As told to Kristen Felicetti, 2809 words.

Tags: Photography, Process, Mental health, Time management, Inspiration, Money.

On remaining curious

Photographer Stacy Kranitz discusses immersing yourself in what you do, the benefits of sticking to a schedule, and engaging with people through your work.How do you approach strangers about taking their picture? People can be very self-conscious or distrustful when a camera comes out, but your subjects always look comfortable and confident.

I use this approach that isn’t actually an official approach, it’s just what happens. I am insatiably curious about people and the camera has always been this excuse to interact with people who are different from me.

So I do this thing that I don’t think you should be doing in order to yield good photography, but it’s what I do. I talk through the whole entire shoot. I ask so many questions and I just use the time that I have with people to literally pummel them with my curiosity. And as a result, I end up with a lot of pictures that are people talking. They’re not usable, really.

But then in between those moments, it’s someone deeply engaged in the thinking of whatever question I asked, and I think that’s a really genuine, authentic place. They’re not self-conscious about the camera when they’re thinking about how they would like to answer a question that I might have posed. So I think in the end, I have to shoot a lot because so many of the pictures are people caught mid-sentence, but if there was a method, that’s it. I literally just talk through the whole entire thing.

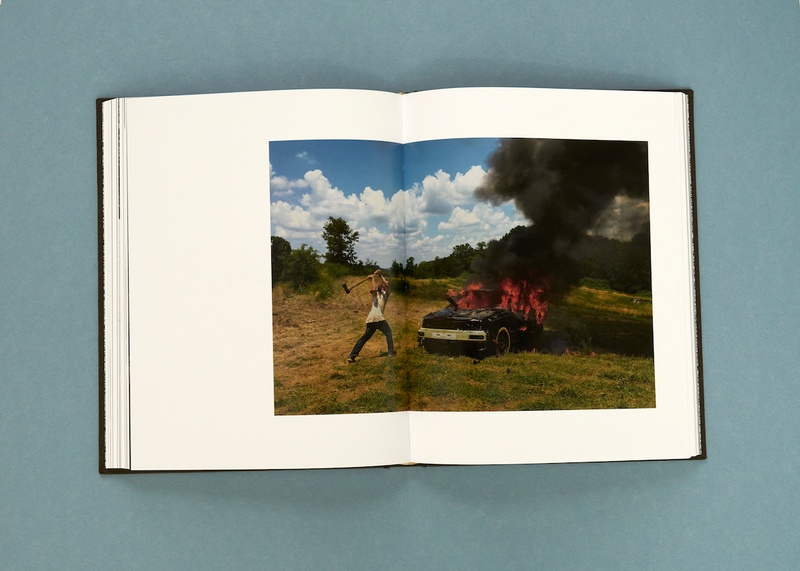

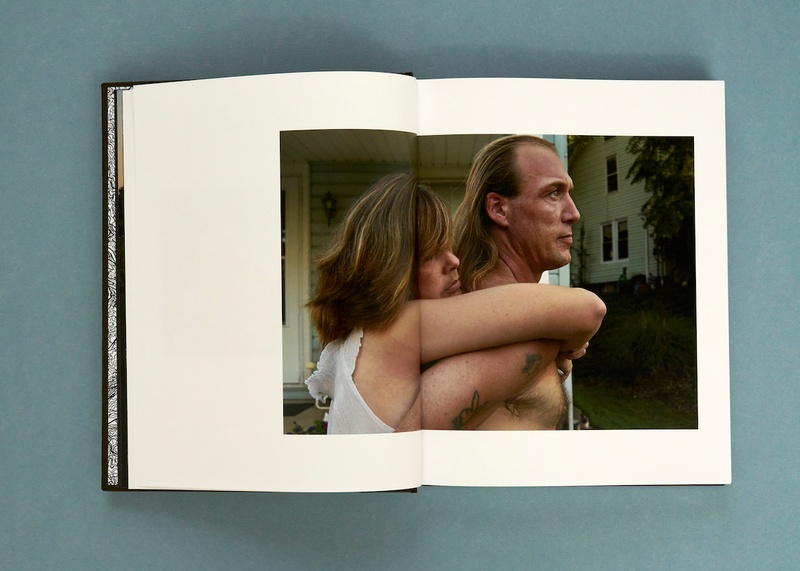

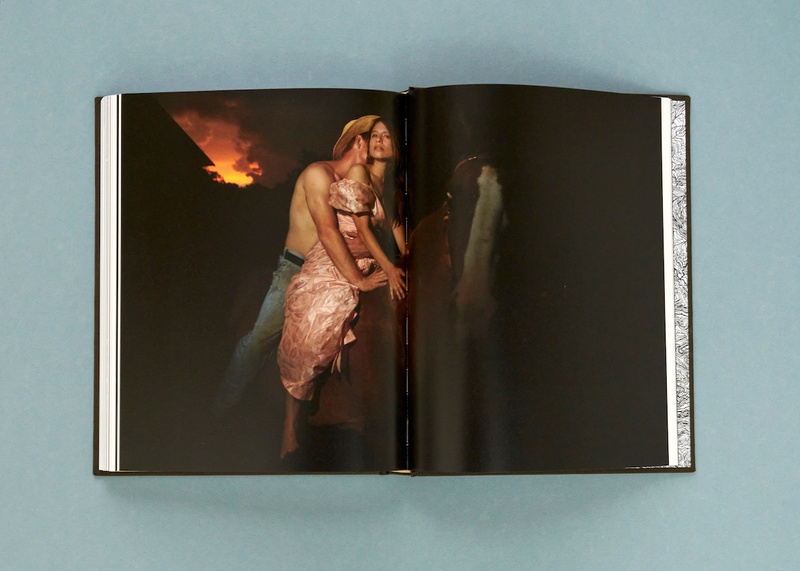

It’s interesting you mentioned being curious about people, because curiosity about people is something I associate with your work. A lot of the work in your recent book As it Was Give(n) to Me was made during a period of time when you lived with the people you photographed in Appalachia or lived out of your car. I’d love to hear more about that experience and what drives you to that intense way of working.

I was very dissatisfied with the work that I was making during the first five or six years that I had been a photographer, after my undergraduate education in photography. I was trying to understand what the problem was, what was making me so unhappy with the work. And it was essentially that I felt like the work lived on the surface of the ideas that I wanted to express, and I actually wanted to be making work that lived the idea. So I think, I felt like, “Okay, let me switch [to digital]. Let me take all that money that I spent on film and processing and put it into being out making pictures longer.”

And intimacy was something that kept coming up. I wanted my work to be more intimate. I wanted it to be more immersive. I wanted it to be more engaged. There was clearly a line that I wasn’t crossing. I felt like if I could cross that line, if I could find a way to immerse myself deeper, than I would like my work more. That’s really what I was thinking about.

I had a Honda Element, which is a fairly practical car. I would just sleep in the car because honestly, it’s expensive to stay in even a motel. Also, I thought that if I had a hotel or a motel, then I would go and hide in it, because if you’re out and you’re supposed to be doing this thing, which is engaging with people, there’s all kinds of reasons why you get afraid or uncomfortable or nervous.

But if you only have your car to sleep in, to hide in, and it’s so fucking hot during the day… I couldn’t sit in my car. So yeah, that method was really conducive in forcing me to not shy away from the work. That’s what that was about, and then it’s really nice how people, when they see that you’re living like that, they want to give you a shower or make sure that you have a place to stay. I think they are concerned about your safety. So a lot of people would invite me to sleep in my car, but on their property.

That does open up another intimate door. I could also sleep in their home, but even if I didn’t do that, I would still be able to wake up and go into the house and have a coffee with someone in the morning. It gave me a chance to have a really intimate experience with people.

You posted on Instagram about a time when you lost your confidence as an artist and almost gave up. What brought on that doubt, and how did you find passion for your work again?

I’ve only ever been a full-time artist. And I hope that doesn’t sound arrogant. It’s been an incredibly hard road where I’ve not made a ton of money. I’ve had to make a lot of choices. For example, to live in the middle of nowhere, so that my cost of living is really low, because if I lived in New York or LA, where I have lived in the past, I would have to have a second job.

But then in 2018, I was living in the middle of nowhere and my cost of living was really low and I still couldn’t support myself. I’d been doing this now for more than ten years. I felt like I had really gotten beyond that point, but I guess the lesson there is that you’re never beyond that point. I’m a freelancer, so there is such a lack of stability. Just when you think that things are moving in a really stable direction, they may not be, so it was awful.

I’m like, “Okay, what can I do? How are my skills applicable for a real world job that I could apply for?” And I don’t have a lot, because I’ve only ever done this, I’ve never had an office job. So then I was like, “Okay, let me try to make this thing work. What am I not doing? What is a revenue source that I didn’t quite see before?”

I came up with this ridiculous idea. I had seen other artists support themselves with grants. And I had had very little success with grants, but I was like, I just need to diversify my income, because I had been relying on editorial work to be the primary way that I paid the bills and supported the personal work. So I was like, “Okay, grants. If I can get 20 to 30% of my income from grants, that would be so helpful.”

The way I tackled that was I decided every morning from 8am until noon, I would write grants. I literally made it a part-time job. I wanted 30% of my income to come from that, so I wanted to make sure I was devoting 30% of my time to very seriously engaging with it, and I got a lot better at grant writing. I really started to understand what is basically a formula and a code that you need to unlock and way of communicating your work to potential funders, and then at the end of that year, I had gotten no grants. And I was so angry and so mortified that I had come up with this insane idea and it didn’t work, but also how did I even think it was going to work?

And then I was really in a bad place at that point, and then a few months after that, I got an email one day when I was literally sitting at my desk writing grants (I was still doing it, because I didn’t have some other idea yet of what to do). I got an email from the Guggenheim Foundation that said that I had got the grant. I do not want to go through the process of working out how long I’d spent writing grants that year and then realizing that I probably had only made like a minimum wage, but I did it!

Well, congratulations either way! I think when you hear about people winning those things, you’re like, “Oh, they just sent out their application and they got it.” It’s nice to know that even people who are very successful in their field are writing tons and tons of applications and getting rejections as well.

Tons of rejections. And I think that really changed my confidence in myself and also just being told that by some organization that a lot of people respect. Even though, if I really think about it, does it all really add up to mean anything more than how I felt about myself as an artist before I got that fellowship? But it does carry this weight and that weight is very internal for me. So that turned a lot around for me and then that confidence has helped me continue to find a more balanced way of making a living as an artist full-time.

I was really interested in the Works Consulted section at the end of As it Was Give(n) to Me. You did a lot of research, there’s hundreds of books and music and films and archives listed that inspired this project. And I don’t know if research is talked about as much, in relation to your work, compared to the going out and talking to strangers part.

I think the Works Consulted section is my most favorite section of the book. This is embarrassing, but I see it as a gift to the world to give a list of these incredible resources that so deeply inspired me.

I actually decided to do that because the formal monograph usually has an essay that’s written by a writer, often an academic or a curator. And I felt like that would’ve been really problematic for this work because I’m trying to push against this idea of asserting a right and a wrong onto how one looks at a place or a people or a body of work.

But at the same time, I did need to show the viewer that this work was anchored in a rich understanding of the place, a lot of time spent intensely researching. So I stole the concept actually from Leslie Jamison. She has a Works Consulted section in her book The Empathy Exams, and this is not original to me at all. But I really loved it. And I thought it was such a gift that she gave, and I wanted to do something along those lines. So that’s why I did it. Putting that together was such a wonderful, wonderful pleasure.

You mentioned the mornings you spent writing grants. When you’re not actively traveling or on an assignment, on those days that are just open, do you have any daily routine?

