On performance, chasing perfection, and resisting the need to explain your work

Prelude

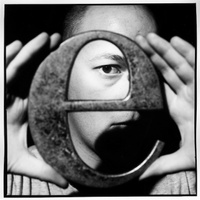

Eugene Robinson is an author, journalist, and vocalist who has fronted the avant-garde rock band Oxbow since its inception in 1988. He is the author of Fight: Everything You Ever Wanted To Know About Ass-Kicking But Were Afraid You’d Get Your Ass Kicked For Asking, and the crime novel, A Long Slow Screw. He is formerly the vocalist of ‘80s punk band Whipping Boy and has participated in way too many musical side projects to list here. He is currently an editor at OZY.com.

Editor’s note: The TCI team would love your feedback on what you found helpful in this interview. Scroll to the bottom if you have a moment to respond to a few questions.

Conversation

On performance, chasing perfection, and resisting the need to explain your work

Author, journalist, and rock vocalist Eugene Robinson on striving to be your most fully realized self, the complicated juggle of maintaining a work/life/creativity balance, and letting your work speak for itself.

As told to J. Bennett, 3809 words.

Tags: Music, Writing, Focus, Time management, Inspiration, Process, Multi-tasking.

You do many things—write lyrics, novels, non-fiction and perform onstage. Do you have an overall artistic philosophy?

That’s a complex question, but what you’re saying is, “What is a through line that we could draw from the first striving and struggling efforts, to the last thing you just wrote?”

The through line for me is that there’s this weird book that I once read called The Bezels Of Wisdom. You’re going to have to excuse the cheesy title, but it’s by this guy Ibn Arabi, and he talks about this concept of looking in a dirty mirror and then he marks his progress through life. It’s very much an analog for cleaning this mirror, so that eventually you get more of the dirt off and then the reflection is completely accurate. You’ve shined it as much as you ever could possibly shine it and it ceases functioning for you like a mirror.

You don’t have a sense of it being a mirror anymore, and if you listen to the Oxbow records one after another, it’s pretty clear to me that, in a very gross motor skill sense, we are trying to make a bad record [laughs] but in fact what’s happening is that we are making the most perfect Oxbow record ever—and we’re getting closer to that. It’s kind of like trying to hit a note that nobody else hears and you try and you try and each record represents a step toward a perfectly shiny reflection—so shiny that you don’t have a sense of it being a mirror anymore.

It’s like that with the writing, too. You could probably look through the odds and sods and then go into A Long Slow Screw about getting almost murdered by this mob enforcer guy when I was, like, 17. Every word or turn of phrase, the rhythmic portents of the story, would be familiar to anybody who had read A Long Slow Screw, but I’m clearly trying to get to a most perfect understanding, for me, as the artist and creator, as humanly possible.

The stuff that I do that I don’t like, I would have to put in that category, like the last Whipping Boy seven-inch, Crow. That is a representation of a mirror that’s as dirty as you can get. There was nothing to see there. [laughs] No attempt to create a medium by which I could see or by which others could see. If I was honest, it was really just a misbegotten piece-of-shit project. That’s probably my lowest public artistic point. But otherwise it’s been a pretty steadfast and effortless journey toward a more perfect understanding of self.

How’s that for a perfectly crunchy California way to describe the artistic vision? [laughs] It’s easy to say that life is darker, full of cul-de-sacs, some shit like that. That’s not really what I’m thinking about when I’m creating.

This perfection you’re talking about—whether it’s with Oxbow, music in general, or writing—do you think it’s actually…

I don’t really view that as a state. I view that as a gerund—not a noun. It marks more clearly for me a way of doing something. The degree to which I know I’m succeeding is if it infuses everything else I do. I think it’s fairly certain to say I’m always suspicious of artists who seem to mark growth with their work but have no personal growth, and vice versa. It just seems to be a really weird discontinuity, and I would hope that there’s a one-to-one correlation between who I am and what it is I’m making—always. This has been a topic of discussion a lot lately because of the whole artist versus the art thing.

Do we like Dave Chappelle? Do we not like Dave Chappelle? Do we like H.L. Mencken or do we not like H.L. Mencken? What do we forgive? What do we remember? What do we forget? I’ve always been very uncomfortably direct and there’s never been any guile. I’d like to imagine the same thing is happening with the art that I make, the literature, the music. That’s my hope. I’m kind of mired in this burning teenage desire for authenticity, but since it’s always been a part of my personality, I don’t really feel like it’s that adolescent. I hated phonies when I was two years old.

