On subverting trauma

Prelude

Working at the intersection of drawing, sculpture, video, and performance, Asif Mian’s practice explores the roles that ritual, masculinity, power, and violence have in society. His varied methods have employed the splicing of rugs together as “event sculptures,” intimidation rituals for performance, and the use of thermal (IR) cameras for video installations.

Conversation

On subverting trauma

Visual artist Asif Mian on creating work as a way to make sense of his father’s death, using art to fill in the gaps of your own memory, and making things that feel vital and important.

As told to Daniel Sharp, 2555 words.

Tags: Art, Inspiration, Mental health, Creative anxiety, Process.

Let’s walk through some of the work you’re making for “RAF.”

Okay. So, RAF is an ambidextrous name. It can be Rafael or Rafiq. It’s a Hispanic name, or a Middle Eastern Muslim name. When I was 20, my father was killed by someone in Texas. Growing up with him, he was in and out of the family, and was quite hyper-masculine, aggressive, and violent. I was in the middle of college when he died. It kind of changed everything, obviously. So, it took a while to make work about him. I’ve been making work my whole life. But the most important thing was my father getting murdered. So it was like, how do I digest this?

About two or three years ago, I recognized this was going to be a big body of work I had to do. I had some information from my mom, so I went back and contacted the county sheriff and started collecting police reports. They only released certain things to me. Meaning, like, the person who killed him is unknown. He’s just a description: he had a red plaid shirt, he’s around five-nine. They were saying he had dark skin, he could be Hispanic, he could be South Asian. I actually had a drug dealer named RAF, but his name could have been Rafael, Rafiq. And then that’s what I gave this ghost of a person. His name is RAF. There are the nonfiction details, and then there’s always a bit of me that fill in the fiction. And that became the structure of this whole project.

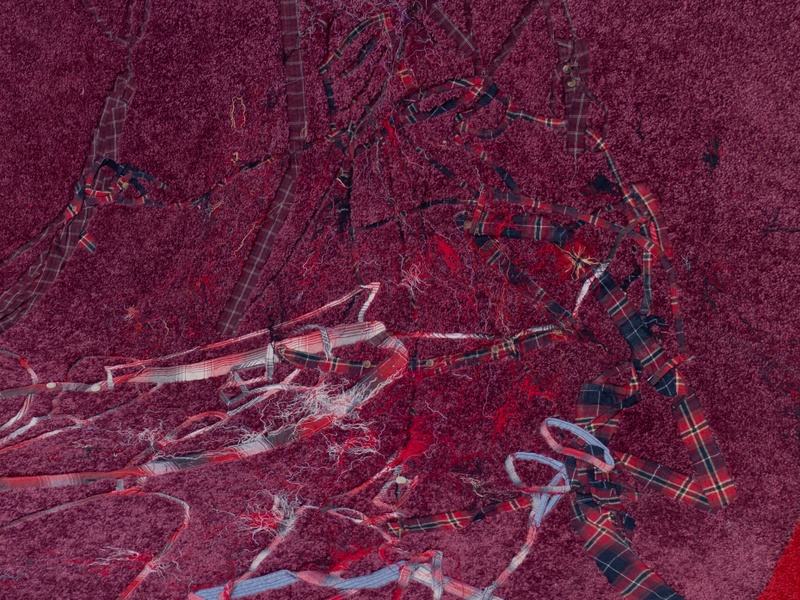

It was a big relief—and an entry point—when I realized that I’ll never know what type of red plaid he wore. So that meant the whole variability of anything I could use was all mine. So, if you Google red plaid, you’ll get a thousand versions of red plaid. Because I’ll never know what red plaid he wore, I’m using all types of red plaid. I’m getting deeper and deeper into something I didn’t even choose. Like, this whole situation, I didn’t choose. It happened. I didn’t choose red plaid. But I’m now taking it on as this basic visual element for the whole body of work.

What did you do with these police reports?

I retraced the detective’s handwriting, in a thicker marker, where it was redacted. Each detective has a different handwriting, and I’m getting so close to the actual handwriting that it becomes obscured. The police redacted information from me, so I wanted to redact some of their information. I did it by rewriting their handwriting.

