On establishing a feminist art space and making it sustainable

Prelude

Sarah Williams is a co-founder and Executive Director of the Women’s Center for Creative Work. Born and raised in Hawthorne, CA, Sarah returned to Los Angeles in 2006 to attend USC’s Curatorial Practice in the Public Sphere M.A. program after receiving a B.A. in Art History from the University of California, Santa Cruz. Since then she has been producing projects, exhibitions, programs, events, and publications with ForYourArt, WCCW, CLOSING, and the Art Book Review. She serves on the boards of ProjectQ and Common Field, as well as the Elysian Valley Riverside Neighborhood Council.

Conversation

On establishing a feminist art space and making it sustainable

Executive Director Sarah Williams on how the Women’s Center for Creative Work in LA came to be, why a nonprofit model made the most sense, taking on an executive-level leadership position for the first time, and why bigger isn’t always better when it comes to arts organizations.

As told to Willa Köerner, 3711 words.

Tags: Art, Culture, Fundraising, Beginnings, Collaboration, Business.

How did the Women’s Center for Creative Work (WCCW) in Los Angeles come to be—from the initial idea, to building the momentum to get it off the ground?

We started with three co-founders: myself, Katie Bachler, and Kate Johnston. I knew Katie through grad school, and Kate knew Katie from undergrad, and we were all working on projects that, in retrospect, had a connection to what the future women’s center would focus on. We got together and started talking about ideas, and how we might collaborate.

We saw the show Doin’ It In Public, which was at Otis College of Art and Design here in LA. It was this archival history of the historic women’s building in Los Angeles, which was operational between the ‘70s and the ‘90s. We were just blown away by the breadth and the scope of its history—this very deep, feminist, arts-organizing history that we were relatively unaware of, even though we had all gone to liberal arts schools. After seeing that show, we became really interested in asking, “Where does this intersection between feminist practice, art making, and design exist today?” Back in 2012, we were not really finding it. Now we see a lot more of it, but this was before there was this kind of wellspring of it that we have now.

In the beginning, it all started as a series of dinners. We called them Women’s Dinners, and we did the first one in the desert, because that’s where Katie was living at the time. We invited everyone who we thought would be interested, expecting maybe like 20 or 25 people to show up. 60 people ended up coming, and it was an incredible experience. Really from that point forward, everyone was like, “Okay, what’s happening next?”

From there, we could really feel that the fire was lit, and this community was starting to form. People who came were advocating for something more ongoing, and an ability to have these connections and conversations more frequently. So, we started doing some strategizing around that. We got a residency early on and just started practicing this kind of programming and organizing as we were growing. Maybe six more months after that dinner, we were feeling really excited. We were like, “Let’s just do it. Let’s get a space. Let’s get organized and make that happen.”

So we put together an advisory board and started talking to people, like, “We want to get a space. We want you to help us. Let’s do this.” But those people then had a bunch of questions for us. “Where is the money going to come from? What’s the structure, and how will it run?” So we were like, “Okay. We maybe need to take a step back and think this through a little bit more.”

So we started this project called Yearlong Laboratory. We broke the year into four parts, and over each quarter, we focused on researching histories, communities, economies, and then space. Within those focuses, we researched feminist art making and organizing histories, and community-focused thinking, asking “Who is this for, and how will we do it?”

Sort of serendipitously, towards the end of that ideation-focused year, we got a grant for $10,000 from spART, which is a granting entity focused on social practice art making. That money basically let us put the first and last month’s payment down on a space. Beyond that grant, we really had to rely on all of the people who had been pushing this project forward. We launched a membership program where we were like, “If you really want to see this happen, it has to be a collectively supported project. None of us are coming from a position to bankroll this.”

In that first ask, we got about 100 members who committed to contributing monthly. That basically got us through the first year and a half or so as we launched the space and stabilized.

How does the organizational structure work now? At this point, it seems like it’s a pretty fleshed-out organization with actual employees—can you share how that took shape?

We are a nonprofit, so that’s our business structure. We have eight employees right now, and I’m the executive director. Despite being a nonprofit, we very actively try to resist a traditional hierarchical way of working. It’s very collaborative. We try to have very clear job descriptions and clear processes that allow us each to make decisions within our own lane, and move things forward. But big decisions are produced very collaboratively each year. It’s been an exciting way to work.

How did you decide to become a nonprofit? Were there other models you were considering, or was that really the only model that made sense?

We were considering other models, especially in that yearlong laboratory. We were, and still are, very interested in cooperative models. But there are a decent number of grants that are only available to nonprofit arts organizations, and it didn’t feel like we had a way of making enough money to support this kind of a project outside of receiving donations and grants. So financially, the nonprofit model felt like the right way to go.

