On not being afraid to do a lot of different things

Prelude

Tina Horn got her start as a dominatrix and indie pornographer in San Francisco. About a decade ago, she moved to New York where she delved into nonfiction, writing about pleasure, sex work, and sexual politics for publications like Rolling Stone, Allure, Glamour, and Hazlitt. In 2015 she published a book of nonfiction stories, Love Not Given Lightly, and the following year a guidebook, Sexting. She is also an educator, speaking on topics such as ethical BDSM and masturbation. Horn might be best known for her podcast “Why Are People Into That?” where she’s hosted conversations with all kinds of figures including comedian Margaret Cho, author Jenny Zhang, tattooer and publisher Tamara Santibanez, and writer Merritt K . Now Horn is in the comic book business; the first arc of Safe Sex (SFSX), a thriller about a crew of sex workers battling sex fascists in a timeline where sexuality is bureaucratized and policed and extramarital sex outlawed, just came out as a paperback volume.

Conversation

On not being afraid to do a lot of different things

Writer Tina Horn on the value of DIY, the creativity inherent in sex work, why being a writer is sadistic, 1099's, and always punching up.

As told to Leah Mandel, 4933 words.

Tags: Writing, Podcasts, Comics, Sex, Independence, Multi-tasking, Politics, Collaboration.

You do so many things. What do you say when people ask you what you do?

If I have to use one word, I say writer. I’m quite tired of having to use lots of words to describe who I am and what I do. If I have to use rule of thirds, I will say writer, teacher, and media-maker, then that encompasses some more things.

How did you get to where you are now? What was your first job?

I’ve been a freelancer basically my entire adult life, so I’ve rarely had one W-2 or even one career. I’ve found that even though everybody acknowledges we’re living in a gig economy, there’s still leftover disdain for people who make most of their money on 1099s. It reminds me of the disdain for bisexuals: “You’re a fence traveler. You can’t commit. You’re slutty.” I guess I’m a slut for gigs. But it’s for the same reason that I’m a slut-slut, and that I’m bisexual and queer: I’m not a slut for jobs because I’m a commitment-phobe, I’m a slut for jobs because I’m curious and versatile.

My career began in my early 20s when I started working as a dominatrix in the Bay Area, and that led to being a pornographer. I made a decision when I moved to New York about a decade ago to continue doing the same things I’d done as a sex worker in different mediums. Not because I was disinclined to continue doing sex work; I would do sex work for the rest of my life if I could, but because I wanted to have more options and potentially more longterm stability. The kinds of sex work I’ve done have called upon certain levels of creativity, structural organization, communication, education, political movement building, and advocacy. I’ve figured—I guess because I’m a slut for jobs—“Why don’t I also start this project, and why don’t I also see if I can collaborate with institutions, like major publishers, and try to do a bunch of different things?”

The main things I’ve been doing in the past decade or so have been the podcast and freelance writing. Mostly the same topics I was engaged in as a dominatrix and pornographer: sexual politics, feminist politics, kink cultures, queer cultures. I like public speaking, so I’ve also managed to carve out a niche teaching adult sex education in sex toy stores, and sometimes at colleges, bookstores, and community centers. Writing comics and fiction is relatively new—but it’s the same themes I’ve done in all my other work that I’ve been bringing to the comic.

There are certain things that change when you’re writing nonfiction versus fiction, but it’s essentially storytelling, right? Do you find fiction to be harder, coming from a nonfiction background, or is it just different?

I have a Master’s degree in creative nonfiction writing, so I’ve studied forms of nonfiction that are engaged in the same craft techniques as fiction writing. The note I got most from my editor at Rolling Stone, Liz Garber-Paul, was that I needed to be mindful of when my sentences were “oped-y.” She was pushing me to have the rigor to realize that as a reporter every sentence you say has to be factual. You can have a point of view through the facts you present and the way that you present them. I was very fortunate to learn to write fiction on the job with another great editor who commissioned SFSX and doula-ed the whole project. I really learned how to write fiction by writing comics, and I learned how to write comics on the job of writing SFSX. In my experience so far with writing fiction, which is admittedly limited, the building blocks of the storytelling are just a little more textual and clear.

