On imagining another world

Prelude

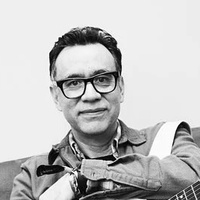

Jesse Feinman is a publisher and the founder of Pomegranate Press, a long-running independent imprint based out of New York City. He also owns and operates a small bookshop called Agony Books, which shares the mission of producing and distributing limited publications that are both accessible and supportive of emerging artists working within photography, design, and the like.

Conversation

On imagining another world

Publisher and photographer Jesse Feinman on unraveling gradually, finding your people amid the noise, and why he doesn't feel like the term "artist" really applies.

As told to Elena Saviano, 2254 words.

Tags: Publishing, Photography, Process, Beginnings, Independence, Business, Production.

You have kind of an elusive title. You seem like you wear many hats. Tell me about what you do in your own words.

First and foremost, I’m a publisher. That’s my main practice. I think it’s a sweet umbrella term, because the world of publishing is quite vast, and a lot of things fall under that. Using that as my title allows me to get away with a lot of different things, whereas other labels that I’ve tried to associate myself with felt a bit more constricting. I think the word “publisher” doesn’t come loaded with a sense of ego that other things might. Day by day, the roles that I take on vary, but I work very closely with other photographers, and my role shapeshifts between being an editor, a sequencer, a designer, a curator, a PR person, an order fulfillment person. I get to—and have to—wear a lot of different hats, for sure. I have my tentacles in all of these different pieces of the work. So that also always feels like a loaded question!

I’m sure. It’s asking you to oversimplify something that most definitely isn’t simple in any way. I’m interested in what words you feel are “loaded” when describing your work. Is “artist” one of them?

Yeah, I avoid that term. I avoid “curator.” I avoid “editor.” They just never felt right to me and seem to belong to somebody else.

Interesting. Why?

I only speak English, but I think it’s common in the English language that certain words become so distant from their original meaning. They become so overwrought. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with them, but words are association plays. When I hear the word “artist” in 2025, I don’t see anything resembling the silhouette of myself. I do make art, and I do curate, but to call myself that feels inaccurate.

That makes sense. Social media is so oversaturated. The word “artist” can just mean “personality,” and usage in that context deviates pretty drastically from the drive to actually be creative. But all of the work Pomegranate Press publishes does seem very intentional, and there’s a distinct awareness of the human condition present in all of it… How you decide if a project is a good fit for collaboration?

The immediate and honest answer is quite boring, but it’s just pure instinct. I’ve tried really hard over the years to go with that knee-jerk reaction to a body of work. If I have to chew on it for a long time, I will usually pass on it. I specialize in work that is personal narrative. I’m not trying to check any particular boxes when selecting images or selecting people to work with, but I am trying to ride this feeling. For a long time, I struggled with whether or not all I was doing was publishing the “pretty photos,” and that’s it. But as the project becomes a little more solidified, I’m like, yeah, that is what I do. I put out the pretty shit. I haven’t figured out what exactly there is to be said about that, but I look for work that is suggestive of possibility.

This goes without saying, but we live in a pretty difficult timeline, and there’s a lot to be really afraid of, and there’s a lot to be really upset about. I try to release work that doesn’t neglect that side of the human experience, but maybe suggests that there is a more complicated and complete thing happening. For every building on fire, there’s a new one being erected. In my day-to-day life, I’m not a particularly optimistic or hopeful or cheerful person, but I think it’s important to show work that is at least suggestive of that.

On a more literal level, I like to work with people who haven’t made many books before. I try to give room to people who are newer and emerging and haven’t made something.

Are you familiar with Studio Ghibli and Hayao Miyazaki?

Of course!

In every single interview that Miyazaki has ever done, he’s so cynical. He doesn’t appear optimistic at all. But he builds these untouchably bright and magical worlds. In a way, the work that we do becomes a chance to project a world we want to believe in.

I think to have anything resembling a revolutionary mindset—if you believe in a world where we can reimagine policing or social structures or class uplifting—it has to come with this unwavering, maybe unrealistic sense of optimism. If we’re going off of purely empirical evidence, and looking at the scope of human suffering and failure, there’s not really enough there to be like, “It’s going to be awesome in a few years!”

In truth, there are so many facets of what I do that are so frustrating and disappointing and discouraging, but I still have this thing in the back of my head that is telling me that whatever I’m trying to say hasn’t fully come out yet. I just have to keep doing it. Maybe the whole point of all of this is that I’ll never feel like I actually said it. You kind of have to make this social contract with yourself. This is not realistic, this is not rooted in reality, this is not profitable. But I have to do it.

For lack of a better word, it’s a calling of sorts.

Right, and I’m getting more comfortable with the notion that I am the right person for this. Whatever the qualities are that you [need] to build something like this, I have to acknowledge that I do have those. Did I ask for those qualities? No! It just came out that way. Whatever song that was playing, I did hear it, you know?

You mentioned that there are certain aspects of your work that are frustrating. How do you learn to work with those?

I get angry emails from strangers. People not knowing anything about me but randomly having a large sense of entitlement. Demands. Books getting damaged in transit. Printers printing things incorrectly. As much as I love them, the post office is frustrating. Books are heavy, and I have to move them a lot. Dealing with the market of capitalism. Tariffs.

Do you have a team?

No, it’s just me.

Wow. If I’m not mistaken, you started this pretty young?

I was 19!

