As told to Miriam Garcia, 2760 words.

Tags: Art, Writing, Process, Beginnings, Education, Production, Collaboration.

On not underestimating your audience

Visual artist and writer Verónica Gerber Bicecci discusses the balance between working with images and text, the power of Venn Diagrams, and the benefits of reading and collectivizing your work.Filmmakers, writers, and other creative people have told me that an obstacle they encountered to define themselves as artists was that they didn’t know how to draw. So they found their artistic practice in other mediums. You’re a visual artist, did you ever question your ability to draw? When did you decide to use text in your work?

I have the impression that I don’t know how to draw either! My drawing is quite simple, basic, elemental. I’ve always known that my drawing skills, in terms of what art academia demanded, were below the expectations. And still, I draw. The same thing happened with writing, I didn’t fulfill the formats that academia or “creative writing” demanded. And still, I write.

Obviously, I have a conflict, both silently and loudly, with formats. It’s difficult for me to understand exactly what genre I practice. And it wasn’t so much that I consciously wanted to get away from the formats, but many times I ended up with a different format from what the professor asked me to do. I wasn’t a great student. But fortunately, my artistic education was very flexible

In your first novel, Empty Set, you used Venn Diagrams and text to tell the story. How did you discover these diagrams and why did you decide to start using them?

I’ve never found an answer that satisfies the question on how the Venn Diagrams appeared in my work. I had a faint memory that the first time I used them was in my Bachelor’s degree thesis; it’s called Espacio Negativo (Negative Space). And I think Venn Diagrams were useful to explain visually what a negative space is. Which is, in a drawing, to look at the holes between things more than the things itself, to draw from observing the void instead of the objects. The idea of the negative space has been essential in my work.

What was the creative process of writing Empty Set? Did you start by making the sets and then decide to write the story, or did you already have the idea and after you had the concept you thought that the best way to tell it was with this mix of the Venn Diagrams and text?

Well, an idea is not something that is clear from the beginning, but something I build up from small pieces and minimal daily decisions. One day I notice that I finished something and I don’t remember very well how I got there. What’s very clear is that writing Empty Set took me a long time. It took me almost four years to finish a book that is quite short. The process was very intuitive as well. I started writing until I reached a point where I felt that I needed to see things from a different perspective, and that’s when the Venn Diagrams started to appear. I took a big notepad and tested many drawings. I obsessively repeated the same micro story of a drawing over and over again. And after the first drawing entered in the story I kept on coming back and forth from the computer to the notepad.