My favorite kind of fiction is genre fiction: sci-fi, horror, action-adventure, crime and detective fiction, and porn, frankly, which is an interesting combination of fiction and nonfiction—especially filmed porn. The thing that genre fiction has in common with porn, and even the improvisation of storytelling that goes into being a fetish provider, a dominatrix, is that they’re body genres. They’re meant to elicit a response in the body, and that’s when you know it’s working. Nobody can argue with the body. A tearjerker is working if people are crying. Porn is working if people are hard and wet and cumming. Horror is working if people are screaming, their pulses are racing, and they’re sweating. And comedy, of course, is working if people are laughing. Am I going about that in a way that harms people or punches down? Or am I doing it in a way that is also critical of power and punching up, which is what I always want to be doing.

I want to ask you about the podcast. I do not exaggerate when I say “Why Are People Into That” is the only podcast I listen to. Why and how did you decide to start it?

Around 2010, when I moved to New York, I’d been doing this queer kink sexuality video project, and my collaborator and I had a falling out. I decided, “You take it. I have other things I want to do.” At that point, I had so many friends and collaborators and colleagues and comrades who I knew were comfortable talking about sexuality. And they had their own boundaries around how intimate and personal they wanted to be while talking about sexuality.

I knew enough about podcasts to know you could do it on your own and it would be legible. I’m not a technical perfectionist, I’m a very DIY punk. If it’s sloppy, but you can understand it, that’s fine with me. I care more about the vitality of the human expression than I do about fidelity. Doing my own thing means those are my values and I get to decide. If people don’t like it, they don’t have to listen. If somebody wants to be like, “I really like the content of this, but I think that the audio could be better.” Then I will say, “Then you should make monthly donations to me, because that shit takes time and time is money.”

I also just really wanted to. I was putting a lot of energy into pitching articles to major publications, trying to get work in book publishing and other New York media. I was already aware of how much compromise and collaboration, and in some cases concessions I was going to have to make in order to survive and make money, in order to make a name for myself. Humility is good when it comes to creativity, and it’s very important for creative professionals to have experiences where they don’t just get to say, “This is what I think, so we should do it.” But I have plenty of that, and I knew that I was going to have plenty of it, and I was right. I was like, “If I’m going to be putting myself out there in this way, I need to have a thing that anchors me, that is totally mine. Whether it sinks or swims, this is totally mine.” Sexuality and related subjects of kink and gender and love, even, are endlessly interesting to me. There is literally no end to the different topics that I want to talk about. I learned the basics of recording and the basics of publishing on an RSS feed, and I just started it.

Is there a lot of planning that goes into each episode, or is it more organic?

Interview and conversation shows require very minimal production. I love the vitality and exploration of people thinking out loud and working things out in real time. And playing off of each other, whether it’s humor or flirtation or tension or conflict. Sometimes I prepare things I want to talk about it, but a lot of the time I’ve chosen the right people and it’s relaxing to let my mind unwind and bring up stories or pop culture references that come into my head, or an article I read recently, or something happening politically. There’s something really beautiful about what comes out of something spontaneous and not too strictly planned, and not too strictly edited in post. We don’t get enough of that when it comes to sexuality.

Being able to talk through your desires, your boundaries, your tastes, your curiosity, your style with people that you trust takes the pressure off of only talking about love and sex with the people you have romantic love and physical intimacy with. You need to be able to talk about that person with somebody else. So the first thing you need to do is build trust for being able to talk about sex, making yourself vulnerable to your friends.

Probably 75% of my guests are my friends, and some of them are people I play or have sex with, personally or professionally. When I’m hot for someone, it’s very soothing and comfortable for me in the way that I used to be like, “Hey, do you want to shoot a porn scene with me?” Now I’m like, “Do you want to come on my podcast? I don’t have time to date you, but then we can have this connection now.” That’s my big secret. Not true of all my guests. But we’re always doing a certain amount of thinking about, “What do I want to put out there? Who’s going to be listening to this? What is my persona? Do I want to say this thing that is under the umbrella of my persona, my public persona?” But we’re not really doing it for the listener, we’re doing it for one another. I think then people feel like they’re voyeur-ing, and that’s fun.

