As told to Jenn Pelly, 3393 words.

Tags: Music, Art, Inspiration, Process, Beginnings, Collaboration, Multi-tasking, Independence, Identity.

On the sound of community

Musician Rachel Aggs on experiencing music as a form of communication, the value of developing your own language, and making as much creative work as you can, simply for the pleasure of doing it.What are your earliest memories of playing music?

I’ve been playing music since before memory. When I was four, my grandmother would put my hands on the piano and I would play with her, and I learned the violin when I was seven. But when I was really young it was always me and my dad playing music together. He played guitar in a folk band and I would be up way later than I was supposed to be, playing music with my dad and his friends.

And you’re in a band with your parents still. What have you learned about music from them?

My parents and I play together and occasionally we’ll go to a folk festival and do a little set. My dad got really into Appalachian music and started playing the banjo. My mom never used to play with me and my dad, but she picked up the double bass four years ago and now she’s really good at it.

My parents are both hobbyist musicians. The main thing that taught me was that music is a form of communication, and generally just a party. Most parties that my parents would have would end up in a very similar scenario of everyone jamming together. There’d be the repertoire of tunes everyone knew, certain Graham Parsons tunes or whatever—my mom was a massive hippie—and then I’d do my probably terrible fiddle solo. I was very aware that that was a fun thing to do with people from a really young age.

Trash Kit lyric illustration

All the bands you play in—Shopping, Trash Kit, Sacred Paws—have this strong feeling of togetherness to them. Does any of that come from playing folk music growing up?

I’ve been thinking about this much more as I’ve grown older. My parents’ music community is very similar to what we would call a punk scene. They operate in similar ways and people form really strong friendships. I think I was naturally drawn to that sense of community because I had a grounding in folk music.

But there’s also a similarity in the ways of making music together, which are based on listening and sharing more than being a virtuoso songwriter or soloist. It’s about creating something together and also making music that’s just for you. A lot of folk musicians, they’ll never perform on a stage, they’ll just perform in their house with their family or friends or maybe in a pub—but just in the corner. Knowing the joy you can get from playing in that way is so special. You’re in the moment, playing a tune because you want to, not to impress or entertain anyone. That’s really important to me. That is kind of at the root of everything I do.

You used the word “joy”—the first time I saw you play in 2014, I remember being shocked, thinking, “This person is smiling so wide, not standing still, emanating pure joy.” Where does that come from?

Originally it came from a place of real necessity. The music that drew me into playing electric guitar was riot grrrl and feminist punk and queercore, this music that was full of confrontation but also pride, and I needed that as a quite scrappy, shy person. I needed to create a space for myself that was empowered and strong and loud. Getting up on stage was very, very cathartic. I’ve been doing it for 10 years now, but I still feel like I need it.

When I get on stage I am proving something to myself every time. Sometimes that’s why I’m smiling—because I’m like, this is hilarious. I’m winning a battle and I’m laughing. For me, performing is always going to be wound up in issues of visibility as a marginalized person. I guess it’s coming from a place of defiance.

Trash Kit - Horizon

Your performances also feel inclusive to me, like there’s this opening for people. How did finding your own community influence what you do as a musician?

When I was coming out, I was finding out about queercore bands and riot grrrl bands, and when I met my first partner, they introduced me to the UK scene, which was extremely small. But it was a lifeline for me. I didn’t know any gay people. I can’t exaggerate that enough. I grew up in the countryside and went to boarding school. It was very, very isolated. So music was inextricable from my coming out, or just growing up. It felt very connected to this sense of identity and a community.

I was playing fiddle in a folk band with Rachel [Horwood] in 2008, but I knew as soon as it started that I wanted to play guitar in a noisy band. So we started Trash Kit. Rachel started learning drums, I was learning the guitar, and we put our music on MySpace. Andrew [who is now in Shopping] found it instantly and invited us to play at the warehouse where he lived in London. There was and still is a vibrant scene there which is very queer, and very inclusive. Andrew would put on shows for lots of people’s first bands. It felt like you could really make a mess. Our first show was crazy. We all had loads of attitude but we couldn’t play. And that was just so exciting to me. It was really linked to coming out, feeling a sense of pride. Rachel’s also mixed race, so we wrote songs about that.

I was looking at the first issue of your zine I Trust My Guitar from 2011, which was about African music, and you wrote, “Whenever I play music, I try to force myself to play the opposite of what feels obvious or normal.” Can you elaborate on that?