And are you building stories to replace what’s been redacted? Or are you trying to replicate it, or fill it back in?

It’s always filling in—taking the information that’s there, and filling it in, or extrapolating on it. And that’s part of the therapy of it. All of this has an element of therapy for me. And dealing with the fact that I’ll never find out who RAF is. Originally, I thought maybe one day, miraculously, this whole project would get me closer to who it is. But that’s not the point anymore. It’s not a straight line to who did it. It’s actually a circular line around who could have done it, and what type of person that is. It’s always observing and filling in the gaps. I’m working with this material to understand it better.

And the photos—

Yeah, so these are the photos, where it happened. My mom took them. They have no significance until you connect it. She took them from a car, which is the same perspective every witness had. So it’s her perspective, on the I-20 Highway in Dallas. Once you connect the dots, you know, you start to fill in what could have happened. That’s what I’ve been doing for 15 plus years now.

Essentially filling in a story that you, in some way, could never fill in.

I could never fill it in. I was never there. I just have this insane personal connection to it. Whereas we hear about these stories every day. And we also see them in movies all the time. We’re always fascinated with how they find out. But it never deals with it in the personal, scientific, and emotional way that I think we can do with art.

You mentioned that this is therapeutic to you. I’m also wondering if this ever feels too close to home, or if fear comes into it. What are some of the emotions you feel when you’re digging into this stuff?

A lot. And it changed a lot over the years. In the beginning, it was taboo to even talk about it. I didn’t even tell people for a long time. Because you say it and it’s very heavy, right? And then after a while, I just couldn’t get away from it. I would recreate the scenario, almost every day. I’d think about this location, every day. I always did that as a kid, too. If I met you, I would think about where you lived. I would think about the inside of your house, without ever being there. I would connect geography and architecture to a person. Same thing with this. I had photos, I knew what it looked like, but I would imagine this whole event, you know? We all know what it’s like to go by a house or some place and have a memory attached to it.

What keeps popping up in my head, too, is exposure theory, or bringing a fear up close in order to become more comfortable with it. Some of this work feels like that.

Yeah. It took years of not talking about it, or of not being able to talk about it, to get to now, where I openly talk about it. I think we need to talk about these things. I’m not saying I’m solving anything. I’m just talking about it at such a deep level. It creates a space for therapy. And that’s really what it’s doing. It was like pulling off a band-aid, exposing it. And now, I can use something that doesn’t exist, but the remnants of him does. It’s quite gratifying to do whatever you want with the remnants.

One thing you mentioned before was how the theory of hauntology plays into this work. Can you describe what hauntology is, and how it applies to the work you’re making?

So I was reading all about Mark Fisher, and Ghosts of My Life, where he describes hauntology, a Jacques Derrida term. It’s a play on ontology. It’s a simple idea, where the remnants of other things point to past things around us. For example, I’m looking at this boot. And the dirt on it is a literal remnant of Maine, which is where I was, back in Skowhegan. The dirt on the boot is a remnant of a place. It’s triggering a memory.

