On a lifetime of literature

Prelude

Stephen Dixon (1936-2019) grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with six siblings. Before he became a college professor at the age of 43, he worked as a school bus driver, a bartender, a systems analyst, an artist’s model, a middle school teacher, a department store clerk, and a reporter in Washington, D.C., where he interviewed John F. Kennedy, Richard Nixon, Nikita Khrushchev, and L.B.J., among others. He taught at Johns Hopkins University for 27 years. He is the author of 18 novels and 17 short story collections and published over 600 stories in his lifetime. He was a recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and two National Endowment of the Arts grants. He was also a two-time National Book Award nominee—for his novels Frog and Interstate—and his work was selected for four O. Henry Prizes, two Best American selections, three Pushcart Prizes, one Best Stories of the South, two stories in the Norton Anthology of American Literature, and possibly others he was too modest to list. He passed away on November 6th, 2019, at the age of 83.

Conversation

On a lifetime of literature

In his final interview, the late Stephen Dixon discusses his own lifelong writing practice, what it means to loosely fictionalize your life in your work, making peace with rejection, and the value of always working on something new.

As told to Joseph Grantham, 5228 words.

Tags: Writing, Process, Inspiration, Beginnings, Success, Failure, Day jobs.

Did you read much as a child?

I did. I read comic books a lot. And my favorite book was Home Run Hennessy. It was a sports book and I liked novels about sports characters. I was also a big Jackie Robinson fan. So I read all about Jackie Robinson. I didn’t read as much as my closest older brother, Jimmy, the one who died in a freighter coming back from Europe.

I read somewhere that it was Jimmy who told you that you have to finish your stories.

Well, one day I had my apartment in DC at 1875 Mintwood Place, and Jimmy came and stayed with me and I said, “You know, I’ve been writing short stories,” and he was a short story writer and a bonafide one—he had been writing short stories for a couple of years. He said, “Well, let me see them.” So I gave him about 10 stories that I had first drafts of… and I heard him sort of making noises. Jimmy had a heart murmur and so I went in thinking something was wrong, and he was laughing at my stories. He said, “You know, these are good, some better than others. But one thing you have to learn how to do is write an ending, finish the stories,” and so I started finishing my stories.

How do you know when you’re done with a story?

Well, the first draft I write in one sitting; 90% of them have been written in one sitting. It usually takes half an hour to an hour, and five pages, 10 pages, 15 pages. So I have the basis and the skeleton for the short story and the trick is, does the story stay with me through the next day when I start refining the story, and start from page one of my first draft and work to the end? This could take a month, could take two months, could take two weeks. But if I feel good after I finish the first draft, I say, “Yep, you got a story here.” And I start rewriting it, writing it from the beginning, with what I have, to the end.

And you start over on the typewriter with your first draft next to you?

That’s right.

Did you ever try working on a computer?

I have more trouble writing on a computer than I have writing on anything. I can’t even work on an electric typewriter. Of course, now with my arthritis and my Parkinson’s, I’m having a little trouble typing. I don’t have the dexterity that I used to have with my fingers. You know, say I have a first draft and I start with page one. In the old days, I would write that page one 20, 30, 40 times until I felt, “Okay, it’s good.” But in the back of my mind, making sure that I wasn’t overwriting, that I wasn’t embellishing to a fault. So I would write that first page 10, 20, 30 times. Until I’d say, “Okay, you can’t help the story anymore. You can only hurt it, or you could do one or the other. But go on to page two.”

Now, because of the limited time I’m able to work on a typewriter, I only rewrite that page once, twice at the most, three times. But I read that page a lot more times than I used to read the page before. In other words, before, I retyped page one and then put it in again, read it and retyped it and retyped it 30 times. That’s not an exaggeration. Now I have the first draft of page one and I start the final draft. This is only in the last couple of years. And I try to make that final draft of page one done in a day. Usually it takes two pages, at the most three. So the mechanics of my writing have changed. I mean, now I couldn’t write 30 pages in three days because of my physical limitations. But I don’t think my writing has suffered from it. I’ve been writing for so long, for 60 years, and just about every day in the last 60 years I’ve worked on my typewriters.