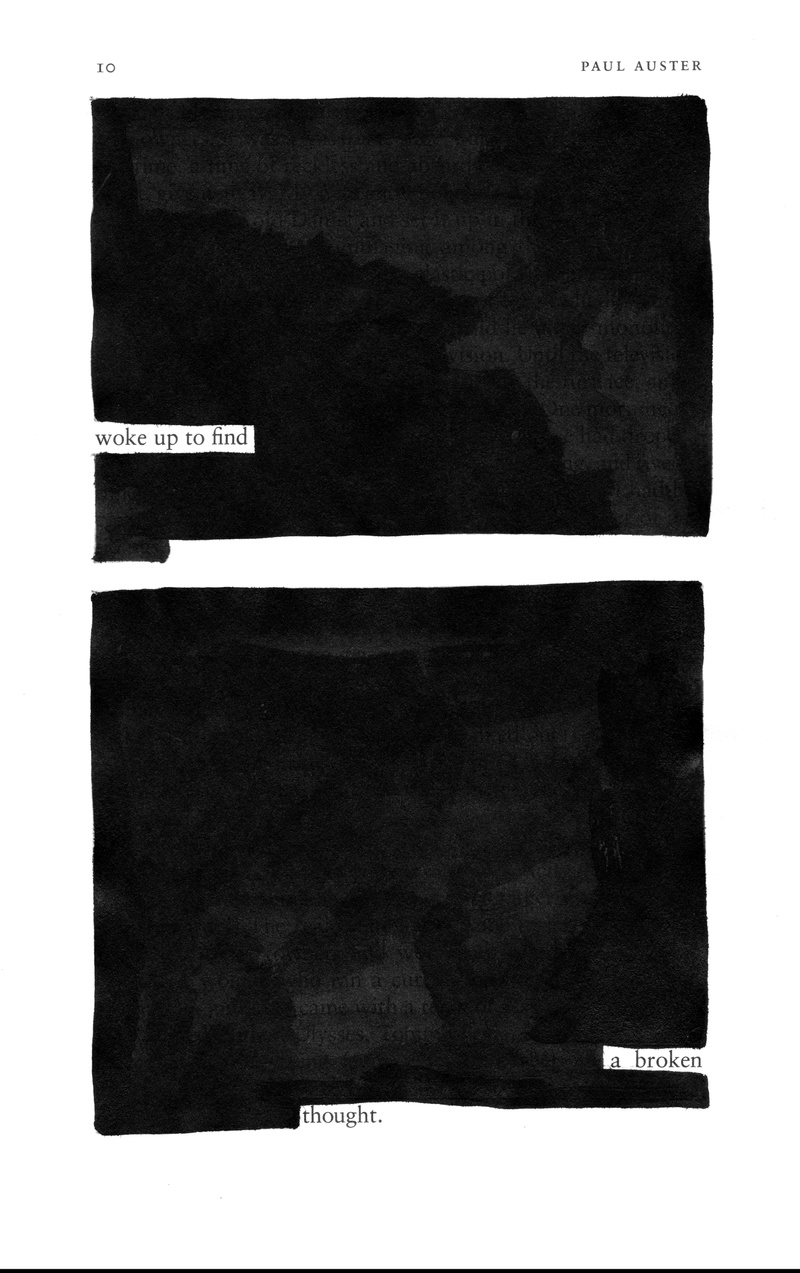

Diagram of Silence #13 (Cartography of Silence, Adrianne Rich) 2018

Did you ever think “maybe this isn’t the right way to tell the story?”

All the time. I enjoy doodling, erasing, and throwing away sentences the most; those moments seem to be profoundly liberating to me. The only risk, of course, is not to find anything that is worth keeping and ending up with nothing. But what has been crucial for me is to share my projects and put them on the collective table: to read out loud and discuss with others, to see and think with others.

Every text or image I do is made with others, that’s the only way for me. I usually meet with a group of friends and we work on each other’s projects. Taller Diagonal (Diagonal Workshop) with Guillermo Espinosa Estrada, Juan Pablo Anaya and Luis Carlos Hurtado has continued for almost 10 years. And recently, Taller Tijeritas (Little Scissors Workshop), which started recently with Yolanda Segura, Mariana Oliver, and Sara Uribe, three writers and friends who I deeply admire.

When you were developing Empty Set, were you thinking of a specific reader? Should a writer think about the potential audience? Or would thinking about this would be a creative obstacle?

What I find most important when I think about the audience or readers is to not underestimate them. The whole art and literature fields seem to insist in underestimating readers in their aim to sell more or sell better. Simultaneously, I believe that we have the responsibility to set up, along with our book or installation, the reading clues that will allow the audience to decipher our personal alphabet. Not only to suggest a story or an idea, but to make an artifact. Of course, I don’t mean to be didactic or to sweeten anything, but to find a coherent way, both conceptually and aesthetically, to make a mechanism, a built-in hint device.

On the other hand, the idea of a writer with no public also interests me, and actually it’s an idea that I’ve been bouncing around after reading a very polemic book that we published in Tumbona Ediciones a few years ago: Left Literature by Damian Tabarovsky. In the book there is a small essay called: “The Writer With No Public.” I must confess that I got upset the first time I read it.But it’s something that we definitely need to discuss.

