On community, protest, and public space

Prelude

Shannon Finnegan is a multidisciplinary artist making work about accessibility and disability culture. They have done projects with Banff Centre, Friends of the High Line, Tallinn Art Hall, Nook Gallery, and the Wassaic Project. They have spoken about their work at the Brooklyn Museum, School for Poetic Computation, The 8th Floor, and The Andrew Heiskell Braille and Talking Book Library. In 2018, they received a Wynn Newhouse Award and participated in Art Beyond Sight’s Art + Disability Residency. In 2019, they were an artist-in-residence at Eyebeam. Their work has been written about in C Magazine, Art in America, Hyperallergic, and the New York Times. They live and work in Brooklyn, NY.

Conversation

On community, protest, and public space

Artist Shannon Finnegan discusses the ways in which their work addresses issues around disability, accessibility, and ableism, and why the idea of community is so central to their practice.

As told to Amelia Brod, 2868 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Inspiration, Education, Collaboration, Adversity, Identity.

I’ve been a fan of your work for a long time, and I’ve seen it evolve at a very rapid pace in the past couple of years to be increasingly focused on disability, accessibility, and building community. I was wondering if you can talk a bit about that shift.

I had this realization that I wanted to make work for other disabled people. I wasn’t able to learn a lot about myself as a disabled person from mainstream media or mainstream environments, but I learned so much about myself from other disabled writers and artists. Once I realized that I wanted disabled people to experience my work, I felt like I had to build the structures that could make that happen because it’s not always possible in existing art spaces. That was how I became interested in accessibility.

I think part of how ableism operates is by isolating disabled people and by telling us that our experiences are these personal and private things. For me, creating connections between disabled people becomes political and a potential force for dismantling ableism. Part of how I understand accessibility is that it makes that connection possible. It’s how we’re able to be together, either in physical space, digital space, or through shared experiences.

Caption: Do you want us here or not 1, 2018 Image description: A blue bench with hand-painted text that reads, “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long. Sit if you agree.”

Caption: Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at the Vessel, 2019, photo by Maria Baranova. Image description: About 40 people posed in front of the Vessel sporting neon orange, Anti-Stairs Club Lounge beanies and holding Anti-Stairs Club Lounge signs.

I see several of your projects, like Museum Benches [a series of blue benches with text on them such as, “This exhibition has asked me to stand for too long”], as invitations to build solidarity and community. Can you talk a bit about how and why you invite people into your work?

That project makes concrete things that many disabled people would automatically do, like taking a seat in a gallery space. I wasn’t really thinking that much about non-disabled visitors when I created that piece. I was really in this mode of asking, “What’s for us? What can support our experience?.” When I go into the traditional gallery space the selection of seating sends a message that the space does not think that most people want to sit or need to rest. Through that work I wanted to acknowledge, “Yes, this exhibition has asked me to stand for a really long time and I want to sit down.” I wanted to affirm that feeling or need, “Yes, of course, have a seat.”

[Related focus: Building a community →]