When I first started playing guitar, I was quite aware of the fact that it wasn’t very cool to play guitar. Even in 2009, there was a sense of, “People make music on laptops now, you know?” I really don’t care about that sort of thing anymore, but when I was 20 I was a bit worried about being relevant. I felt like, what’s the point of playing guitar if you’re going to play it like everyone else? I wanted to do something that was, if not new, at least unique. So I was quite strict with myself. I would practice guitar for hours and force myself to find my own style. Now I’m not so worried about everything.

I Trust My Guitar cover

Did you have anything in mind when you were originally trying to find your own sound?

I didn’t have a plan. I just wanted to challenge myself. It’s always fun to try and play something that’s a little bit beyond your ability. Maybe it comes back again to the defiance of performing. You’re like, “Look at me, I’m doing this really hard thing in front of people!” At the time I liked DNA, James Chance, really far-out skronky noisy guitar playing. I also really liked Marnie Stern, and I remember trying to play guitar like her, but failing. Any time I’d try and sound like someone else, I would just completely fail. But then it would be its own thing.

At that time, how did playing music relate to zine-making for you?

When I started playing guitar with Trash Kit people would say, “Oh, your guitar playing sounds a bit African,” or “it sounds like you’re from Zimbabwe.” And I would be like, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.” I then started listening to a lot of African music, purely because people had been saying that. I became fascinated with learning about different styles of guitar playing, and I wanted a structure around the stuff I was learning. Also someone gave me a copy of Shotgun Seamstress, the zine that Osa Atoe from New Bloods would do, and at the time I didn’t know any other people of color making music at all. So it was mind-blowing. That was a huge inspiration for me to make my own zine. It was like a response.

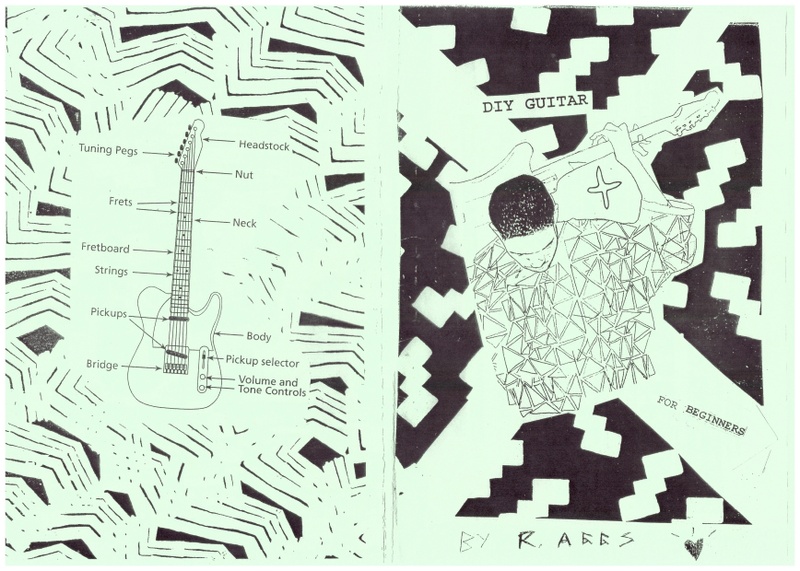

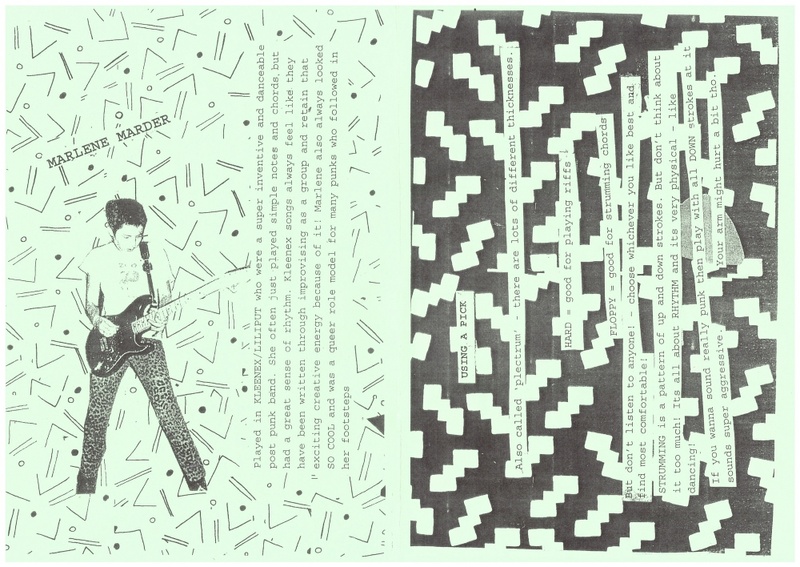

DIY Guitar for Beginners cover

You made a zine called DIY Guitar for Beginners for a workshop called “Decolonizing the Guitar” that you’ve done several times. How did that come about? What does it mean to you to decolonize the guitar?

