On the value of process and what success actually means

Prelude

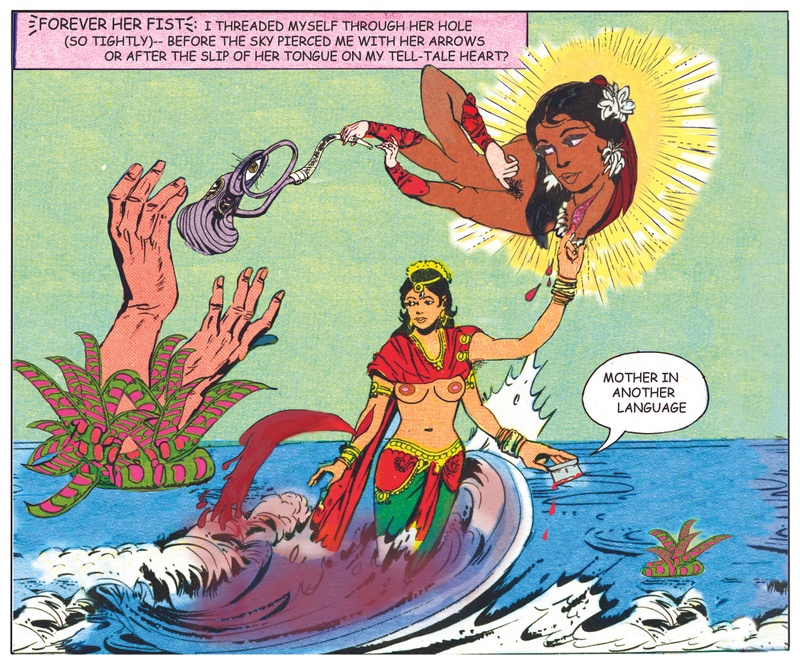

Chitra Ganesh is a Brooklyn-based visual artist whose work encompasses drawing, painting, comics, wall installations, video art, and more. Through studies in literature, semiotics, social theory, science fiction, and historical and mythic texts, Ganesh attempts to reconcile representations of femininity, sexuality, and power absent from the artistic and literary canons. She often draws on Hindu and Buddhist iconography and South Asian forms such as Kalighat and Madhubani, and is currently negotiating her relationship to these images with the rise of right wing fundamentalism in India. Ganesh graduated magna cum laude from Brown University, and received her MFA from Columbia University. Her work has been exhibited widely across the U.S., Europe, and South Asia. Her works are held in prominent public collections such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art, San Jose Museum of Art, Baltimore Museum, the Whitney Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art.

Conversation

On the value of process and what success actually means

Artist Chitra Ganesh on the cultural iconography that informs her work, working across a wide variety of mediums, and what we can learn from being attuned to process—both other people's and our own.

As told to Anupa Mistry, 2618 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Inspiration, Success, Multi-tasking, Identity, Politics.

Your work connects histories of surrealism, mythology, and cultural iconography with contemporary comics and sci-fi aesthetics. What do you recall as your earliest aesthetic interests that connect to the work that you’re making now?

Graffiti on the subway. Painted movie posters I saw when I spent time in India as a kid. I would also say textiles and everyday household bling like glitter and sequins, pom poms, iridescent nail polish. I was also drawn to how everyday objects and icons adorned one another, whether it was how our neighbors decorated their homes and backyards during Christmas, or the roses and textiles that accompanied idols of deities we had at home. With the graffiti and the movie posters specifically, it was as much about the experience of witnessing the work being made on site–seeing artists creating in an urban public place, climbing scaffolds and running in and out of subway tunnels as part of their process. In both cases, I was drawn to the presence of the hand, which at that time was obviously more common. These painted marks made by human hands were like fingerprints of their own to me, and through them you could feel a physical, bodily connection to the work.

At what point did these ideas, or observations really, become a guiding ethos for the work that you’re making now? When did you begin to “intellectualize” these influences?

My own material process helped give things an intellectual framework, thinking through ideas of representation, colonialism, sexuality, and power. The way that I approached collage in my early to mid-20s allowed me to use the process as a way of engaging and coalescing wildly different visual registers, histories, time periods, and modes of representation. With making comics, things tend to come together when I have enough time away and I’m able to look again with fresh eyes. I have new insights or new ways of thinking based on the present and what I am thinking about now and what other representations are out there.

I was rereading those Amar Chitra Katha comics, [a long-running Indian educational comic book series about history, myth, and culture, foregrounding Hinduism], and some of the comics of the Hernandez Brothers, who I love and grew up reading. Love and Rockets is about a Latino working-class neighborhood, or a class-diverse neighborhood, and there are a lot of female characters and a lot of sex. It’s very erotic and bawdy. There are these two characters, Maggie, a mechanic, and Hopey, her friend. They were something in between friends and lovers, and often portrayed as a couple. I was just thinking about that and the place that those stories had in 1991, when there were not that many other representations out there. You know? Looking at things like skin color and the portrayal of women and how that had larger significations that I didn’t understand until I looked back on it with adult eyes.

