On having faith in yourself and your abilities

Prelude

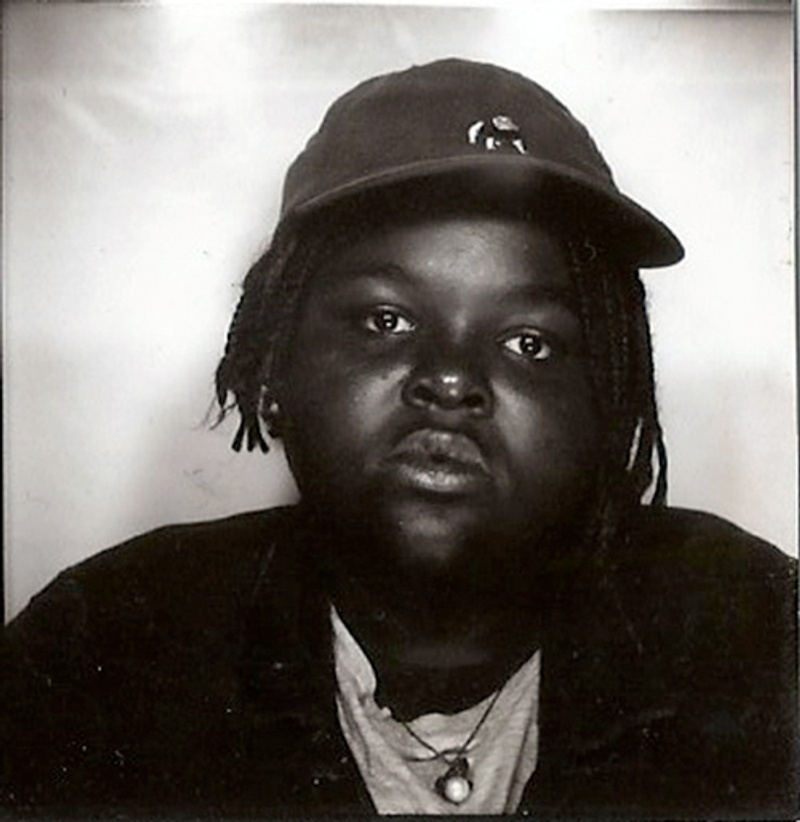

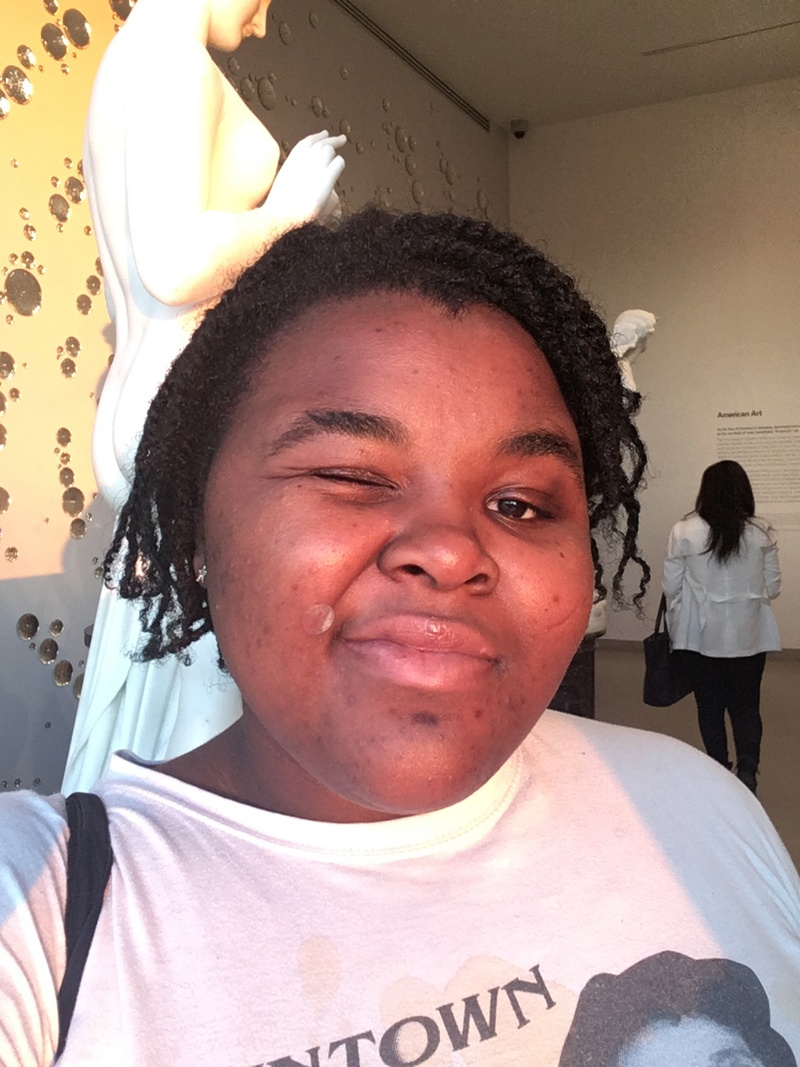

No Home is the solo music project of London-based multidisciplinary artist Charlie Valentine. They are also a photographer, graphic designer, and writer of the music zine Hungry and Undervalued. Their first full-length album, Fucking Hell, was self-released in June.

Conversation

On having faith in yourself and your abilities

Multidisciplinary artist Charlie Valentine on taking your time, being brave, finding joy in the everyday, debt and day jobs, and the inspirations behind their project No Home.

As told to Jenn Pelly, 3233 words.

Tags: Music, Art, Design, Independence, Beginnings, Multi-tasking, Identity, Money, Inspiration.

We met a few years ago at a Priests/Downtown Boys/Big Joanie show in London, where you were born and raised. What was your introduction to underground music there?

As a teenager I was into pop-punk, looking at who was on Warped Tour, and then I was like, “Okay, this is not for me.” And I pivoted. I was searching for Black rock stars. People who made music who looked like me. I was just incessantly Googling “Black people in rock,” “people of color in rock music today,” and then “DIY,” “DIY London,” trying to understand, as a 19 year old, “Where are the DIY spaces?” which is hard if you don’t have someone to bring you into those spaces.

One of the first artists I was super interested in who came from independent music was Mitski. I went to her first London show in 2015 and ended up having a really amazing experience. In a way that show changed my life because I had never seen so many young people of color at a show ever. I remember thinking, “Holy shit. Something is changing.” I remember walking to the train station afterwards, like, “Wow. I really got to change my life.” I remember the crispest air. I remember feeling so spiritually full but also drained, like, “I’m alive.” I went home and thought, “Maybe I can write songs.” I had spent so much time thinking about the mystery of making music, but watching other people of color play music was demystifying it in a way. And there were some other things—some resources I found on the internet.

What resources?

Back when Grimes was super active on Tumblr, she wrote this master post of what you actually need to make a home studio. It’s important to sometimes break it down for people, not in a condescending way, but like: “This is what I use. I use this audio interface. You don’t have to use an expensive version of these things.” Even now, I’ll ask: “Okay, it sounds boring, but what are you using?” And to this day, all the audio stuff I use, I bought because Grimes mentioned it in a Tumblr post that is now deleted and that no one can ever find. [laughs] But I know it existed.

How old were you when you started playing music?

I have been singing from age four at church and my first instrument was the violin when I was five. Then I got to being a teenager in school and I would get so embarrassed. I had a really good voice and I wanted to join the school choir, but I was shy. People in the choir at school would treat art like a competition and it intimidated me. I stopped playing music for years. But one of the first things I understood when I became an adult is that art isn’t a competition. Everyone makes things in different ways, and artists’ goals can be different. When you learn an instrument, you have to understand that being bad at something means that one day you’re going to be sort of good.

The first No Home EP you put on Bandcamp in 2016 had a note that read, “This EP is about destroying yourself.” What did it mean to you to say that at the beginning of this project?

I was trying to begin anew. I was trying to express something. My life was also way different then: I was in university, I was working in a supermarket, I would be doing hard shifts, and so much of my mental capacity was just thinking, “Am I going to get fired?” It’s very difficult to control your life if you work a hard retail job, where there are rules and regulations and you have to wear something specific, and your manager doesn’t let you take time off, and then you go home and try to do uni work. Those were just some of the harder times in my life. I still had really no money. But I had a need to have little pockets of joy. I remember if there was nothing to do on shop floor, I’d pull out some till roll and write lyrics or a to-do list of things to do when I got home, so that: When this shift is done, I’m out of there. I’m mentally and physically out.