I say that, but I also want to be very mindful of the fact that it would be a fantasy to say that the presence of the microphone and the awareness of the recorder and the awareness that the conversation is going to be published online for anyone to listen to potentially in perpetuity, and the fact that it’s about sexuality, and a lot of the time it’s about very taboo topics of sexuality—it would be a fantasy to say it’s the same conversation you’d have if the mics weren’t on. In the way that it’s a fantasy to say that porn is like, “We’re just having the sex that we would have if the camera wasn’t here.”

The reality is that it’s labor, making this podcast is labor for me. It’s not mutually exclusive to enjoy your work and for it to be labor. But as somebody who tries to do a lot of work through my creative work and my journalism work of reminding people of the importance of labor rights in formal economies—like sex work, where people hear “sex” and then forget about the work part—it’s really important to assert that the podcast is not the same as having someone over to do a scene. Partially because the business model is different, because I don’t sell the podcast in units the way I would sell a clip, if I had an OnlyFans. But I do make ad revenue, so there’s an agreement between me and the guest that we’re making art through conversation together, and that has its own intrinsic benefit for them. It’s also going to have a benefit for them in the sense of promoting their work, so that people know more about them and will buy their clips or their books, or follow them and buy them a house, or whatever.

How did you get into making comics?

I’ve always loved comics, but I never thought about writing them until I got contacted out of the blue by this editor at DC who had been listening to my podcast, and was like, “Do you want to do a comic?” I was like, “What? Yes.”

SFSX was originally at DC, and then DC saw the first couple of issues and decided not to publish it. I was very lucky that Image was like, “We would love to publish this.” They’ve taken very good care of me. I had written the whole arc, and I’d been connected to a great lawyer who helped me to get my rights back. I got the rights back and hooked up with an old friend of mine, Laurenn McCubbin, who’d done design and editing for Bitch Planet and Moonstruck and a few other Image books. It was great to be able to have a conversation with her about equity, and to start to think of SFSX as a small business that I owned. And the business model with Image, which is different than the business model at DC, is that Image takes a publishing fee and they take care of publicity, distribution, and production, making the physical thing, and a bunch of other shit I’m sure I take for granted that they do. Then it’s my responsibility to make the damn thing and turn it in on time. To coordinate with my lawyer, and with Laurenn, who is now officially the editor and designer, and to figure out what artists I want to have on the project. In our case, the cover artist is Tula Lotay. The change from DC to Image also gave me an opportunity to change course on the artists.

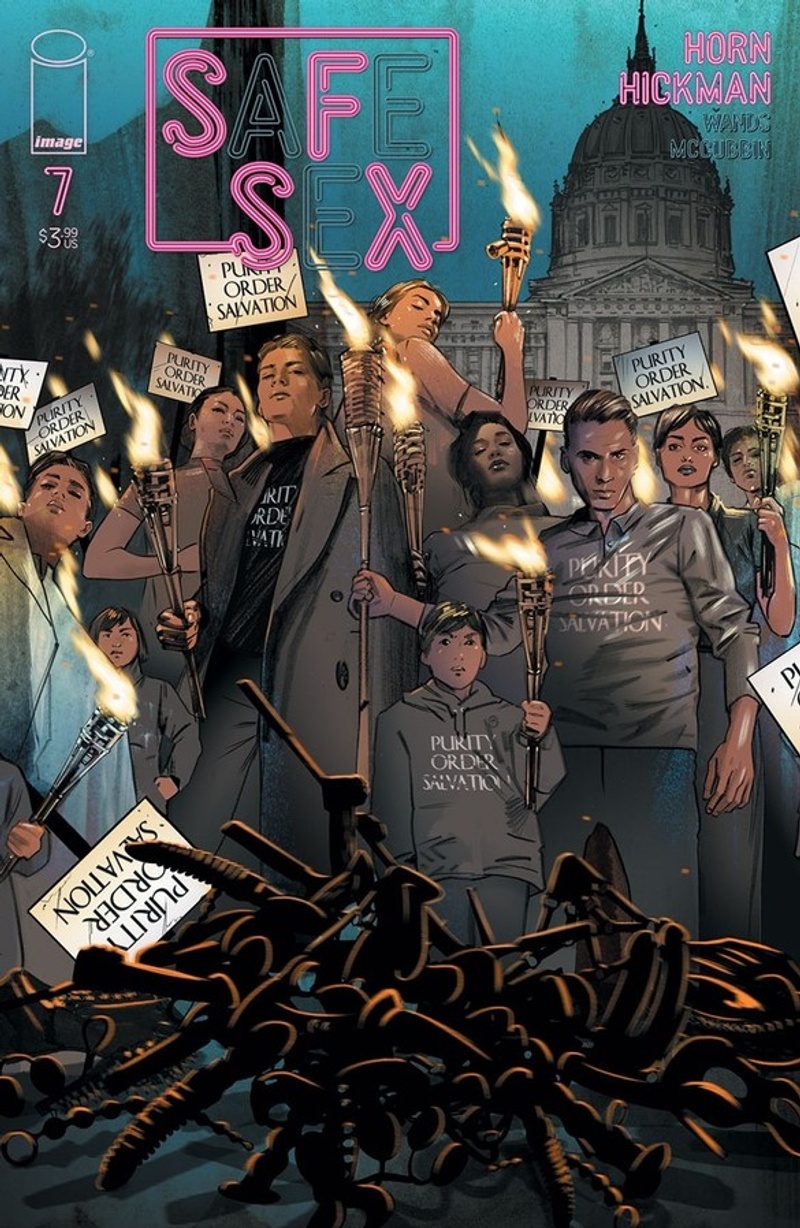

Safe Sex no. 7 cover

That’s why the art is different after a couple of issues?

When DC canceled us, Michael Dowling, who had done the first two issues, got another gig. Dowling’s work is perfect for those first few issues, but it was really meaningful to be able to pivot to the artist Jen Hickman. They are queer and understand the cultural and aesthetic sensibility of this book in a way that, not only do I not have to explain to them, they’re bringing their own point of view to every aspect of their visual storytelling. And, as a small business owner, being able to give work to an up-and-coming queer artist is important to me. Jen’s coming back for next season, issues eight through thirteen. I’m super stoked about that.

Tell me about Issue 3, “Horizontal,” which is a kind of flashback/tangent episode where you get to explore the Dirty Mind (SFSX’s main characters’ headquarters), and is in a more cartoony style than the rest of the series.

We’d been canceled by DC, and I wanted to use that opportunity to totally take control back over the project. I really wanted to work with more queer artists. And by this point I had been to more conventions, networked with more people, and had seen Alejandra Gutiérrez’s work because she is a queer comics artist who’s also out as a sex worker on the same platform. I knew I wanted to work with Alejandra, and it felt really important to me to have her as a collaborator for SFSX specifically, but I didn’t think she was the exact fit for the series in an ongoing way.

It was awful to have been dropped by DC, but I was in an open-minded, liberatory space. Like after you get dumped! Like, “I could fuck anybody!” By that point I’d written the whole Protection arc. I felt so good about the whole story and all the character arcs, the world-building and everything. But one thing I wanted to do was spend more time at the Dirty Mind. When it’s a thriller there’s only so much you can do to stop and show a variety of different kinds of sexuality. Those things totally clicked in my mind: “Now that I am not limited by the more conventional constraints of DC, and I wanna work with this person, why don’t I write a capsule episode?” I also love fucking with chronology, and it gave a signal of transition: “Now that we’re at Image, we’re gonna be experimental with the visual style, we’re gonna try different things.” Working with Alejandra was so refreshing—not everybody can be really erotic and really funny at the same time.

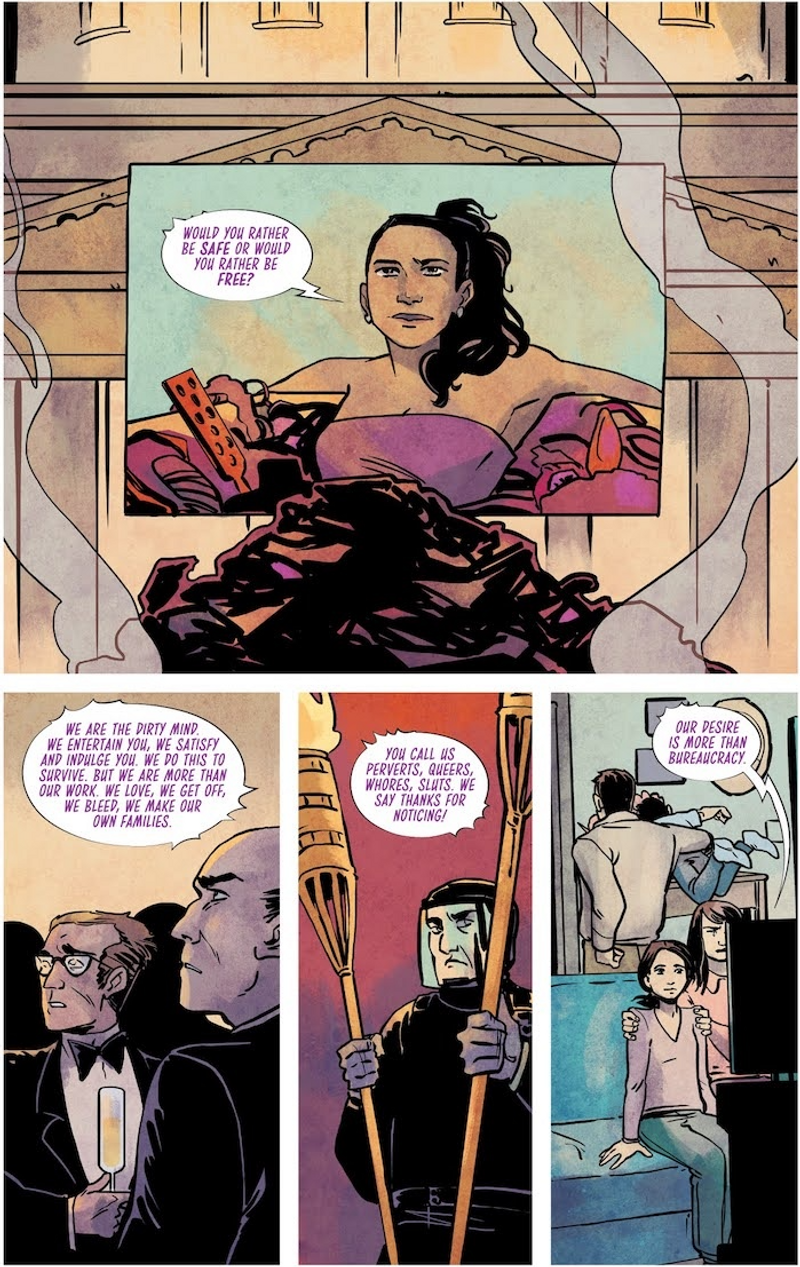

page 12 from Safe Sex No. 7

The toilet play cel—“In case you want to be a toilet”—I almost screamed.

I told Alejandra I wanted them going through all these fetish-y rooms—a Wet and Messy room with some lube wrestling going on, and maybe we can have some fetish gear, and let’s have a femme character, and make sure we have beefy male characters, and then let’s have a toilet room. I said to her, “In this room, people are giving golden showers.” She has both the fluency in kink to the point that she would understand what that might look like, in a sexy way, and also to understand the inherent humor of toilet play. It’s so funny, so colorful and sexy at the same time. I’m very proud. That’s the beautiful thing about making comics. It’s like songwriting with a band, or with a collaborator, in the sense that you might write the melody, or the lyrics, or the structure of a song, but the way the song actually ends up that you jam out through collaboration with the other musicians you’re making it with and creates something bigger than the sum of its parts. And you have this very special kind of pride that is alleviated from feeling too self-involved. “I’m proud of us.” This thing that came out of the spirit of our collaboration, and that feels really good.

You’re like the Dirty Mind crew. They’re a team and each contribute their special skills. For instance, when they use rope to help them climb through the air shafts, or when they’re trying to escape and Sylvia dumps the vat of lube.

That’s a good example of what it was like to write a heist-jailbreak-thriller-pseudo-superhero-dystopian story. My original editor gave me the advice that the way you figure out how characters are gonna get out of the shitty situation that they’re in, especially as a team, is: What makes each of these people special? That if you lost them, the team would be fucked in a very clear way. If you’ve got the Ninja Turtles: if Donatello is indisposed then you don’t have anyone to come up with the tech. If you lose Leonardo then you don’t have a leader. What makes sex workers special? What makes queers powerful? What makes kinky perverts unique in how they think about the world? The average person in a deserted storage space filled with the remnants of what used to be a sex dungeon is probably not going to think, “I know what’s in this barrel, and I know what it can do.” But a kinky sex worker is probably gonna be like, “I am familiar with the properties of silicone lube and I know what will happen.” And to think, “This is how we fight the oppressor: with lube,” is the fun about writing fiction. You set yourself up to think of those things, and then you can delight yourself and others.

I also love George’s line, “You forgot I like it,” during one of his torture scenes, for that reason.

I really put George through the ringer in this story. At one point Jen Hickman and I were going over Issue 6; I was looking over everything I’d done to George and I was like, “I really want George to binge Schitt’s Creek and give him an edible and a gravity blanket for like a week. Poor guy.” But the idea that, as a masochist, he’d be able to get himself out of a nonconsensual situation because it makes him more powerful that he knows what to do with pain and how to process physical pain, was a narrative I wanted to play with. I also wanted to have a moment where you think there’s catharsis, with him escaping. Those moments are so cruel. Being a writer is sadistic. I do these cruel things to these characters!

I enjoy pushing the limits of my body and other people’s bodies in a way that we can experience breaking through barriers, or approaching destruction, or entropy, or coming apart in a way that is ethical and mutually agreed upon—and how we want to be put back together. Those experiences are at the core of my erotic identity. If I had to pick the top three thesis pages of the Protection Arc, this is one of them. In this moment of George’s near-escape, I wanted to give him a little bit of the thesis of the difference between consensual and nonconsensual pain, and consensual and nonconsensual power exchange, and what people who are not kinky don’t understand about what it means to consensually play with pain and power. Also, this idea of, what do you do if you’re trapped inside of pain you didn’t ask for? I have been in relationships that went from consensual sadomasochism to abuse, and understanding the difference between those things is very important. I tried to sneak that into this creepy story.

As Jones says in Issue 6: “Feeling safe isn’t the same thing as being safe.”

That is one of the other big thesis statement moments. I think that’s the villainy of the story that you see represented in Boreman and Powell specifically, and in the party more generally. Boreman and Powell both being people who throw more marginalized people under the bus and construct sex workers, trans people, sluts, or perverts as the deviants that need to be reformed or reprogrammed so that feminists and homonormative white gay men can have more rights and more respect. The idea that you can protect yourself from stigma and oppression by oppressing and stigmatizing others, essentially so that you will make yourself safer by making other people less safe. And that if you feel safe, you are safe is a wrongheaded notion behind a lot of things that are off in our culture. That people are not actually fighting to be safe, they’re fighting to have the idea or illusion of safety. And that people don’t care if they are actually safe as long as they feel safe in the moment.

You can feel that way in relationships as well. You can feel safe even if you aren’t actually safe. I want to talk more about the villains. I love that Boreman is this white lady feminist, and everything she says is like, “Well, feminism.” Basically: fascism under the guise of feminism. How did you come up with the idea for her as a central villain?

A notion I came up with really early on was people who could be allies to our heroes. Our heroes are the most sexually marginalized people in society. The people who, for all sorts of intersectional reasons having to do with class, race, gender, orientation, and identity are the most marginalized. Boreman is a feminist. Feminism is not a monolith. I identify as a feminist and I could be on a panel with someone who identifies as a feminist and we could have the literal opposite ideas of things that are extremely important to us. I’m right and they’re wrong, of course, and Boreman represents the wrong person, that I might be on a panel with—that I have been on a panel with. Exactly as you said: white feminism, second wave feminism, the Aunt Lydia of Handmaid’s Tale, the people who have found commonality—Catharine MacKinnon being the perfect example—with the religious right in being anti-porn.

That, coming from sex work and nonfiction, informs my fiction writing. I’ve studied how people think and how other people think about what those people think, and how other people think about what those people think about what those people think. And it is a chance to, in a petty way, which I will totally admit, villainize. It is quite cathartic. You’re finding these people in the discourse all the time and it’s like, “You’re autonomous human beings, you’re allowed to have your own opinion—but you’re wrong.” And then you get to put all of their words in the mouths of these villains, and you can construct them as misguided.

Same with Dr. Powell. [Pete] Buttigeg is very much like Dr. Powell. He is a white cisgender gay man who, in his public persona, is putting out this anesthetized version of gay male sexuality. “We’re not gonna talk about icky butt stuff, we’re not gonna talk about venereal disease, we’re not gonna talk about leather. We just want the same things that you want.” Buttigieg is a very good example of this homonormative effort to be like, “Marriage is the most important right that we need. Employment discrimination? Who cares.”

I want to show the Party as this monolithic organization, and how they activate these people who have so much to lose, because if they get associated with the perverts they’re never gonna get any rights. But if they’re given the opportunity to align themselves with moral purity, values, etc., they’ll throw their fellow queers and feminists under the bus, they’ll throw sex workers and perverts under the bus in order to get that. What I wanted to show through what happens to Boreman and Powell is that it doesn’t work. Because those people are liars. The name of Issue 3 is “Horizontal,” a reference to horizontal violence. If we’re doing the work of the oppressor for them by fighting each other, they can just put their feet up. That is what I really believe about the way power works in America.

Tina Horn Recommends:

N Joy Pure Wand: a stainless steel insertable toy for any hole that will change the way you think about penetrative pleasure.

Hathor Original Lubricant with Horny Goat Weed: a lube so essential I once sold it to Beyoncé!

Phantom Thread: the only movie about BDSM ever made.

Fistzines: DaemonumX is keeping leather dyke zine culture alive with this series.

A self care ritual: find a movie theater an hour walk from your home. Eat 5 mgs of THC as you leave the house. Come up as you enjoy walking across town. Companion or headphones optional. Snacks to your taste but not optional. Peak during the movie. Come down while walking home. Read a book in an epsom salt bath and cum if you like. Sleep for nine hours and don’t wake up to an alarm.

Randy Newman might seem off-brand for me, but he is one of the great ironic storytellers, someone who taught me how to portray characters (fiction and nonfiction) that are telling you something different than they think they’re telling you. I missed the Oscars this year because I was getting my ass beat on-stage at the MoMA PS1 dome for Kink Out: Spaces (missing the Oscars is very off-brand for me). We all went out to dinner after the show and as I sauntered in a sadomasochistic/red wine haze through this Italian bar in Long Island City, who should be playing a song from Toy Story 4 or whatever live on a giant HD TV, but my man Randy! I exploded in rants about his genius and had to be stuffed into a Lyft.

The Low, Low Woods, a new comic book series written by my favorite queer fabulist Carmen Maria Machado and drawn by my favorite horror artist Dani. Really right on about ‘90’s gay teenage bedrooms, and the sinkhole inside of us all.

Exchange audio recording of yourself masturbating/talking dirty with your dates or partners. An exercise in building erotic intimacy, creativity, and trust. Great for a headphone subway energy boost!

Frexting: sexting with your platonic friends. You need someone to talk to about sex besides the people you’re having sex with, people! And you need bros who will tell you your balls look great.

The music of Pose: What’s not to adore about this show? (I got to consult on the dominatrix scenes in Season 2!) Growing up a total rockist, I foolishly dismissed most pop as superficial. It wasn’t until I lived in New York City as a queer slut that I felt the throb of disco in my joints and understood the importance of this music to my history and culture. There’s some excellent compilations online.

Get In Trouble by Kelly Link: just mesmerizingly, jaw-droppingly gross

Yo Is This Racist? I love any advice show or columns for the same reason most people like reality tv, and this is my current fave. Thoughtful, loose, quick, it’s proof that the best way to fight oppression is through irreverent storytelling, not proscriptive rules.

Foam rolling: solo play for masochists

Ariana Grande ponytail flip GIFs: good for any occasion

Fairway Rotisserie chickens: get ‘em while you can!

Dark leafy greens will never go out of style…

Cranio sacral massage: a lesson in surrendering to the subtle body.

Amaros: bitter, and somehow witchy?

Lessons about friendship in Buffy the Vampire Slayer: these have aged remarkably.

Buying porn directly from the porn stars who make it: the Farmer’s Market of adult entertainment!

- Name

- Tina Horn

- Vocation

- Writer, teacher, media-maker

Some Things

Pagination