You draw, paint, and also work with animation, video, and installation. Are there any drawbacks to having a practice that’s so varied?

Even though the practice appears varied in that way of producing works across a broad range of media, there are some core threads and interests that run through it all. For example, an interest in the presence of the hand and in figuration, and how bodies that are gendered or mis/read as female often serve as the site where material violence and social conflict get played out. I’m also thinking about the shape-shifting possibilities of myth, the physical and psychic limits of the body, the idea of circular or non-teleological time, and new ways of embodying desire. The way you would talk about time in painting or poetry would be different than in animation, although all three are excellent media through which to think about the passage of time.

And is there a process of kind of familiarizing yourself or acquainting yourself with a different medium before you make work in it?

Oh, yeah. Printmaking is something that I did for the first time in fifth grade, and I’m very familiar with linoleum carving and cutting and ideas of positive and negative space. But with something like animation, I came to the process through familiarizing myself with it over time, slowly augmented by doing things like taking classes, watching a lot of animation with an eye to understanding how different techniques and formal strategies work, and spending as much time as I can with other material and the media that I enjoy. I also work with others to produce the work in the media I have less familiarity with. The contemporary art world might still extend aspects of the myth of artistic genius by exalting select voices and a star system, but all large-scale art projects and exhibitions are, in reality, borne through collaboration.

How do you start a new project?

I don’t know. How do you start a project?

It’s hard. Sometimes it’s like I come across something that allows me to make real an idea that I’ve been thinking about.

Mm-hmm. And don’t you feel like there’s always some kind of seed, but the seed is different every time? The seed for me, for example, could be a conversation I had, a textile pattern or sci-fi movie poster I saw, or a news story I’ve been following for months. There’s also the question of how a project can both express and evolve ideas that tend to be an organic outgrowth of my interests at that time. Sometimes the projects I start remain behind the scenes for quite a while, years even, whereas others are realized on a more compressed timeline.

And how do you know when a project is done? I feel like this is hard for people.

Sometimes it’s about time. When the completion is dictated by some kind of deadline-based condition, then I feel like I know it’s done when there’s the right balance of things in the work. Sometimes that means having to remove a chapter or a figure or a whole set of ideas from the work because there wasn’t enough time and space for all of those things to be treated with equal sensitivity and care, or because keeping every element in the mix would obfuscate or dilute what was at the core of the work. To help me arrive at a state of “doneness” or resolution, I do have a few people that I trust and share my work with. You have to be able to take criticism, ideally from comrades and colleagues whose values are aligned with yours. It’s not just about what it looks like, but trying to understand how a project can help me evolve larger guiding principles.

ASMR was part of the inspiration for your series Chitra Ganesh: Her Garden, a Mirror. In another interview you were speaking about your references and included an amazing South Indian DIY cooking video called “Watermelon Chicken By My Granny” as an example of skills-sharing and amplifying unheard voices. How do you think about voicing the unheard via ASMR?

The idea of voicing the unheard wasn’t what motivated the ASMR project. I was moved by a desire to trace and locate the impulses towards collective skill sharing and knowledge transfer that animate Sultana’s Dream, a work of Bengali feminist science fiction from 1905, around which the Her Garden, a mirror exhibition evolved. I wanted to focus on the idea of collective skill sharing and knowledge transfer by and for women, queer, and trans folks through channels located outside of traditional pedagogical or governmental contexts. Like people teaching each other how to compost when there’s no infrastructure for garbage pickup, or teaching older women how to ride motorcycles so that they feel more autonomous and less dependent. There are also a lot of hierarchies of food and assumptions around sustaining ourselves that we can see differently through ASMR videos.

When you actually watch someone in process, you’re engaging in kinesthetic learning and knowledge is being transferred through the body. The most important thing you should be able to have now, as an artist, is the ability to find the knowledge—not the knowledge itself. Because the technologies keep changing, you know? Knowledge isn’t stable. So what’s more important? It’s about how to find process, and keep learning process, and being open to keep learning process.

Do you think it’s hard for people to be open to process?

No. I think it’s difficult to know how to engage process when everything in our capitalist product-oriented world seeks to conceal the processes and labor behind innovation and beauty. But I think people love process. I mean, there’s process porn. There’s food videos. There’s people painting their toes. There’s entire communities and conversations that are generated in the space-time vortex of braiding hair. Process is refreshing because it has the possibility to interrupt, by pointing to a slowed down accumulation of looking and engagement. Sounds, smells, or quality of air that one associates with certain processes, specifically related to food or touch, linger on a much deeper affective and psychic level.

