As told to Annie Bielski, 2801 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Mentorship, Inspiration, Adversity, Success.

On trusting your eye and being tested as an artist

Artist Phyllis Bramson on the process behind her paintings, the ways in which pleasure and sexuality inform her work, and the variety of ways the world tests you over the course of your career.How do you start a painting?

With a lot of fear and trepidation. It’s totally improvisational because I work with collage, and cut up found warehouse paintings. I’ll sometimes stick a fragment or two on, and just try to figure out where to go from there. I’ve begun to think that I make each piece so differently from the other, and I don’t think that’s the way the art world likes things at this point. I think they like increments of change. While you would know it’s my work, I think I just always liked the challenge of how I’m going to compose. I get myself into a lot of trouble and hot water, and I just have to work on it, and work on it. I think that’s why some of my paintings are so awkward and odd, because I’ve had to deal with mistakes that I’ve made, and tried to correct them in some way.

What are the warehouse paintings and how do you use them in your work?

They’re what you might call starving-artist paintings that go over a couch. They’re sometimes advertised that way. I feel it’s being very transgressive [to use them]. I think that my work deals with that gently. Sometimes they’re drop-dead beautiful. They really are beautiful paintings, but I think that’s what’s held me back in terms of trying to emulate them sometimes, they are kind of like masterpieces. I just don’t have that kind of a hand, so I fail at it. Maybe that’s part of the situation—in a way, they’re failed paintings. I do failed paintings because they fail to live up to the paintings that I’m cutting up.

Decoys, 84” x 72,” oil on canvas, 1989. Courtesy the Artist and Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.

I read that your father, who sold automobile parts wholesale, decorated the house you grew up in with statues and pictures of nude forms, ranging from calendars to pens. The nude or semi-nude makes a frequent appearance in your work, as well as knickknacks, picture frames, and other signifiers of domestic space. Could you speak about some of your earliest visual memories as they relate to your work?

He’d bring home these boxes of Christmas cards. They were beautiful, because we’re talking about the ’40s, early ’50s. Beautiful, beautiful cards. Nude calendars. Pens that if you turned them upside down, the woman would have no clothes on. Kind of salacious pin-up calendars. That aspect of looking at the nude form—because the house had nude statues everywhere, nude ashtrays—was something I was used to. That was part of my early visual training. It was a very eclectic house, which again, is why I think I am so comfortable with eclecticism in my own work. It’s funny because my mother would draw this ’40s kind of face, a profile, that I asked her to draw over and over again. Every once in a while, that face will pop up in my work.

Pleasure, sexuality, joy, humor, and something a little off—sometimes mischief, sometimes sorrow—are present across many of your paintings. What’s the relationship between these themes? Do they need each other?

A curator came to my studio last week. I told her that there are some people who say my work is dirty, and that when I thought about it, I kind of got insulted because I think they thought I was thinking of pornography, which of course I’m not. We were talking about it, and she said, “You know, I think your work is dirty and dainty.” I think if you’re talking about dirty as being covert sexuality, and the daintiness in terms of how I present it, I think that’s a very accurate way of talking about a lot of my work.

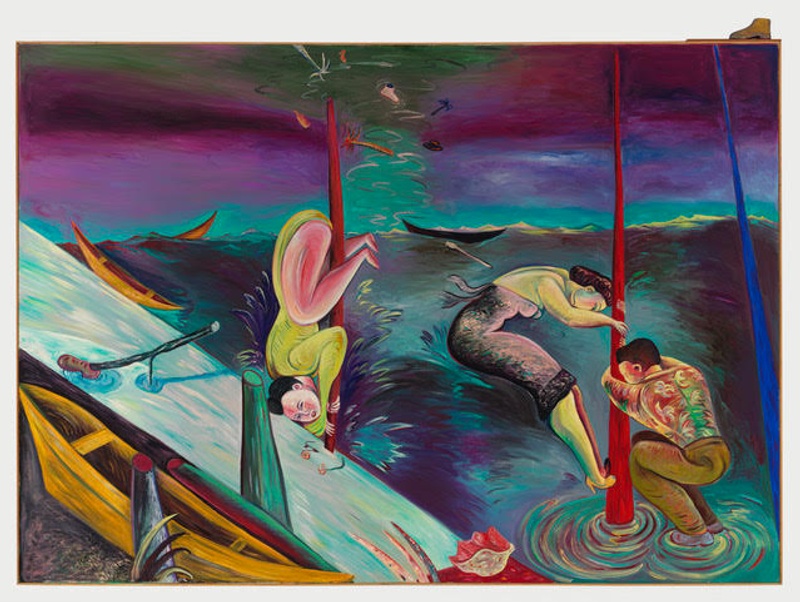

Shipwrecked, 72” x 96,” oil on canvas, 1987. Collection of The Krannert Art Museum.

I know there are times where I purposely pushed the sexuality, but what a lot of people don’t know is that many, many times there’s a funny clump of stuff, and it’s not exactly pleasant. It’s usually flowers or abstract shapes and they’re clumped. It’s almost like it’s an orgasm. Like the painting is having an orgasm. I always know when it’s going to happen, because it happens when I’m just exasperated. So I’ll make this sort of bizarre clump of some sort, that I know is inappropriate in a way, and it doesn’t look very good, but on the other hand it does.

Duality shows up a lot in your work: couples, pairings of objects. How do you think through duality in your life, studio, home?

I live a dual life. I’m married to somebody who’s not in the art world, and I don’t really share that. We’ve been married almost 60 years. I go home [to the suburbs] on Saturday nights, and come home [to my studio in Chicago] on Monday afternoon, usually. I go to a suburb where there’s a house that’s just a completely different life, just totally different. When I come home [to my studio in Chicago] sometimes on Mondays, I’m just fried from the other existence, and then trying to enter back, and just jumping in. I can’t usually do it. I have to rev up, and by the time I’m revved up, I leave again, and go home. It’s not so hard going home as it is coming back to the studio.

I’ve been doing that since 1985 when I got a full-time teaching position at the University of Illinois. I have to say it’s a little harder now, even though I’m not teaching full-time. I’m wondering how in the world I was able to have a career. I was pretty active showing in New York, and I had an active career. It’s not like it’s not active now, but it’s not as active as it was in the ’80s. Whereas the art world used to come to me, now I have to figure out how to get to the art world. I wish it was the reverse because I could use it more now. A curator came to visit me and said she has a lot of friends who are older. She said they don’t have the energy to deal with their newfound re-energized careers. It’s harder on them now than when they were younger.

Two years ago you had a retrospective at the Chicago Cultural Center. Was seeing a lot of your work presented together in that context a similar feeling at all to your mid-career retrospective in the ’80s at The Renaissance Society?

At the Renaissance Society at the University of Chicago, I wasn’t as grateful. I mean, that was a period when everything was just, “Oh, I’ve got this. I’ve got that. I’ve got this.” I didn’t really think about it. It just happened. I wasn’t as hands-on. It was controlled by this art critic, a man named Dennis Adrian. He controlled what was chosen. He wrote the essay. I just went along with the flow. I think it was more important than I realized at the time. All of a sudden, I was told I was having a show.

Then when I had the show at the Cultural Center, I had to ask, and ask, and ask, and ask. It was so complicated and difficult. Eventually, they said yes. I chose who I wanted to write for the exhibition, and it came about quite smoothly. Then I went to help hang the show, and the curator Nathan Mason had put everything around, but he just couldn’t pull it together. I was wondering too. There were certain things, they just didn’t look right. So I took the position that I probably take as a painter and as a curator myself. I went with color. I said, “Nathan, let’s try dealing with color,” because it wasn’t in chronological order. That worked. “Well, okay. Bring in other paintings about blue.” Oddly enough, they went together conceptually as well.

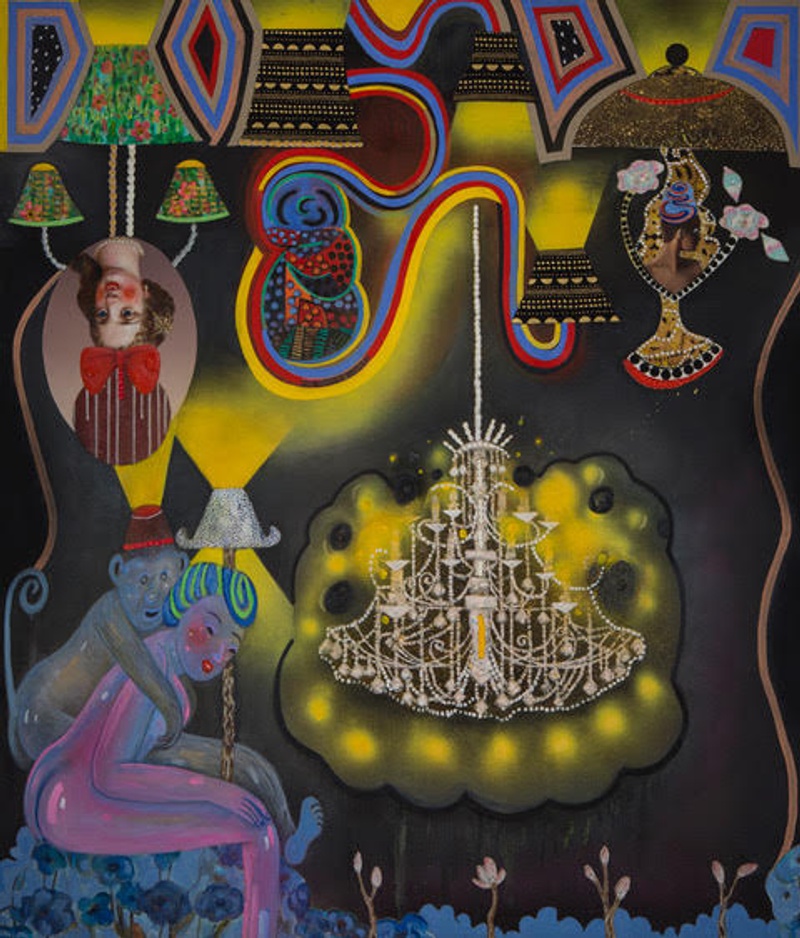

Glow, 60” x 70,” mixed media, collage, oil on canvas, 2017. Courtesy the Artist and Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.

It was very strange, but I think there’s some way, if you’ve got an eye for things. Even in my studio, if I start to look around, I’ll be surprised. “Wow. I didn’t realize I was putting this against that because boy, they really work.” You know what I mean? In my house, there are certain ways that I put things together, and I don’t do it on purpose. But one day I’ll look around and say, “Wow. Everything’s got this same pattern on this end of the building.” Then it changes to something else. It’s a visual curation.

Yeah, an unconscious sort of knowing.

I trust my eye. So when I compose, I don’t do it in a dedicated manner. For example, because I now advise graduate students at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago, I’ll say, “Why did you do that?” They say, “I’m balancing this with that.” And I’ll say, “It looks trite. It doesn’t work, and it’s a lousy reason. You’ll just do it automatically. Don’t purposely try to figure it out because it won’t work. It just will happen, and you’ve got to trust that’s going to happen because you obviously know already how to organize a composition.”

What has working with students for so long impressed upon you about trends or methods of working? Is the student of 2019 so different from the student of the 1980s?

The student of 2019 is looking at the internet, and maybe being very influenced by other artists. You can kind of see it. “Oh, that artist is looking at this artist.” I have kind of challenged students about that. Where when I was first teaching, you’d talk about artists more that were maybe historically of significance. I think that with any generation, even as a teacher, you’re teaching what you knew and followed. What I mean by that, when a student is coming straight out of undergraduate school showing their work to me, I’ll say, “How old was your teacher?” They’ll tell me, and I say, “Well, you know, that teacher is teaching from this particular period of time and I knew that about this person just by looking at your work.” I say, “He or she was teaching you from another period of time, so you’ve been pushed backwards, and now you need to go forward. You need to remove some of this overly determined, overly classical way of working.” Nowadays, I still see that, but as I said, I think the internet has more power.

Do you utilize a painterly approach to doing whatever you’re doing when you’re not painting?

Yeah, I don’t like to follow orders. I was taking a Zumba class, and the guy had these dance routines that we were supposed to memorize, and they got more and more complicated. Then he would do them, and then we would have to do them without him being there. So I went up to him and said, “I’m leaving this class,” I said, “Because you’re turning this into a dance class rather than a Zumba class.” He said, “This is good for your brain.” I said, “It’s not good for my brain because my brain doesn’t work this way.”

