sex and falling apart. In the ’90s, Indian literature was blowing up. And that was where I was looking for the narratives, but I’m not in any of those narratives. I think the first Bangladeshi people I ever read were in Zadie Smith’s White Teeth. They were British Bangla people. A quote that I read from Zia Haider Rahman about that book was: “Conspicuously absent from White Teeth is the anger.” I think for me, rage is a clarifying force. You can feel the book pulsing with my rage, it’s right there.

We’re still celebrating books like White Tiger written by upper caste men about savage dull people. So I’m just like, people praise things that I’m like, “What? My community and friends don’t fucking want to read this shit, this is really troubling.” So to me seeing that femme Brown bodied rage and sexuality, I want more of that every day.

In describing perfumery, you talk about the limitations of the language that you’re using to even talk about the sense of smell. This acknowledgement of the limitations of language written by you, this Bangla, queer, femme, American writer in English. There are so many moments in your online persona and in the book where you examine the form itself, the industry itself, the challenges to breaking into perfumery. There are a lot of people right now making this art and also struggling with the real valid critiques of those industries and spaces that they find themselves in. How do you survive it? What do you do?

So I write as a fiction writer first and foremost, and that changed. The reason that changed is because I could not sell the novel that I wrote about a mother and daughter who are separated for many years and the daughter only reconnects with her mother as an artificial intelligence after her mother has passed. That book, which I think in my mind was prescient for the time we live in, did not resonate with the industry. And that caused me to spiral emotionally in a way that I was not prepared for.

The book that people were interested in was In Sensorium, which was essentially fragments of ideas and scraps of essays and not fully formed in my mind. The people who wanted that book and the novel were all young women of color with little power in the publishing industry. So for me, I had to reframe everything again and go back to my roots, which is community organizer, youth educator, working with young women of color, femmes of color, queer people of color in New York City. And these are the people who still have my fucking back as I’m trying to break into this industry again, even though I’ve already broken into this industry with my first novel. But this industry is resistant to change and vision and risk. It’s the soft arm of white supremacy. And I reject that with my entire being. And to be false, to be in service of that at the expense of my own life and my own livelihood and my own writing, never going to fucking happen.

And as I started to write pieces of In Sensorium, I started to send things to different editors at publications. And they literally would say things like, “This is nice, but what’s the takeaway? What’s the point?” And I, again incensed by this ignorance and limitation of the industry, was like, “How do you not see the point of my life? How do you not see the point of my point of view that can help so many people feel validated in their existence on this planet? To me, this industry is begging for someone to critique it who actually doesn’t give a shit about money, awards, prizes. Because I am not writing in service of those things, I’m writing in service of the vision that I have for the planet, for liberation.

That uncomfortable liminal space is where I try to have the conversation of, this is my life, these are the problems that I feel are happening in the beauty industry and the literary industry, this my truth. And at the same time, I am still a part of these industries trying to get my work out there. That place that we’re like, “Oh, capitalism, it’s killing us.” It is truly killing us. I have never felt closer to death in 2021 when I was simultaneously working on these perfumes and beauty, relaunching, designing all this stuff and writing a book. I have never felt more worn thin and I’ve never felt more aware that this is what I need to survive, to be relevant, to have my work out there, to put my best foot forward.

All these markers of respectability and markers of productivity and all these markers that are killing us, I’m very aware of that. I’m very clear about my boundaries because I feel like this world wants to take those away from us. And this world doesn’t understand boundaries, it only understands borders. I feel like the process of writing this book is to transcend this idea of dominance and borders and to just be like, “Look, these are truths that I have imagined and things that I have inherited. And they have value and they should be read and they should be understood and they should be held with respect.” Which is something that the industry has a really hard time giving plenty of writers.

I know people who have made $350,000 for their books. That’s not my experience. One day I’ll write about it. Do I think my book is not worth $350,000? I think it is worth that, I think it’s worth more than that. Does that mean that the publishing industry sees my Bangladeshi Muslim femme book as worth that? What is Bangladeshi femme life worth in this world? How many stories do we have to read about the ills of the garment industry, which I write about? How many stories do we have to read about laborers in the Arab world being shipped back in shipping containers because they’re dead, before the dominant culture cares?

This is the invisible specter of Bangladeshi femme life and labor that exists. And it’s not just us, it’s Black women’s life and labor, it’s Indian women’s life and labor, femme labor. This specter is omnipresent to the point where we can’t even acknowledge it, we can’t hold it, we can’t honor it. The well of rage…It’s so deep but it gives me clarity.

What is decolonized beauty to you?

I think we all need to return to our innate beauty that connects us to our own power, our own embodiment, and our own connection to the earth. The earth is innately beautiful and our presence on the earth is disruptive to that process and that flow. That is part of the human experience, disruption. And that is also why beauty is really dangerous when it becomes supremacist or part of a beauty hegemony or exclusionary. Because that makes certain bodies and peoples ugly and unbeautiful. The way that I felt as a young person in my embodiment, there were times when I would feel as though I were the ugliest person in the room that I was in. Which absolutely anytime I’ve heard a person say that, I can see the part of them that is actually beautiful. Not in a way that feels like comforting them or false, it’s very real, it’s an energy from within.

Knowing your power, knowing the space you take up, knowing the way that you move, knowing the way that you feel is innately something to cherish, to adorn if you wish, to be unadorned if you don’t. To decolonize beauty for people of color, to use the phrases of this present day that we’re in even though what I’m talking about is beyond that. I think for many of us it’s really to love the life coursing through our body. Whether it’s the way things fold, our skin folds, our skin sags, our skin shines, the twinkle in our eye, the softness of our touch… those things are beautiful.

But I do know that I am a brown-skinned person who came out of a light-skinned person’s body. And that person, my mom, always made sure to let me know “you are beautiful and no one can ever tell you otherwise.” I think every person deserves to receive that love. And that is really hard for people to give to people who do not fit into hegemonic ideals and standards of beauty. But beauty has no standard, beauty is an innate force that is governing the way everything in the cosmos is messily chaotically, but also rhythmically aligned. It just is. To gaze at the ocean is to know beauty, to see the sunset every day on the river, I know beauty. To be rained on is to know beauty. These are just things that we are not in touch with.

Yes, it is gold, it is a red lipstick, it is gold jewelry, it is the bling that I love, it is that. But that’s only a part of it. What does it mean to put on my face paint, my warrior paint, whatever you want to call it? That whole ritual is connecting me to something divine.

The other part of the conversation is how beauty is destructive, beauty is a privilege, beauty is constant politics of desire. That is a very limited way of understanding beauty and people do need to connect beyond that external. Clean beauty and yoga and veganism, it feels toxic because it feels like judgment. It feels like cultural superiority and racial superiority.

I feel that idea of wellness belonging to people who are already super privileged just ugly and actually not addressing the people who are harvesting the turmeric that you’re putting in your latte, the cultural practices that you’re taking from that erased the Dalit and East Bengal cultural lineage from that practice of tantra or yoga. To me that is deepening the conversation of beauty. It doesn’t have to be the surface, but we feel most safe and comfortable at the surface.

I’ll be walking in the street wearing something slutty. I love to dress slutty. And yeah, it’s because I grew up in a Muslim household. Then there’ll be a woman on the street who’s just femme, fabulous, dressed just as slutty as me. And we will just look at each other and be like, “You look great, you look hot.” And we’re just doing it for each other. To me, those are the moments where I’m like, “I live for that.” We can’t even make eye contact with people, we can’t even acknowledge people when they’re giving us that. So decolonizing beauty, it just needs to return us to our innate, inviolable beauty that reminds us of our connection to the earth and each other. That is the core of it for me.

TANAÏS Recommends:

Divination: I use the I-Ching daily, this ancient Chinese Book of Changes has been banned throughout history, a reminder that our pursuit of the sacred comes has a grave consequences when we are confronted by those who wish to destroy this part of us for their own power.

Meditations on impermanence: center your gaze on the blue flame of a taper candle as it melts down into a puddle.

Decolonizing our beauty by letting the hairs grow, letting our skin be its true self: mottled, freckled, curvaceous, pigmented, hairy

Decolonizing our art, reminding ourselves constantly that we do not have to live as an informant or translator of experience to the dominant culture, being seen by others is not the same as speaking your truth, and the desire to be seen can often occlude the spirit of our art. To touch the unknown through language, strokes, notes, never seeking perfection or acceptance, but that moment where you remember: I am enough. This is enough.

Ujjayi orgasms have recently brought me a lot of pleasure. Breathe a deep yogic ocean breath through the nostrils, release through the nostrils while making a sound in your throat akin to ocean waves, a churning that will eventually course through your body. Release.

- Name

- TANAÏS

- Vocation

- writer and perfumer

Some Things

Pagination