Your writing has evolved. You’re constantly reinventing the way you tell a story.

I am doing stories over. I’ve been concentrating sometimes on a story that I’ve already told, but I tell it in a different way. For instance, “The Breakup,” which was based on a breakup that I had with my wife Anne when she left me at my 29 West 75th Street apartment and she said, “This is not going to work.” So I’ve written that story. Once I call it “The Breakup,” another story is “Another Breakup.” She lived at 425 Riverside Drive, an apartment building in the Columbia University area. And we’d see each other every day. I would go back to my apartment and then come back to hers and one day I came to her floor, seventh floor, got off the elevator and heard her playing the piano, Brahms’ “Intermezzo.” And it was beautiful.

Well, I’ve written that story in different ways about three times. I don’t think anybody’s ever done that. But I do it because I get deeper and deeper into the story and because the emotion of that event, of hearing Anne play the piano and waiting until she stops playing before I ring the bell, or if I had a key to her apartment, before I opened the door, because I don’t want to interrupt her. It seems by rewriting it, I get a different story.

Is it true that you send a story to The New Yorker every year?

I probably sent my last story to The New Yorker a year ago. I started sending stories to them when my Paris Review story was accepted in 1961. So I probably sent to them for about 50 years. They’ve probably rejected 150 stories of mine, so I don’t send to them anymore. In fact, I don’t send out to too many magazines anymore. I have a lot of lasts in my life. You know, I published a lot. I published about 600 stories. The reason I don’t send to The New Yorker anymore is because it’s hopeless. And so I’d be sort of a little crazy to continue to submit to a situation that I know is hopeless. And somebody else might say, “Why do you think it’s hopeless? I mean, how do you know that they won’t suddenly like the newest story?” I’d say, “Because it’s 150 stories later…” And what are they going to say and what am I going to say? “Well, congratulations, Steve. You got a story published in The New Yorker.” And I would say, “Yeah, after 150 stories. So it looks bad for both of us.”

You said that there are a lot of lasts for you lately. How does that feel for you? It also makes me think of the title of your newest story collection–unpublished as of right now–Out of Time.

I’m still writing, but I’m gradually running out of time. I’ll soon be out of time and so there are lots of lasts. This is the last interview and I think this is the last book I’m writing, too. I’m on page 316 and 317 and it could be the last book because it’ll probably go on forever. It’s not a book that has an ending. I changed the title again. Remember [in an email] I said it was going to be Half Stories/Full Novel? I changed it to Stories Without End. I don’t like that anymore because it’s too much like The Man Without Qualities. So I think Half Stories/Full Novel is what it is. Meaning that none of the stories have to end, but altogether they’ll present a life. I’ve done endings enough. And my endings have always been easy for me to do because I don’t like fake endings, endings where you know that’s the end of the story. So I have all these half stories, three-quarters stories; but they have no endings. And it’s fun and it takes a little pressure off me. I just have to write a story or part of a story where a man’s life materializes on the page but doesn’t necessarily complete itself. The story doesn’t complete itself. It can be anything.

So yeah, I think this is my last book and if I suddenly get a heart attack and can’t write anymore or die, the instructions for the book would be go back to the last completed half story. Each half story starts off with a title. The one I’m working on now is called “The Loser.” And it starts off with the words “he’s lost his wife, he loses his wife again, he loses her at a party.” So go back to the end of the last complete half story and that’s where the book ends. The book has no windup, no significant ending, but you come out knowing the guy who holds the book together, which makes it a novel. He’s in every story.

And last, what else? That’s it. Last submissions to certain magazines. I mean, why send to magazines that send me back anonymous rejection slips. I can tell by what they’re saying that they’re not interested in my work anymore. So why bother them and why bother going through the process of submitting a story when you almost know it’s not going to be accepted? I can tell by what they say. Agni Review are still enthusiastic. Idaho Review has been wonderful. And I think those are the only two magazines that are still interested. So I’ve run out of magazines.

Does that bother you?