Your album Fucking Hell is in conversation with the world—your lyrics speak to the economic realities of being an artist, to living with student debt—but it also feels like a self-contained universe. How would you describe the world of this album?

A lot of my older work is bubbling, bubbling anger. But now I think I’m making fun of myself. Some of it is fiction, which I’ve actually written a lot of in my life. I used to write novels—I would participate in NaNoWriMo and write 50K words a month. It gave me a great foundation for understanding how deep can you go telling a story: Can you understand, within four minutes, that this is about a person who’s fallen from grace, resigned to their position in society? Can you understand that they’re really excellent at their job, but overlooked, and also hated by a lot of people? I’m not a person who’s deeply into love songs, but I’m deeply into songs that tell a story. Fucking Hell is like a concept album, asking: What if I was the devil and I wanted to no longer live in hell, no longer live in exile? And I wanted to feel love, and to just be a normal person?

I tried to run a spiritual, church-like experience through the album. It appeals to the senses. It had been done for two years when I released it on Bandcamp in June. I wanted to find a label to release it but never did. Then I thought, “I’m a bit bored of having this part of my life sitting on a hard drive. I could creatively move on.” After the resurgence of Black Lives Matter, I also felt like, “This album is really helping me at the moment. Maybe it could be helpful to other people.”

(Fucking Hell album art)

On “I Couldn’t Cry Before I Wrote EPs” you sing about how “modern life is overwhelming” and “tweeting into the void/the fast thrill/of being humanoid.” What made you want to narrate that?

Blur.

The band?

Yeah, Blur and Pulp. I spent hours watching BBC documentaries about rock bands from the 90s—which was a completely different music industry, a different era of Britain, a different world. It’s interesting to see how those bands were treated and what kind of commentary they were trying to make on class and British society. A few days ago, I saw a tweet where this guy said, “from the ’60s to the ’90s the UK had three amazing funding schemes for young artists and musicians. The dole, student grants, and no university fees.” It’s just so much harder to be an artist today. It’s way harder than it should be, for no reason.

So much of Fucking Hell seems attuned to the economic realities of its own existence—like a form of cultural critique. On “Drink You’re One of Us” you sing “I got debt nipping at my heels/But no one cares how it feels.” What did you want to evoke? Student debt can dictate so much of what you’re able to do as an artist.

Yeah, 100%. I’m just saying the truth. I’m going to give you honesty. I didn’t want to lie and be like “Everything is fine, you get out and you get a job.” It’s monetary debt, and then also “How much do I have to pay until I can do what I want with my life?” debt. I hate a culture of, “No no, if you have debt, you must not talk about it. If you’re suffering, don’t talk about it—it’s too much.” It’s real life. We can talk about it and we can laugh about it.

But it’s difficult—the album has been gazed upon in a very white way. That’s the gaze that it’s seen through on the popular music sites. Rock music is perceived to be a white genre; there aren’t many prevalent Black critics of color in the UK, and there aren’t that many Black rockstars. It makes you conscious of your audience and your art if the people who interact with it are white men, like, “What’s going on here?” So would people ever understand, from a Black British perspective, that Fucking Hell is a dark comedy? That’s something the UK actually does very well, but that Black women here don’t really get to do on screen and on TV and albums. I think Fucking Hell is a funny album, but it’s also deeply sad.

A lot of the lyrics are both funny and sad, like on “I Couldn’t Cry Before I Wrote EPs” when you sing “Therapy’s too expensive/So I’ll have to sing along.”

Or when I sing “You could play me for free or £5.99 a month” on “4x4.” To put your music onto a streaming site, you pay what, £30 a year? And if you don’t have that money, if you just put out your Bandcamp release, do you exist to the rest of the industry? Do you exist to Instagram? Is that a legitimate album to the music industry?

When I started making the album, I was still in uni, and when I finished it, I was six months into post-grad life, and it was horrible. I was thinking to myself, “I have accomplished things in my life. Why can’t I get a job?” It was very difficult for me to understand, so I satirized it. I made a piece of satire art.

