On the emotional power of songs

Prelude

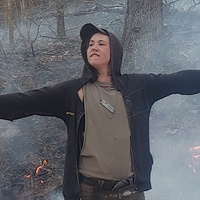

Hayden Thorpe is an English singer, songwriter, and multi-instrumentalist. From 2002 to 2018, Thorpe was the frontman of the indie pop band Wild Beasts, which he initially co-founded as a duo with guitarist Ben Little. Eventually expanding into a four-piece, the band released five studio albums on Domino Records to much critical acclaim, yet only modest commercial success. Following the band’s dissolution, Thorpe pursued a solo career, and released his debut album Diviner through Domino in May 2019. Thorpe is often noted for his distinct, operatic countertenor vocal style. Thorpe has cited Leonard Cohen, Kate Bush, and the Smiths as amongst his musical influences, as well as writer Arthur Rimbaud on his lyrics.

Conversation

On the emotional power of songs

Musician Hayden Thorpe on stepping into the role of a solo artist, existing on the fringes of what is considered acceptable masculinity, and maintaining a healthy amount of ego in your work.

As told to T. Cole Rachel, 3124 words.

Tags: Music, Inspiration, Process, Creative anxiety.

You’ve been playing in bands for a long time, since you were a teenager. Bands can obviously be complicated, but they can also provide a kind of safe space to work in. How did it feel to step outside of that and be working alone?

Raw, in truth, is the word I would use. I think anyone who’s been in a band, a band that played in a garage, or played at the local bar, or a band that plays in stadiums—what people will tell you is that it is, fundamentally, a very intimate and powerful relationship. It’s not romantic. Well, in our band it wasn’t. We didn’t have romance within the band, but certainly we had emotional intimacy. We weren’t blood related, but we were certainly a brotherhood.

Forming the band at 15 created a stasis of a lot of my emotional faculties. Because from that point on the output of my mind, I guess, was serving this greater scheme, which was our band. And when that was removed, there was certainly a sense of, “Well, if I’m not now this person to these people, then what person am I?” Frankly, I’ve come to fundamentally realize that the nature of attachment is the narrative of our lives. All the narratives we tell about, the mythology of humanity, is all about the attachment and loss of attachment, beginnings and endings. I absolutely, fundamentally believe in that. In the wake of the band ending, I just had to make something that would require a certain amount of contemplative, conscious attention. The most aggressive “look at me” thing I could do was to make something quiet and contemplative.

We really do measure ourselves in relation to the things we’re attached to. In emotional relationships or romantic relationships, so much of our identity is wrapped up in the things that we’re connected to.

Or the things we own. Our virtue is often judged on our attachment. “I’m attached to this house, therefore this is my virtue.” “I’m attached to this car, therefore this is my virtue.” And whenever you stray from that nonlinear path of upwards trajectory, it’s deemed as a failure, so I had to really negotiate that the ending of our band wasn’t a failure. This was a venture that did miraculously well! I was in synchronicity with four other human beings for most of my adult life, and we created work that we believed in. That, in itself, is remarkable. So, I had to talk myself down from that “abc” way of negotiating value.

The dream is always total creative freedom—the freedom to do whatever you want without anybody telling you not to—but that kind of freedom can be overwhelming. It can be a weird thing for a solo artist, to not just get lost in your own mind, or go down a rabbit hole that you can’t come out of, especially when there’s no one around you to say, “Yeah, that’s good,” or, “Maybe that’s not good.”

I went into making the record without a real sense of what it was going to sound like. I just had these piano songs, and I very much improvised on the record. I think that allowed me to, at least, avoid, as best I could, the swamps of my own mind.

Your limitations will define your work far more than your possibilities. It’s the negative space which determines the work, really. For instance, I regressed massively in terms of my production skills. I went from being able to co-produce the Wild Beasts records to being incapable of anything but an iPhone recording, because I realized that my attention was best kept to the intangible aspect of what I do, which is the songs hanging in the ether, or the words in the air, and the more abstract things that take their own focus and attention. So, I limited myself in some skill sets, in order to enable myself in others. And that can be greatly frustrating. Sometimes, I think I would love to just get to a studio and be able to put something down. But the truth is, I can’t. And I feel a bit insecure about that, in some respects, but I also feel stronger in other aspects.

How long was the process of making your solo record?

The gestation period of the writing was, funnily enough, nine months. Which is obviously, in human terms, a very symmetrical time for creation. I definitely created all the songs within the contortions of the landscape of my life, which was: the band had made the decision to not be a band anymore, but it was nine months before we could make the announcement. So, within that, there was a weird emotional latency—externally, I was the frontman of a band, doing these quite ballsy songs on festival stages and different places around the world, but, internally, there was this vast hole of uncertainty. Which, I guess, is what the work is there to bridge.