I think that it’s so interesting to see the different ways that artists work, because we all don’t work alike, as you know from your own work. It’s one thing I don’t like about graduate schools. I think that sometimes a faculty member will try to get the MFA candidate to work like they work, or to think like they think, and I think it’s really not fair to the student. They’re going to have a hell of a time when they get out trying to sort it out.

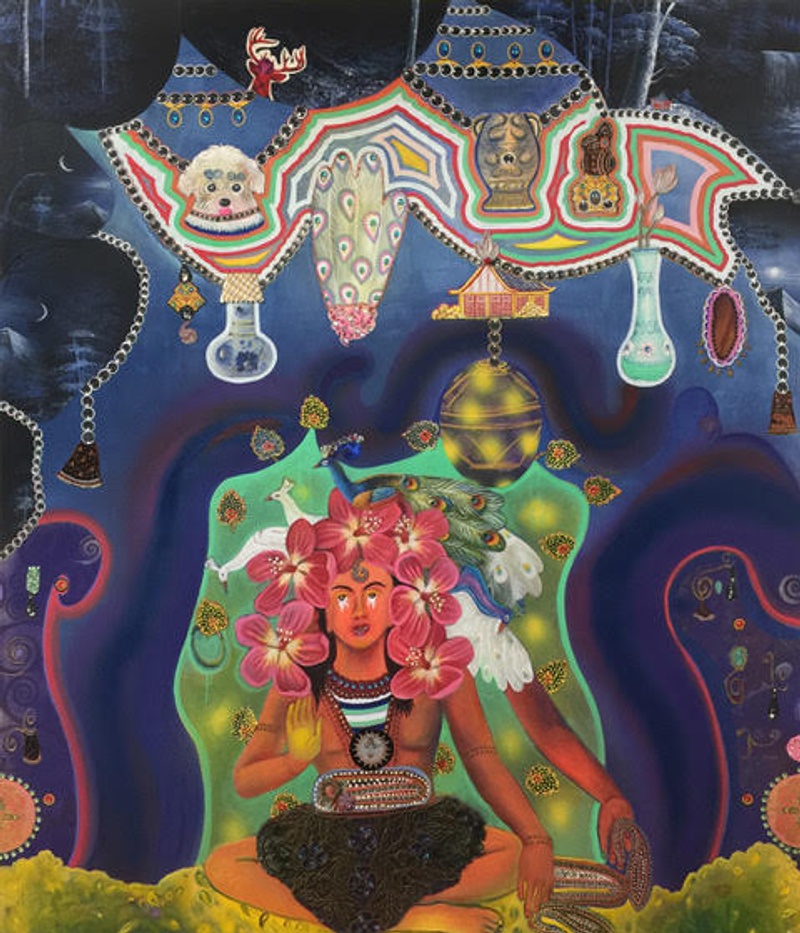

The Unhappy Keeper of Material Goods, 70” x 60,” mixed media, collage, oil on canvas, 2016. Courtesy the Artist and Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.

Could you speak about career ups and downs, or times when no one was paying attention? What advice could you give to artists who might be experiencing that?

Well, I think that’s the whole crux of a career. There are, I think, some artists who have a mechanism that maintains their power, whether they’re good or not. I think if you’re going to be an artist, you just have to figure out why you’re doing it. You get tested all the time. I’m being tested now, you know, because I do have friends outside of the art world, and they keep saying, “Well, when are you going to retire?” All the conversations are really about travel. It’s just ridiculous to me. I just say to them, “You know, I work for myself, and this is what I do. I have these obligations to maintain. I have these shows I’m getting ready for.” The conversation just stops. I think it’s easier when you’re with other artists.

Nicole Eisenman, I think, has maintained a very strong career. Sometimes she tries something different. She’s allowed, but I think on the whole, she has really maintained a very strong career. I don’t know if she’ll ever be out of favor. I’m not sure she will. It was her moment a while back. It’s her moment now. I think for most artists, if you’re serious enough, you’ll have a moment of some sort. What you do with that moment is another story. I think some people have flamed out. They just haven’t been able to handle it, or their lifestyle has gotten in the way of them being able to keep going. You have people like Louise Bourgeois, who I think again, was allowed to maintain a career and up until the end was quite a force to be reckoned with. I kind of think it’s great when it happens later in life when you might really need it, but mostly I think it happens early when you don’t even understand how special, or privileged, or lucky you are.