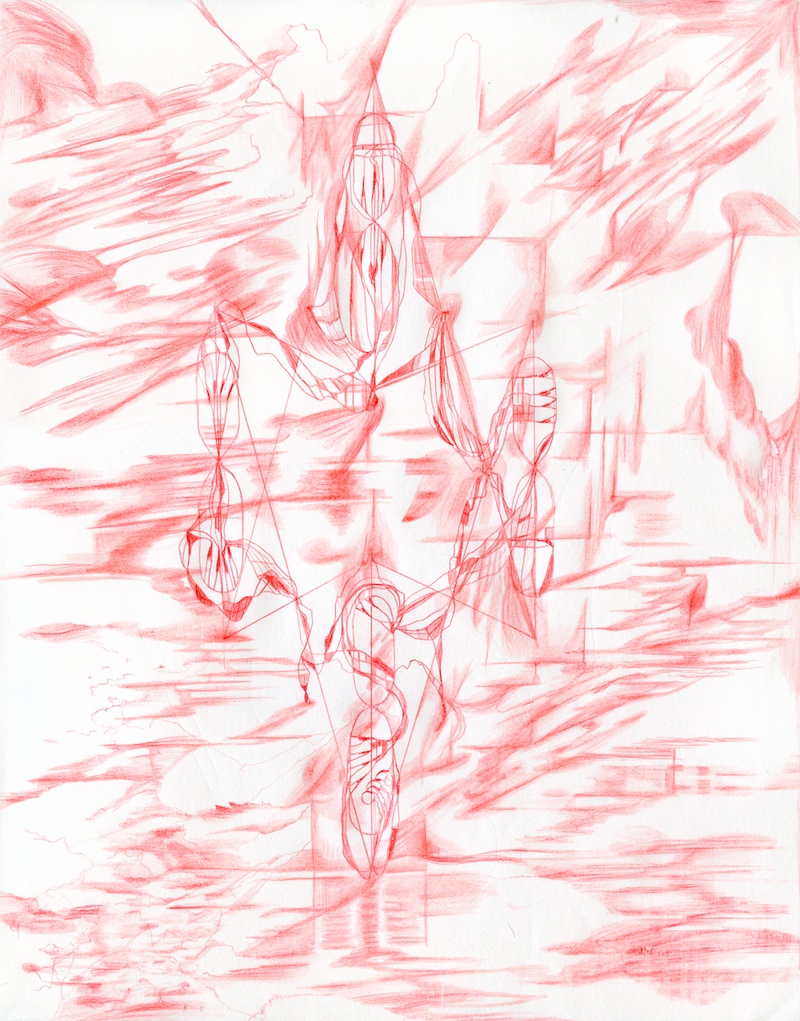

But then this fall, I started drawing the description of RAF’s hair, which was said to be shoulder-length, dark hair. So I just imagined different hairstyles RAF could have, but when you think about hair, it’s kind of an empty volume. It takes up space, but it’s very porous. It’s also used a lot in DNA and forensics. So I made a portrait of his hair. I studied genetics and forensics and social behavior in undergrad. With forensics, all you need is one piece of hair to derive the DNA. Then there’s genetic recombination. When two chromosomes overlap, they swap material and pull apart. This happens all the time. But it’s also kind of violent. It’s this unraveling, exchange, and pulling apart. When chromosomes creates an X, it’s called a chiasma. And I relate that to even our personal and public space. That sort of exchange can be sexual, or intimate, or even violent. This sort of exchange of bodily material or information, that’s a sort of crossover, that chiasma. But it happens down at a genetic level. All the way down, literally to the threads of DNA.

You’re using the actual tools and theories of genetics and forensics and mapping it to your own history.

Yes. Even this phrase we have, “He’s a bad seed,” or “She’s a bad seed,” or a “bad bloodline”—what is that? That’s literally saying something’s wrong with your genetic line, or there’s a trait within you that’s off. But that’s carried on. The gene is the literal remnant of past generations. So your genealogy, skin color, hair, all that, your disposition, or even how you speak or how you walk, has a remnant of maybe someone from generations ago. It’s like the haunting of a gene.

And with red plaid, it’s everywhere in American culture. It’s gang colors. It’s lumberjacks. It’s Wall Street, late ’90s grunge, and drum and bass. And its history, being Tartan and Irish, involved creating your own plaid pattern. You can register your own plaid. Because that is familial. It’s family. It’s heritage.

In these drawings, what appears are these little claws. Claws haunt a lot. They’re in Mughal Ragamala miniature paintings. Stories were told in these panels, like this fight scene, a beheading. And there’s Kali, the monster in Hindu religion, the alien monster, always having claws. Even in our American culture, Halloween, you know. The alien claw.

Around this time, when this all happened to me, in the late ’90s, I became obsessed with Jungle music. It is really fascinating—why are people are drawn to Jungle music? Coming out of East London, it was all about tabla drumming, which is very fast. That is what I grew up with. Punjabi music, and classical Indian music and tabla drumming. That is some of the first music I heard. With drum and bass that was sped up synthetically, to do a drumming that a human couldn’t do. You know, 140-plus BPM. So, in a club, in a place, you heard this really fast beat drumming, that sounded human but was hyper nonhuman. So what he’s saying is, that was a remnant, that was the hauntology of tabla drumming, of human drumming, or African drumming too—but sped up to a nonhuman, synthetic level.

This work is all so personal.

I think about other artists whose work I’ve always connected with, like Kara Walker, or David Hammons. They’re talking about something that’s deeply personal, like race, social politics, and the structure of the economy. Race comes into my work, for sure. But I am very cognizant that my body is also a political body in the U.S.—the brown, Muslim body. Obviously, I have personal ideas about race and growing up Muslim in New York and New Jersey, post 9/11. There’s a lot there. However, there’s also a lot I’ve gone through where no one knew where Pakistan was, at all. They didn’t even know what a Muslim was. You were never allowed to be socially part of the fabric here. You just automatically became this political target. Because of belief and body and color.

But something else happened that superseded everything else for me, right? My father was violent. It wasn’t a peaceful house. Violence was actually the thing to deal with, from the start, aside from race. And from ages 16 and 20, I was a wrestling captain. For a young male, it’s a very important time. It’s a very pivotal time. I probably wrestled to deal with my anger. I knew I had to keep busy. And my father died when I was 20. So this project, RAF, is my way of dealing with violence, directly.

I actually didn’t make art for years. I had been showing some work, but I thought, “This is not really what is important.” And I stopped showing work because it wasn’t about engaging with violence. I stepped away because I just felt like I had to use the art space to talk about something else, something more important. And if I wasn’t, then I shouldn’t be showing.

But you have to change that mentality. Death shouldn’t just be thrown away. Actually keeping the memory of my father alive and remembering what happened is important. It’s not easy. Psychologically, it was quite difficult for a while. I’ve been meditating every day for seven years and that has changed everything. I always start performative works with meditation. I have even done whole drawings while starting out with meditation or in a meditative state. It takes me out of a conscious state. And that’s one way of working with this material, where I’m really observing it. Not in an emotive way, but in a very kind of—I don’t want to say analytical—but in a spiritual way.

Are there moments that you have to take a step back? Because it gets too intense?

You know, not in a long while. I don’t step away from it because it’s becoming too much. If you think about an art practice, it’s not something you repeat every day. And I’m not a detective. But in a way, I’m using art to deduce, to go deeper. Even if it’s just like messing with plaid patterns. I feel like it’s useful.

I’m also curious as to whether the work feels emotionally draining or emotionally gratifying.

It’s not draining actually. It’s totally gratifying, it’s totally energizing. I think that choosing to do this, choosing to put my work out there, helps. There are people who would avoid this. Like me, originally. That was draining. That decision. But once I started, then the plaid unraveled. And it created a new plaid. You know what I’m saying?

I engaged with art in different ways before, and sometimes it was not gratifying. Now I see work everywhere. It becomes an obsession. And I think art can be a good obsession.

I grew up on two types of rugs. Prayer rugs, you could call them Afghan rugs, from Pakistan, which are finely woven. We would literally have those on top of the wall-to-wall carpeting in the house. The prayer rug was the most valuable thing in the house. You’d pray on it, but if you didn’t pray on it, it was not used. It was rolled and put away. The rug was where you met and ate and sat on the ground. But in America, wall-to-wall carpeting is like, just something you step on, right?

Heritage rugs, Afghan rugs, they tell stories. They describe the geography, the land, the animals. They have characters, they have myths in them. That’s storytelling. Here, I’m telling the RAF story.

Asif Mian Recommends

Mark Fisher’s Ghost of My Life

Adrian Raine’s The Anatomy of Violence

UK APACHE’s “Original Nuttah”

Original from 1994

More recently, in a mosque as an Imam

Kelman Duran’s “Moon Cycle II” and this interview

- Name

- Asif Mian

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination