On the creative power of fleeting moments

Prelude

For nearly three decades, German artist Wolfgang Tillmans has challenged and expanded the field of contemporary photography. His work takes the form of complex installations filled with pictures capturing the pulse of youth culture and the places, people, and moments he encounters. His experimentations with abstraction, scale, and methods of image-making that abandon the camera have helped push forward the limits and possibilities of the medium. Tillmans pays particular attention to the architecture of the spaces where his work is shown, bringing together prints in assorted sizes and orientations, which he variously displays in frames or simply clipped or taped to the walls. In recent years, his practice has expanded to include video and music. Moon in Earthlight, the artist’s first full-length album, is presented in his exhibition, Concrete Column at Regen Projects in Los Angeles.

Conversation

On the creative power of fleeting moments

Artist Wolfgang Tillmans discusses paying attention, working from a personal archive, and why cameras are radical tools.

As told to Katy Diamond Hamer, 2024 words.

Tags: Art, Music, Process, Inspiration, Focus.

You recently opened a new exhibition, Concrete Column at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, and also released, Moon in Earthlight, your first full-length album. I’ve heard several of your musical compositions over the years, and I hadn’t initially realized that this release was your first official collection of music.

Yes, it’s true. I guess I like the EP format, because something with three to five songs seemed like a good format that doesn’t have too much weight, baggage, or obligations. I’ve been wanting to do something album length for a while, but it took its time. Then this summer, I decided to revisit a project I worked on in 2017 at the Tate Modern in London.

Tell us about that project.

It was a 100-minute sound piece presented in a gigantic oil tank, consisting of a whole variety of different sources of sound, from studio recordings to field recordings, to spoken word, to just on the spot cuts of jams. They were all flowing into each other and I thought it would be a good listening experience. But it wasn’t really a [good] spacial experience. I used 20 programmable lights to-create a choreography of sorts with video as well.

In the years following, I worked on more clearly defined songs. I put this mix of original material on the side for a bit, only to come back fully this summer to create this 53-minute album.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Geos 2, 2021, Inkjet print on paper, clips, 54 3/8 x 81 1/8 inches (138 x 206 cm)

I was wondering if you could talk about the song “Device Control” from your 2018 exhibition at David Zwirner titled, How Likely is it That Only I am Right in This Matter. Did that audio composition play a role into what I’m hearing on Moon in Earthlight?

That song came from an outpouring of observations I made in the previous couple of years, mainly 2014, ‘15, ’16. I observed a shift in consumer telephony and in the marketing of smartphones. Now it is all a matter-of-fact, but at the time it seemed so wild that mobile phone companies were advertising that you can live stream your life. It struck me as this seismic shift where there is more recording possible than there’s ever time to view it all. There is an absurdity to that, not of recording absolutely everything, but not having actually a place and time to look at it all.

I could be of course a contrary pessimist and somber about it, but I also saw the humor in it, because it’s just so incredibly absurd. One morning in 2016, I woke up and wrote alternative lines to mobile phone ads and strung them together in one flow and recorded them. The whole thing is one take.

I took it to my musical collaborator, Tim Knapp, and said, “Hey, can you pull this into a grid?” I had some instrumental suggestions for it, and he took them, and that’s the origin of Device Control. It was literally I guess a longer term cultural peripheral observation, then crystallized in one 10-minute moment.

As you were speaking, it reminds me of the act of taking a photo, and how the photo is really one take. You can capture one moment, and then you can take additional photos, but then they most likely will be different. It’s interesting that you did that with the audio component, just one take to do the recording.

I’ve also found it curious working with musicians, and that they often don’t have a particularly strong interest to record everything that goes on in a jam. They feel that, “Oh, we can put that down at a later stage when the idea is more solid or more refined.” Personally I have always felt, that for me as a photographer, there usually isn’t a second take. The ingredients that make up a photograph are so multiple and so variable that to get all of them exactly in the same place or to speak the same language is very difficult. It doesn’t mean that [the next moment] is necessarily worse, but it’s about making a decision, “This is the one.”

Yes, exactly, moments are fleeting.

I do believe that there are deep and meaningful things happening in fleeting moments. Not that every sketch and every shoddy little thought or gesture is always a great thing, I’m not saying that. It’s not clear what will ultimately be there in the moment, that it has great poetry and a great coexistence of what I call chance and control. It’s in this space where I see my work constantly oscillate, sort of in suspense between, and I try to allow chance and at the same time control as much as I can. Knowing when to stop is so important. When do I dare stop controlling? When do I allow things to happen?

Installation view of Wolfgang Tillmans’ Concrete Column at Regen Projects, Los Angeles, November 6 – December 23, 2021. Photo: Evan Bedford, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles

When I was listening to Moon in Earthlight, I jotted down some of the lyrics. A phrase that stood out was, “Set your sights to tomorrow, it’s not too late, it’s not too hard, there’s more that connects us than divides us.” You say that in repetition, and I feel like the lyrics are very sculptural. The music kind of holds the sound of the vocal component, and I kept thinking about it as an audio sculpture. The lyrics are very poetic and timely. Can you speak to that a bit, the language you use in this album?

It’s hard for me to say, “Yes, I like what you said,” because I feel like [the language component] can only exist in a free and poetic way if it’s not too prescribed, intended or planned. It’s true that my main point of departure is language. Maybe the repetition of words that makes the very presence of the sentence in the mouth or in the ear and space … Well, it’s an incredible miracle that they exist and that they mean something, and that they connect to something in other people’s brains.

I have a great respect for it, and at the same time, take pleasure in playing with that. I work with a library that’s composed of 30 years of jotted down lines, titles.

Wolfgang Tillmans, spot reveals, 2020, Inkjet print on paper mounted on aluminum in artist’s frame, 32 x 25 3/4 x 1 1/4 inches (81.2 x 65.7 x 3.2 cm)

I am also curious about your cover of “El Condor Pasa,” a Peruvian song with an arrangement and lyrics made popular in 1970 by Simon and Garfunkel.

I don’t know where that cover came from. I have always liked singing it. Besides the solo work and songs that I make with Tim Knapp in Berlin, there’s also a band constellation of six musicians that I perform with. There are two from New York, one from Rhode Island, one from Bogota, Colombia, myself and Tim. We first came together in 2016 on Fire Island and have sort of had annual reunions and maybe a concert or two a year. El Condor Pasa was recorded live and that version is on the album. I’d liken it, to photography, in the same way that I also don’t shy away from looking at the sunset. If I see a sunset, I can see a cliché or I can see a direct experience. The version of this song by Simon and Garfunkel is loaded, as people find it to be [connected to a specific] era and considered possibly quite naïve, but that is what has has touched me about it. Somehow it was curious to have that song sit in the midst of others with original compositions.

I’m happy you included it. Many of the other songs on the album, have what could be construed as a call to action. I walked away thinking about the right we have to hope for a happy life, and how collectively we’ve got to be stronger than this.

It’s something that is close to me, I’ve felt very affected by protest songs, by socially, politically engaged music, and at the same time, of course it’s a thin line between being like, “What can I do, and how does it sound from my position?” I don’t want to be too earnest, and sometimes get close to that line. A sense of play and absurdity is something that is to me as close and important as spelling out an opinion or a sentiment that may be too close, too direct for some.

