Alfredo Salazar-Caro on learning the right things at the right time

Prelude

Born in Mexico City, Alfredo Salazar-Caro is a multimedia artist who lives and works between Mexico City, New York, and the internet. His work exists at the intersection of portraiture, installation, documentary, virtual reality, video, and sculpture. Together with William Robertson, Alfredo conceived of the Digital Museum of Digital Art, a project that functions as a virtual institution and a virtual-reality exhibition platform dedicated to the promotion and distribution of new media art. Here he discusses the VR institution’s beginning, his responsibility to it, and its unfolding future.

Editor's note: On May 17, 2018, Alfredo will be hosting a pre-release preview of DiMoDA 3.0 in Williamsburg, Brooklyn as part of TCI's event series with National Sawdust. Learn more here.

Conversation

Alfredo Salazar-Caro on learning the right things at the right time

The co-creator of the Digital Museum of Digital Art discusses the VR institution's beginning, his responsibility to it, and its unfolding future.

As told to Willa Köerner, 2491 words.

Tags: Art, Technology, Curation, Games, Beginnings, Collaboration.

How did you come to start a museum based in virtual reality?

The short answer is: because there wasn’t one already. It was really a direct result of my creative process, and the scenes that I was involved in. I was doing a lot of audiovisual stuff at the time, like live performance, using Unity and using video game engines. And there just wasn’t a space to show that kind of work anywhere.

Chicago had an underground scene where a lot of people who were into weird computer stuff would get together and show each other’s work, but there wasn’t a space dedicated to it—not anything official within the art world. So that was the impetus, and that’s why I was like, “This has to be born.”

Why did you feel like it was something you had to take upon yourself to create?

I don’t know. It felt right, and I just chased it. You know what I mean? And now that I created it, I have a responsibility to it.

But I shouldn’t say I created it, because it could have only happened through collaboration and the support of many people—especially William Robertson, who co-created DiMoDA with me, and who built the infrastructure for it to exist. After we made it into what it is now, there’s a sense of responsibility to keep it going and keep bringing interesting, diverse work into the space. Whereas in the beginning, it just felt like, “This is a cool thing to chase. This is something that needs to exist.” Back then it had less of a mission, and felt more punk.

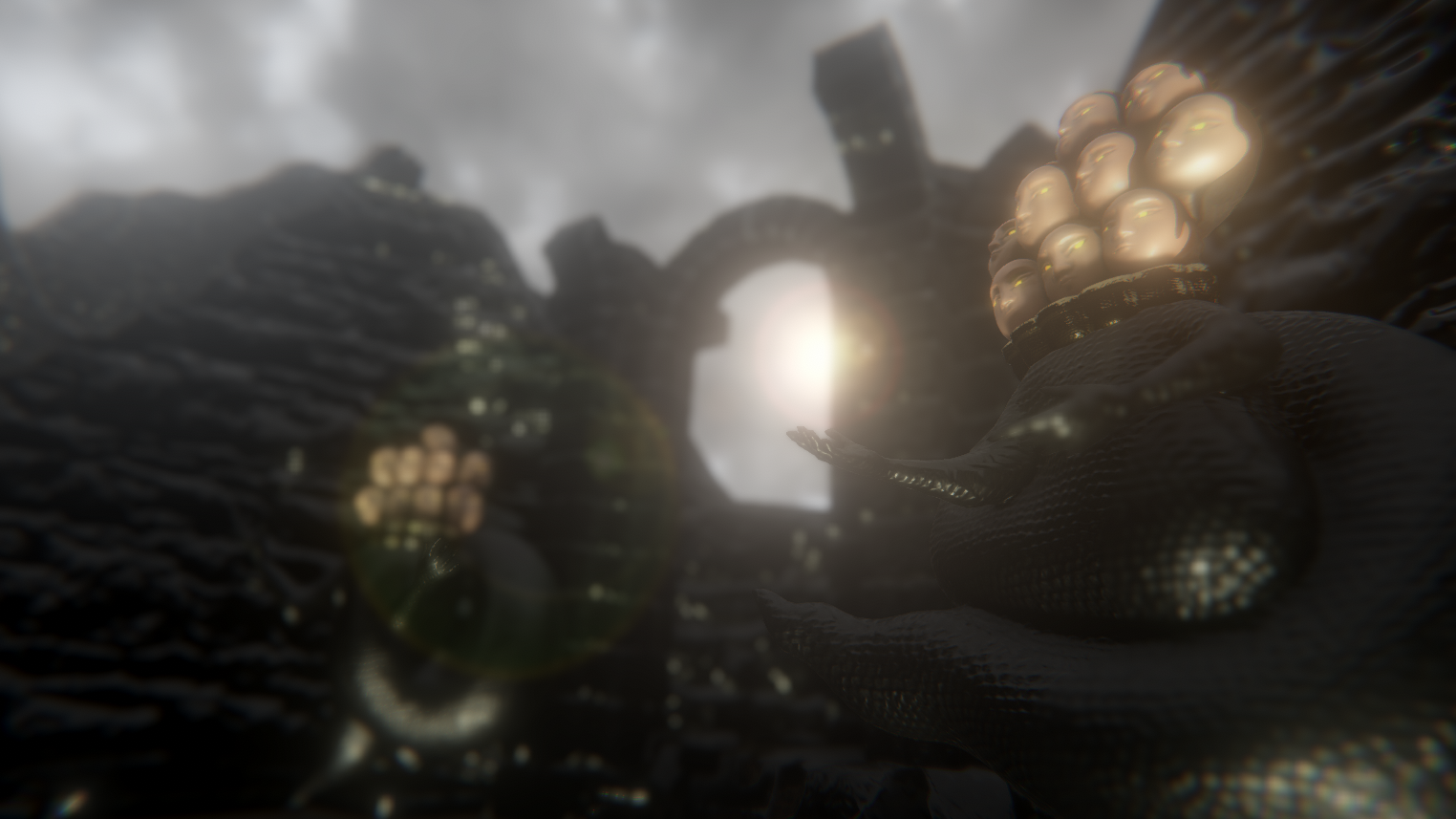

DiMoDA 3.0

What has it been like learning to make things in VR, since it’s such a nascent medium?

To me, it feels really good. My background is in installation and sculpture—real physical stuff. I’ve always been thinking spatially, and a lot of what I was wanting to make back in the day was just physically impossible. I would try to come as close as I could with the medium that I had in front of me—with clay and stone and wood.

But with VR, I can actually take those impossible ideas and make them into something that I can tangibly witness, whereas before it was all in my head. For me, it just feels like a perfect continuation of what I was doing as an artist, as a sculptor.

How did you actually learn to create in VR? I’m curious about the learning curve there, since it’s really only been around for, what, five years?

The idea of “virtual reality” has been around since the ’50s, but the technology to create it has only been available to us as artists since around 2013. I accidentally got into new media because I was taking a class called “Prehistories of New Media,” taught by Paul Hertz, an old-school new media artist, at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. When I signed up for the class, I thought that “new media” meant new materials or something. I had no idea that it meant computer art. So I started going to this class, and I was really, really confused at first. But then I got totally hooked.

That class led me into 3-D modeling, and then 3-D modeling led me into video game design, using Unity and stuff like that to make artworks. That gave me a direct entry point to VR—it was just a matter of the VR technology becoming available. Once it became available, I jumped on it as quickly as I could, and I started making stuff.

Did you teach yourself, or did you take classes on all these things?

With VR, I mostly taught myself. It was so new that being self-taught was the only way to figure it out. Even the teachers that we had around didn’t really know what to do with it—they were experimenting at the same pace that we were.

Before that, most of the people working in VR were working in scientific labs, that kind of thing. There were some really cool VR experiments back then, but they were extremely expensive and prohibitive to share. But then Oculus and other types of VR headsets started coming out, and it made it possible for everybody to jump on it.

