On writing your own history

Prelude

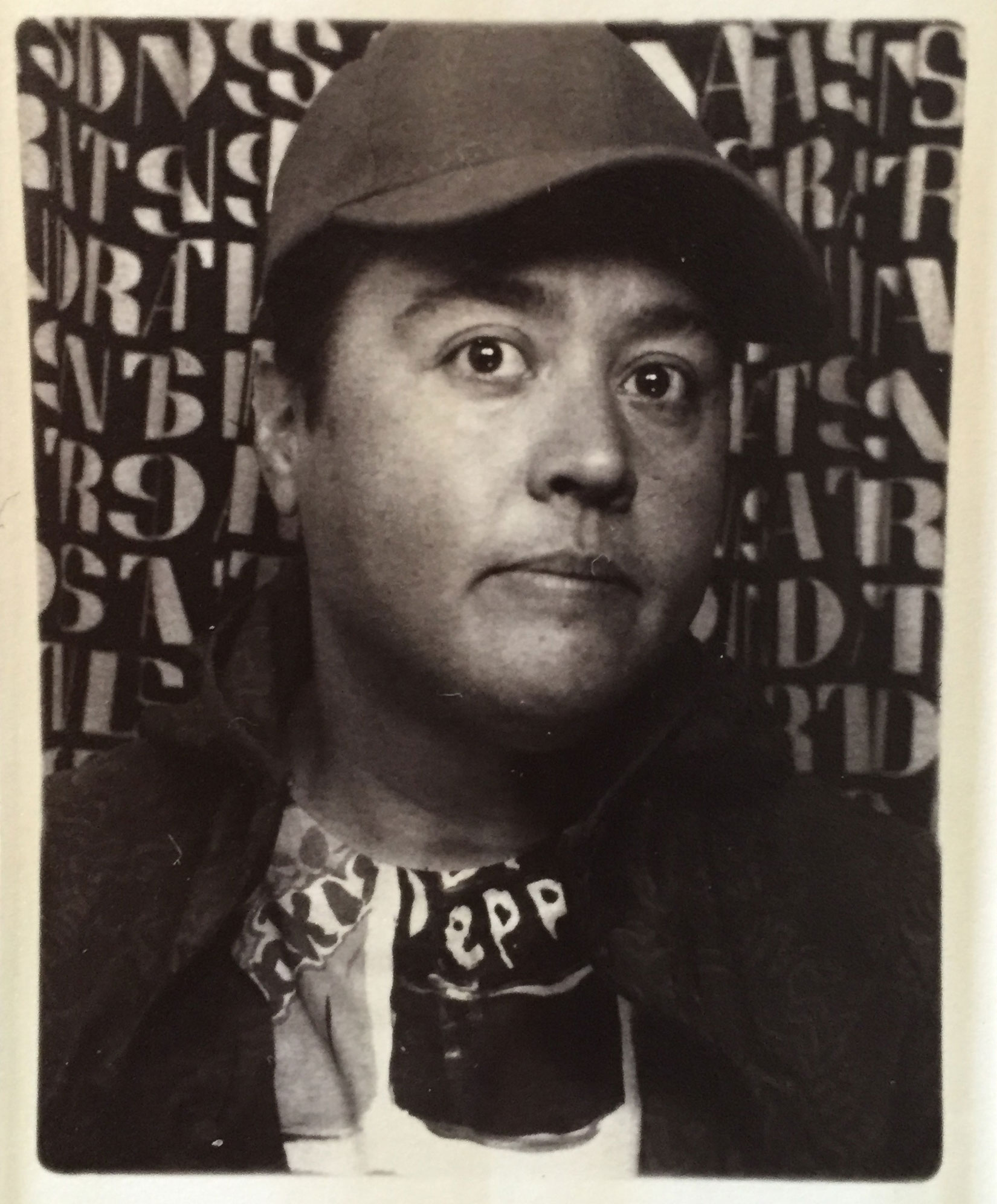

Chris E. Vargas is a video-maker and interdisciplinary artist originally from Los Angeles and currently based in Bellingham, WA. He is the executive director of the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art (MOTHA), a conceptual arts and hirstory institution that highlights trans art’s contributions to the cultural and political landscape. Iterations of MOTHA have been presented at the Henry Art Gallery, Seattle (2016); Hammer Museum, Los Angeles (2014); and Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2013). His current show, “MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project” opened in September 2018 at the New Museum. For this show, which seeks to expand how the complex history of the Stonewall Riots is memorialized, and to acknowledge the ways it has been manipulated, Vargas has invited an intergenerational group of artists to propose new monuments to the riots.

Conversation

On writing your own history

Visual artist Chris E. Vargas on the subjective nature of history, the importance of examining one's own lineage, and what it means to work with institutions—both real and imagined.

As told to T. Cole Rachel, 2686 words.

Tags: Art, Beginnings, Focus, Politics, Collaboration.

So much of your work is about history—both real and imagined, documented and undocumented. Where did this fascination with history come from?