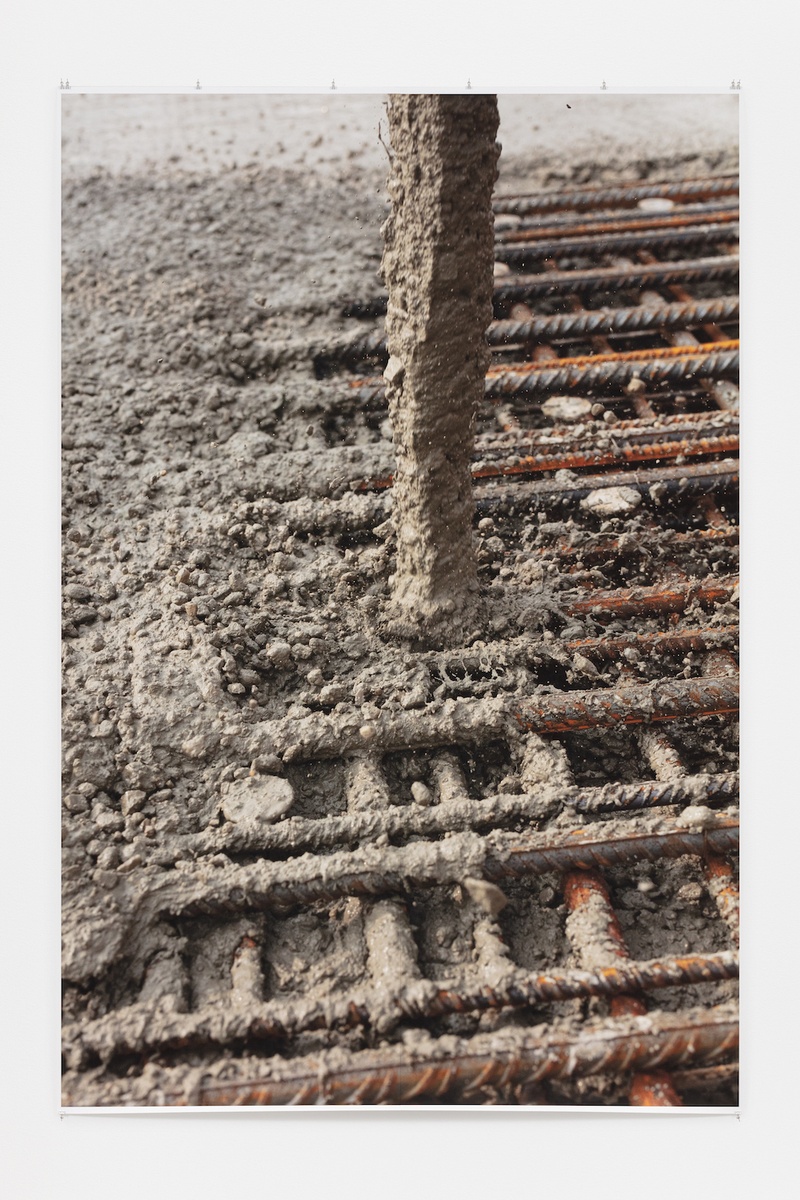

Wolfgang Tillmans, Concrete Column III, 2021, Inkjet print on paper, clips, 149 3/4 x 100 1/8 inches (380.5 x 254.2 cm)

Wolfgang Tillmans, Zoma construction Addis, 2019, Inkjet print on paper, clips, 54 3/8 x 81 1/8 inches (138 x 206 cm]=)

What can you say about the photographs in Concrete Column?

The works in the show at Regen Projects have a thread that I would describe as studies of material. The two main pictures are of concrete being poured, and they’re photographed at such high speed that the liquid poured concrete becomes the solid column in the photograph. Then there is a picture from 1987 of somebody jumping off a rock, and one from 2021 of a mysterious rock on a beach in a scale, impossible to understand in the photograph. One can’t tell, is this huge or is this small? Three large scale photographs called “Silver” refer to the silver, physical matter in the photographic process. Two other pictures are of a mobile phone and a flat screen, inviting those to look at the elements of screens.

Other photographs, include the Sahara Desert, as sand is the raw material for computer chips, ultimately glass and frames. It really doesn’t make any literal sense. One can’t say, “This leads to that,” but they are all connected in a way that feels relevant to me now in a matter of careful observation, of valuing what matter is and understanding what surrounds us, and how we consume. Sand is a huge issue nowadays, as it’s difficult to get sand for concrete. And the concrete itself is a huge issue because it is one of the main drivers in carbon pollution. Even though I’m mainly known for pictures of people, this [selection of pictures] is more calm, somebody said somber, but not in a sad way.

Wolfgang Tillmans, Silver 167, 2014, Inkjet print on paper mounted on Dibond, aluminum in artist’s frame, 88 1/4 x 67 3/8 x 2 3/8 inches (224 x 171 x 6 cm)

Then there are also four astronomical pictures, one is the cover of the album, The Moon In Earthlight, and another is that of the sun seen through a telescope whilst the planet Venus was crossing the surface. I guess astronomical contemplation has its own emotional valor.

Something that strikes me about the medium of photography, is that even though it is so technical by its apparatus, it seems incredibly psychological in how it operates in the hands of different people. The same camera produces completely different works by different people. That is something one accepts lightly or doesn’t think much about, but it is actually quite radical.

Selected Wolfgang Tillmans:

Moon in Earthlight - Physical release CD and 12” vinyl upcoming

The video for “Insanely Alive”

“Fire Island” (2015), Galerie Buchholz, Photography, inkjet print, framed, 10 + 1AP

Exhibition walkthrough of Concrete Column with Wolfgang Tillmans, Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Filmed Saturday, November 6, 2021

“Lutz & Alex climbing tree,” photo, 1992

- Name

- Wolfgang Tillmans

- Vocation

- Photographer

Some Things

Pagination