But at the same time, we’re interested in challenging that. We’re a very conscientious nonprofit, in terms of how we work with our board and how we structure our staff and all of that. We try to break down some of the worst aspects of nonprofit management and find better ways to operate.

In terms of your funding model, what percentage comes from membership versus grants, and do you have other revenue streams that help keep things going?

Yes. We do have a chunk of earned income outside of grants. A lot comes from membership. We have about 550 members now. That produces about 15% of our operating budget. We also do things like space rentals, and we have a little bit of merch. We do some programs that cost a little bit to attend, and so we earn some money that way. We also just launched Co-Conspirator Press last year, so we’re selling books through that. That’s actually been a runaway hit in a lot of ways.

Then, we do get a good chunk of grants coming from various city, state, and county-based funders, and from a few arts funders, like the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts. We also do a fundraiser pretty much every year, and do solicitations for individual donations. So I would say that maybe 40% of our budget comes through earned income and donations, and then the rest is through grants.

Overall, what have you learned about funding arts-and-culture projects? Are there any big takeaways in terms of how to make them sustainable?

My advice is to try to diversify where your money is coming from, so if year to year those things are shifting, you’re not left out in the cold.

People often think you need to know a ton of rich people to make things like WCCW happen, but that wasn’t the case for us. It can be grassroots. You can get a little bit from a lot of people and it’s not necessarily easier, but you can make it work that way. For us, relying on membership fees really helps make us accountable to the community we’re serving. So it’s a nice way to have it be.

I would also just say, it takes time. I think people are like, “Oh, it’s not working,” because six months in, they haven’t been able to generate the income they’re hoping for. But it can take years, especially for grant processes. You’re often applying a year out for something, and then you won’t get the funds for another three months after you find out whether you got it. So you really have to be thinking and planning far ahead. You can’t be super reactive in that way, which, depending on what you’re trying to do, can be challenging.

It’s hard because it feels very chicken-and-egg, like you need to have the demonstrated impact and the track record to get the grants, but you can’t really do that until you have funds.

Yes, yes. I don’t think this is how it should be necessarily, but I think the reality often is that you have to prove you can do it with no money, to get some money for it.

That’s good advice. Do it with no money first, and then it will be easy once you have the money.

If you have an idea for this kind of thing, do sample versions of it. Do a small-scale version. Do a one-day event. Try to do a small residency version of it. Do it in these sort of micro chunks that aren’t going to break the bank, but that can create examples of your idea that you can then use to apply for funding.

I think people think that if they have great ideas, then they should be able to get those great ideas funded. And in a perfect world, they should, but to be more realistic, you often have to have some concrete examples of you doing the thing you’re trying to do.

Can you talk a little bit about the challenges of growing WCCW over the past six years? Is the goal to keep getting bigger?

We’re really invested in thinking about, “How can you have a feminist cooperative structure while running a sustainable business?” We’re definitely not of the mindset that bigger is always better. We are in a 2,500-square-foot space right now that constantly feels like it’s at capacity, or like there’s demand for more space. We don’t want to necessarily jump to a 15,000-square-foot space. It’s not even that we’re actively trying to grow—scaling up is really about us trying to meet demand.

Sometimes it also feels like we are at capacity, in terms of the funding we can get. We are getting a lot of the funding that, for our size, we’re eligible for. Then, there’s this big jump [in operating budget] before a lot of the big foundations will step in and help out. The question of how you get from our size to maybe [an operating budget of] a million dollars, or a million and a half, is challenging. Especially as we’re looking into moving into a new building, and thinking about how to scale up staff wise—how can that funding work out? That’s a game we’re figuring out right now, a little bit as we go.

When you were talking just now, you referred to running WCCW as running a business. I think generally, there’s a tentativeness around talking about artist-led projects and institutions as businesses. So there’s an interesting tension when you are trying to do something that’s kind of anticapitalist at its core, but you’re still working under capitalism. Have you had any learning experiences that taught you how to navigate this tension?

Navigating that tension is a constant struggle. Obviously, we’re a nonprofit, so making money is not our primary goal. But we have to consider how to pay our staff fair wages so that they can afford to live, and how to pay artists well for their projects so that they can afford to continue to be artists in this city. As a nonprofit, you do need to make some money and you need to spend some money. So you’re trying to balance that out every year. Thinking of it like that can be helpful—the idea that everyone benefits from us making money. It’s not just like me or somebody else is getting a check at the end of the day if we turn a profit. Anything we make goes right back into the organization and into our projects and mission.