Had the idea of making a solo record, or doing something totally on your own, been in the periphery of your mind, even before the band ended?

I think so, but only in fantasy. There was no actual, realtime thought as to how that would play out. Like with all fantasies, there was also an aspect of fear about it. “Dare I be that guy?” And a solo album is a weighty thing to take to market. But in the end I am a firm believer that we are all made equal, and we are just the person we are according to the alignment and location of the people around us, so I probably did always have a solo record in me; it’s just that I didn’t need to have one in me until I needed to have one in me.

Did you find that the process of writing songs, or the way you thought about writing, felt way different when there was no one else to please but yourself?

The difference was, I started making music in my home again. Music had become something that existed external to my home. It became something that was done in studios, or in rehearsal rooms, or in spaces that required infrastructure—PA systems and loading capabilities. And then, it was a really beautiful sensation, how the songs existed in my living room. All of a sudden, that circle became closed up. That was something that I found really nourishing and essential.

Yeah, I would imagine that is kind of freeing. I was talking to a filmmaker yesterday and he was saying, “Oh, I really envy writers, because you can just do it. You don’t need to ask someone for money to do it; you don’t need to assemble a huge team of people to do it. You can just do it.”

Therein lies the equation. If your job depends on self-summoning, a huge part of the job becomes about self-maintenance. How do you keep your circuitry free enough to allow it to happen? And often that circuitry does require contortions. For me, it was the disparity between my external life and the secret I had, that things were very different. And that worked for those nine months.

So this is where the artistic agony comes from, where it’s like, “Do I have to stay in that contortion to create the work?” So, I think that is where the mythological psyche of the maker comes from. The best thing I try and do is to stay healthy enough to keep making, because the joy is in the making; the joy is in the doing. There isn’t any other.

Having the experience of being a front person in a band for a long time, you have a certain amount of experience in regards to what it’s like for people’s energy to be focused on you, or to be in front of people performing. But it is a different thing when you are a solo artist and it’s really all about you. How does that feel?

The scrutiny itself is more extreme than I even anticipated. Especially when you work in a way like I do, that requires self-interrogation. That’s not the blueprint for how to make work; it’s just the way that I do it. So, that level of meta-scrutiny has been a challenge, but also that’s real life, in that the only place I can find what I need is right here, so I might as well try and find it. And to sit at a piano, just me and the voice and the keys—you have to be able to dial in your attention pretty quickly. With a band, or with any collaboration, the nature of the work is determined by the character of the group, but when you’re on your own, you actually have to really go at everything with a particular intent.

Also, putting records out is all so glacial. Some of the songs I’m just now singing publicly for the first time were written and put together almost 18 months ago, and no one can carry the ember of an emotion for that long. It changes, and engulfs other things, and peters out. Even the word “falsetto,” in voice, implies falsity. So, I don’t get too hung up on trying to give an authentic performance. You just have to be in the moment. You have to be it. It’s a strange, strange thing to try and unpack. There is never anything more “now” than being on stage. There is no yesterday, there is no half an hour ago, and there is certainly no tomorrow. That’s the beauty of it, because if you think about it, the past is just a narrative, and the future is just a metaphysical assumption. So, that’s the beauty of being onstage—you are suspended, essentially, between those two states.

Do you find that the way you use your voice has changed?

Yeah, definitely. Within the band, the band being a family, I was definitely the mother. And that effeminate quality was what I wanted to express, and what I tried to express. Now, on my own, I’m able to be more 360 in my humanity, as it were.

So much of what was ever written about Wild Beasts was focused on your voice. People would say, “Oh, it’s a very acquired taste,” or, “It’s so unusual.” I guess, in the world of indie rock bands, or whatever, it was unusual, but I never thought it was that unusual. Did hearing any of that kind of stuff affect you?

No, I can’t say it did, because I couldn’t help it, and because it felt good to sing that way. I only do these things if they feel good, and whatever neural maintenance is going on by singing like that, it worked. Also, you’re up against the constructions of what you’re supposed to be doing, so a man is, potentially, not supposed to be singing like that in rock music, whereas in other kinds of music, Ghanaian music, for example, the most masculine form of singing is a very high falsetto.I have always found myself on the fringes, on the borderlines of what is considered acceptably masculine. You don’t have to stray too far from that to have absurdity thrown at you. As a practice, I always found singing like that to be very good for my wellbeing. Singing is good for you. It does good things for your body.

Do you find that your voice has changed a lot over time?

Yes. Technically, I was in places earlier in my career I couldn’t be at now. But now I feel like I can do more with less in a way. I hope that is a result of craftsmanship. And also, there’s less flamboyance. There’s less peacocking. I don’t have to fight so hard to be noticed. And once you have people’s attention, you can be a bit more composed about it.