To quote Tabarovsky: “In the current state of capitalism, we all have had or will have, in some way or another, some type of relationship with the market (and with academia as well, since the circulation between both spaces is so intense).” There is no way, no matter how hard we try, to remove ourselves from that system. So, he argues that a writer with no audience would be capable of writing from outside of language, outside of the market, and outside of academia. The only way to think from outside this atrocious situation is if there is such a thing as a “writer with no audience,” which is a hard idea to carry out but also refreshing.

I’m still thinking how this could be possible. Maybe, as contradictory as it sounds, the writer with no audience will be our only chance, just a brief moment in the history of writing. An exit, but not an escape, from where we will be able to find or invent another way of writing and reading.

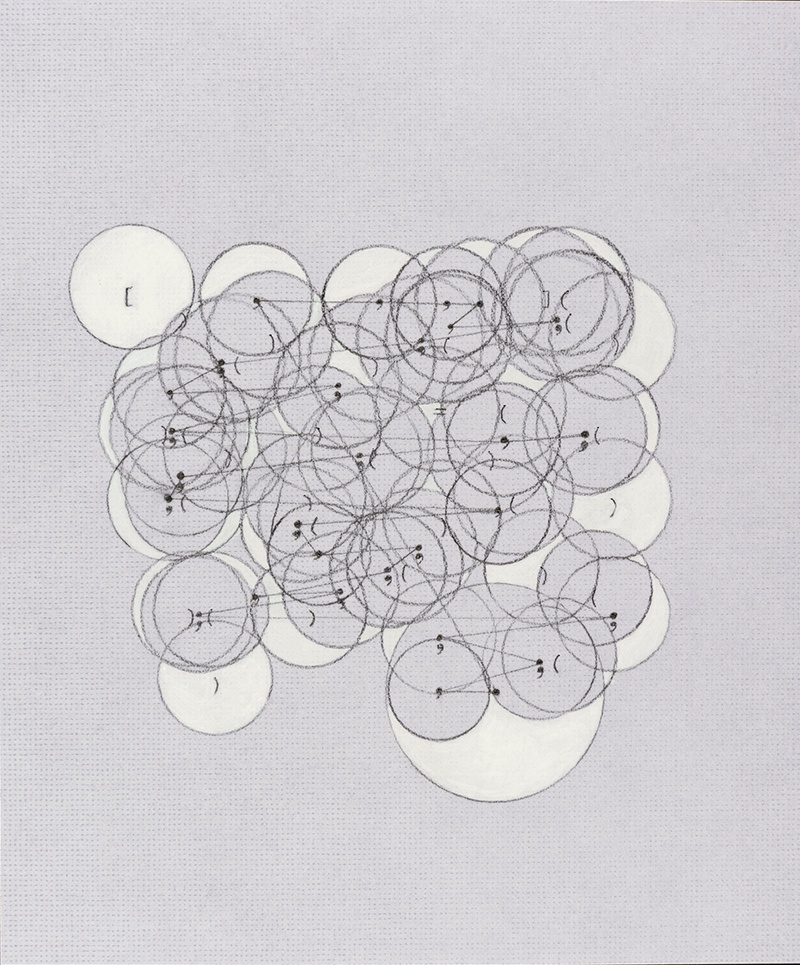

Trail 2012 a

In the current artistic environment there is so much pressure. Academia and the market demands you to produce, and your peers ask questions like “What are you going to do next? Is it possible to have the time and space to let an idea or project take its own shape at its own pace? Is this something you struggle with?

Anyone who says that there is no pressure from academia or the market would be quite naïve. What is important is what do we do with that. Deadlines are something to discuss and are inescapable. At the same time: “what’s next” is mainly a pressure from a “productive art” position. There is an inescapable contradiction in our ways of doing art. Many theorists, like Gayatri Chakvarty Spivak, say that we should embrace that paradox. I agree, of course, but I also believe in intellectual honesty as a starting point. I mean, at least to make the means of production transparent for the reader or the audience, to give them all the roots of a project so that at least they can read it in its completeness.