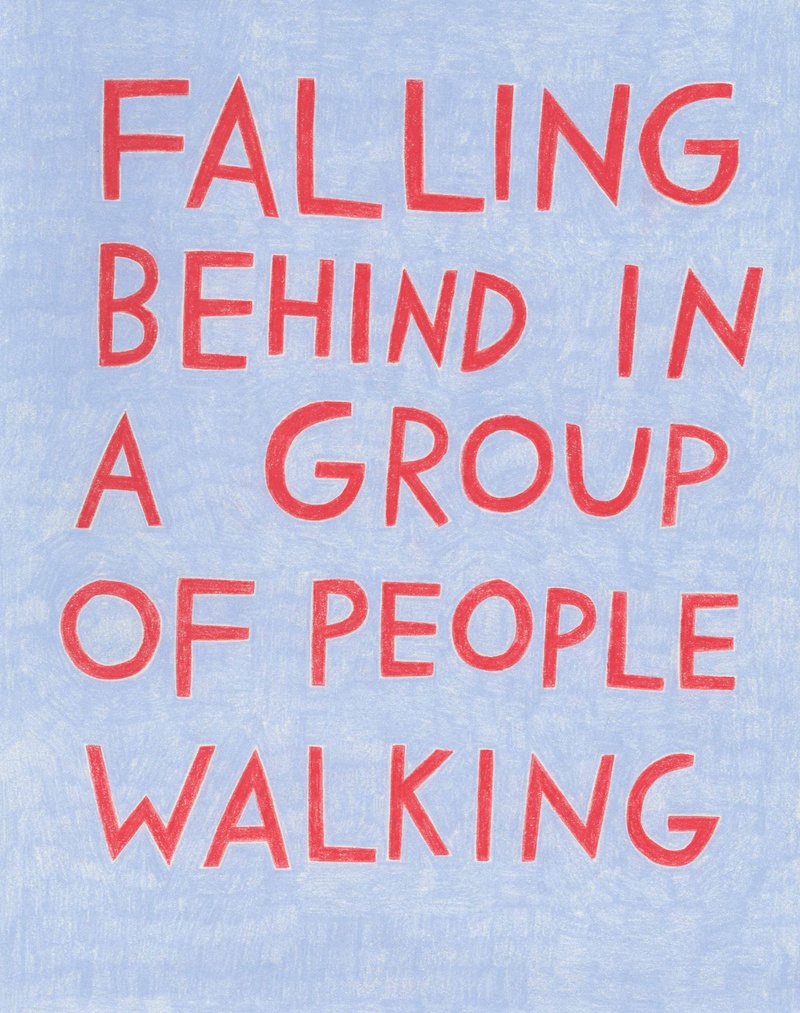

I’ve been interested in the ways that we often think about protest in really ableist ways around marching and standing up for something. But then there is also this really rich history of sitting as a form of protest. As a disabled person, it’s really interesting for me to think about forms of protest that involve comfort or rest. I’m starting to think through this idea with these benches. It’s this way of giving voice and also providing rest.

Your projects also happen in very different contexts, in public spaces, museums, project spaces and many other places. How do you decide on the right location or the right community for the work?

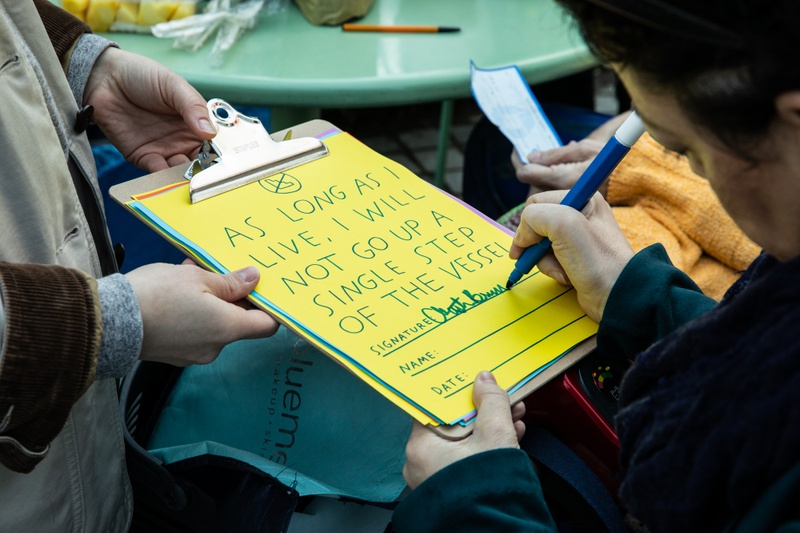

I don’t think it’s always that deliberate. Sometimes there’s a space that prompts the project. For instance for the project Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at “Vessel” [a club lounge that included seating, cushions, snacks, and custom fluorescent-orange beanies worn by fifty disabled and non-disabled people who all pledged, “As long as I live, I will not go up a single step of the Vessel.”], it was just so frustrating to see this new $150 million project be so inaccessible because we’re so often told that things can’t be accessible because there isn’t a budget or because it’s a historic site. It was just so enraging that it prompted the project. And it dovetailed with questions I had been asking myself: as an artist who’s interested in centering disabled audiences, how do I respond to an inaccessible space or intervene?

Caption: Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at the Vessel, 2019, photo by Maria Baranova. Image description: A close-up of Christine Bruno signing a pledge: “As long as I live, I will not go up a single step of the Vessel.” The pledge on colorful paper, riso-printed with blue hand-drawn text, and has a crossed-out-stairs symbol at the top.

Image description: A group of about twenty people lounging in front of the Vessel. They are sitting, chatting, and reading. All wear bright orange Anti-Stairs Club Lounge beanies.