I do. I have a very…not a strict routine, but I have a pretty elaborate routine and I had to create it because I was really floundering in depression before I created the routine. And I would waste a lot of my day just daydreaming.

My schedule is I get up really early. I go to sleep really early and I get up really early. I’m a morning person. So I had to identify my best time of day and then you have to put the things that you hate the most and do them at your best time of day, which isn’t always great. But it is the best way for me to get things done.

So from 8:00 in the morning until noon, I write grants and I do all the other things I hate like invoicing, begging people to pay the invoices that I wrote a month before. I have to email, make sure I keep up to date with my inbox and those kinds of things. So I try to do the stuff that is the hardest and the most challenging for me during that time.

Then I take a really long break in the middle of the day, from 12:00 to 2:00, where I exercise, I swim or bike or run. I live in the woods, so I can do a lot of nice things outside. It’s great to break up the middle of that day with some physical time outside. And I walk the dog, I eat lunch. I meditate.

And, then in the afternoon, 2:00 to 7:00, that’s when I do studio, more creative work where I’m experimenting and playing with images. Sometimes I’m editing for an assignment. And then, in the evenings, that’s when I get to look at other people’s work. I’ll read, usually one fiction book and then one nonfiction book. I live in the middle of nowhere, so I just watch a lot of Criterion movies. I put something on, and then I pass out.

That sounds like a good schedule, honestly. I like sticking to a schedule because otherwise it can get a little chaotic or something.

Yeah, I think you mentioned this in your question, but because I’m moving from being out and traveling for work or making the work and then coming back into the home, that transition is jarring for me. Sometimes it’ll take me a day to get back into that. Yeah, and I hate that. I hate losing a day where I’m just daydreaming on the couch.

There’s something in daydreaming that’s useful, or at least that’s what I tell myself.

True. You do need to build out time for that, and I don’t in my more traditional schedule. So I agree, I think that is not useless time, but it feels useless and it makes me frustrated with myself. And there’s nothing I can do. That’s just the way I feel about it.

So sometimes, there’s a transition day between the two, but at least I have this schedule that I know that I’m moving towards getting back to.

Is there something about your work or your process that you’ve wanted to be asked, but haven’t been yet?

I think a lot of people misunderstand and they think that I am a very social person and that this is all very easy for me. And I really am a hermit. I’m very resistant to being around people and the camera is the thing that keeps me from being a very unhealthy hermit. It’s the thing that allows me to engage with the world, even when I truly deep down in my soul don’t want to. And I think in that way, it saves my life. So I don’t know if that’s a question that I want people to ask, but I guess it’s something that I want people to know that I am not, and I don’t think you have to be to make documentary work or to engage with people. I’m engaging with people because I am so afraid of them.

Stacy Kranitz Recommends:

The Book of the Dead, Muriel Rukeyser

I have a passion for works of art that depict workers’ rights and this collection of poems released in 2018 (with an introduction by the writer Catherine Venable Moore) tells the story of West Virginia’s Hawk’s Nest Tunnel Disaster. It is one of many works from the 1930s that poetically expand the documentary tradition.

Erie, Kevin Jerome Everson

This experimental documentary film is a series of vignettes that depict life in the rust belt communities of Ohio where Everson was born and raised. Everson has devised a working method like no other documentary filmmaker and developed a body of work that takes the viewer deep inside African American working class life.

My Life and Other Unfinished Business, Dolly Parton

Parton is a wonderful storyteller and the story of her life is filled with all kinds of exciting twists and turns but perhaps the best part of this book is her insistence on speaking so openly about sex and placing great value on its role in everyday life.

Hard Hitting Songs for Hard Hit People, Hazel Dickens

Dickens wrote some of the most heartbreaking songs about life in the coal mines and the fight for workers’ rights.

Wanda, Barbara Loden

This film speaks to being a woman in a way than no other before it ever has. It speak to a hopelessness and a helplessness that I feel inside myself and see in others around me but could never quite articulate until I saw this film.