Sounds very simple, but it’s actually very hard to achieve. A simple example could be that many writers don’t know where their books are printed and under what conditions. Those conditions are part of your artifact. Whether you want it or not, your novel, your installation, your collected poetry, or your sculpture are objects (even when these are virtual), and they have a back story that defines them. Another example is that we forget so easily how our computers, the principal tool of our artistic work, are produced and again, under what conditions.

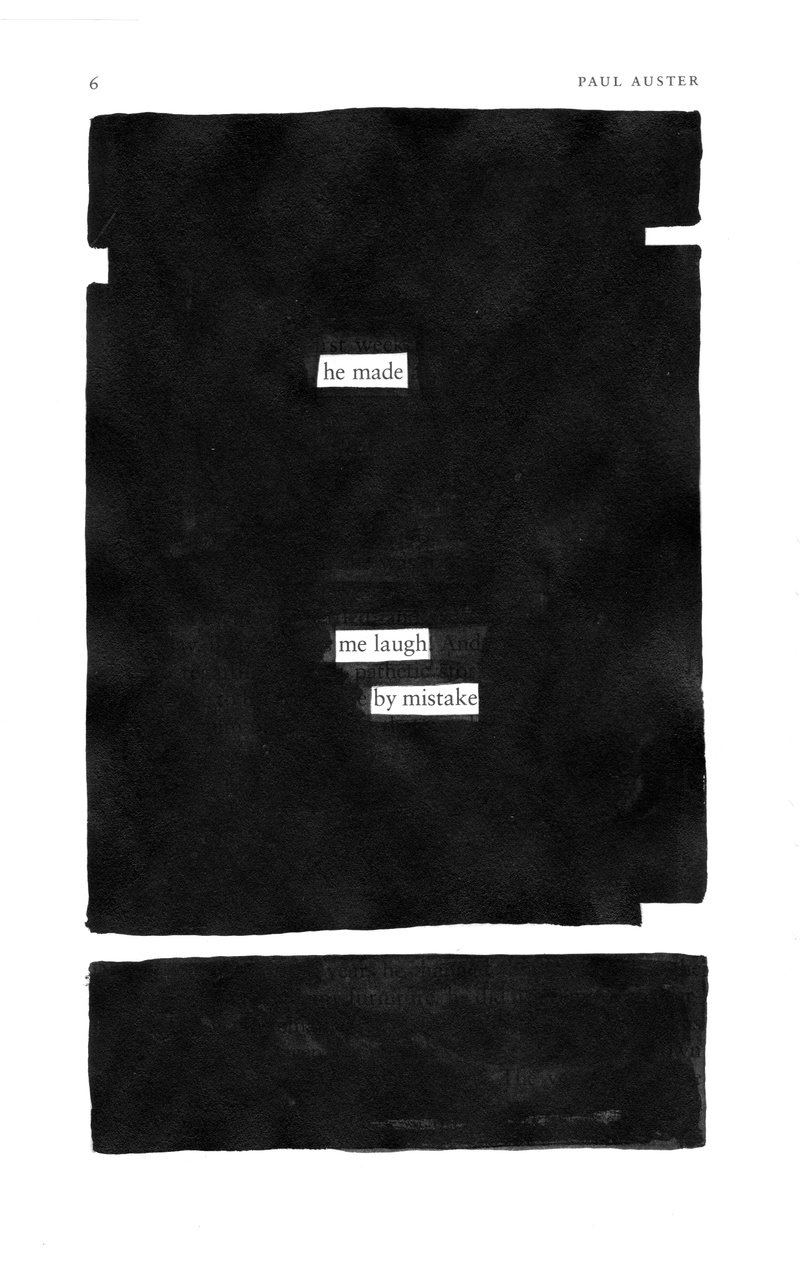

Diagram of silence #8 (Mutam, Anne Carson) 2018

You mentioned in a talk that “the artistic practice of today requires that we know how to write.” It’s important that artists know how to manage the written language in their work because, if they don’t, then someone else will take care of it. For example, the curators. Not all artists are used to this. It must be hard to write about your own work because it puts you in a vulnerable position. How can an artist or someone who is just starting in their practice develop this skill? Is there some process or what would you recommend to new artists?