Honestly, I think the hardest thing about being an artist is controlling envy. I just think if you’re around people who are doing well, and if you aren’t exactly doing well, it can be hard to be able to handle that. My husband said it. “Somebody else’s success is not your failure. It’s just their success.”

I think there are lots of pitfalls and traps. Maybe there are in other industries too, same for anybody who’s in music, or film. The one advantage you have as an artist is you can keep making your work in your studio if nobody else around is interested, but I think the way people grow is when they are given these remarkable opportunities where they have to stretch themselves. That’s really important. It’s not vanity. It’s just the opportunity to grow in a way that you can’t when you’re just in your studio making your stuff.

We’re living in a contentious political and environmental time. Over the course of your career, have you addressed significant political moments in your work?

I did make some work during the Clarence Thomas hearings with Anita Hill. I was really mad. I think a lot of women made work about that. I listened to the hearings. I actually listen to public radio all day and all night. I’m not that interested in listening to music, and I think it’s because it gets me outside of my own self. I think these times are really very, very troubling. My work has always reflected trouble. I’ve called one of my shows Love and… what? Maybe something like Love in a Troubled World. So I’ve used that idea that the world is troubled, but there’s also love.

What are you curious about?

I’m curious about what will happen when I’m not here anymore, about whether my artwork will have a life afterwards because I’ve seen other people where it doesn’t happen exactly. There’s no mechanism for it to happen. I do have a curiosity about that. I’m always curious, and praying that I will make the most of my time here, that my next painting will be spectacular. I’m curious about, “Can I go forward? Can I do it?” which I think is something a lot of artists share.

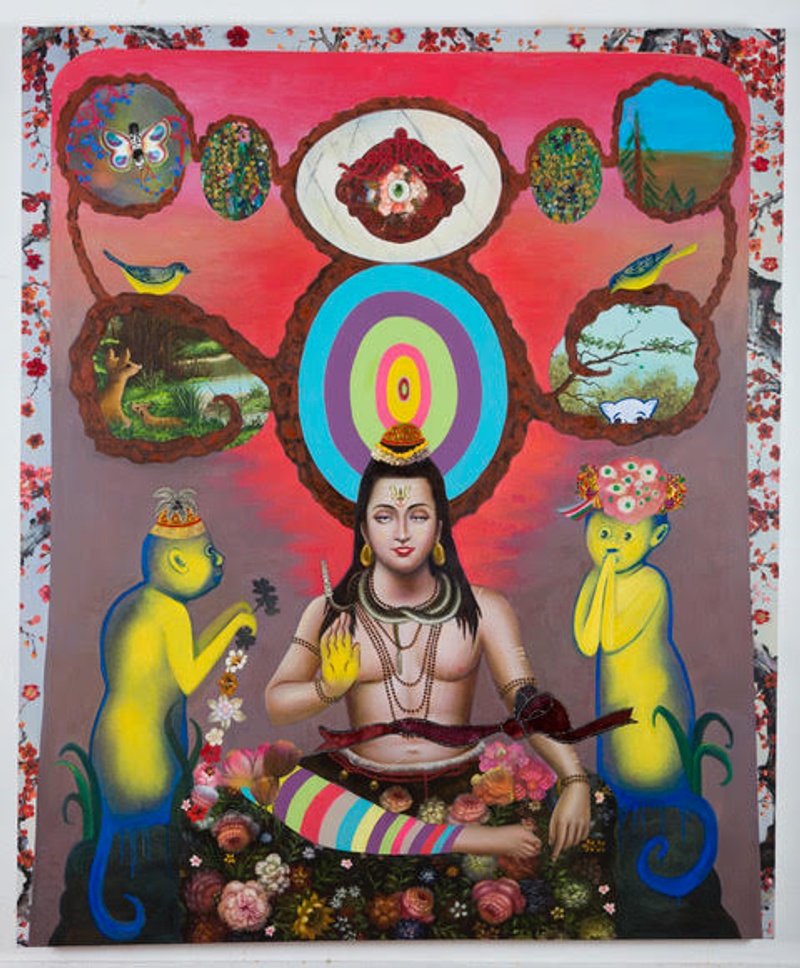

The Good Keeper of All Living Things, 70” x 60,” mixed media, collage, oil on canvas, 2016. Courtesy the Artist and Zolla/Lieberman Gallery.