It is so difficult to start and manage an independent business, period—let alone when you’re a teenager.

At the time, I had no idea and no expectation. It was my friend Alex, who left quite early in the project, and me. I started taking it seriously when other people did. I try to eschew anything resembling hubris or pride, but I am happy to share that we started by putting in $250 to make the first book, and that’s it.

I genuinely see your books everywhere. In coffee shops, bookstores from coast to coast, fairs.

I do pop up in funny places. [*laughs*] And I opened up a bookstore five years ago, when I was 25, and it’s important to note that we had no investors, no credit cards, no loans, no GoFundMe. We just kind of made it happen. I never share that publicly, but I think it’s important only because I want people to know that it’s possible… I think the reason that people don’t start their own imprints—whether it’s a publishing company or a record label or a shop or a brand—is that they feel there’s this huge barrier of entry. I think the only one that exists is time. You have to understand that it’s going to be slow, and things are going to unravel gradually.

Anyone who starts anything has hope, but very few people probably expect grand success. I love the usage of the word “slow,” because the idea of slowness is at the root of this analog resurgence we’re witnessing. I’m interested in how you relate to that notion.

It’s funny, because I think I go really, really fast. I am so attuned to the cost of things and the general size of the audience for books, and I’m also really attuned to the fact that I occupy a really specific space in the independent publishing world. It’s not quite a fan zine, it’s not quite a gallery-level artist monograph; it’s this thing in the middle. From a bookmaking perspective, there’s a lot of compromises. They’re condensed, concise objects. In that sense, I tell the people I work with, let’s just go. Let’s not be overwrought with overthinking, let’s not become married to particular ideas. Let’s not project these notions of perfection onto this object that is intended to be ephemeral, that most people are going to forget about.

Inversely, while everyone is most likely going to look at this thing once and never pick it up again, the whole point of what I do is celebratory. It’s a celebratory response to creation. So as a response, I’m like, let’s not spend a decade cradling it. Nothing I do feels done until it leaves my hands and enters someone else’s. There’s a lot of conversations about that. When I design a t-shirt or a sticker or whatever, I’m like, this is sick, let’s go. Move on. But at the same time, I’ve learned and accepted that the world does not spin as fast as the mind does, so while I love being a workhorse and making 10-12 books a year and however many pieces of merch, I understand and accept that in reality, some things take a lot of time. It’s this constant contradiction. It’s somehow harder to overcome hours than years, you know? Nothing I do feels done until it leaves my hands and enters someone else’s.Pom is an exercise in preciousness, about mitigating the relationship between working meticulously and cautiously and intentionally while also fostering serendipity and spontaneity.</span>

How do you navigate the space that we live in now, where physical media is making a massive comeback but also steadily fading into a digitally dominated landscape?

I think on some biological level, people crave touch and interaction. I’m no exception to that rule. People want to be able to feel this tactile object in their hands. I’ve known from a really young age that I feel a lot better when I have made something and can hold it in my own hands. It’s such a blessing and privilege that other people find something beautiful [about] these things that I’ve spent so much time with. In terms of art and culture leaning into a digital space, I honestly don’t really think about it. I’ve just accepted it. I had a conversation with a friend maybe a year ago where I was like, “I think I’m just a moodboard.” Because I have access to this information, I can see how many people save things that I’ve made, and it’s obviously a lot more than sales. I just try not to lose sleep over it. If people go to the Pomegranate Press Instagram and think, “That shit is a vibe,” alright.

Sometimes I feel afraid that I’m resisting change or unavoidable technological development.

I think there is this resurgence happening, for sure. And it’s seen as hot to be well-read. There’s almost a fetishization of books as an object happening right now. Am I benefitting from that? I don’t think so. But I’m aware of it. And this goes back to what I said earlier about unwavering optimism. There’s so much noise all the time, and it’s about finding the right people. The right moments. The right tenderness in the really busy, loud crowd. I’m trying to build a world. I’m trying to turn what it means to be a publisher on its head. I started this project when I was 19, and now I’m 30. When I look at who is publishing consistently in photography and who is tabling at fairs, I’m still the youngest one, a decade later, which is crazy! People are publishing zines, yes, and maybe this is too Sisyphean, but I try to be a good example. I want to show people that you can be young and make it work. And that definitely goes back to that idea of slowness. You can be young and kind of stupid. I didn’t go to school for any of this. Nobody wanted to help me. I just figured it out.

Jesse Feinman recommends:

Watching Mauvais Sang by Leos Carax. Denis Lavant’s closing monologue is one of the most beautifully composed speeches (rivaling Roy Batty’s in Blade Runner).

Listening to any cassette tape from the record label Janushoved. Internazionale’s The Opaline Dancer might be the best, though!

Drinking a crisp can of seltzer on an aimless walk. In a perfect world, you end up in Fort Greene Park with a friend who has a deck of cards.

Committing to the bit for as long as possible. To quote Robert Creeley, “Perhaps humor is the perception that we are (finally) without defense, once we recognize this we are literally alive.” Be FUNNY!

Finding any book by Anne Waldman, Frank O’Hara, George Platt Lynes, Duane Michals, Ihei Kimura, Eileen Myles, Tom Clark, Sandro Penna. If it’s published by Angel Hair, Twin Palms, Black Sparrow, or New Directions, you will be in good hands!

- Name

- Jesse Feinman

- Vocation

- publisher, photographer

Some Things

Pagination