I think we need to accept as visual artists, for once and for all, that the text is and will always be part of contemporary art. And then, what are we going to do with these text spaces? Statements, audio guides, guided visits, curatorial texts, mediation texts, title and description of the pieces, and catalogues are all spaces that we can make our own. Whether we want it or not, they end up being part of the artwork, or the experience of whoever wants to enter the artwork. These text spaces can be appropriated in different ways by us and not used always in the same way (as we do) or in the way that’s indicated by institutions or the market. We need to be aware of those spaces and propose something in regards to them.

My recommendation to young artists is to always collectivize their work. To think among others, with and for others. To understand what the other is looking for and try to think in that direction and not in the direction you would go with your own work. And to read a lot! Unlike what many people think, the act of writing or reading is not solitary, on the contrary. It is quite common to hear that from many colleagues, of course there are solitary moments, but we read to be among others, we write and make art to remember our being with others, to get in touch with others, to understand our present.

The relationship between an artist and a curator is complex because there’s a labor imbalance where frequently the curator receives a salary and the artist doesn’t. Additionally, both have to consider the public and the space where the work will be and how it will be “consumed.” What is the ideal relationship between an artist and a curator and, are there certain rules or agreements that should be established from the beginning?

The collaboration between an artist and a curator is always different and it changes from project to project. In that conversation I was talking of the working conditions of the art world in México. A collaboration between a curator and an artist most of the time is mediated by an institution, a museum, a gallery, an independent or a public space, or a government agency. What seems to be unbalanced is to convince the institution to consider a salary for the artist. Usually, they give a production fee for the project, that you use to buy materials and produce your artwork, and that’s it; and the curator has a fee for their work. And this doesn’t happen only in the visual arts. For example, magazine editors have a salary, but many times, there is no fee for the editorial collaborators. That’s the imbalance I meant.

To me, the ideal relationship between a curator and an artist is exactly the same I suggested before: thinking together. When a curator and an artist work together, they might put two ideas on the table, or two projects that need to find a way to coexist and become one. So the best way is to think together, to find common ground.

Most of us have mixed text and images to present ideas and information with PowerPoint. It is used in classrooms, conferences, Ted Talks, even to present military strategies. Schools and offices are designed with the idea that people will be in front of a screen. Do you use it in your classes? What do you think about the use of this software and the way it shapes how ideas are presented? Do you think it can lead to process information in a sequential way rather than a comparative way?

I never use PowerPoint when I teach. I’ve always been kind of against it because I don’t like how people use it. In my classes I only show images, I use text only when it’s indispensable. I do handmade maps with central concepts and scan them as well. Of course, it depends a lot on the type of subject or the type of class I’m teaching, but in my case, it’s important to give a certain weight to the images; when they go along with text there is an inescapable hierarchy and the text ends up determining the images. So I prefer to liberate images from text in the projection.

PowerPoint is a program that has an interface designed by a corporation to be used with certain limitations. We use computers and create millions of files, images, texts and we do exhibitions, books, and millions of things with those archives, but we don’t know how to see what’s behind those friendly interfaces. The future, or part of the future of editing, as well as the future of visual arts and literature, will be in understanding the programming codes, in involving ourselves in what is behind those interfaces, in making them transparent somehow. Only if we manage to understand fully the tools we use to create, we will be able to dismantle the systems we are criticizing as well. We take for granted our writing tools and we create our experimental or confronting images without thinking how much they are limited.

Trail 2012 b

What is something you wish someone told you when you began to make art?

It’s a tough question. I have been teaching for the last 15 years and I always know I could do better. I learn a lot from my students, and I’m grateful to them. But even though I know how difficult it is to address all the students’ needs and expectations, I would’ve appreciated advice about feminism at my university and a stronger women’s circle around me where I could go and talk. I have the impression that I read all the things I should have read too late! And I still have to read a million more! But besides the reading materials, I feel I could’ve avoided some bad experiences, or at least understand them better, so I didn’t feel so lonely. Knowing more about it I could have been more helpful to my friends as well.

Is there a doodle we can do to avoid the fear of a blank page?

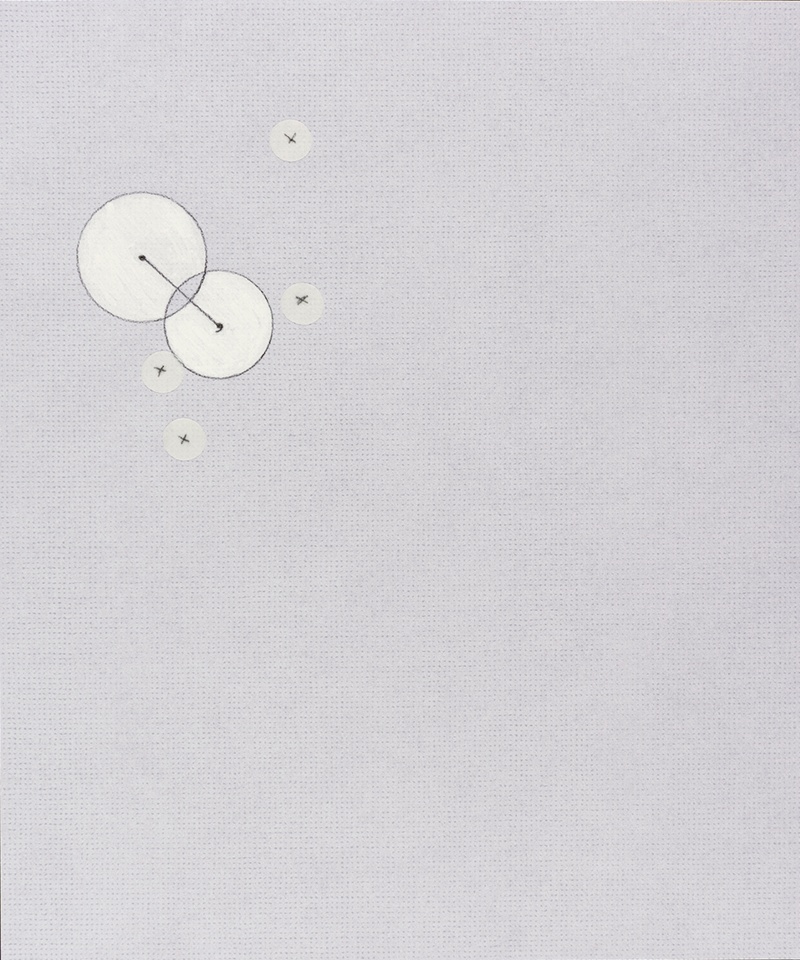

**This drawing represents the Venn Universe. To draw a Venn diagram, we first draw a rectangle which is called our “universe”. In the context of Venn diagrams, the universe is not “everything in existence”, but “everything that we’re working with right now.”

Verónica Gerber Bicecci recommends:

- I recently became addicted to hearing podcasts while I cook, I deeply recommend: Radio Ambulante and Las Raras.

- Also, I found a very useful and depressing web page: Atlas for the End of the World that we really need to pay attention to.

- Finally, I started this year by reading a book I should have read a while ago: Feminism is for Everybody, by Bell Hooks.

- I highly recommend the book Antígona González by Sara Uribe, recently translated to English by John Pluecker.

- Finally, I just had the opportunity to watch the movie Donna Haraway: Storytelling for Earthly Survival (directed by Fabrizio Terranova), it’s a beautiful film, intelligent and full of hope.