On how we can all create an individual encyclopedia

Installation artist Stephen Talasnik discusses the distinction between finished and complete works, the lack of training required to be an artist, and the subconscious impact of memory.From what I understand, you began working in sculpture well after you first delved into art via drawing. How did you know you were ready to try pursuing a new artistic discipline?

I had actually started with sculpture before drawing, but that was at about seven or eight years old. I went back and dabbled with sculpture a bit after my graduate work, so there was a gap there of about 20 years. I always knew that drawing was going to take me to sculpture. I just felt it. Except that I never knew what it was going to look like, and I didn’t know what it was going to be made of.

I had the opportunity to spend time in the Far East in the late ‘80s and travel while using Tokyo as sort of a gateway to that area. I became seduced by the use of bamboo poles for scaffolding. And scaffolding would inform what I would do as sculpture.

I recognized that scaffolding was compelling to me because of the experience I had when I was seven and eight years old. I used to build things like roller coasters out of toothpicks. It was always linear, and it was always pole-like. It wasn’t until I started traveling that I started to think about what I might do as sculpture. It took another 15 years after the time I was introduced to Indigenous construction in the Pacific Rim—I spent time in Thailand, the Philippines, and China as well—until I developed the vocabulary and interest in a material that I thought I would be comfortable with if I were to ever make sculpture.

I started making sculpture at about 45. There was a considerable gap between graduate school and that time. I chose wood because it was the easiest material and it was accessible to me, but the wooden stick was very much in line with the whole notion of the bamboo pole, the difference being that bamboo is flexible.

The experience of drawing over the years lent itself to the idea of linear construction. My early pieces were based on the creation of space frames, through which, when assembled, one can create larger structures. The classic example is the construction of a blimp, where the blimp is not built as one large structure. It’s built in slices, like a loaf of bread, assembled to create a larger shape. That was how I was building in the beginning.

Around my late 40s, I started doing small-scale sculptures like that. Eventually, it led me to create my first large-scale piece at the Storm King Art Center in 2008, 2009. I had the opportunity to use bamboo poles for construction. I used them because it was an outdoor piece and it had to be large, durable, and temporary. This was a piece that was supposed to last for two years, which it did. That all came out of drawing. If it were not for drawing, there would be no sculpture.

Anatomy of a Glacier, Photo: Jeffrey Scott French

What role did skill-building play in your ability to start sculpting in your mid-40s?

The simple answer to that isn’t that I reject skill-building, but that I’m not a woodworker or a cabinetmaker. I selected wood purposefully because it was simple to use. It didn’t require a lot of skill to build the types of things I was building. I didn’t want to use hand tools, and I didn’t want to learn the traditional art of cabinetry or Japanese joinery. For me, using sticks and simple materials like a glue gun and wire cutters to cut the wood made the structures more gestural, meaning it went back to the type of drawing I was doing. It was void of accuracy through measurement.

One of the endearing labels my work has fallen into is fictional engineering. That term has been used to describe a structure that possesses all the language and qualities of traditional engineering but isn’t based on a numerical system or any exactitude. I don’t use computer software to build my structures, even though they possess some of the linear characteristics of a drawing you might see on [computer] software.

By keeping it gestural, meaning the absence of measurement but also the sense of the hand, I was able to preserve a degree of intimacy and parallel some of the activities I was continuing to do in drawing so that there were no traditional wood skills involved. It was a passion for building things and making things, but really, building things by hand and wanting to build them fast but intricate. That was consistent, at least parallel, sometimes intersecting, with drawing.

I had no formal education in sculpture or how to use certain types of tools. I was introduced to the tools when I was a kid. My dad used to be a weekend carpenter. I have a complete set of power tools that he gave to me that I never used because I had no need for it. One of the things I learned watching people build in environments where there was a necessity to build things for function, like a boat, a house, or a bridge, was that it had to be intimate, relatively quick, and void of the use of anything electrical.

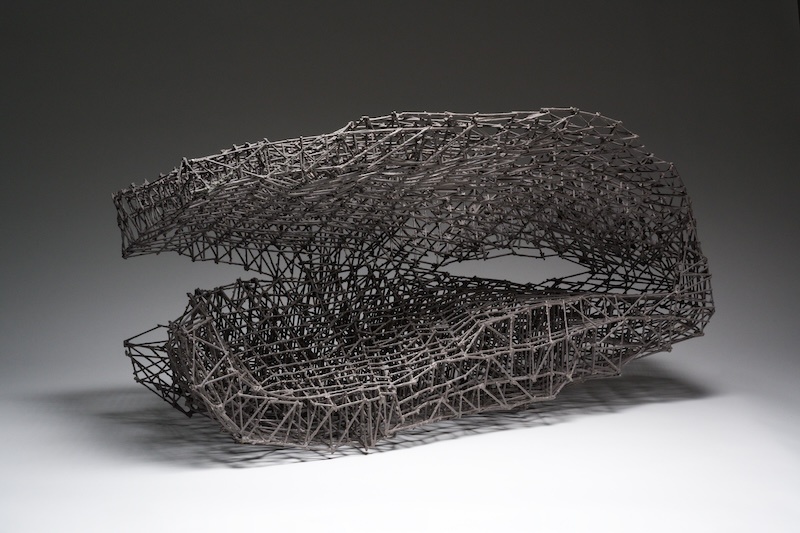

Fissure, Photo: Jeffrey Scott French

How does your lack of measurement and use of rudimentary tools tie into the notion that the less you plan for something, the freer your expression becomes?

There is a connection. I generally start with a point and rely on the simple premise in engineering that if you can create enough triangles, you can create a structure. There are no presentation drawings that most people would be doing or preliminary drawings that lead to other drawings. There’s no finite drawing that indicates what it’s going to look like. That’s to the frustration of a lot of people I’ve worked with, especially curators and directors of art centers who say to me, “What’s it going to look like?” I try to explain to them and do rudimentary sketches on an iPhone, but for the most part, I always build a model that serves as the drawing. And then, I essentially eliminate the model because what I do with the model is then absorbed into my way of thinking so that we build from scratch again, but we’re trying to encapsulate the spirit of the original model.

I have no formal training in anything I do, for the most part. I did study drawing when I was in college, but it was a very formal approach to drawing. It was when conceptual art was becoming a formal part of an art education. I had to teach myself how to draw what I wanted to draw.

The greatest learning experience for me was when I went to graduate school in Rome and I sat there copying figurative statuary and classical Italian architecture. It’s not that there’s a rejection of the educated eye. It’s that there’s a desire to not want to listen to instruction and to be as controlling as possible over the materials.

The official bio on your website says: “There is no desire to finish, rather an ambition to complete.” What distinguishes finishing and completing something for you? Put another way, how do you know when one of your works is done?

The quote of “unfinished, but complete” was first introduced to my lexicon when I was studying the drawings of Michelangelo. I read about his work, and one of the art historians of the time said his drawings were purposefully left unfinished, but there was a sense of completeness to them. That was the philosophy I used as my religion, which was to create something that appeared unfinished but had a spiritual completeness to it.

My sense was that, by leaving something unfinished yet determining that there was a sense of completeness to it, I would seduce the viewer into the act of creating their own finish. Every artist desires to bring the viewer into their work. This was the means through which I was able to do that.

I learned from looking at the Michelangelo drawings and, in particular [in] The Slaves—which, to me, are some of the greatest works of sculpture ever—there is a sense of these figures being part of a block of stone and that they’re unfinished purposefully. But the idea, or at least the feeling, is that there’s a sense of completeness, and part of that completeness is consciously there as a means to seduce the viewer into the act of creation. That, to me, is one of the higher forms of art-making. Not to say it’s a rule or a formula, but it’s an ambition [that] by being overly finished, to me, it distanced the piece of art from the viewer. I don’t like concluding an idea through finishing it. I like the fact that it’s unfinished, because the unfinished inspires or informs the next piece that follows.

I generally work in a series or a sequence, whether it’s drawing or sculpture. All of these are not done one at a time. There’s no beginning, middle, and end. There’s just a beginning and a middle. There might be a beginning and a middle on seven or 10 works in drawing or three works of sculpture. These pieces work off each other so that they more or less become complete around the same time. Overly working them, to me, takes the life out of it. It prevents the piece from breathing. For me, drawing and sculpture are most seductive when they have the capacity to breathe with the viewer so that there’s the triangulation of the artist, the object, and the viewer. I have a responsibility to enable this piece of art, two or three-dimensional, to breathe, and to enable it to breathe with an audience. It’s like an unresolved mystery.

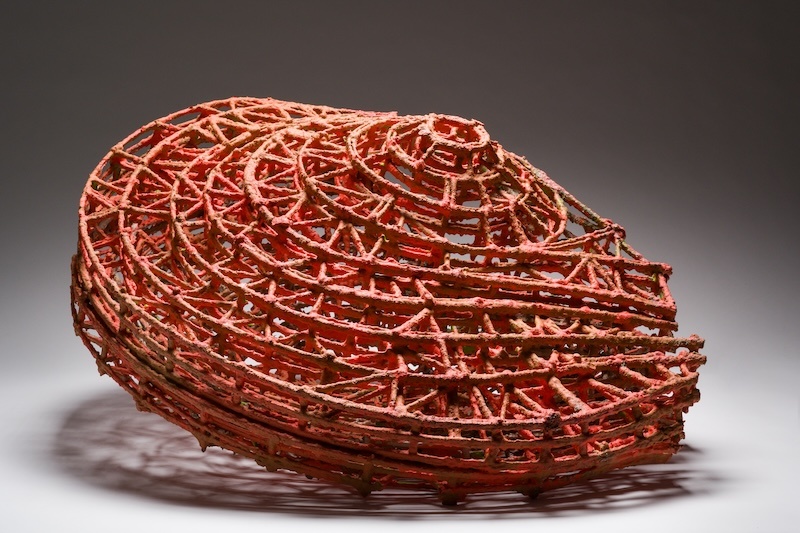

Leaning Globe, Photo: Jeffrey Scott French

I believe you built your piece FLOE on-site at The Museum for Art in Wood. How does where you’re creating your work influence what you do? Is there anything you look for, whether in a studio or at a museum where you’re building an on-site installation?

There’s usually an initial visit to a proposed site, and usually, the site speaks to the scale of the work. In the case of FLOE, the rectilinear part was constructed off-site for expediency. But for the most part, I usually do that on-site, but it takes much longer. The beauty of FLOE was that there was a very limited period to do it, so a lot of it had to be done off-site and then brought in. What can be done off-site is the infrastructure, and you can add and subtract to infrastructure, but you can’t add and subtract in the same way to the skin, which, in the case of FLOE, is the flat reed bamboo.

That skin, you can’t predetermine what it’s going to look like. You can’t do a final presentation drawing. You can only rely on the infrastructure to inform how that skin is going to fall. You can manipulate it if you so choose, but you need to have connections to the infrastructure. You can’t really envision what the skin is going to look like, and that’s the true leap of faith applying a skin [when] you have no idea how it’s going to conform to the infrastructure you build.

There are variations in the infrastructure on purpose. One of the more seductive qualities of building is creating variable repetition. It guarantees that when all these flat frames are assembled, you’re going to have different sizes but that, ultimately, the core is all the same. However, you can manipulate the exterior because you know the infrastructure is relatively consistent and sturdy.

FLOE: A Climate of Risk Glacier installation, Photo John Carlano

I’m also curious about how where you’re living and working, not just the art space within that, affects your creative process.

I’ve lived most of my life in major cities and spent chunks of time in some amazing cities that I would like to have spent more time in, like Berlin or London. The infrastructure of cities has always informed my work. That goes back as far as living in Philadelphia. I was able to travel on the Schuylkill Expressway when it was relatively new. I saw the construction of the twin bridges that cross the Schuylkill. Also, Franklin Field on the [UPenn campus] wasn’t far from where I grew up.

I lived not far from the Atlantic Richfield oil refinery, so I saw the construction of these massive oil tankers. I lived not far from the Navy shipyard at a time when they were building ships. I went to [the former] Connie Mack Stadium for the first time to watch my first baseball game. These were places that created moments that [informed my] work for the rest of my life. That’s why I valued the opportunity to have grown up in a city. Not to suggest it would be the only place where one could grow up and be informed by what surrounds them, but I consider architecture rooted in engineering to be my nature.

We all have the capacity to create an individual encyclopedia, which is a collection of moments throughout our entire life. Most of the moments invested into this encyclopedia, we’re not even conscious of how they might play out in the end. But every once in a while, these moments manifest themselves in different ways. In my case, it’s a matter of taking an idea and dragging it through that encyclopedia of moments. You create, at the end, a new nature, which is somehow more natural than nature itself. Not to suggest that there’s something greater than nature, but that nature is a part of it, that we add our personal experience to find something new and hopefully inventive relying on the imagination as well.

That encyclopedia goes back to your childhood. That’s what I like about referring to it as an encyclopedia. It’s not just a collection of events. There’s a certain degree of chronology, like an alphabet. You’re making things that are a result of moments that are either conscious or unconscious. They can be moments that engage more of the senses than just the visual. Any of those experiences I described, whether Connie Mack Stadium or Franklin Field, were not only moments that I experienced. There were smells and sounds. All of these elements influence the work.

Stephen Talasnik recommends:

Five entries in an expanded Personal Encyclopedia of Moments:

Create an opportunity to live in a different country. Not as a tourist, but a residency for at least 6-10 weeks or one or two years. Find one of three different situations; a Western or European metropolitan area; a place in the Far East; and a Wild Card location where the people live without modern conveniences; i.e. “the third world”. Learn to re-evaluate your own culture by examining the traditions and values of others. Try to befriend natives and listen to their stories. Don’t illustrate your experiences. File them away and they will organically make themselves known at the right time.

Collect artifacts from your travels: Find small objects or documents from your experiences that encapsulate the memory of experience. Use them to “recharge the battery”; to trigger events through the senses other than sight. Rely on their sense of smell, sound, or touch. They serve as time travel, reminding you of the past; a collection of personal fossils that have meaning only to you. Keep them small enough so they don’t become a burden to store or carry. Return to them every so often as a reminder of your journey. They document a moment, seize the senses, and are more uniquely honest and personal than pure photography. Each object should tell a story.

Surround yourself with creative people not in the visual arts: Learn what you can about creative processes that are not directly similar in process or product to yours but still thrive on a creative impulse; architects, writers, musicians, dancers, etc. People who express ideas and go through a variety of problem solving that is both subjective and objective. See creativity through their perspectives. Have them look at your work and get their responses; not as critique, but as means to hear how their given professional means of problem solving is both consistent and different from your studio practice.

Surround yourself with people that represent disciplines that are void of creative expression and problem solving: As you evolve as a studio artist, never stop learning from the experiences of others; doctors, scientists, athletes, mathematicians, lawyers, blue collar workers; anyone that is conversant about what they do and why they do it. Why did they choose what they do or their passions?

Be a “twig in a stream”: Allow yourself the luxury and insight, not to over plan your journey. Allow the current to take you in different directions. Know that you will get attached to obstacles along the way but know that you will also be released and can move on. Learn from every opportunity and when it is a safe place for connection versus falling victim to the hazards of over attachment. Let the current take you without fear of your next movement but don’t over plan your timeline. Allow for spontaneity. Take your time and enjoy the journey, grow at your own pace.