As a first-time executive director, what have you learned about leading a nonprofit?

For me, personally, one of the biggest challenges of stepping into a leadership role has been learning to operate both as a public-facing person and public-facing organization, that people are looking towards, both in good and challenging ways. People are looking to us and want to know how we’re doing it and want examples and want advice and insight. We’re not just by ourselves toiling away in a little corner. Instead, we have the challenge of being leaders in this field, trying to be very adherent to our values and very clear about what those values are, and operating in a really kind of a radical way, and being very clear about what that is. I think that’s been exciting to people. But the attention of that is sometimes a little personally challenging for me. I’m more of a behind-the-scenes, numbers-and-spreadsheets person. That’s the kind of stuff I like. But I’m having to own that people are looking to us—and that is great, but challenging.

As an executive director, have you felt pressure between what you personally think should be done, and then what other people outside are pressuring you to do?

Not often. I mean, we have a great board that’s really supportive of the staff. I think that’s often where nonprofits have challenges—when the board has very different ideas about what they think should be happening. That was one of the biggest warnings when we were starting a nonprofit—that people had really challenging relationships with their boards. But we’ve had an excellent experience with that.

To go back to funding, I think you can get into these positions where sometimes, early on especially, when you need money, you’re often chasing opportunities. It becomes tempting to make something that kind of fits into a funding opportunity, and then let that shape what you’re doing, even if it’s kind of a compromise. In the beginning, you can find yourself in more of those types of situations. But right now as we’re growing, we’re really trying to shift our focus to our actual vision, like, “In an ideal world, what would we want to be doing? What feels most urgent right now? How can we seek out the funding and find the right opportunities to support that, rather than the other way around?” It’s been a good learning curve.

As you’re considering what you really want to focus on, how are you factoring in the WCCW community’s needs against your own instincts and priorities?

From the get go, we didn’t want WCCW to be like an exhibition space that’s open, that hardly anyone is at most of the time. We wanted it to be an active space that was useful for our members, and we thought a lot about what that would look like. We have a co-working space, so members can come in and use the workspace Monday through Friday. We also host events usually multiple times a week, and with all that going on, we have these very active feedback opportunities. So we’re constantly getting feedback about what’s working, and what topics and themes are feeling most important, so we can continuously be listening and adjusting.

Also, for almost all of our platforms—like our events, our artist in residence program, and Co-Co press—we simultaneously take proposals for all of those things from anyone who has an idea. I think that helps us keep aware of what people are wanting to talk about.

I also think the whole staff helps us stay in touch with the WCCW community. I’m in touch with other executive directors or people running organizations. The programming director is very up on what’s happening with other organization’s programming. Our associate director is talking to our members all the time, and knows what’s going on with them. I think it’s just about everyone considering their outreach responsibilities within their roles, and making that a very important part of their job.

It’s like you’re giving yourself a leg up by having everyone be really open to the community in a transparent way. Does this way of working ever feel too hard, because you’re just navigating too many people’s ideas and input?

Of course, people have ideas all the time that would be great, but there’s no budget, or not enough time. But we try to hold those things. That’s a challenge as well. You try to hold those things and be responsive while at the same time being able to clearly relay what the realities are.

We have a quote that we love: “It’s always easier to oppose than to propose.” We got it from this other great LA organization Clockshop, who did an extensive Octavia Butler project. That’s something that we hold. If you feel like something’s not happening the right way, then what is your proposal for how it should be happening? It feels important to ask that question alongside any sort of criticism. But generally, people have good ideas. We’ve learned that we don’t know everything, and there are lots of creative ideas for how to solve problems.

What are you excited about tackling next for WCCW? Are there any experiments, or new programs or ventures that you’re really looking forward to?

Yeah. We’re in kind of a funny growth moment. Our lease [for our current space] is up in March. Now, we have a little better sense of what the organization wants and needs in terms of a physical space. So since we’ve outgrown our current home, we’re looking for spaces that fit our needs more squarely. My hope is that in the next few months, we’ll be moving into a new location.