Oh, it’s fine, it’s fine. I’m old enough to accept that. And I think it’s sort of humorous, too, having written for 60 years, with 600 or so published stories, and then to still face the rejection squad. I mean it used to be where I would–20, 30 years ago–I would send out 20 submissions before I would get one acceptance. And then it became 10, then five, and now it looks like it’s back to 20. I mean, that couldn’t bother me. I just say, “Well you know, they don’t want it.” And so I’m sending out fewer stories. I recently sent one to Harper’s because there’s always a chance with them.

And these are all sent physically, right? You always mail physical manuscripts.

Yes. Never online. That doesn’t help me. But I’ve never been able to figure out how to send a story online. Besides, it would mean I’d have to type it into the computer and that would be too hard for me. I’ve been working on manual typewriters for so many years. It’s home for my fingers.

Another thing that always shows up in all of your bios is all of these different kinds of jobs you’ve worked throughout your life. Can you tell me about working as an artists’ model?

It didn’t bother me, displaying my genitals for the sake of art. $5 an hour then, good pay if you could hold the pose long enough. And sure, the occasional erection before a class composed solely of women, but all in a day’s work and I’d warned them. It could be the fault of a breeze coming through an open window, or the things that pop into your head when you’re sitting on a stool with your legs spread for 20 minutes. I started at $4 an hour with a jockstrap; the extra dollar came when the class instructor wanted me to model completely bare. It came at a time when I had three jobs at once–substitute teaching for the Santa Clara Board of Education, working as a salesman in the boys department of a Palo Alto department store (The Emporium), and modeling, while still writing every day for an hour or two. It’s not an ideal situation, but one can do that when you’re 29 or 30.

Something that happens when you read enough of your work, and then learn about your real life, is that the two begin to blur together.

Yeah, they do. It didn’t used to be that way… but the more I wrote, the more I got involved in my own life as a situation or as a characterization. It just happened. Even though the stories have imagination, you know, things that didn’t happen to me, the story is sort of about me—what I think, what I do—and then I change it around. But it became more and more like that. When I first started writing, although I wrote stuff about myself, a lot of the stories–which weren’t very good stories–were stories that I entirely made up. For instance, during the ’60s with Vietnam, I wrote several political stories. And they’re not as interesting because they’re not about a person who really lived. Am I making myself clear?

Definitely.

When I write about myself and situations I’m in, simple stories like breakups, it comes with a whole fuselage of emotion. Because I’ve lived it rather than sort of mentally or fantastically lived it. They’re not made up.

With the book I’m writing now, it just comes, it starts with a single line, each story, and then I see what happens. In other words, I let it roll. And so it’s sort of the cross between my interior life and the exterior life that I imagined. People sometimes say, “You write about yourself too much.” I say, “Well, a lot of it’s just made up.” The trick is to blend them in a way where they don’t seem inconsistent or incongruous. I’ve written a lot about my wife and two daughters. Now I only write about my wife and one daughter because the younger daughter objected to being portrayed so often in my fiction. I said, “All right, I’ll just make it one daughter and not necessarily you, but just sort of a blend of the two daughters into one, which is creating a new character, a new person.” And then she came up to me about two years ago and said, “You can write about me all you want.” I said, “It’s too late. He only has one daughter.”

There was the story “Last May,” which is in my first collection, No Relief, and in it, the narrator’s father is dying. And he meets a woman and he fucks her in the hospital room with his father dying in bed. That didn’t happen. I met a woman, her name was Marlene, and we became friends and I think she might’ve wanted the relationship to go further and I guess I didn’t. This is a true story–I got a call from somebody that my book, No Relief, was in the window of the Eighth Street Bookstore on Eighth Street in Greenwich Village, because it had been reviewed in a newspaper then called Soho News, which was a competitor to The Village Voice, and they gave it a great review. This was my first book, and from a small publisher. So I was in the Village and I went to see my book in the window. It was evening, the store was closed. And this is a true story, though it sounds totally made up. I swear to you, this is true. And I turn around and there’s the woman from the story. The book, No Relief, which has an attractive cover, is right in the center of the window with a light. There are books around it but they sort of put it in a central place. And I didn’t want her to see the book, so I stood in front of the book so she wouldn’t see it. Maybe she did see it and we said, “How are you?” “Fine.” “What are you doing?” and so on. “I just came down to buy a book and the store’s closed.” And she went away and I think she was going to school, NYU or The New School, one or the other. So it didn’t seem that she had seen the cover of the book.