I was asked to do a workshop for First Timers, which was a festival at DIY Space for London where everyone on the bill was playing their first gig. It was meant to encourage women, people of color, and nonbinary people to start bands. I made the zine as a handout, but I then reproduced it and started taking it to shows. And I did a workshop at Decolonize Fest, the festival for people of color.

There were no white men in the handout. It was about people of color and women guitarists. I’m really interested in what it means to be a guitarist that takes influence primarily from roots music or non-white, non-Western music, mixed in with this kind of punk or riot grrrl aesthetic. Once you remove the dominance of white-male guitar playing, it’s really exciting. It’s a good way of talking about guitar for beginners because you’re basically saying there is no wrong way of playing.

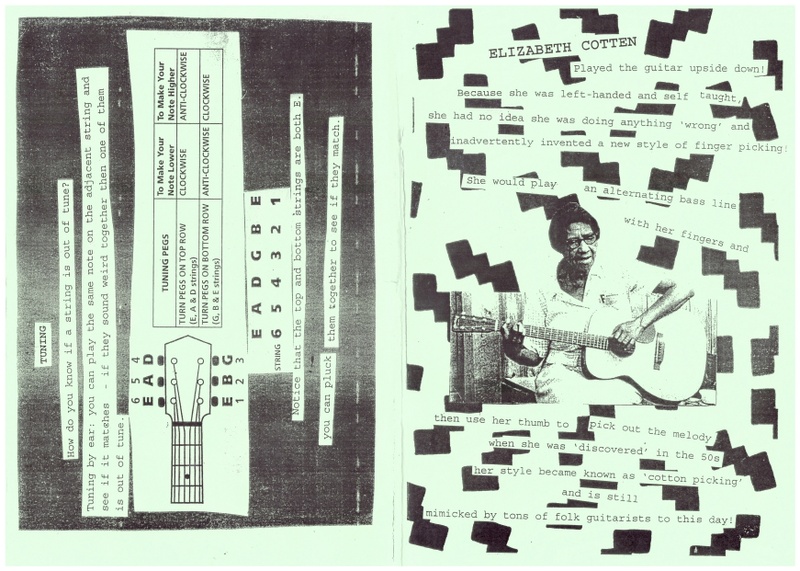

An example I have in the zine is Elizabeth Cotten. She learned to play the guitar when she was working for the Seeger family, the prominent folk family, but she picked up the guitar upside-down and learned to play what people would tell you is the “wrong” way. And in doing so she developed this style of playing that has gone on to influence tons of blues and folk musicians.

DIY Guitar for Beginners excerpt

The fact that people don’t know her story is classic in terms of the whitewashing of rock’n’roll history. These people of color and women don’t get celebrated, but it’s important to remember them. It’s really cool and empowering when you think: somebody invented a whole new style of playing by doing something wrong. But also, she invented it because she was trying to entertain herself and the kids she would look after. She wasn’t trying to wow anyone with her guitar skills. She was making music in a social way. I think that’s at the core of what it is to decolonize the guitar—to think about where it all comes from. There’s still a lot of potential in the guitar. There’s tons and tons to still be done and said and expressed through it. Maybe the white way of playing guitar is cliché, or the rock’n’roll way. But I don’t see it that way. I see that there’s lots more there.

That sense of potential makes me think of the language in your music: “horizon,” “confidence,” “strike a match,” these phrases that gesture towards possibility. Is it intentional?

It’s really for myself. It’s a sort of incantation. I need to sing things into existence, and I need to cheer myself up sometimes. I’m not very wordy.

We were talking about the feeling of togetherness in all of your bands, but at the same time, you have a very specific sound. How do you balance working collectively with maintaining your own identity?

I’ve never been particularly interested in working on my own. For me, the most exciting thing about music is collaboration and communication. There’s nothing better than the feeling of writing a song with people, and there’s a certain real, crazy joy that comes from arriving at a song, or even just part of a song, that you all instantly click in to. Something about that is so addictive to me. As soon as I started to do that with Rachel in Trash Kit, I saw the potential of doing that with other people. I’m so fascinated by how other people’s brains work. You play something, and then they’ll add something that’s so not what you were thinking, and it’s like: Wow! What? How did you…? That’s so magical. I’m not concerned with preserving my own creative voice or ego within that. I’d almost rather it wasn’t there.

Trash Kit lyric illustration

Is there anything broader you’ve learned from collaborating with people on music?

I love that bands create a sense of shared identity and a weird invented language. When you play music, there is a language in which to talk about it that is considered the “official” way of talking about music. There is music theory and there are received ideas of a time signature or a key. But I’ve never once used that language in a practice with any of my bands.

Everyone I play with comes from more of a non-musician sort of place, or even if they have had music lessons in the past, they’re playing an instrument that they are self-taught. So we don’t use that “official” language ever. It’s interesting: we still arrive at things that could be described in those terms, but just naturally. We’ll have a middle eight in a song, but nobody knows that’s what it’s called.

I think it does say a lot about accessibility, and different ways of interpreting things, and knowledge I suppose. You can have an innate musical ear, and you can also have a really good knowledge of music through just having played for a long time, without having the language in which to express that knowledge. That can be quite powerful when you think of it politically or socially. Sometimes people don’t have the language to describe even their own identity, or where they sit within society, but they have a knowledge of it because they lived it, and they have a way of communicating it.

DIY Guitar for Beginners excerpt

It’s like if you’ve spent your life absorbing music, you know something about it, even if you can’t articulate it in a prescribed language. And if you have lived life, you know something about politics, even if you can’t articulate it with an official political dialogue.

Exactly. People think they don’t know what they’re talking about because they don’t have the language, but they completely know.

This reminds me that you went to art school. Did you get anything out of that?

I did. I studied art at Oxford, and in order to get in, you had to have all the right grades and stuff, the same you would to get into the actual University of Oxford. When I was a teenager I was a bit of an overachiever. So I was like, I’ll do that! But I didn’t think about the reality of it, which was horrific. It’s just a very, very straight white place, so I didn’t exactly thrive. But I got stuff out of it. I wrote my dissertation about Glenn Branca, and when he did a “100 Guitars” performance at the Roundhouse in 2007, I played in it. I was able to read up about no wave and still be acceptable as an art student.

What was your Glenn Branca dissertation like?

My thesis was actually about composers who rebelled against the kind of fascism of the composer telling us what to do. I was really interested in composers that were introducing more of a democracy into their groups of players, and I got really into Pauline Oliveros. I was really interested in her idea of Deep Listening. Years later, I performed one of Pauline Oliveros’ pieces on two different occasions, called “To Valerie Solanas and Marilyn Monroe in Recognition of their Desperation.” It’s this very feminist piece all about meditating, and creating sound within a group, and then responding to the sound that someone else just made. And if, say, one person in the group gets too loud, the rest of the group has to rise up, and be as loud or louder. It’s this exercise in democratic listening and playing, and I found that really fascinating. I probably do a bit of that with my bands now.

I was going to ask if you had any tips for being a good listener, so bringing up Pauline Oliveros is really fitting.

Musically, her deep listening techniques are really valuable. It comes back to the music I played as a child as well. I think the majority of playing well with other people is listening. Knowing when to not play is a really important skill.

I Trust My Guitar excerpt

How do you manage being in three active bands who all tour frequently?

I just try and do as much as I can. I don’t want to give the impression that I have it all figured out because I completely do not, and I’m really tired a lot of the time. It is really difficult to keep everything balanced and not burnout totally, but I’m working on it.

If I ever meet music industry people, there’s a sort of assumption, “Oh you’re just doing this until one of your bands become successful and then you’ll quit the other ones.” And I’m just not going to do that. So maybe I make people’s lives difficult, but I refuse, because I enjoy all of them too much. I haven’t arrived at a way of doing it that fully works yet. Some days I think: yes, this is working and it’s brilliant! My life’s amazing. I’m so lucky. But there are other times where I’m like, this is total chaos. What am I doing? Probably most people who are trying to do creative stuff as a job have days where they question what they’re doing.

Do you have any artistic goals at the moment?

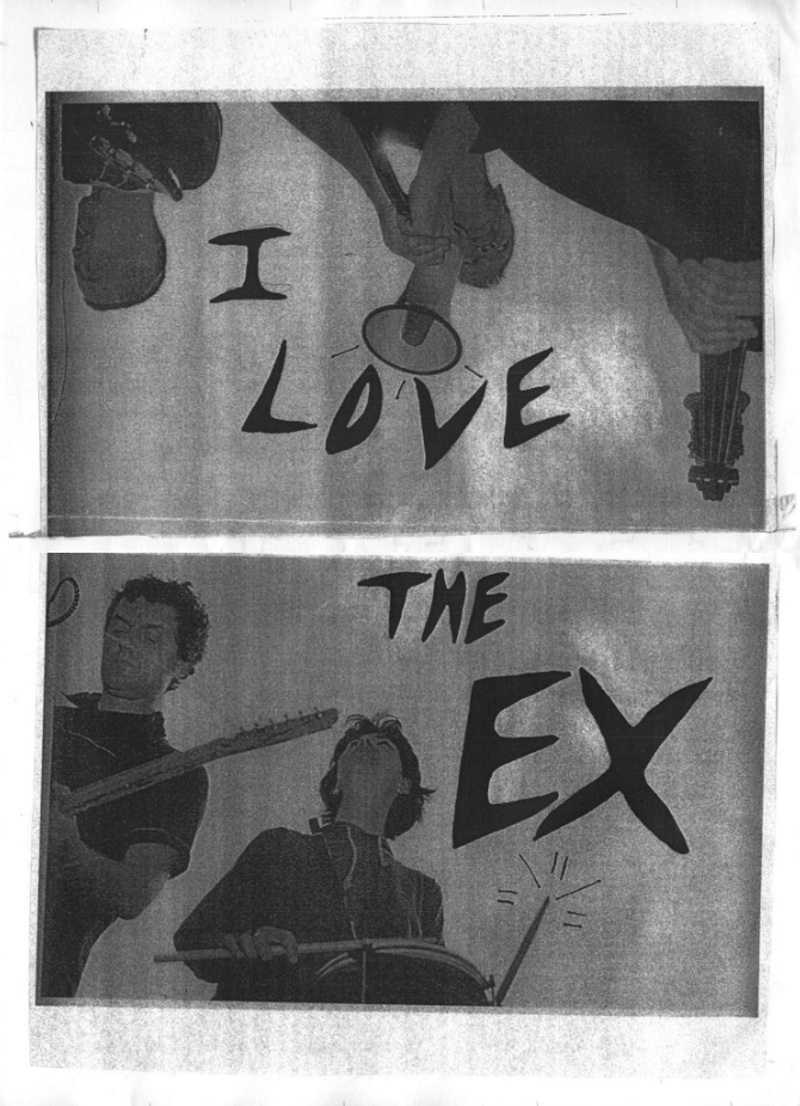

I really look up to bands like The Ex, who I get to tour with quite a lot with Trash Kit. They’ve been a band for 40 years, and they don’t play to massive crowds but they have an intense, supportive fanbase. They also have their own way of creating that’s really flexible, and they do a lot of collaboration and improvisation, which is something I aspire to.

I’ve always aspired to make a lot of stuff. I like to work hard, but I don’t like to overanalyze anything, and I would rather have made 100 weird, fun albums than one incredible album. I’m not a perfectionist in that respect. I just want to carry on making things and enjoying it.

It still blows my mind that people show up to the gigs. When I go to a town in the U.S. and 200 people show up, I’m like: Where did all these people come from? To me it’s wild. 200 people in 20 different towns is a lot of people. My ambition is to do that for as long as humanly possible.

Trash Kit lyric illustration

Rachel Aggs Recommends:

-

Charlene Darling — Saint Guidon — I can’t stop listening to this album. I love it so much! It’s really unique, intuitive music. Rachel from Trash Kit plays drums on some songs too.

-

Clear Channel — really exciting new dance punk band from DC. This is Mary from Gauche, Downtown Boys, Neonates — I love everything she does! Listen if you need to feel alive!

-

Undertale by Toby Fox — the only video game I know of that rewards you for not fighting. It’s hilarious, heart warming and the music is also genius.

-

On A Sunbeam by Tillie Walden — all her comics are beautiful but this epic, queer sci-fi graphic novel is one of the best things I’ve read in a while.

-

Mope Grooves — super special band from Portland, they play really perfect weirdo music for the soul. I got to play with them a few times recently and really treasured it.