One thing I know I can’t help is the emotionality of my singing. I can’t fundamentally help that. That’s just intrinsic, and whenever I try and release the intensity of that emotionality a bit, it goes flat. Again, that’s something that, within our society, in regards to masculinity, it’s not supposed to be that way. It’s not supposed to be emotional, and I think a lot of people have found this record, in particular, slightly affronting in its emotionality. Like, “Filter it down a bit, man.”

You know? It’s interesting, because of my voice, the sexuality of the music is also called into question, as if that should be a debate. As if the more feminine posturing of my voice at the moment, and the emotionality, implies something about where it is on the sexual bandwidth. I find that so interesting, too. And silly. Like, come on, guys! I thought we were past this!

Regardless of how much the dialogue about gender and masculinity within our culture has changed, about what we think of as being distinctly male or female, or what’s allowable, it’s still remarkable how little, particularly in certain kinds of music, that has not changed at all. That was what made seeing Wild Beasts, especially early on, so invigorating. It was so at odds with so much that was happening around it. But I think the hyper-emotionality of your voice is also what makes it distinctive. The thing that would be off-putting to some people would be the thing that makes other people love it.

Exactly. That’s the yin-yang of making work—that you’re never gonna really touch people unless you really fuck people up, and that’s something I’ve more than made my peace with. Songs are everything. The way I use songs, and the way that music exists in my life—there is no other, greater resource for consolation of the soul. Where else do you go for it? Where else do you pull strength from? Songs are an emotional antennae for us. They are that resource, so why would I dull that for fear of someone’s emotional landscape not allowing for it? You know?

For me, doing what I do requires my emotional kidney to be worn outside my body. So, I’m sorry for those of you who don’t want to see that or hear it, but in order for my blood to be cleaned, this is my dialysis. Therein also lies the job description: to tolerate exposure to that. I can’t say that always feels good. But I can’t say, also, that every song is true to life. You write yourself into being. There’s some days, and some moments, where I am the characters in my songs, but there’s definite moments where I’m not.

How will it be to go and play these solo songs? How will it feel?

It’s feels really vital, to be honest. Tonight, I’m alone with a piano in the venue, and traveling with a rucksack, and really just going to the instrument and playing the songs. I’ve become enchanted with the idea of the song being enough for me, the voice being enough. For now. That’s something that the career ladder of a musician, strangely enough, often robs from you. The better it goes, in some ways, the more you get peeled away from the vitalness of that. I think the best artists never lose it. The best, despite the scale of the venue, manage to somehow hold that umbilical link. You know when an act becomes untethered from that because it’s very apparent in your heart. So, at the moment, for me, playing shows is a real combination of humility and earnestness, because there’s no throne awaiting me. There’s no inheritance of listener. I have to be realistic on that front, that I am building an audience again. And that’s the equation for anyone as you try and make a go at this sort of career. It’s a nonlinear life path. But also, within that, there’s still the expectation of—I have to be good. All I’ve cared about since the age of 21 is songs; that’s what my job requirement has been. So, therefore, I better have some good songs and better be able to play them in a good way.

When you’re working on music, what do you do when it feels like something is not working?

It always feels better when you don’t have to convince yourself of something. So, as soon as you start to have to create scaffolding around an idea, you’re in trouble. That isn’t to say that there aren’t ideas that require some agonizing care, but you have to accept that you’re going to hemorrhage a lot of energy on ideas that just aren’t going to work out, and that the only thing that threatens you is an ego death. You need a certain amount of ego to do this, I think. You need a very inflatable ego, one that can become quite expansive, but also one that can shrink back down when necessary. You just have to keep an eye on it.

It is a complicated thing. For musicians it’s often this weird combination of, “I can go into a room full of 5,000 people, by myself, on stage, and do this, no problem,” but then also feel insecure about it at the same time.

I think it’s because the equation goes, “I am me if you let me be.” You need the people to let you be you. And that will always be a chaotic process, because sometimes you’ll get it and sometimes you won’t. And that’s something I’m still negotiating, really. Also, it is an audacious ask, to suggest or assume that your work is worthy of someone’s attention. But my understanding of that, as a process, is the reciprocity of, “Here is the exposure. Here is the guts of me.” And hopefully that is an offering that is enough. All we can do is make the offering.

Hayden Thorpe Recommends:

Without getting too sickly about it, I’d recommend always spending time in nature. I would say that whatever ego catastrophe you’re having, wherever you are on the ratio of worthiness, within nature, your worth always equates to the same thing—which is nothing. And everything. That is always the place where I get enough awe to gain perspective. And conceptually, the patterns of nature are within all art anyways. It’s always a great resource—nature provides our music, our color. That’s where I always go when I need some kind of gravity to bring me back down to earth and inspire me.

- Name

- Hayden Thorpe

- Vocation

- Musician

Some Things

Pagination