On thinking about your creative process like detective work

Prelude

Visual artist Mariana Castillo Deball uses installation, sculpture, photography, and drawing to explore the role objects play in our understanding of identity and history. Engaging in prolonged periods of research and field work, she takes on the role of the explorer or the archaeologist, compiling found materials in a way that reveals new connections and meanings. She recently had her first museum show in New York, Mariana Castillo Deball: Finding Oneself Outside, at the New Museum. The show brought together a newly commissioned work and recent works never before seen in the US.

Conversation

On thinking about your creative process like detective work

Visual artist Mariana Castillo Deball on how deep research can feel like detective work, the benefits of being both an artist and a teacher, and why making a living solely from your artwork shouldn’t always be the goal.

As told to T. Cole Rachel, 2108 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Mentorship, Education, Collaboration, Inspiration.

Are you the kind of artist who can work anywhere, or are you happier being in your own studio?

No, I’m quite rooted. I’m usually working in my studio in Berlin. I also produce things in Mexico, but here it’s mostly easier to work with different people or to do research.

What are your ideal conditions for making new work?

I have different moments of production. So I do work in my studio on a regular basis, which is also like a kind of bureaucratic part of my work. The studio is where I need to answer emails and do all the logistics, but it’s also where I do all the material tests and create sculptural works. It’s also the place where I do drawings, because I do a lot of drawings, as they’re sketches of the things I’m producing. The other part of my work, especially if I’m working on a specific project, often involves needing to travel or talk with different people, and to visit different archives.

So there is a big part which is related to people I collaborate with and the people I am in dialogue with. I depend on the expertise of other people when I need to learn how do certain things related to my work—things like, how to make a garden or how to use certain materials. I embed myself into this dialog and this also becomes a very important part of my work. I also teach at a university in Germany and I consider that a part of my practice—the teaching job. The dialog I have with the students, all the things we do together—it’s something that became very important in the last few years.

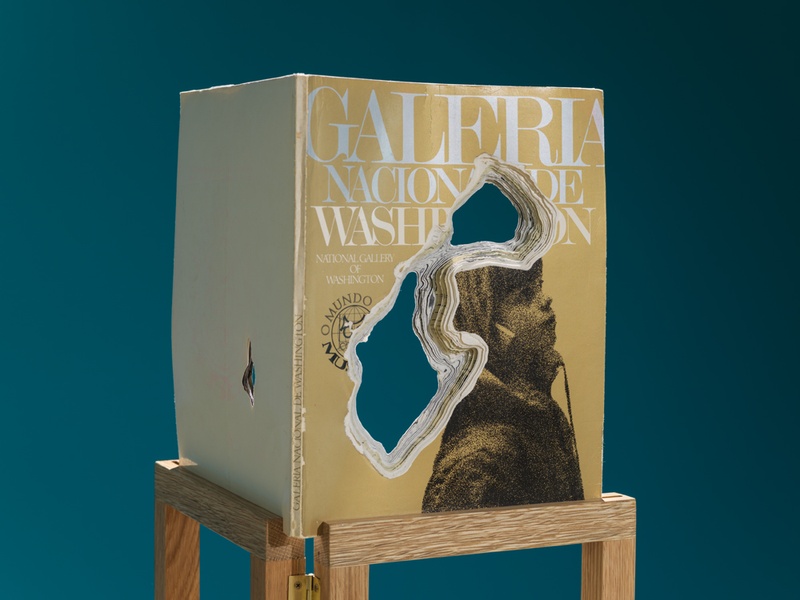

Mariana Castillo Deball: Finding Oneself Outside, 2019. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

I’ve talked to so many different artists about teaching and about the role it plays in their life and work. For some people it is a means to an end, a way to make money, to have health insurance, etc. But it is also interesting how many artists say that teaching is a necessary part of their practice.

Totally. As an artist you often need to deal with traveling, and doing things related to making work or doing exhibitions. Sometimes the dialogue you have with colleagues is not as strong as the dialogue you have when you are still studying. Those are the kinds of conversations I have with my students. They ask you these very fundamental things—Why am I an artist? How am I going to live?

These are questions that, if you are a teaching artist, you can easily kind of forget about because you start to think of yourself as already being in this certain kind of position. You can forget about all that it takes to actually do this, all the different things you need to learn in order to be an artist. Teaching reminds you that there’s not just one way, but many different ways of doing it. It constantly expands your thinking.

When we ask artists what they need in order to do their work, the most common responses are often time, money, and space. Beyond those things, especially when you’re teaching and traveling a lot, how do you strike a balance that works? How do you carve out the time not only to make things, but also just to think?

That’s the most valuable time, those deep-concentration moments. Being able to sit in my studio and make drawings is great, but it’s also the most privileged moment I can have. So much of the time I need to be traveling, going to shows, teaching, and in those moments you are really outside of yourself. You have to always be managing and thinking and planning and finding money—that is part of the work, too.

Mariana Castillo Deball: Finding Oneself Outside, 2019. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

I know people often talk about needing money in order to do their work, but money won’t always solve your problems. It depends on what you’re doing. Sometimes you can do something with nothing, and sometimes you have the chance to have more resources, but I don’t think the economic aspect is the one that’s going to solve the problem.

Money is not a substitute for having good ideas.

No, not at all. Sometimes it’s exactly the opposite.