There were a lot of constraints in terms of who could participate in that project. I didn’t want to announce it publicly because I didn’t know how Related [the real estate company that owns and operated the Vessel] would respond, so in this case I was activating my personal network. I was focused on disabled people and non-disabled people who I knew who were invested in disability culture and accessibility, or who were already involved in that work because I didn’t want the project to be about explaining why we were there or trying to justify why we were frustrated or upset about the Vessel. I wanted it to be a chance to be together in that frustration and anger. I also wanted the project to demonstrate how I want to use public space—I want to be able to gather, I want to be able to hang out, I want to lounge. The best part of the protest was thinking through questions like, ”How would we want to use this space? What do we want from public space?” And then demonstrate that through the Club Lounge.

I’ve learned from Kevin Gotkin, Aimi Hamraie, and others not to think about a singular “disability community” but to think about “disability communities” in the plural. I want to try to make projects that invite people in, but also to acknowledge that the idea of a universal design or universal accessibility always erases people who can’t or don’t want to participate. And as an artist I’m always learning about new ways that I can shift my practice or rethink ways that I’m working around my own bias.

I’m going to shift gears a little to talk about Alt-Text as Poetry [Alt-text is an essential part of web accessibility, it makes visual content accessible to blind people and people with low vision. It is often overlooked altogether or understood through the lens of compliance, as an unwelcome burden to be met with minimum effort. Alt-Text as Poetry asks—how can we instead approach alt-text thoughtfully and creatively?]. Correct me if I’m wrong, but I understand the project as being specifically for artists and the art industry. Can you talk about this project and why you think it’s important to share knowledge and move the conversation forward in the art world specifically?

Alt-Text as Poetry is a collaboration between me and Bojana Coklyat who is also a disabled artist. I think the project started because of our independent interests in accessibility and moving away from this compliance-oriented approach to accessibility to think about access as ongoing, creative, and generative. And for me as a sighted person, I was thinking about my training in the arts and whether working visually was important. And when I do work visually, I want to be proactive in making that work accessible.

Image Description: Lukaza and I semi-posed in the Nook holding work from the show. The work is displayed on two lazy susans and on a built-in shelf. Above the shelf is a text piece that says, “Welcome to this seating-centric space.”

Caption: Nook Poster, 2020. Image description: In lime green, my loose attempts at drawing the objects in the show. They are mostly different lumps and shapes. Overlaid are the featured artists’ names in dark blue: Alex Dolores Salerno, Sandra Wazaz, Christine Sun Kim, Jeff Kasper, Carly Mandel, Rebirth Garments, Jillian Crochet, and Pelenakeke Brown. “And Yo-Yo Lin!” is added on like a sticker.

As I started to research description practices and alt-text practices [alt-text is the written copy that appears in place of an image on a website. This text helps screen-reading tools describe images to blind and low-vision readers], I felt frustrated with how limited the dialogue was around it. I had the sense that we need more people thinking and talking about it. The workshop is not about Bojana and I coming in and saying, “This is how you write alt-text,” but about trying to gather people and get them interested. We do this by giving them enough information to understand the complexity or issues that come up, while also giving them a sense that it requires ongoing practice, collaboration, and learning.

One of the ways that we talk about the project is this idea of a collective toolkit that we’re trying to build. In the context of art, people are more familiar with the idea that people are bringing different interpretations to what they’re seeing and understanding it in different ways. So that’s been helpful just in terms of getting people to understand that there is a huge range of what people are seeing, what people are noticing, how they put what they’re saying into words, what words they’re choosing, and their tone.

Can you talk a bit about why you think it’s important to build community among your peers?

I’m still at the beginning of really exploring this, but what I’ve realized is that my work is interdependent with other disabled artists’ work. What I make would not be possible without the work of so many peers—their thinking, making, and writing. So I don’t want to be in situations where my work is understood in isolation, and I’ve been trying to think about how I can build that into the structure of my work, to acknowledge those connections.

It also comes from this place of total excitement. There’s incredible work being made right now and it feels like I’m often going into spaces where people aren’t familiar with it. So it is also just a way of celebrating all of the projects, objects, and artworks that I feel excited about.

When you’re developing a project that involves community, what are the key steps that you take to develop the project?

So for Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at “Vessel”:

-

I heard about the plans for the space through disability Twitter and then I pretty immediately knew I wanted to do a project like Anti-Stairs Club Lounge at Wassaic Project, and so figuring out how to do an iteration of the project.