This perfection, then—it’s not necessarily something that you feel you can actually achieve, but it’s important to chase after it?

Yeah, in every regard. It wasn’t really his theory—because he was a Nazi, and Nazis steal—but I think Albert Speer kind of embraced it and popularized the theory of ruin, that buildings in their decline should look as good as they did when they were first built. At any given point were you to check on me, I would hope that I’m being some best version of myself, even if I’m doing something that is completely retrograde. [laughs] Again, it’s not a state; it’s a way of being. I could colloquially break it down, too: I’m just trying not to be full of shit, and it’s a full-time job.

I want to go back to what you said about the Whipping Boy seven-inch being your low point artistically. What did you take away from that experience?

Well, I knew what was going on with it right away. One, I think we did cover songs—and we played well. I sang well. I still love the original songs. I think it was more about trying to engage a player who was not feeling artistically fulfilled. I’ve since learned that when you start hearing crap like that from somebody in the band, or somebody that you’re making a project with, it’s like when somebody that you’re in a relationship with starts talking about sleeping with other people. “Oh, okay, you should go do that right now, like immediately. Let’s not waste any time because clearly you’re not being fulfilled here.”

Instead, what I tried to do was let him drive it. He came up with the artwork and he came up with the title and it’s just a really misbegotten thing. The production of significant works of art typically are not going to come out of committee, I don’t think… Well, maybe that’s the wrong way to say it. You can do it with a committee but it’s going to be a committee of individuals around a common goal.

Right. Everyone is on the same page.

There’s a reason why the personnel of Oxbow never changes. We have symphony people come in and string quartets and brass sections and oboe players and pianists, but the core has stayed very much the same because we are similarly involved and try to get our hands around exactly what Oxbow is. And that low point was saying, “Okay, I know what Whipping Boy is, but I’ve gotta engage this guy. I’ve gotta let him feel like he has some ownership, let him buy in, so I’ll let him do it.” That’s not how you make anything that’s worth a good goddamn. It was instructive for me. It’s something that I never, ever wanted to do again, and I never have.

An important distinction that needs to be made about you is that you’re not just a vocalist in Oxbow. You’re a performer. And not all vocalists are necessarily performers in the sense of… I don’t know if “theatrical” is the right word for what you do, but it seems close. Why is that important to you?

I have to go back to people that really impressed me when I first started getting into music. I was into theater way before I was into music, but when you’re a kid and you’re exposed to theater, you’re usually seeing professionals or you’re seeing a school play—in which case I was in the school play, so it didn’t have the same sort of impact on me. But when I first started venturing out to see music, my parents always took me.

My ex-stepfather was a journalist, and we’d go to see Eddie Palmieri or Tito Puente, so I understood live music, but when I went to see live music that I was seeking out on my own it was pretty immersive and overwhelming. I’m thinking of two people specifically. I’m thinking of Klaus Nomi and I’m thinking of the Plasmatics, which seem to be sort of polar opposites but it was like jumping into a body of water, right? There was no room to distinguish or differentiate what was happening, like how your leg felt versus how your shoulder felt. You’re bathed in them, and there’s plenty of types of music where you do not get that. When I started seeing more live bands that seemed to be accessible, that seemed to be responsible for generating this idea in my head, “I could do that and better.” I started to see stuff that I didn’t like. I didn’t like shtick.

Why not?

There are great performers out there who rely on shtick. I’ll give you an example of a guy who is a great performer who relies on a sort of shtick, but it doesn’t diminish his greatness at all, and that would be Marcel Marceau. [laughs] He’s a fucking mime, right, with shtick. It really works. He could really emote and he could really immerse you in the experience. But in general the people who are doing shtick want us to be impressed by the cleverness of their presentation—and that’s fine, but I need for something to happen to me before something can happen to you.

I’m convinced that it isn’t just religious ceremonies—that we can attain a certain type of oneness if we’re all dialed into the right channel at the right time. At certain Oxbow shows we’ve actually gotten to that really kind of cool transcendent spot where, non-verbally, I can look out in the audience and it’s like I’m looking into that mirror that is shining so clearly that I don’t even know it’s a mirror anymore, and they’re feeling what I’m feeling, or I’m feeling what they’re feeling. In any case, it’s a good moment.

But I sing all the time. I sing in the car. I sing in the shower. I sing in the kitchen. My kid was over at my house the other day. She came up the driveway and heard me singing in the kitchen. She was like, “Who was just singing?” And I go, “Oh, I do it all the time.” But I wasn’t performing. I wasn’t trying to communicate a deeper emotional state to a listener. It was just me making noises with my mouth. A lot of people do that and get paid really well for it and god love them. That’s cool if they can do that, but I can’t.

Part of your performance involves slowly disrobing onstage. What inspired that?

It was partly functional. In the old hardcore days on tour, it’s not like I had a suitcase. I don’t think I even owned a suitcase. I had a bag with stuff, and after the show it got wet. There’s a video of when Whipping Boy played with Minor Threat in Lansing, Michigan in 1981 or something. I was actually wearing pants then, but after that show those pants were soaked. They were denim, and they hung in the van and they stunk. Then we had to stop at the laundromat—which is fine if you have money for a laundromat—but if you have to choose between clean pants and gasoline, well, without the gasoline you don’t get to the next show.

At one point I was like, “I don’t want my pants to be fucking wet and now they’re wet and they’re sticking to me.” I think I was in London with Oxbow and I remember saying, “Goddamn it, fuck this. I’m taking the pants off.” I remember looking out in the audience and there was almost like a change in the air, a taste in your mouth, and I’m like, “What is it that animal feeling that I’m feeling right now, that anticipation? And then I go, ‘Oh yeah, my cock is out.’” [laughs]

On the one hand it was very functional, like, “How do I get through this tour with clean clothes and not completely stinking wet?” On the other hand, I realized that there was some sort of an emotional value to it, as well as maybe an answer to what it was that I was really trying to do because I’m not trying to hide from you at all. Writers have come up to me before and said, “I just saw you onstage and now half an hour later backstage you seem like a pretty normal guy.” So I go, “No, no, no—onstage was real. Right now, me talking to you, that’s not real.” Because I’m trying to appeal to you in a certain way. We’re trying to discuss something and I’m choosing words and trying to frame an idea. That stage thing was real. This is the fake.

Over time, that became one of the things that Oxbow was known for—that you were going to slowly take your clothes off during the show…

That’s for the cheap seats. In other words, if you come to the show, there’s some shit going on there that, musically, is not just rock n’ roll. But whatever—if I didn’t like it I would keep on wearing a suit. You know, I wear a suit everyday for work. I’ll typically go from the job to an Oxbow show and I’ll just be wearing what I was wearing at work.

Let’s talk about that for a minute: You go to work everyday as a journalist. In the meantime, you’re writing books, playing in Oxbow, and doing all these other musical projects on the side. And you’ve got a family. What’s your secret to balancing a full-time job and family with your creative output? Are you not sleeping, or what?

I am not sleeping. [laughs] It started when my first kid was born. I didn’t want to rob her of… Okay, my father was a professor and, even when he was sitting there talking to you, he was thinking about other stuff. You could see it. You could feel it. It was a drag. So I just stopped talking to him because it wasn’t cool.

I didn’t want to do that. I wanted to be present. My wife at the time, the mother of my child—I wanted to be present for her as well. I had to go to work every day, but then we have dinner, we have bath time, story time and then I’m hanging out with the wife for an hour or so because she goes to bed at nine or ten. Then I’m going to go to the gym, workout for an hour and a half, come home, take a shower and write until two in the morning. Then get up at six and start again.

That happened for a long time. Then, of course, my now ex-wife complained. She said, “You should get more sleep. You’re a nicer guy when you sleep.” Having kids changes how you sleep. I’ve not slept like I used to sleep before I had kids after I had kids ever again. I don’t know how to describe it, but it really changes how you sleep in a certain way. So I figured as long as I’m not going to be sleeping, fuck it—I can write. That’s how I finished A Long Slow Screw. That’s how I finished the fight book.

With Whipping Boy and then with Oxbow, you’ve traditionally performed in front of mostly white audiences. Is that something you even think about anymore, or does that not enter your consciousness at this point because you’ve been doing it for over 30 years?

You know what else I did today? I drove on a mostly white freeway. When I parked in the parking lot I saw mostly white people in the parking lot. In the building I’m presently sitting in, I see mostly white people. There’s an Asian guy sitting about ten feet from me. But right on the other side of me is a white person. I don’t know if you noticed, but white people are everywhere, like dead people in that movie The Sixth Sense.

[laughs] Fair enough. But the white people I’m talking about are specifically there to see you and your band.