Given that you do travel a lot, particularly between Berlin and Mexico City, have you learned to adapt your process accordingly? Have you learned to work wherever you are in some capacity?

No, not at all. For example, on airplanes, the only thing I can do is read. I try to read a lot of fiction when I’m on the road. I like it because it creates an imaginary narrative in my mind, so even if I’m jumping from one place to another, I have this book that goes from A to B. The book becomes something that connects all the different places. Also, all the bureaucratic stuff, the emails, etc. All of that takes about 50% of my time.

Artists often talk about that—how you never anticipate how much of the job of being a working artist would involve just doing paperwork and applying for grants. You can’t pretend that part of things isn’t important, unfortunately.

It’s a big part of the work. I have a small studio and I have two people working with me, but only part-time. I enjoy the days when I can just be on my own at the studio. I don’t want to always be talking or telling people what to do. It’s important that I can also just be there alone with myself. I also end up doing a lot of the bureaucratic stuff myself because I don’t always delegate things very well.

Your work employs a wide variety of different methodologies. Do you find that it’s important to sort of rethink your way of working each time you begin a new body of work, or is that something that just kind of happens organically?

I think it goes together with whatever project I’m working on. For instance, when I was at university I was very concentrated on printmaking, so this is something that still appears in my work. Even when I work with sculptures, I’m very obsessed with the matrix and the positive and the negative and how you can reproduce an object and slowly transform it into something else. So I think this is something that is always there—not so much as a technique, but as an approach.

Mariana Castillo Deball: Finding Oneself Outside, 2019. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

And then the other techniques I do, sometimes they come from something that I really liked and then I try to crack the recipe and try to see how they were done. So I’m also very interested in the knowledge that is embedded in specific techniques. I think it’s also very important to try to find in these texts and sources and research how things were done. It’s a knowledge that was often transmitted through practice. So I don’t know exactly how to extract colors from a plant in the same way that people in the 15th Century were doing it, because they didn’t leave a very clear recipe. Maybe they made a drawing and maybe they left a hint, but the only real way to crack it is to repeat it and do it myself. It’s this idea of repetition but through practice. Sometimes I need to repeat these processes in order to understand how this material knowledge actually works.

It’s sort of like detective work.

Exactly. I learned that many years ago. Once I did a print with a friend in the Netherlands and there was one person who was doing something based on scientific instruments. They tried to understand how people built those instruments, but since there is no instruction manual, they just needed to dismantle them and build them again. They also had to imagine things, like, “If we are leaving Norway and we need to find a tree, what kind of tree would we find? And then which kind of tools did we have to cut it?” I thought it was very fascinating that it was like a non-verbal way of learning history.

In your work with students, do you see certain patterns emerge? Moments when they get in their own way, or recurring stumbling blocks? Do you give them advice?

Well, something I try not to do is show them work by other artists who are doing similar work. I don’t want them to fall into a pattern of immediate repetition, even though they can find that stuff on the internet and then just imitate it on their own. The most challenging thing with students is to try to see how they are thinking and how you can advise them to follow that thinking. It’s not through imitating, but through thinking in a certain way. I also want them to think about what kind of artist they want to be. Do they want to be an artist who is just selling work in galleries, or do they want to do social work or institutional work? In the school where I teach, more than half of my students are studying to be art teachers, which is very interesting. I learn a lot from them in thinking about how you teach art in a primary school, or how you would teach art in high school.

Being an artist is becoming so much more difficult now, so I also encourage students to also do other things, to have other jobs, because it’s almost impossible to just exist by doing art. This is something I myself did for many years. It’s only in maybe the last seven years that I have been able to live from my work and from teaching, but getting there takes, I don’t know, maybe 20 years of your life. Living life as an artist is not a bad thing, but I also learned a lot of valuable things from all the other different jobs that I had.

Trying to earn a living through what you make can have a negative impact on your work, often in ways you don’t even realize.

Yeah, and sometimes you don’t understand that until you try and do it. For example, I never produce art for art fairs because the only time I did it I felt completely depressed. I was doing all this work, and then I saw it in the art fair and then I realized that it had nothing to do with what I was really thinking about and that the context was not a context that I wanted the work to exist within. Maybe you can make work for a show and then later these works can go to the market. To make work immediately for the market is not an experience that I enjoy.

If you are only making work for fairs or for commissions, it’s like following a carrot. It does happen sometimes, but I always try and exit those situations or create new spaces for work. I will initiate projects that make no sense or have no budget. I frequently do that with the people I collaborate with. You need to be spontaneous, otherwise you get so bored. I like to take on projects that are very long-term. When I get an invitation like that it makes me happy. I can use that opportunity to think about something for a long time, and to really let my ideas grow.

Mariana Castillo Deball: Finding Oneself Outside, 2019. Exhibition view: New Museum, New York. Photo: Maris Hutchinson / EPW Studio

I’ve read some amazing books lately. I got really into Octavia E. Butler and I’ve read many of her science fiction books, particular her book Kindred. I also recently read a great book by the Mexican writer Valeria Luiselli. Her last novel is called Lost Children Archive, it’s an amazing book. Oh, and another book that I really like is There There, from a Native American writer named Tommy Orange. It’s a beautiful novel. Read those.

- Name

- Mariana Castillo Deball

- Vocation

- Visual artist, teacher

Some Things

Pagination