On balancing personal and professional work

Prelude

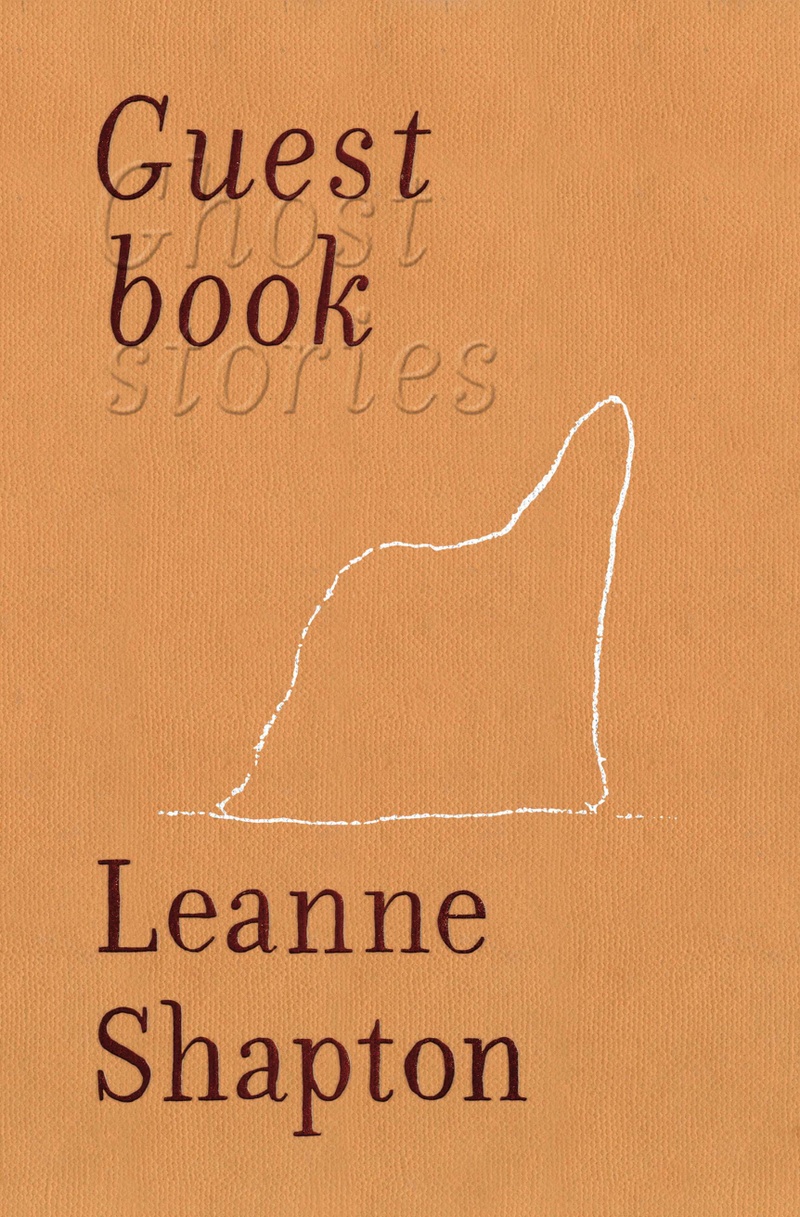

Leanne Shapton is an artist and writer, and the co-founder of art and photography imprint J&L books. Her published works include Was She Pretty? (Drawn and Quarterly, 2006), Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry (Sarah Crichton Books, 2009), and Guestbook: Ghost Stories (Riverhead, 2019). In her youth, Shapton was a competitive swimmer who competed in the 1988 and 1992 Canadian Olympic trials, an experience she describes in her autobiographical book Swimming Studies (Blue Rider Press, 2016). She also creates illustrations for book covers and feature films.

Conversation

On balancing personal and professional work

Writer and artist Leanne Shapton on developing her own style of storytelling, chasing down your most resonant ideas, and working whenever you can, however you can.

As told to Maura M. Lynch, 2705 words.

Tags: Art, Writing, Process, Production, Inspiration, Beginnings.

How do you like to define what you do?

I write with words and pictures. I think that’s what I do. I like to make up stories and worlds where you read images as importantly as you read words.

Do you have a creative routine or consistent practice?

No, and it’s gotten even more inconsistent. My daughter is five. In the last five years I’ve always had a desk to work at, I usually have a studio, but I feel like I wrote Guestbook in notes on my phone. You know, in the passenger seat of a car, or waiting to board a plane.

I think that whole idea of, “I need my cup of coffee and quiet,” just doesn’t work for me at all. I think it would be lovely if I had that. All of my writing happens—and all of my practice happens—when I shove it in. I’m a working illustrator and a working journalist; going back to something like [working on a book] where I’m not being paid hourly or a word rate for it, it really just gets done when it can.

I taught for the first time last semester. This is something I try to tell the students [in Columbia’s graduate creative writing department]: However it happens, it happens. You just have to really work hard. Nobody says you have to have a set routine.

Funnily enough, I had so much of that [routine] when I was a swimmer. There are certain practices when you actually do have to be in one place, like in a pool, to get stuff done. I think I try to discredit this; it’s that dumb focus that you need to get it done, but where that dumb focus happens and how, I just sort of carve out wherever I can. If it happens on a drive, or at night ‘cause I can’t sleep, then that’s when it happens, you know?

How do you know when you’re onto something, like you have a good idea? What does that feel like, or what is the feeling that you’re chasing?

The first thing that comes to mind is saying if I think it’s good enough.

Is that something that you can articulate?

It’s a gut feeling. I guess it’s as though something is reaching a standard and sounds true.

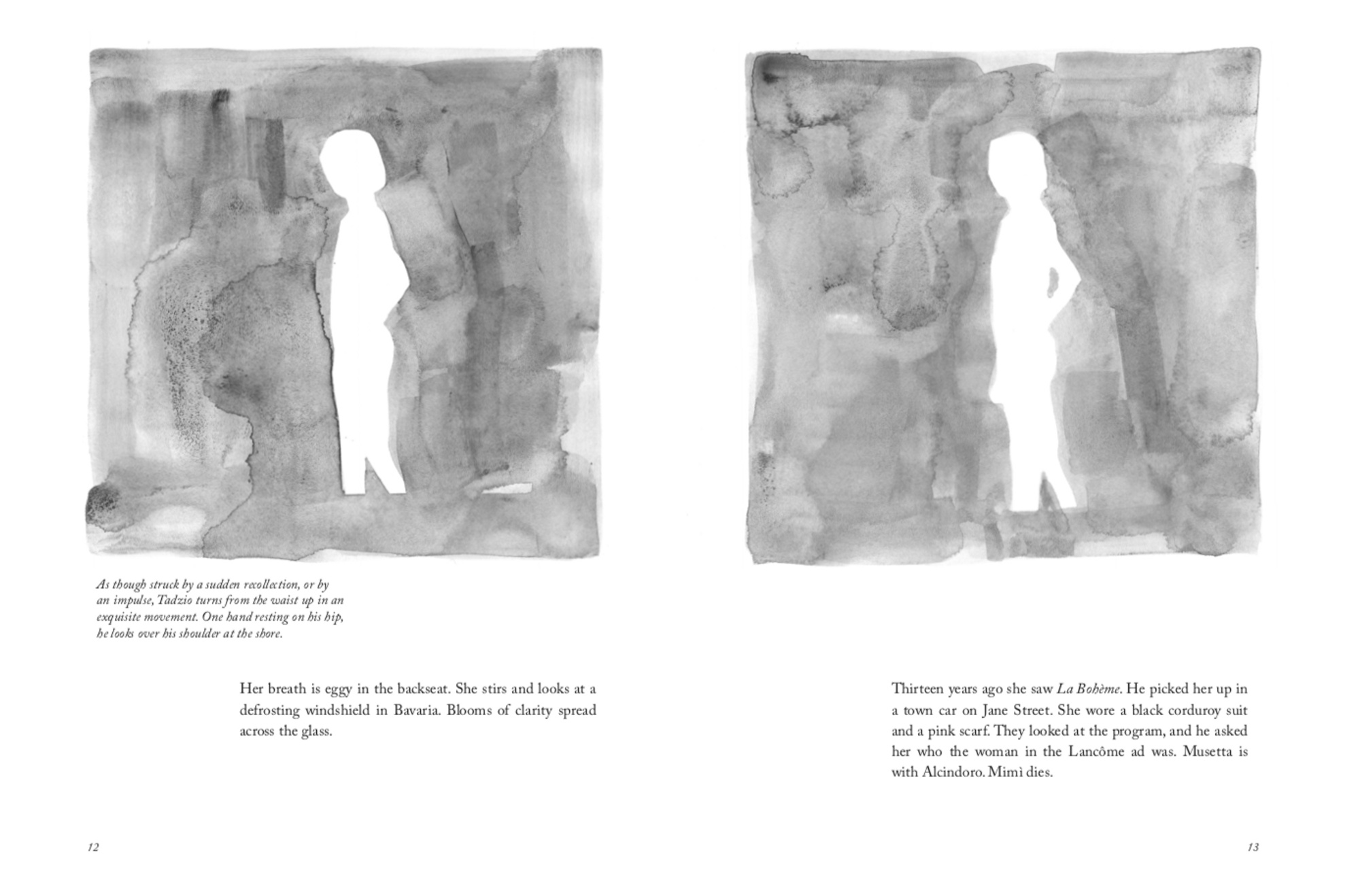

“Eidolon” for instance, one of the first stories in Guestbook, takes the final scene in Death in Venice, where Tadzio wanders out into the water, and there’s this beautiful little motion of turning back and looking. For the longest time in drafts I just had pictures I’d taken off of the computer monitor of that scene [from the film]. I had the writing, and it sort of felt like it was coming together, and then I thought, “You know what? I don’t want to deal with copyright, I’m gonna paint those images.”

It was just an exercise; I didn’t know which way to go. In painting them it just started to feel right, the distance between a photograph and a painted image of a photograph said something about memory that felt right to me.

Excerpted from “Eidolon” in Guestbook: Ghost Stories by Leanne Shapton. Copyright 2019 by Leanne Shapton. Published by arrangement with Riverhead Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

I’ll just experiment, and that will help it feel good enough, or true, or right. There’re garbage bags full of this where it didn’t work, too. But in that instance, one of the practical issues was I didn’t want the headache of trying to get copyright for pictures I’ve taken off of my monitor. When it all came together, I thought, “Okay, this feels right.” I don’t know if anyone else will think that, but that’s what it winds up being.

It sounds like you do a lot of things, and it just starts to become obvious which ones are more resonant than others. Like, the experimentation allows you to internally edit the ideas and sift through them.

I love double-channel, triple-channel writing—where you’ve got an image, you’ve got a caption to the image that’s very literal, and then you’ve got another set of writing that’s another layer. Honestly, I got that from the Bloomberg monitor on television, just how you can see all this information sort of gliding by in taxicabs. You’re basically watching three or four modes of communication [at once].

If one of them’s working, then that allows me to focus on the other ones. So once I got the images and the captions, which are literally quoted from the screenplay from Death in Venice, then that made me go, “Two down, one to go.” But now, how do I [write] this story of revisiting an author, or revisiting a scene, revisiting a photograph, revisiting a love?

This is a long-winded answer to your question, but once one of the channels is working, than that frees up me to go, “Okay, let’s nail the third channel,” and that’s usually the hardest one. Writing is a lot harder than painting. Like way harder.