There’s also a sense of concealment that is encouraged in order to emerge fully-formed or create something fully-formed, which does encourage a kind of veiling. Those contrasting impulses are actually really interesting.

Yeah, and not just concealment for our artwork, but for every commodity we buy. Everything is very presentational. And I think the presentational part of say, food, is fun and important, but it’s not everything. It’s just plating. And also with the granny making the watermelon chicken video, I just feel like when you get really specific like that, another piece of work that it does is upending a lot of stereotypes held within the west and pockets of the diaspora. With that video specifically: that Indian food is Punjabi food, that Indians are vegetarians, that South Indians are vegetarians, that Tamils are Brahmins. Just by watching that one video you see nothing is true, you know? That’s also something that drew me to ASMR videos.

Do you have any thoughts on what young people are broadly referring to as “diaspora art” these days?

In the United States right now, all political discourse, including racial discourse, has a tendency to be flattened and presented in very polarized or binary terms. There has been a long history of Asian invisibility and a disregard towards anti-Asian violence that makes itself apparent in the demographics and representational trends within contemporary art as well. The last 20 years of race in America has been thoroughly underwritten by Islamophobia, and there is barely any Muslim representation within contemporary art as well. Questions around Indigeneity, Palestine, and Blackness tend to take a front seat because these are the places where American guilt is immediately located, and has historically been implicated, you know? It’s hard to know how the category of diaspora translates in this particular moment, and my sense is that it would be very different actually in Canada or the UK.

Well, that’s actually why I wanted to ask you about “diaspora art,” because one of my criticisms is the impulse to oversimplify a range of cultural motifs, political contexts, and migration histories as a way of reclaiming personal identity.

Some of this work exists because there have been multiple generations that have come about since, you know? It seems to be work that’s a little bit less specifically tied to the country of origin, and maybe more tied to how some symbols and signifiers have permeated the landscape, albeit retaining a sense of marginality. On the other hand, there is a small corner where I feel greatly comforted to see a deep engagement with history, politics, and aesthetics in South Asia, rather than a self-aggrandizing presentation of individual identity markers, or performances of vulnerability that could be commodified or cannibalized. I am thinking about what the remarkable messaging of @SouthAsia.art or @Brownhistory have shared in response to the lurch toward authoritarianism—developing a citizenship that is exclusionary and anti-Muslim above all, happening in India.

One concern is art that is not in conversation with or unaware of the work that’s come before it, that seems unaware of the generations of queer south Asians in the diaspora that preceded and made space for this contemporary moment. How do we generate a sense of movement in work that touches on these identities, which aren’t static? I think in part by placing them in conversation with one another across generations and seeing what we see. And also by placing them in context with current politics. In my own work, I’ve tried to expand on and move into and away from certain mythological iconographies because I cannot get involved in something that’s being recuperated by Hindutva right now. It won’t be the story forever for all of Hindu iconography. But let’s think about what’s going on with authoritarianism and cultural hegemony in South Asia, and how that looks different with work being made now versus work that was made 40 years ago or before the neo-liberalization of India in the ’80s.

How do you define success?

That’s hard. Over the years, I have had to periodically re-evaluate these markers—they have shifted to accommodate my own autoimmunity and chronic health issues, as well as the structural conditions that continue to shape the trajectories available for women artists in a field that continues to be largely white and male. Now, success means: Being able to devote a majority of your time and headspace to what you do and also maintain an intellectual or artistic space that can be yours or that can be private, or that cannot be co-opted. Being able to have a full life and fall in love and have all kinds of registers of experience that are outside of the career. Being there for the long haul and the slow burn, year after year, and trying to have structures in place including friendship, artist centered non-for-profit spaces, collaboration, teaching and writing.

Chitra Ganesh Recommends:

-

Making time for people and love outside of your work life/structures/world

-

Resisting the worldwide lurch towards global authoritarianism, like the current Indian government’s moves to build a brutal authoritarian and exclusionary citizenship in India. New modes of visuality are being diverted to help fascism take root in in India, via surveillance technologies that profile protestors, stoking a climate of fear and policing dissent.

-

Music in the studio. This song by Ustad Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan will scrape your insides clean if you let it.

-

Long walks around the city, especially my favorite winding walks in Prospect Park, Brooklyn.

-

Reading in bed and on the subway:

Marlon James, Black Leopard Red Wolf

Ocean Vuong, On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous

Charles C. Mann, 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus

Imani Perry, Looking For Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry

Nayanika Mookherjee, The Spectral Wound: Sexual Violence, Public Memories, and the Bangladesh War of 1971

Marjorie Liu & Sana Takeda, Monstress

- Name

- Chitra Ganesh

- Vocation

- Visual Artist

Some Things

Pagination