How has the actual experience of creating DiMoDA differed from what you imagined the experience might be like? Were there any obstacles, or things that you just couldn’t have predicted when you were starting out?

It’s definitely a lot bigger than I ever thought that it could be. It started as more of a fake museum, or as a form of institutional critique. And then it slowly started becoming a real endeavor. At some point it felt like, “Oh shit. This isn’t just another piece of art anymore. I have to have people to help do things and I have to have an organization and I have to think about planning three years ahead.”

Now we’re at the stage where it’s like, “Okay, we gotta incorporate, and we gotta have salaries, and we gotta think about where our money’s going to be coming from.” What started as an artist project has expanded into a tangible enterprise, and we weren’t really expecting that. I mean, I knew that it had that potential from the beginning, so it’s quite nice to see it grow into this tangible thing.

Can you talk more about this idea of responsibility—about this feeling that because you started it, you have a responsibility to keep pushing it forward?

Responsibility is an interesting thing to bring up because it’s hard to tell: what is my responsibility? If I just dropped out right now, could DiMoDA survive on its own?

For me, it’s important to understand that virtual reality, augmented reality, and all these other nascent technologies that are compatible with each other are creating a new world. In this new virtual ecosystem, people are going to be able to experience each other socially, buy things, and even become other things. So since our society is moving in that direction, it’s important to establish good precedents while we have the chance.

It’s not very often that a generation gets the chance to write its own future, and unfortunately, I think the future of what VR can look like is currently being commanded by a lot of industry-based San Francisco types. Because of this, I think it’s important to start setting up alternatives as soon as possible. In a way, that’s the responsibility: to propose alternative views, alternative content, and bring people to the table that would normally not have a seat in writing the future.

Morehshin Allahyari for DiMoDA 3.0

As you’ve worked to build DiMoDA from the ground up, what things, ideas, people, or resources have been the most helpful?

People, for sure. There’s no way that I could have created DiMoDA alone. I’ve mostly taken the role of DiMoDA’s main representative at this point, but none of this would be possible without William [Robertson]. I’m also incredibly grateful to the people who, from the very beginning, have seen this as something that has potential and momentum, and have pushed us along. Also, the team of people that I’ve assembled to work on DiMoDA really believe in the vision, and are passionate about making it work. And, of course, because of the artists. Their work is what makes this project great, because obviously without it, it would be nothing.

How did you get the artists involved? At the beginning, I’m sure you didn’t have much to show them, because you were just starting out. How did you convince them to work with you?

Our first exhibition was mostly with people I was close with. Claudia Hart is one of my mentors, and she’s followed my work since I was in school. She knows me and trusts me, so when I told her that DiMoDA was something I wanted to do, she was willing to put her name on it. And then she brought along a few other artists, because they trusted her. There were also a few friends of mine from Mexico City who have a virtual gallery galled Gravity.

Not to sound like nepotist, but I’m often friends with people because I really admire their work. Personal relationships are what fuel this thing. As we move forward, we’re also inviting curators to bring in their networks. So the next version of DiMoDA will be curated by Christiane Paul. I have no idea who she’s picking, but I’m sure she’ll bring in really great artists.

How do you keep things moving? Do you feel like you’re constantly pushing DiMoDA forward, or do you feel like things just evolve organically as you go?

It’s a little bit of both. The analogy of being a captain of a ship is really good, because with a ship, you’re subjected to the will of the sea. But you also have a chance to move the sails around to catch the right winds.

So yeah–it will move on its own, but you gotta push it, too, you know? Honestly, I’m really inspired by my Sims. I send my Sims to work every day, and I just check in on them after work. My Sims have really good careers. I’m like, “If you guys can do it, I can do it, too.” They honestly make me want to be more productive.

But in reality, I’m motivated to see this through. For me, working on DiMoDA is exciting, and it’s what I want to do. Also, it’s nice to be able to drive a project that’s not just for me. DiMoDA is for everybody. I love using my energy to showcase other artists and to bring work to people that normally wouldn’t have a chance to see this kind of stuff.

At my core, I’m an artist. So for me, this isn’t just a virtual museum—it’s a piece of conceptual art. We’ll see how long it can exist as that. And as it continues to become something more “institutionalized,” it still allows me to fulfill some interesting passions.

How integral is the VR component to what you’re creating? Could you see the idea evolving and existing far into the future, when VR might be obsolete?

100%. It has to. To me, virtual reality is only a part of a bigger ecosystem that’s developing. The technology, the headsets—that’s not that important. People have this ongoing discussion about, “Oh, it’s going to be AR [augmented reality], not VR,” or, “It’s going to be VR and not AR,” or, “No, it’s going to be MR,” or whatever… some other bullshit acronym.

But it’s not that. It’s the fact that we’re creating a new virtual space in which to exist—a total virtual ecosystem. This is where people are going to do their shopping, they’re going to do their social hangouts, they’re going to conduct their business. So for me, the important thing is that DiMoDA is establishing itself as a space within this new virtual world, or whatever you want to call it. The new metaverse, or the new cyberspace—I’m sure they will come up with a name for it soon.

Vicki Dang for DiMoDA 3.0

As we move into this cyberfuture, how do you plan to keep DiMoDA sustained financially—especially when there’s no real precedent for sustaining a digital museum?

This question hits on the frontier of the frontier for us. Coming up with a concept for a sustainable business model is one thing, but penetrating the market and making it so that we can generate money is definitely a whole other animal.

Like you said, it’s because there’s no real precedent. Back in the ’90s, there were web pages that were galleries, so this idea of art in a virtual space is not new. But, to the level that the concept has been evolved with DiMoDA—especially in terms of the way it’s becoming institutionalized—that doesn’t have any real precedent.

The question is, what parts of the classic museum infrastructure do we adapt, and which parts do we write from scratch? That’s the place where we’re doing all the digging right now. It’s hard, because I’m an artist first, and a businessman, like, sixth. But I’m learning how to navigate this world. We’re partnering with folks who are helping us flesh things out, and we’re figuring it out as we go.

There’s a lot to consider—like should we become a nonprofit or a for-profit, and what are the things that we can actually sell? Recently, we’ve been selling these collector-edition items, as a way to fundraise for DiMoDA. But we’re also considering other options, like can we be sustained on grants? Can we be sustained on a board of trustees who provides a yearly operating budget?

At this point, we’re looking at all these alternatives, and also thinking a lot about where we might have leeway to do things differently. Like, can we be a crowdfunded museum? Can we exist within the crypto world or something? What other ways could we make this work? I don’t have a straight answer or a straight formula yet, but we’re definitely working hard to discover that.

If you could go back about five years in time and give yourself one piece of advice, what would it would be?

First, I would tell myself to buy a shitload of Bitcoin. [laughs]

But really—even though sometimes I think maybe I’d be better off if I had learned how to create these types of financial or organizational structures earlier, I actually feel like I’m learning the right things at the right time. Like, if I had started DiMoDA with a business strategy in mind, it would not have had the same spirit that it does now. You know what I mean?

So maybe you don’t need to go back in time and give yourself advice, other than to buy Bitcoin.

You know, yeah. Sometimes your fuck-ups are what make you, and your work, stronger. Honestly, if I could give myself some advice at a younger age, it would have been, “Stop drinking and start meditating sooner.” That would have been good advice for young Alfredo.

Editor's note:

On May 17, 2018, Alfredo will be hosting a pre-release preview of DiMoDA 3.0 in Williamsburg,

Brooklyn as part of TCI's event series with National Sawdust. Learn more here.

- Enter The Void by Gaspar Noé (film)

- Snow Crash by Neil Stephenson (book)

- Maria Sabina’s Wikipedia page (wiki)

- Going vegan (life)

- Black Mirror, all seasons (TV)

- Bonus Round: gardening/farming (life)

- Name

- Alfredo Salazar-Caro

- Vocation

- Visual artist, curator, creative director

Some Things

Pagination