Now I have a day job working for an American clothes company, and my co-workers and I get paid £21,000 per annum, which comes out to roughly £1,400 a month. As a young person, that doesn’t leave a lot of room for mistakes. That doesn’t leave a lot of room to make art. That doesn’t leave a lot of room to be free.

This also reminds me of “A B- in This Economy,” where you sing about “post graduate anxiety” and the invisible labor of having to enact a persona at work. Another line goes, “Will I be proud of me/Just surviving for a 9K annual fee?” What inspired those lyrics?

It’s 9K per year to do your degree in the UK. I was studying graphic design and I just wanted to drop out. I spent a year abroad in uni, working in the quote-unquote graphic design industry for this huge sports brand. By the end, I was extremely disillusioned by it all. I came back to London and I remember thinking: Who’s going to be proud of me for surviving all of this? I’m not happy. I have to work so hard. It just felt like a hostile environment. One of the tutors on the course convinced me to stay, but after that, I was like, I don’t care what grade I get. I’m going to do it on my terms. In the end, I thought: I’m proud, but also I feel nothing.

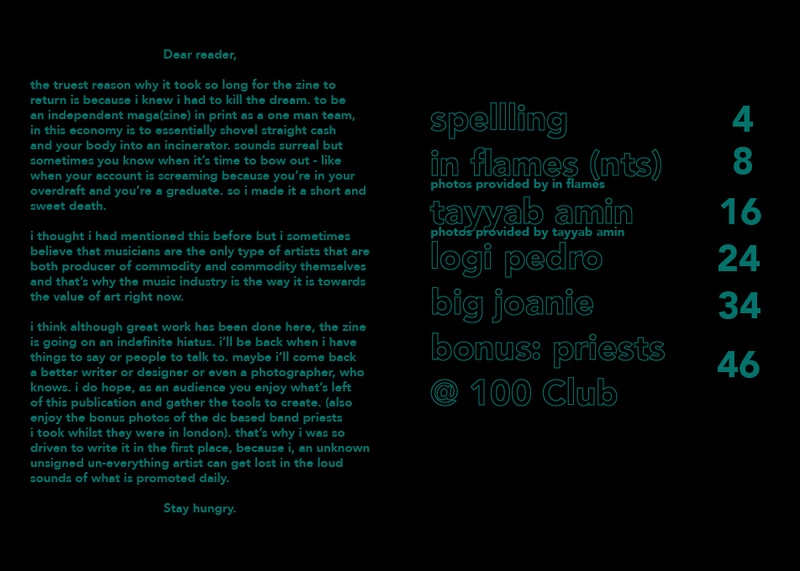

(Excerpt from Hungry and Undervalued zine)

The name No Home evokes a feeling of dislocation, but the title Fucking Hell seems really British.

No Home is just my identity: Could I ever envision a long life in the UK? Am I truly a citizen of the UK if Black people are constantly dehumanized in the media? Fucking Hell has a double meaning—I was writing an album about literal hell, and it’s also a British euphemism for a moment of annoyance like “Oh fucking hell Gary, the cat’s torn apart my uniform.”

Who is an artist that changed the way you thought about music?

When I was finishing this album, I had no day structure, so I would go for runs in my local park. My biggest, most joyous memory is discovering the Kate Bush album Hounds of Love, and hearing that whilst running is pure euphoria. I was going through it. It was winter time and it’s very much a solo woman album. It’s a woman on a mission.

You made two issues of your zine Hungry and Undervalued, interviewing artists like Spellling and Big Joanie, and I’m curious if working on it impacted your approach to music.

I did the zine because I wanted to have a better understanding of the music industry, like What information can you extract as an artist? What can you use? I was just scratching the surface, but it opened my mind a little bit. It was about trying to get people to understand that different narratives exist, like how the arts work in Iceland.

You asked practical questions in terms of figuring out how people actually exist in music today—in your interview with Big Joanie, they spoke about going to a festival in Sweden where they were paid well and fed and treated well. Reading it made me think about earlier this year when Bernie Sanders was running for president in the U.S. He talked about being an Arts President, and actually investing in culture. It seemed like practically no one in the music industry was listening to that. There are so many more high-profile musicians who could have gotten behind Bernie and they were silent.

