On responding to negative feedback: Walking with a broken foot

Prelude

Amy Klein is a poet, writer, and songwriter. Her unique background blends punk with literature. A graduate of Harvard’s creative writing program, she has played guitar in several bands, including Titus Andronicus, and she currently leads her own band. Her sophomore album, Winter/Time, recently came out on Don Giovanni Records. Amy is currently at work on a novel in verse. She has received an Academy of American Poets Prize, and she was named one of Ten Women Music Writers to Read Now by NPR.

Conversation

On responding to negative feedback: Walking with a broken foot

Musician Amy Klein offers strategies for learning how to filter out negative feedback, rejecting the idea of making “good” art as an objective goal, and believing that what you do as an artist actually matters.

As told to Amy Klein, 2527 words.

Tags: Music, Process, Adversity, Mental health, Identity.

I have frequent dreams and nightmares. Last week, I dreamed I was walking down a long, narrow boardwalk beside the ocean. My friends were running ahead of me, on their way to a party at the end of the boardwalk. The group was sharing jokes and plans for what they wanted to do. Every so often, I would see one of their faces turn around and look back at me in the darkness. I tried to catch up with my friends, but the faster I walked, the more my left foot hurt. As the distance between me and my friends grew wider, I realized that my foot was broken. It would only hurt me to try to run with a broken foot. So, as my friends disappeared, I let myself walk very slowly down the boardwalk alongside the ocean.

When I woke up, I thought I knew what the dream was about. It was a validating message: We all have to move at our own pace. I was working on healing while others seemed to be moving forward in life. It was alright for me to take longer to reach certain milestones—growing up, getting married, having kids, writing a book, or achieving my dreams. I was busy healing brokenness inside me. However, this morning, I realized the dream was trying to tell me something even deeper. What the hell was the boardwalk, and why on earth was I on it?

I know what the boardwalk represents. It is the life we know. It is the life we have been given. But why wasn’t I walking towards the ocean instead? I could have conceivably walked in any direction. Were all my friends even walking somewhere together, or did I just perceive them that way, as a group of similar people walking a singular path in culture towards a rewarding destination? Was there even a destination? I couldn’t see it, and so, did it really exist?

The reason I bring this anecdote up is that I have been asked to write an essay about responding to negative feedback. And as an artist, nothing has been more damaging to me than the sense that there is an objective reality. Believing that there is somehow a “right” way of being has made me feel less than others in nearly every situation in which I am required to be. For example, walking into the show, I might have the sense that the other performers exist on some higher level than I do, and that they are looking at how “good” I am at what I do, comparing me to some shared standard of goodness which I now realize does not exist. For many years, I have dismissed my own creativity, thoughts, feelings, etc. as not being good enough, which has led me to keep most of what I feel, think, and create to myself.

The second reason I bring up this anecdote is that we exist in a political moment when an authoritarian leader seems to have the power to create reality as easily as firing off a tweet. This so-called “reality” is in fact a warped view rooted in an individual’s narcissistic fantasy. Nevertheless, countless people believe that when Trump calls immigrants “violent,” they are indeed violent and therefore deserve to be punished. I read an interview with Judith Butler today where she talks about executive speech acts—namely, the power to make something real by speaking it—and how Trump wields his speech like a king. The other people, of course, besides narcissists and kings, who have the power to create a new reality through the force of their individual expression are artists. And what I fear most about this moment is that the very people who possess the most power to reshape reality for the better are the same people that our system marginalizes and disempowers through what I would call “sustained negative feedback.”

So, this essay is for artists, but it is also about having courage. It’s about how you can stop internalizing the narrative that you should shut up. It’s about how you can resist that narrative.

Define your own journey.

Which metrics do you want to use to measure your success? And what path do you want to explore?

The most useless feedback I ever received was in graduate school when someone told me, “Don’t take this the wrong way, but I think you should write less like you.” Now, I understand what he was getting at. I had written something unusual, and he didn’t get what I was talking about. I probably didn’t get what I was talking about either, or else I didn’t know to begin with. But the fact remains that I had a style of writing, and it was unique. Uniqueness is what a good teacher or peer tries to cultivate in you.

Since that day, I have used that quote as a litmus test to evaluate all negative feedback I receive. I ask myself, “Does this feedback help me get closer to myself?” If yes, then I take the feedback to heart and try to learn what I can from it. If the feedback distances me from myself, then I disregard it, just as I disregarded that guy’s point of view.

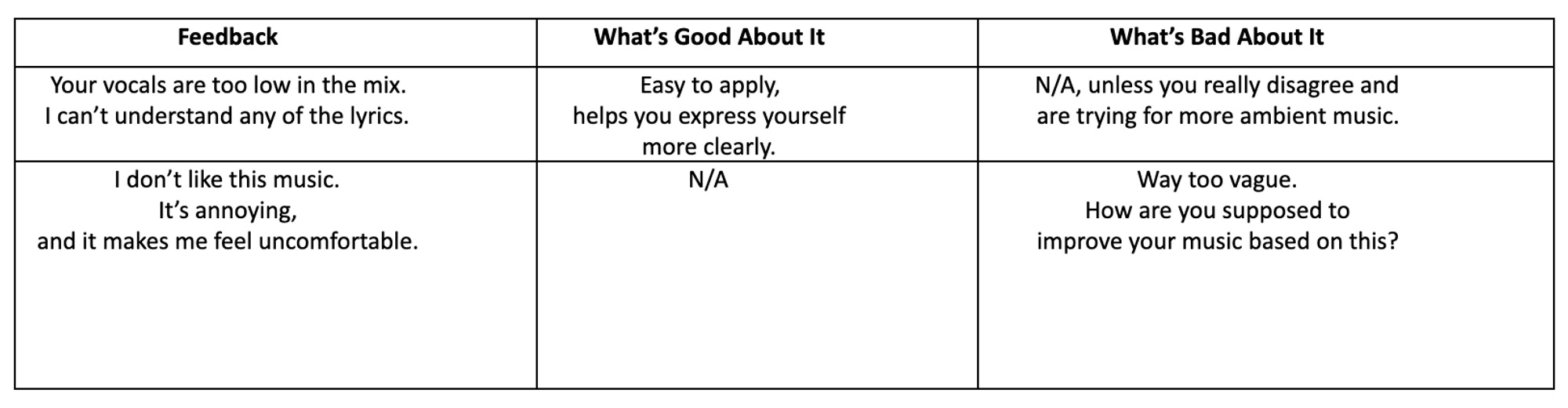

As artists, we have the freedom to evaluate the feedback that others use to evaluate us. To evaluate negative feedback, I typically use the criteria of the business world and ask myself whether the criticism is specific and actionable—meaning, are the instructions clear? Can I apply them? If I cannot apply the feedback to create a clear change in my work, a change which moves me closer to my own vision, then the feedback is not useful to me. Here is a chart of good and bad feedback:

In order to decide which feedback you want to consider, it is very helpful to first define your goals, not the goals of someone else. I have determined I belong to the category of artists who aim to piece together who they are and what they feel over their lifetimes. My art is about feeling, and my life path involves using art to become ever closer to the self that is buried deep within me. So, now that I have defined my journey in these terms, I can apply feedback which helps me reach milestones on my journey.

Think my music sounds tentative? It’s not so great to hear, but I’ll take that feedback into consideration because being tentative is not what I want to do with my life. Getting more confident expressing myself is something I’m working on—and that’s why I’ll listen to that feedback, not because of who said it or for any other reason.

The more experienced I get at making things, the less I am interested in the concept of “good” art. Instead, what I am interested in is authenticity. To me, “good” art is bound by notions of taste and class and technique. “Good” may be a restrictive concept. What I search for in myself, and what I admire in the art I relate to, is the sense of a unique experience, deeply lived. To me, DIY music cultures that emphasize collective empowerment over notions of “good art” have been more freeing and educational than many environments in which I have studied artistic technique.

When you feel power, it is because you are creating the path that has not existed before. Strive for authenticity, and you will create a vision for your life that no one can destroy. Suddenly the other paths, the ones you think lead towards fame or certainty or truth, will be a lot less important because they are not yours.

Understand the difference between negative feedback and violence.

Whom do you accept feedback from? When is feedback an active attempt to silence you? How can we better support people who have experienced violence and silencing?

One of the worst pieces of criticism I received was when my manager called me a whore in a business meeting. Obviously, I wasn’t in the business of whoring in the meeting. It was a clear-cut case of sexual harassment. I have learned a lot from this experience, although I hope never to repeat it.

The first thing I learned was how hard it was to speak. In the moments after this comment was made about me, I literally felt as if I had no voice. I felt frozen, as if I couldn’t move, let alone open my mouth.

In retrospect, what I remember most, however, was the feeling of gratitude I experienced when someone else in the group validated my reality. As I sat there, pinned to my chair, the man sitting across from me said, “That’s when you say, ‘Speak for yourself!’” In other words, this man I had never met was directly telling me how I could tell my boss to stop. I took a deep breath and told my boss, “I’m nobody’s whore.”

I don’t think it was a coincidence that the man who spoke up for me was Black—the only Black person in a meeting full of white people. His response to the moment of harassment was so quick and helpful—“That’s when you say…”—that he seemed like he had more experience in defending himself and other people than I did. He also seemed more willing to call the B.S. in the room when he saw it than everyone else, who by their failure to react seemed invested in perpetuating the idea that the system was proceeding normally. Either way, his words gave me the feeling of what was possible.

I bring up this simple anecdote about how silencing works and how to disrupt it because every day, voices are silenced in much more complex and harmful ways, often as a result of underlying attacks on specific identities. In calling violence what it is—violence—we allow ourselves to respond to it creatively.

What does it feel like when you send your memoir of immigrating to the U.S. from Mexico to publishers, only to be told that your story isn’t relevant for “everyday people?” What does it feel like when a fictionalized first-person narrative of being a Mexican immigrant, written by a white woman, becomes a major bestseller the next year? This is a form of silencing. To persevere as artists requires collective resistance against racist and capitalist institutions.

Ultimately, I think what I learned from the man speaking up for me in the business meeting was that I have the power to speak up for someone else, too. I am more aware every day that we have the power to create trust within our communities through everyday acts of listening, empathy, and support.

Being an artist, for me, is a command to pay attention to what is happening around me, to notice who gets to speak, and who does not; it is also a command to listen to, and to put my trust in artists whose experiences are different from my own. I believe that by truly listening to and supporting each other, we can begin to replace toxic institutions with deeper forms of connection.

If you are feeling down on yourself and your abilities, it may be useful to recognize that your feelings may be a response to ongoing social and economic rejection, and this rejection has nothing to do with your value as a human and an artist. If you receive a significant amount of negative feedback, it may be helpful to remember that you could very well be a brilliant artist living in a racist and capitalist society. In other words, you deserve to live in a better environment where you don’t have to change yourself.

If you are receiving feedback that is troubling, one way to counteract it is to ask a friend or a collaborator to give you feedback on your work instead. Someone you trust is much more likely to identify aspects of your work that resonate and help you make progress towards your goals. Doing this active outreach when you feel scared and shut down can be very frightening, but it can have remarkable benefits when you ask the right people; they may tell you that you are awesome, that you shouldn’t give up, and also suggest areas where you can improve in helpful ways.

Remember that art is play.

What does it mean to get better? Isn’t this just about love?

Art exists in time, and we are always moving. In capitalism, it is tempting to believe that everything needs to happen now. But art isn’t about the object, however much we may become attached to our songs, our books, and our paintings. Art is a process of play. And when we want to get better, we need to give ourselves permission to play—to enjoy the act of playing, and to take it seriously, the way some people take their jobs.

I feel a persistent sense of joy and embodiment when I play music that motivates me to continue, however many bad reviews I receive. When I felt bad about myself for getting bad reviews, I stopped reading reviews. In the mornings, when I wake up feeling overwhelmed and scared, I like to take out my guitar and just play and sing—with no idea in mind, and for no one but myself. It took me many years to learn to do this.

When I feel a sense of loss and disconnection, it’s often because I’m too attached to what other people think about my work, and it’s threatening my underlying connection to myself. Maybe what it means to take yourself seriously, in addition to having the courage to speak up and put your work out into the world, is being willing to sacrifice anything that threatens your love, your freedom, your ability to play.

It’s true that on many days, I wake up thinking that I’m a failure and decide I should just do something more rational with my life. However, something always stops me from doing it—the next day, I have a band practice where I feel like I’m making progress, or I have a show where I feel happy on stage. Isn’t that radical? To believe that I deserve to be happy? And to believe that my bandmates, my friends, and my fellow artists deserve to be happy too, even if we aren’t successful under capitalism?

When I think about art, I always return to the concept of time. Art is a process of making meaning of our lives, which are processes of change. I can feel a sense of achievement when I reflect on a project I’ve completed and think about all the things I’ve learned, asking myself what I know now that I didn’t know before. Dreaming of the next thing I’ll write or the next album I can make, this is what sustains me through all of the pain and fear of being alive. Making something imperfect is how I imagine that I can grow. It’s about hope, isn’t it—believing that, against all odds, what we do matters?

- Name

- Amy Klein

- Vocation

- Musician, Songwriter, Poet

Some Things

Pagination