I didn’t want her to read the story and see what I did to her. And her mother had died. Her mother had died before my father died. So I felt lousy. And I remember Dina, another woman. Dina, who I lived with for three, four years. She was the female protagonist in Quite Contrary. It had been accepted by Harper & Row. She didn’t want that book to come out because I’d written so much about her. She said, “I’ll let your book come out if you give me the movie rights for one year.” She was a filmmaker. I said, “Okay, you can have the movie rights free.” She never made a movie out of it, but she also was PO’d that I had used her. And then there was Bonnie in California, with her two children. The woman in the title story of What is All This? And she said, would I please stop writing about her? Well, I couldn’t.

I don’t think there’s any writing out there now that depicts so boldly and succinctly, without any reservations, what it’s like to take care of another person. The stories are beautiful and ugly and pristine, all at once. They’re important and I’m glad they exist. Was that ever something that you stressed about, writing about your wife and children so often?

Yes. It stressed my wife, which stressed me, and I remember once when somebody was here interviewing me and he asked her, “How do you feel about being portrayed so often in Steve’s fiction?,” and she said, “I’ve given up trying to get him to write about something else.” Or her answer was, “That’s Steve, it’s obviously impossible for him not to write about me.” And they are important stories because I was very much in love with my wife and she was in love with me and it was such a great loss that I can’t not put it into fiction.

You write about sex quite often. I’d say it’s a major concern in your work. Why? We rarely ever read about elderly people having sex (as if they don’t at all). But that’s something that’s refreshing about reading your later work. It’s still a concern.

How could you write about a relationship without writing about the sex life? I’m graphic without being sleazy. But I try to make it funny or interesting or different, but certainly not sleazy unless the guy is sleazy. I know, I’ve written a lot about sex. [laughs] Sex is a part of life, a very important part of life. In fact, it is life.

What’s a regular day like for you here in Towson, MD?

Well, I get up early because I go to bed early. I go to bed around 9:00, or 9:30, after reading for about half an hour in bed. I get up around 5:30, 6:00. I let the cat out first so he doesn’t shit in the litter box. And even if he does, he wants to go out. So I let him out. I make myself coffee. My entire breakfast is already in the refrigerator from the previous night, so I don’t have too many things to do in the morning after waking up. So I just put the prepared food on the table, which is usually a bowl of fruit and then a combination of granola, kefir, and you know, something like prunes and a salad that I made the day before. I put that on the table, then I go outside, let the cat in, change his water outside, change his water inside, put his food down on the floor. So he’s eating. I go and get the newspaper, which is by the mailbox, and I come back and I read the newspaper while I have my breakfast. And then I go in back, in the bedroom, and I start working or I might turn on the computer. See if there are any messages and also to see if I’ve missed something like some city has blown up the previous night. And then I work for about two, three hours on and off, and I usually take a nap for about a half an hour; rest my back, less a nap than a rest. Then I go to the Y usually by about 12:00, 1:00 and then my day is basically free.

I might do a shop for food, I might do a little gardening, try and clean up the place as best as I could. And then I’ll go back to my work for about an hour or two and by then it’s 4:00. I used to take a run every morning. I have difficulty running so I take a short, sort of fast walk. And so it’s 4:00 or 5:00 and I prepare dinner, which is usually prepared for me by the supermarket that I buy prepared food at. Or I’ll make a rice or noodle dish. I’ve prepared my dinner, which is very slight, and I’ll put it in the oven for 30 minutes, finish reading the newspaper or the book that I’m reading. Just read some pages of that and then sit down in front of the computer. You know a lot about computers?

Not too much.

Because I think mine froze last night and I hope it’s working today.

I can look at it for you but I don’t know too much.