It puts into question: What is the artist’s role in society? And then also, how do the citizens of the U.S. and the UK perceive culture? Is it a fun activity? Is it a middle-class activity? Is it arts-for-all? If it’s an arts-for-all type thing, then it’s seen differently. I don’t think the UK government values culture. If you value culture, you’ll 100% bail out the culture industries. You will dare to understand what freelancers go through. You will help them because it helps the economy and it helps other people be healthy human beings. It’s a holistic exercise for society.

Even as a person in the counterculture, I’m very concerned with how people see art work. Music is for everyone. Art is for everyone. Everyone can draw. When I hear people like my older sister say, “I can’t draw,” it’s like, “No, you can.” It’s just society has told you that you can’t draw past a certain age, or that it’s bad to be bad. It’s not bad to be bad. You have to be bad to be good.

What else have you learned from the process of being a fully independent artist in 2020?

You have to be really patient with yourself—in the process of making music, in the process of playing shows, in the process of gaining confidence, in the process of getting better. You have to believe in your pen and believe in your ability to actually play. You have to be brave. A lot of people don’t know what it’s like to be on stage alone. The last time I played live, my legs were shaking and I was just like, “How do I pivot this performance into something good?” That’s something only you can do. You’ve got to have a lot of strength within yourself.

Where do you feel your strength came from in that moment? How do you play with shaky legs?

I’m already onstage, so I have no other options. I can’t just walk off stage and be like, “I’m sorry everyone!” No way. You want to do it, you have to do it. Your legs can be shaking, but they have to shake in a good way.

A lot of stage fright comes from worrying about the audience, right? And worrying that the audience is going to see you as a fraud, or that you’re not good at guitar. But most of the time, the audience is just there to see you. If you make a mistake, it’s fine. If you find yourself up there and you’re like, “Oh my god, I forgot the words, what am I going to do?” then just repeat the verse. You can miss a chord, and everyone will be like: “Wow, experimental, jazz. Second coming of Thurston Moore!”

As the artist, you control the situation. You can turn a good performance into an amazing performance. You’ve just got to have faith in yourself and your abilities. A lot of people do not want to go up on stage. That is the difference between a performer and the audience. Being on stage is a terrifying experience. Somehow, every day pre-coronavirus, musicians were making it happen. I say all of this like it’s not difficult, but if I were to hear myself five years ago, I would have been like “What the fuck are you talking about?”

What advice would you have for someone who felt like they didn’t have the time to pursue their art?

It’s so difficult. Not only is it difficult to explain, but it’s literally difficult to do. There will be days where you’re just going to find exhaustion, where you’re going to mentally go down a road, like, “I don’t know where to turn.” You just have to keep going. You need to make space for yourself. Even if that’s just half an hour a week to do something you enjoy. Progress takes so much time. You don’t have to make the album today. Forget ageism for 10 seconds. Focus on being the best that you can be. Having at least one supportive artist friend helps, too.

But if you have that drive, you’ve got to take that drive and don’t let anyone take it away from you. You got to decide within yourself what you want for your life. If you want to be an artist, you’re an artist. There’s no, “Oh, I used to do paintings, and now I’m starting to get nervous…”—you’re an artist. Just make tiny goals. Even if that means, “Okay, in three months, I’m going to write my first song.”

That’s a great goal to have.

You just got to build it up. If you don’t know how to play any instruments, that’s fine. You can do it. Just listen to experimental music. Listen to Matmos. They’re making music out of plastic pill-bottle toys. Everything is everything.

A list of things that inspired the album Fucking Hell by No Home:

-

Unjust Malaise - Julius Eastman (2005)

-

Flowers (2017) - TV Show - dir. Will Sharpe

-

Running in the park in winter to “Hounds of Love” by Kate Bush

-

Meeting People Is Easy (1998) - Radiohead documentary

-

Man - Neneh Cherry (1996)

-

The TV show “Grand Designs”

-

Yoga once a week

- Name

- Charlie Valentine

- Vocation

- Musician, photographer, graphic designer, and writer

Some Things

Pagination