Well, you have to understand I’ve been on the stage since I was two. I won some kind of modeling contest when I was two, so people have been taking photos and looking at me for a long time, and I’ve never… I think America is comfortably obsessed with race in a way that I’ve never been comfortably obsessed with it. I’m not uncomfortable with it, but it’s not like I went to see Klaus Nomi at the fucking Mudd Club in 1979 and looked around and said, “Hey, I’m the only black guy here.” When I was working out in the gym in John Gotti’s neighborhood I wasn’t like, “Hey, I’m the only black guy here.” God love Americans and their obsession with race, but I don’t give a shit.

You know what’s confusing and baffling and slightly amusing to me, though? On the rare occasions when other people like me have stood up, like the Black Rock Coalition, or Afropunk Festival, I’ve reached out to them. And they’ve given me nothing but the high hat. We’re not talking a long time ago. I think I wrote the fucking Afropunk people a couple years ago saying, “Hey, I would love to play one of your shows.” Then they did some documentary on blacks in punk rock and they interviewed everybody and didn’t talk to me and then somebody was like, “Why the fuck wouldn’t you talk to Eugene?” So the guy called me. He goes, “Look, the film’s already edited and we’re not going to go back, but we can talk to you for the book or for the article.” So they interviewed me for the book.

But it was never weird to be looking out at an audience of white faces. On occasion it’s been weird to me to look out and see an audience of angry people. [laughs] That’s happened. That’s usually because the night has taken a left turn or a right turn away from our intended target.

My last question has to do with a story you told me many years ago. We were talking about resisting the tendency to explain one’s work, and you told me a story about a classical pianist in the 19th century who was premiering his newest piece in front of a live audience…

Yep. I think it came from Beethoven, although if [Oxbow guitarist] Niko [Wenner] were here, he would probably correct me. So back then, there were no record labels—these guys had patrons. They lived off the money of rich people. And at the end of this piece, some rich woman comes up to him and says, “That was wonderful, but tell me, what did it mean?” And he just kind of looks at her, sits down at the piano, and plays it again.

I’m communicating to you in the best way I know how, you know? If I could pattern a more effective way to do it, I would have. It’s not like I’m choosing an obscure way to be obscure. I’m choosing the way that I think I can most effectively communicate this mélange of thoughts, feelings, impressions, and dreams. I think that’s what appealed to me about that story. It’s interesting when somebody is asking what something means. I’m thinking partially it’s curiosity, but a lot of times it’s a weird kind of hostility… like, “Do you know what you just did?” “Can you explain it to me?” Or rather, “How do you explain to me what you just did?”

It’s accusatory.

Right. I don’t mind talking about what it means, but it’s not going to be a complete conversation because I only write the lyrics and do the vocals. Even if I tell you what the words mean I haven’t explained the song to you. I haven’t done anything except talk. That’s why I like the story about just sitting down and playing it again. Then people go, “Why can’t you explain it?” People want to get it. But what is there to get?

Look, I have a hard time with calculus. It’s not simple. I might have to ask someone four or five times to explain Quadratic Theory to me. But music? No. I got ears. I can handle it.

Eugene Robinson recommends:

1] The Servant, a film by Joseph Losey: a blacklisted American decamped to the U.K. to make movies. This early ’60s import with Dirk Bogarde and Sarah Miles based on a book by Robin Maugham—related to Somerset—is an evilly slinky movie that I would advise you to see without watching a trailer or reading a single review of it. Nothing but my word. I used to use this to harrow my friends. If you did not watch it or watched it and did not like it? We were done. Yeah: that good. I watch it probably every six months just to remind myself of what genius smells like. And yes, I just watched it.

2] The Elementary Particles, a book by Michael Houellebecq: the last book I read. Reminds me, in total, of that Raymond Pettibon illustration of Manson sitting in his jail cell looking into a mirror that he’s scrawled on with lipstick, “I’m sick of sex.” Anomie around sex seems long overdue to me now that they use it to sell everything to everyone or nothing to no one. And still? This kind of febrile panic about it, too. Really nice.

3] The painter Cleon Peterson. A friend of mine was friends with him early on and told me to buy some of his stuff since I ranted and raved about it. I really liked it. And I did not. And now I can’t. Way too rich for my blood. But he paints the way I think, it seems to me. And there’s a stolidity to his work that often depicts violence, but without the hysteria usually reserved for depictions of violence. Me like.

Honorable Mention: tattoos by Sade (she does them now, apparently), Interpol, Death Grips, Kim Gordon, Daughters, and the Italian translation of my novel A Long Slow Screw… due in six months!

- Name

- Eugene Robinson

- Vocation

- Writer, journalist, vocalist

Some Things

Pagination