Thank you. And then what do I do? I have Netflix, because my daughters share it with me. They haven’t had any movies that I want to see. And if they do have a movie, I usually watch about a half hour of it. And then I go in back and then I read and I go to sleep and I dream and I get up maybe three times a night to urinate because like just about everybody my age, every male, I have a prostate problem, which is a pain. So that’s usually my day. It doesn’t make a difference if it’s Monday or Sunday. The day is sort of repetitive, but it’s not a repetition that I don’t like. Sunday, I often go to a place that has good soup. And I get a piece of bread with it. It’s called Atwater’s. So I sit at the counter and I treat myself to a soup and a piece of bread with butter on it.

I’ve become sort of antisocial, reclusive in the last couple of years. And I have people who want to see me and I turn down most people. Because it’s become kind of hard. I feel sort of awkward and I’m embarrassed about the way I look sometimes; see my head [points to a cut on his forehead]. I fall a lot and crack my head open a lot and I’m afraid if I see people I might urinate in my pants suddenly. Because it comes on very quickly. And with some people, there’s just a couple of people, like I’m having no difficulty talking to you, but most people I have difficulty talking with and I feel sort of dumb; awkward, wrong words, thoughts are scattered. So my social life has sort of narrowed down to just about nonexistent. I do have one guy writing a critical study of my work, so I see him for lunch. And two couples have been very nice to me and they’re real friends and they would do anything for me. And so I see them about once every two, three months and otherwise I go to the Y.

The Y is a central setting in a lot of your recent stories.

That’s right. I go every day. I haven’t gone today but I will. And there aren’t many people there to talk to, but I like it that there’s some action going on. You know, people are sweating, peddling away feverishly on the bikes. And I think it keeps me relatively healthy other than the things that I can’t cure or make better with exercise. So I do that every day for about an hour; hour and a half.

What’s something that you haven’t done yet that you still want to do?

Well, to go back to Paris, but I’m not going anywhere. Not going to New York. I can’t walk too far. And I don’t want to use a walker. I can’t think of anything. You know, life is too short. Like, I could have been a painter. I did a lot of artwork, but painting came too easy for me, I was too satisfied too quickly… and I couldn’t work on it or I just knew it was right very fast. At one time I was doing that and writing at the same time and I discovered that I had to concentrate on one or the other. So I concentrated on writing. And this was in 1966 or so when I made that decision.

Maybe you don’t care, but why do you think someone should read your work?

Nobody has to read my books. The only thing that’s important to me is that I have something to write. And one reason that it’s important to me, is that if I’m not writing something, if I don’t have a page to go to the following day, I get very irritable with myself. And so I need to know when I stop writing, let’s say today, that I have a page to write tomorrow. Because I always have to have something to write. Frog took me maybe four years to write, four and a half years, and when I finished it I didn’t really have a publisher for it. I only had somebody who was interested. I started something new the next day. Somebody else might say, “Well, why don’t you take a break, give your mind some time to clear.” I say, “Because something will come if I sit down at the typewriter.” And I have lots of one liners that might be good lines to start off a story with, or some concepts that might be a good story if I just sit down and write them. So that’s been the way I’ve written all my life.

Once I started writing books, I’d finish a story and start another story the next day, finish a novel, and start a novel or a short story the next day and this makes me happy. It makes me sort of not nervous about what I’m going to do for that day. In the old days, when I lived in New York and I would finish a story, I would always walk it down to the copy center on 40th Street and Madison Avenue and get it copied three or four times and then walk home, stop at a Chock Full o’Nuts at 56th Street. They had a cream cheese and date nut bread, and I didn’t have much money, so I’d limit myself to a mug of coffee and the cream cheese date nut bread sandwich, and I would go home and by the time I got home I might have an idea for a story the following day. Which I might then start that evening.

Only once–this is a true story–when I was walking to the copy center and that’d be from 75th Street all the way down to 40th Street and Madison Avenue. I’d walk back. Not a big walk. While I was walking to the copy center, I would usually walk on Central Park South because it’s an interesting avenue. And some guy burst out at me. He was in front of the Russian Tea Room. And he said, “You must be famous, could you give me a signature?” And so I told him I wasn’t famous and so on, and so on. I said, “I’m a writer and not doing too well.” He said, “Well, one day you might be famous.” So I wrote my signature, I gave it to him. I walked to the end of the block, continuing on my way to the copy center on 40th Street and Madison Avenue and I got the idea for the story “Signatures.” So I stood there, got a pen–I always had a pad in my back pocket and a pen in my side pocket–and wrote the entire first draft of the story standing on the corner. And then I continued walking and felt very good because now I didn’t have to wait until I got home to start the story, I already had the first draft of the story for tomorrow. I would never then start rewriting it that day. I’d always let it sit for a day and then start rewriting it or making it into a complete story the following day.

What’s a question you wish someone would ask you that no one’s asked you yet?

That’s a good question. Why do I write? I write because what would I do without writing? When I started writing, I didn’t know that this would be my life. That this would be the thing that carried me through all my professions, carried me through life, and gave me the greatest enjoyment. You know, enjoyment not like sex, not like food. Not like good wine. It’s just something to do every day. It became that. It wasn’t that in the beginning. In the beginning, I just wrote stories and they were taken, they weren’t taken. I was serious but not as serious as I am now. And I became more serious as a writer the older I got. So now I am a more serious writer than I ever was.

And another question is, which is my favorite of my books? I guess my two favorite books–I like them all–my two favorite books are Frog and 30. Because I think they went further–at the time that I was writing them–than I’ve gone with any other books. And I think the one I’m writing now I’m going far with. I think the book His Wife Leaves Him also sort of goes pretty far in the chances I took with it. I know a lot of people don’t like the fact that the paragraphs are too long and that there’s no linear dialogue. But I like it, anyway. I like all my books.

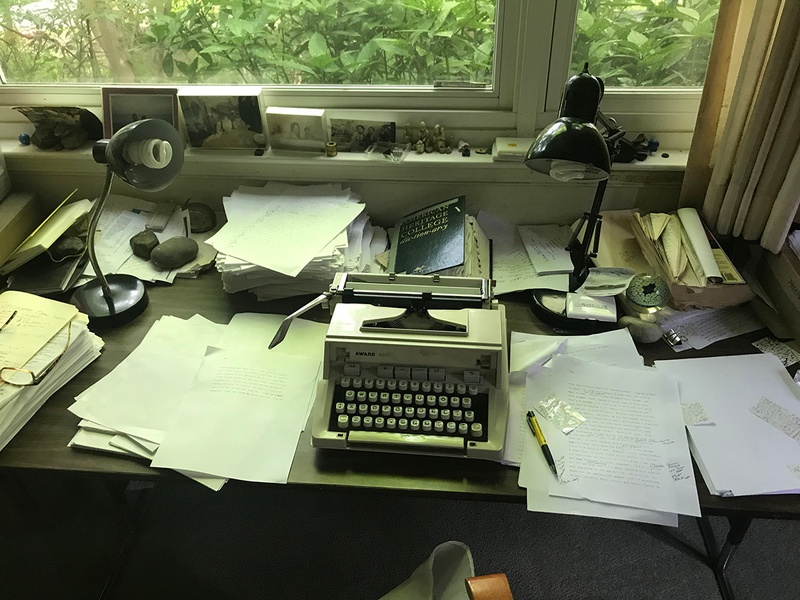

Stephen Dixon’s desk, 2019

A selection of Stephen Dixon’s favorite Stephen Dixon books:

Frog (British American Publishing, 1991)

30: Pieces of a Novel (Henry Holt, 1999)

Late Stories (Trnsfr Books, 2016)

Dear Abigail and Other Stories (Trnsfr Books, 2019)

Quite Contrary: The Mary and Newt Story (Harper & Row, 1979)

Gould (Henry Holt, 1997)

Phone Rings (Melville House, 2005)

Garbage (Cane Hill Press, 1988)

His Wife Leaves Him (Fantagraphics Books, 2013)

14 Stories (Johns Hopkins, 1984)

- Name

- Stephen Dixon

- Vocation

- Writer

Some Things

Pagination