Why do you think?

I’m not as practiced at it. I’ve always read, and I’ve always written, but Swimming Studies was the first [writing] I’d ever really published. It was a huge experiment. And it doesn’t flow, you know?

And I think it’s just ‘cause I’ve been doing it far less. I’ve always been in art departments, and not on the edit side. It’s only in the last 10 years that I’ve really focused on my writing, even though I’ve been reading, and taking in my standards, and what I think is good, for years and years.

I feel like I got my education in that at Harper’s magazine in the late ’90s. I was like, “Now I understand the nuance of good journalism.” That started me paying way more attention to how to write than how to illustrate and draw and paint and art direct.

It kind of reminds me of learning a language. Like, the first language that you learn you are obviously fluent in. And then the second one, there’s more of a learning curve. But I also think that can lead to really interesting output.

I was asked recently sort of like what writers I admire, and I had been talking to a couple friends before about Miranda July’s first novel, The First Bad Man. It was so good because, again, she didn’t come out of a creative writing program. She’s got standards she’s found, because she’s got a good ear. I have this theory that if you’re—and I’m not saying this applies to me—but often if someone’s really good at something, they’re also really good at something else. Like when musicians write, or when writers play music, or when filmmakers write. I love when people go out of their discipline, because their standards follow.

Sometimes they don’t. It doesn’t always follow through, but I wanted to try, you know? I really wanted to try, because I love reading so much. I wanted to try to write.

What inspired you to first want to share your work with other people?

I think my interest in design. Design is shared. Design relies on an audience. I had this interest in Push Pin Studios, from New York, this interest in communication design and graphic design. I looked up to both fine artists and illustrators, quite equally. At a certain point more so the design, because I just saw how alive it was, how low and high it could be at the same time.

I just tried to get illustration work with a newspaper in Canada, with The New York Times Book Review… It was almost like “publish or perish,” but it was my drawings I wanted published. That’s typical for an illustrator, you bring the portfolio around, the way that writers submit stories to places. You just want to be published. It was a case of, “Could I communicate?” And not in necessarily a fine art way, but in a communication design way, in an editorial way. So my first job came from Globe and Mail in Canada, and The New York Times. That general interest audience is really still really important to me.

I actually didn’t do really well as an illustrator, at all, until I found the marriage of metaphor and word and image. I was like, “Why am I not getting any work?” I really had to find my place in where that was.

How did you kind of find that niche for yourself? Was there one work where you were like, “Oh, this is it”?

The first thing that comes to mind is probably Native Trees of Canada. That was a very personal project, a gift to my ex-husband. I found an old park ranger catalog from 1979 that was all these leaves shot in black and white, and I just wanted to paint them. Simple. Just, “Oh, I want to paint these. And I’m gonna tell my British husband about Canada.” I did 40 paintings, and they were in this bound sketchbook. Then Chris Oliveros, the publisher of Drawn and Quarterly at the time, was in New York, and we were talking about doing another book, and then he saw that book and said, “Oh no, this— this I want to publish.”

That was in 2010. I had just stopped working as an art director at the Times’ op-ed page. In terms of illustration, that was a big point. People would started taking those paintings, and [saying] “Can you do something more like this?” or “Can we use one of these for a book cover in Norway?”

The work came out of that that was far more suited to what I felt and cared about. I really have to give Chris Oliveros a lot of credit. There are these people that kind of almost give you a nod somehow. And those people that are always really good editors, really good readers, really good publishers. I just feel super lucky.

I wanted to talk about Was She Pretty?, a book about relationships. You were saying Native Trees was so personal, and I know Was She Pretty? was fiction, but it also feels very personal. You’re exposing these qualities, like envy, that people often try to hide.

Oh yeah, I’m obsessed with jealousy.

Was exploring that something that seemed really obvious to you? Or were you like, “This is driving me crazy. I need to just figure out what my relationship is with this”?

It was both.I really want to find out why I’m obsessed with things.That book has so many of my own stories in there, and I was trying to articulate what drove me crazy. When I was working on that, I would talk to people about their jealousy, which was fascinating. People’s behavior is so bananas—and so real—it’s incredible. It’s emotion, and it’s fear. I’m interested in fear.

Jealousy can be kind of motivating, too. Has that ever factored into your work?

In terms of competition with my work, not really. I’m kind of lucky in that with every project I try to go, “What hasn’t been done before?” not, “Can I top something else?” It’s almost a competition of invention that I’m interested in. Can I do 10 channels in a story next? I really don’t feel much competition; it sounds so weird, but I almost can’t even compare myself to the writers I love, because I’m not doing anything close to how wonderful their work is.

I just really think a lot of my work slips between the cracks. I get a little pay here and there, but I feel lucky that it doesn’t have to stand up against something else, you know? I risk obscurity, I risk being completely ignored, but it gives me some freedom to not have scrutiny.

Like a lot of artists, you don’t have that thing, like in a traditional workplace, where you’re up for a promotion or you have structured goals to meet. How you kind of challenge yourself to grow in your individual practice?

Guestbook really helped with that, because it was going back to that idea of invention. I really have to think and trust a reader, and that reader is the competition. If I put this work in front of my mom, or my aunt, or my brother, or I put it in front of a peer like Sheila Heti or Jason Fulford, how far can I go? What will work based on how scientifically, evolutionarily, how people read these days? Will my mom get as much from it as Jason will? Will it still work? It feels very laboratory-like. And that feels like what I’m up against.

I’m always going, “At what point do I lose the reader completely?” or “At what point do I gain a different reader because of what I’m doing?” In the last four years when I was putting together Guestbook, that balance was what I was up against. It almost feels like baking. Like, at what point will the middle collapse? Will it hold?

I wanted to ask you about the professional side of your work, the projects that you get paid for by other people. What’s your approach for those projects versus your personal work? Does it feel similar? Does it feel different?

It feels desperate! [Laughs] I wish I were more professional. I say yes to most things, because I need the money. I mean, we live in New York City. I honestly say yes to pretty much everything, whether it’s a job for 200 bucks, or a job for $20,000. It’s a little bit scattershot, based on what I’m working on, or what I’ve got due, but I am constantly on deadline, because I need to make money.

As a result, the professional work really does get as much attention as the personal work, because I want to care about it as much. I don’t really have a like, “Well, that’s a money job,” because I don’t get offered enough jobs to… I’m in a bit of a funny head space with that; I just don’t make a lot of money.

This is another thing that I tell the students, too: If you do what you love, more times than not, it’s gonna be be a bit of a struggle. I’m not in debt, I’ve always been able to pay my bills. But it’s a constant struggle to balance the work that I get paid for with the work that I don’t.

I feel like if I’m not doing the work I don’t get paid for, the other work will suffer. Like I have to do it to push it along, to get new ideas. You can’t just recycle idea after idea for book covers—you have to be constantly reading, constantly looking at stuff. So if I’m not doing personal work, that underground stream doesn’t get fed.

There’s always non-paying work that I have to do, and then that will influence the professional work. And sometimes I can reuse it. Like there’s this book cover and I go, “Oh, I just painted this tulip.” And then it cross-pollinates, which again, I think is the ideal. It helps me keep doing the personal stuff.

I appreciate you being really honest about that. It’s hard, you just see people making work, and you’re like, “How do they make it work?”

Yeah, you don’t! [Laughs] Like, I don’t know how to pay my rent on a very regular basis.

Leanne Shapton recommends:

- Women Talking by Miriam Toews

- Cocktails at Nix restaurant

- Stonehenge Aqua hotpress watercolor paper

- Lake Superior in the summer

- Name

- Leanne Shapton

- Vocation

- Writer, Artist, Illustrator

Some Things

Pagination