It feels like it’s always sort of been there. I’ve always been interested in various kinds of histories, like activist histories and biographies of radical activists. But all of a sudden I realized that I was immersed in a community of other queer and trans artists who were interested in history as well. Obviously we were gravitating to each other because of the similarities in our interests and in our work. I became very interested in cultural histories, particularly with trans people wanting to understand and historicize our experience, or at least understand it in a context that was greater than just our own lifetime. That is the mission of so many queer people—trying to create and define our own lineage and ancestry.

I grew up on a farm in the pre-internet era, so my notion of gay history was fractured and bizarre. It was something I had kind of pieced together from whatever fragments of gay culture I had access to, which was pretty limited. It’s kind of incredible that right now this kind of work seems to be happening and expanding at such a rapid pace.

There are certainly lots of archival practices as it relates to art, as it’s a thread that people have been following for a while. But as it relates to queer archives and the politics of institutions related to queer identity and experiences, it’s still forming. It’s a very exciting time for queer history. I was born in 1978 and grew up in Los Angeles, which means I also had that pre-internet experience. Our historical understanding was so different then.

MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

You created the Museum of Transgender Hirstory & Art, which is a conceptual institution that people talk about as if it were not. It blurs the line between being a historical institution and a conceptual art practice. How do you explain it to people?

It depends who I’m talking to. You know, sometimes I like to play with the trickery of it all. And I like that people misunderstand it as being an actual institution. That’s sort of how I started it, though. I started the project, thinking it would exist in name only. I would have a name, a logo, and some promotional materials for this museum that was forever gonna be coming soon. Then I realized I could do a lot more with it. I could actually be organizing things as an institution, but without any kind of institutional structure or established brick-and-mortar building.

So I think of it as a conceptual art project with occasional physical iterations. But, a lot of people don’t engage with it as a conceptual art project. People engage with it in a lot of different ways, and a lot of them are really straightforward because people are hungry for a kind of queer history. People want this to be a real institution. I’m not necessarily interested in doing a really straightforward queer and trans history. I’m interested in a critical history. I’m interested in events and people and history, more generally, but I want to use the project to ask people to engage with actual history and institutions in a critical way. I guess I do that to varying degrees of success.

It is interesting to see how many things are written about the museum that would mention, “It does not yet have a physical space,” as if this were an institution that was looking for a space to exist within.

People want it to be an actual place. And I really don’t want it to be. I’m happy if somebody else does it, but that’s not the mission for me. I knew right away that if I was going to actually create a physical space—and I still run into these problems regardless—but if I were to create a physical space I would have to start really defining boundaries. I’d be defining borders of what’s in and what’s out, or what constitutes trans and what doesn’t. Without a physical space, and by doing it as occasional iterations, exhibitions, events, or performances, I get to be a little looser. But that’s not to say I don’t still run into those problems.

People expect me to define what trans is, and I don’t think it’s easy to do that. I know that gender transgressions have existed over time as long as there have been gender conventions, but I don’t want to say what is or isn’t part of this history. That’s an important place for me to work from.

MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

The historical record can differ wildly depending on who is telling the story and what the context is. I think that is what makes the Stonewall Riots such perfect subject matter. It’s a totemic moment in queer culture, but there are a lot of radically different accounts of what happened there and just as many different interpretations of what Stonewall actually means for our culture.

Yeah. It’s exactly what you just mentioned in terms of being a subjective history. That’s why I was interested in Stonewall in particular, because when you go into texts and different people’s accounts of it, there are so many differing versions of what happened that night. All these years later, there are so many differing ways that people tell the story of Stonewall.

I also think a lot about how during the frenzy of the marriage rights movement, how people would try to make a direct line between Stonewall and getting marriage rights, which totally erased all the varying conflicting politics of the people involved. The more radical and the the more assimilationist politics of the movement had a lot of friction with one another. The way that history is narrated changes over time, especially as it relates to Stonewall over the decades. It really points out the way that history is always being told and retold, or written and rewritten, to serve current political ends.

That’s the importance of it and its subjective history with LGBTQ people. It becomes this moment that is trying to be cemented in history in some ways, like with the national monument designation. The story is in danger of getting solidified, but then at the same time it can’t, because only time will tell how it gets retold.

It’s also interesting to examine the story through the lens of transgender history, that being a community that so often weirdly gets written out of the Stonewall narrative entirely.

Exactly. I feel like we’re in a moment where people are reinserting or reframing history to finally include all the queer people, the trans people, and all the queens involved, all of whom were totally written out in initial accounts or had their stories told in strange and often less than respectful ways.

This is an interesting project in that it also often involves other artists, which means not only are you making things, but you’re working curatorially as well. For the show at the New Museum you ask all of these other artists to create artifacts and monuments to be a part of this imagined historical record.

Yeah, it’s always been a blend of those things—of being a curator but then also inserting myself as an artist. I’m mostly creating the frame of the project and all of these things are going to go inside of it, but it’s hard not to also create things for the exhibitions.