-

And then I read about it online—Kevin Gotkin had an amazing essay that really helped me understand what was happening with the Vessel.

-

And then I did a couple of site visits. I visited, when it was under construction and was still closed just to see it in progress and then I also visited once I could move closer to the space.

-

I was on Hudson Yards’ email list, I was following them across social media platforms. I was reading all of the coverage that was coming out. That was a challenging project because the turnaround between when the space opened and when we were there was less than two weeks, and I wanted it to be this immediate response to the opening so I was trying to glean any information I could about the space before I could access it. I asked my partner to email them about accessibility in the Vessel because I wanted to understand what their official response and policy was around that.

-

And then getting really detailed about walking through the logistics from an access perspective, but also just from a party planning perspective. I was just trying to find any information and then in parallel I was emailing people tons of information about what to expect, which is something that I’ve learned from disability communities is this idea of just being really transparent about what I expect from the space. I emailed them about what I didn’t know, what I had planned, and what I felt uncertain about. And thinking through different issues of like, “Okay, who’s going to be the point person if someone can’t find where the group is?” or, “Where are the bathrooms?”

Caption: Alt-Text as Poetry Workshop, 2019, photo by Christine Butler. Image description: Bojana Coklyat speaking while I look on. The monitor behind us shows a slide that says “Intent”. Workshop participants are seated with worksheets and writing utensils in front of them.

Caption: Do you want us here or not for Disarming Language at Tallinn Art Hall, 2019, photo by Karel Koplimets. Image Description: Two chairs fitted with blue cushions. Both cushions have white handwritten text. One reads, ‘There aren’t enough places to sit around here. Sit if you agree.’ The other reads, ‘Siin ei ole piisavalt istumiskohti. Istu, kui nõustud.’

Along those lines, what are some of the challenges around building community or identifying who your work is for?

One thing I struggle with is knowing that some people are not going to be able to participate because of access issues. I don’t like to disappoint other disabled people, especially if it’s in ways that I know they’ve been disappointed a million times before. So one of the biggest challenges for me is continuing to do ongoing research through conversation and knowledge building and asking different questions like, “What are different ways I could be working? What are different ways I can be thinking about accessibility?” I know that I will make mistakes and that some things won’t be accessible and that I’ll learn from that and then I’ll iterate. But also trying to do as much learning as I can.

[Related reading: Poet and artist Robert Glück on authenticity and community →]

Along those lines, your work could be interpreted as education, design, or community building. What do you think the advantages are of approaching these topics through the lens of art and creativity specifically? Does it give you more flexibility or room to experiment?

I appreciate the “no rules” aspect of art. I can imagine spaces or experiences that wouldn’t happen in spheres that are more rooted in what’s practical or what resources are allocated. I’m able to be in this more exploratory, imaginative, and playful space. For example, artists are allowed to ask really open-ended questions that don’t have answers. I think Alt-Text as Poetry can easily be understood as a type of access consulting and we’ve been really careful to say, “No, this is an art project,” because we don’t want people to come in with the expectation that they’re going to get answers from us. We want them to have a more open-ended and complicated experience.

I think those are amazing reasons! I feel like people are always trying to figure out why art and creativity are important and it’s very hard to articulate.

My work is often understood as design, or as related to design, and I think that’s because culturally we understand access as a design issue rather than as a community-building issue or as an art issue or as an education issue. There are really interesting historical examples of access that are rooted in design, but I think design has also had a really negative impact on access because it has put designers who are often non-disabled people in this savior position. I’m still figuring out what my relationship is with what’s going on in design.

Caption: My pace is the best pace for me, 2017. Image Description: Hand-lettered text that reads, ‘Falling behind in a group of people walking.’ The text is in red colored pencil on a shaded, light-blue, colored-pencil background.

All image descriptions written by Shannon Finnegan

Shannon Finnegan Recommends:

-

Skin, Tooth, and Bone: The Basis of Movement is Our People, A Disability Justice Primer by Sins Invalid

-

Everything Mia Mingus has written

-

This working definition of ableism by Talila “TL” Lewis in conversation with Disabled Black and other negatively racialized folk, especially Dustin Gibson; updated January 2020

-

@museumseats on Instagram

- Name

- Shannon Finnegan

- Vocation

- Artist

Some Things

Pagination