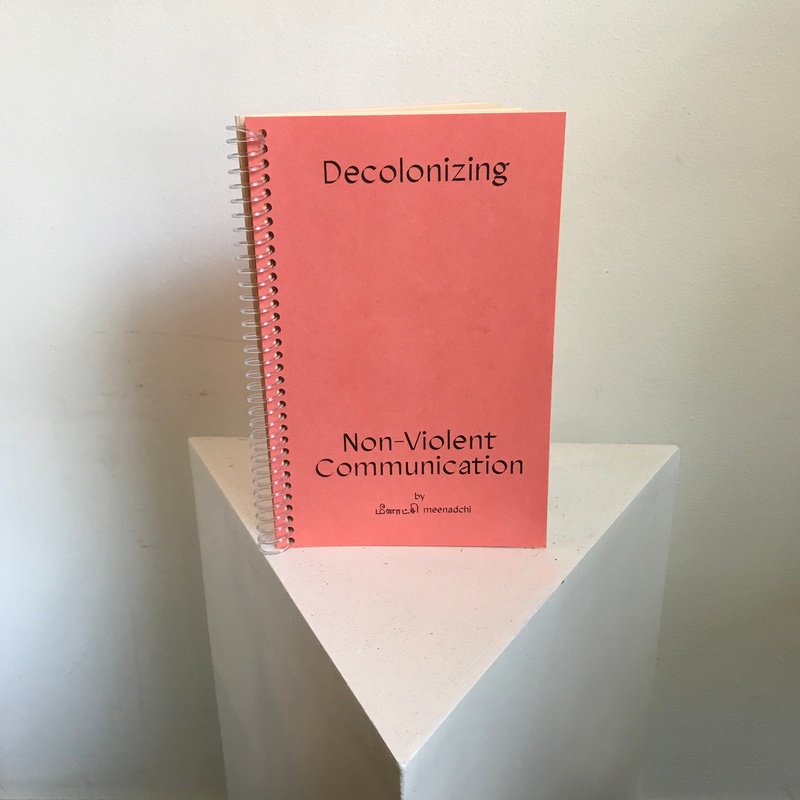

Something else I’m excited about is Co-Conspirator Press, which we launched this year, sort of as an experiment. Our first book was Decolonizing Nonviolent Communication, and right now we’re in our fourth reprinting of it. I think we’ve sold almost 2,000 copies since April, which is wild. I’m hoping in the next year we’re going to translate it into Spanish. We also have a number of other books coming out on the press that we’re really excited about. One is by Sarah Lyons, who teaches our basic auto care classes. She wrote a car manual that’s amazing.

How have you been distributing Co-Co press’ books? Obviously doing independent publishing is a little tricky. It’s hard to get the word out and get people to buy your books, unless you’re partnering with a big publisher and getting help with distribution. How has that worked for you?

Well, we have this incredibly interested audience. Our programs are very LA-focused, but we also have a lot of people who are watching from elsewhere, who want to participate—and we haven’t had a ton of opportunities for them to be involved until this year. At this point, 90% of the sales we’re doing ourselves, just through our own channels, like Instagram, Facebook, and our newsletter. Then we are also wholesaling when people approach us. We did a little bit of outreach around that, but I would say it’s about 90% our own sales and then 10% wholesaling right now.

We also do fairs. We’re going to do LA Art Book Fair and Frieze in LA. Fairs are also good opportunities to meet new people who maybe haven’t interacted with us yet.

With so much going on, and so many responsibilities, how do you avoid burning out?

I don’t know how great I am at that. I try to delegate, and this is something that was much harder early on, but I’ve realized that I don’t need to handle everything by myself. We have lots of capable people on staff, who are excited and wanting to handle different things. Also, I try to be really good about email time. I try to only do it when I’m here in the office. Of course, there are things that come up, but I generally try to avoid feeling like I need to be on my phone or email at all times. Even if I look at it, I try to be really thoughtful. If I have that impulse to respond, I ask, “Do I actually need to respond to this right now? No, this can wait until tomorrow morning, when I’m back at my desk. It’s fine.”

“There are no art emergencies.” That’s also my line. But, then sometimes people can’t get into the building and that is actually more of an urgent issue.

For my last question, I always like to ask: if you could teleport back to five or 10 years ago, as you were trying to get this space off the ground, what foundational advice would you like to give yourself?

Getting a space off the ground is all about relationship building. You cannot do it yourself. It’s like, actually impossible. You must build and maintain good relationships with people you’re working with, whether it’s with people who are becoming members, or with vendors, or with whoever else might be part of the big picture of making this all happen. You have to take great care in those relationships. Sometimes it doesn’t feel like the most important thing, and you’re firing off emails quickly that sound curt because you’re just stressed and trying to get things done. But it is crucial, and really the most important thing, that you build these relationship blocks as you’re doing it. That’s what’s going to allow things to happen. We can do so much more together than we can individually. That’s what’s going to keep people wanting to stay involved, and wanting to help make this thing happen.

Sarah Williams recommends:

-

Baker Creek Heirloom Seeds, sign up to get the Whole Seed Catalogue

-

Eaton Canyon hike in LA

- Name

- Sarah Williams

- Vocation

- Executive Director, Curator

Some Things

Pagination