So, yeah, it’s a strange role that I find myself in. I feel really hesitant to take on the role of the curator. This ongoing project, even though it’s critical of institutions, also really relies on institutions in order to exist. I rely on the curators, at the New Museum in this case, to really help me think like a curator, especially as it relates to reaching out to a group of artists to make proposals. It’s not just my vision. I really default in some ways to their expertise and their knowledge of working artists, especially really current artists that I don’t know or haven’t encountered yet. I guess it’s funny to make this frame for a show that then sometimes becomes invisible as it gets installed in a gallery. But I feel okay about that.

Were you surprised by the things the other artists made for the show? Or by their attitudes about Stonewall?

I really had no idea how people were gonna approach this. I had some ideas in my head about really basic things, but people have totally exceeded that. I wanted to go beyond a very important but very easy critique of the sculptures that currently exist near Stonewall—the George Segal sculptures. You know there’ve been some really great intervention on those sculptures, with people pointing out how the queer, trans, and people of color who were involved have been erased from the history, and the very literal symbol of white washing that the sculptures represent. Pointing that out was really, really important, and I hoped people would. But then I wanted people to go beyond just responding to those sculptures, and do something bigger. And they did.

When you are part of a marginalized community, there is often the assumption that somehow you’re speaking on behalf of everybody in your community. There is the fear that your representation isn’t the right representation, or you’re not doing it the right way, or that you’re excluding someone. The internal policing within any specific group or culture can be so intense. Have you run into those issues with this project? Has that been a worry?

I’ve been sort of ready for that. I’ve been anticipating a critique, especially as it relates to this project and representing the history of trans people. Especially as it relates to history and stories that predate the term “transgender,” and people who may have been trans but may have described themselves differently. People have been too kind in some ways. I’ve been ready for the criticism, but it hasn’t really come. I hope that speaks to the way that maybe we are past these high-stakes moments of representation. When there were still so few representations of trans people, that was such a big issue. Now that there are more trans people visible in the culture, it’s easier to see a broader spectrum of the trans experience with varying points of view.

MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

I remember when I did this video about the story of Thomas Beatie, the first pregnant man. I remember all the criticism he got, from all sides. It was from straight people who were just like, “I don’t even understand you! You’re a man, but you wanna be pregnant? I don’t get it.” And then trans people who were like, “How could you confuse people? How could you tell your story in such a complicated way? You are not representative of the larger trans masculine community who would never wanna do this with their body.” There were so few of those high-profile moments of visibility then, so the stakes were so much higher. I hope that we’re past that in some regards. I hope that now there’s a better understanding of the variety of ways that people can live their trans lives that doesn’t overly rely on one person to do all the cultural work.

Given the expansive nature of your work, what does your creative practice tend to look like? Do you work in a studio?

It’s all over the place. I have this fantasy of my life as an artist that has never existed. And I’m always like, “I need to do solo things alone that don’t rely on communicating with a lot of different people, or organizing exhibitions, and doing all the logistics myself.” I would probably never be able to work like that, but I always want to. For some reason, I am just drawn to these complicated, sprawling sorts of projects. There are ways that I imagined how my artist life would look when I was younger, and it just doesn’t look like that. I guess I haven’t accepted that yet.

But regarding this project, because it relies so heavily on exhibiting in institutions and working with archives, it is particularly administratively exhausting. I would love to go back to making videos by myself at some point. I don’t know if I ever will, but I fantasize. I have romanticized that period in my life where it was just me and a tripod with a homemade green screen. I doubt I could actually go back to that, but I think about it. I resist my own inclination to work with people and organize complicated things, even though that’s somehow where I always end up. I fantasize about turning my back on that, but ultimately I don’t think I could ever move away from this way of working.

For young artists who are going out into the world and are doing unconventional work, what do you tell them?

Oh my god, how do you answer this question without being cheesy?

Cheesy is fine. Cheesy is usually the truth.

Even though I just told you that I resist certain inclinations of ways of working, I feel like I’ve never done anything that didn’t really call to me. If you’re really doing work that is honest and true to yourself and not pandering or trying to be trendy, if you’re honest with your work and your interests, then I think people will respond to that. That’s been true for me. I’ve always done stuff regardless of the attention that I was gonna get. I know that it sounds like that is an easy thing today once you’ve already gotten some attention, but it didn’t happen overnight and it wouldn’t have happened at all if I hadn’t been making work that felt honest and truthful.

Also, it’s worth mentioning, that I think I probably said yes to way more things than I should have early on because I thought that that was necessary. And I think that helped. In the beginning you just try and do everything that comes along, but then as more opportunities opened themselves up to me, I was able to be more realistic about what I could do in terms of my time and energy. In the early days saying yes to things that are interesting to you and being as ambitious as you can in that way can really help you, but there’s a point when you have to be totally discerning about what you can take on. It’s hard to define exactly when that moment happens, but you’ll know it when the time comes.

MOTHA and Chris E. Vargas: Consciousness Razing—The Stonewall Re-Memorialization Project, 2018. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson/EPW Studio

Chris E. Vargas recommends:

-

A Tale For The Time Being by Ruth Ozeki

-

Latinos Who Lunch podcast - latinx culture!

-

One From the Vaults podcast - trans history!

-

Kabocha squash with nutritional yeast and sriracha

-

Isolation tank float therapy

-

Hiking

- Name

- Chris E. Vargas

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination