On finding inspiration in the materials around you

Prelude

Agathe Snow (b. 1976, Corsica, France) lives and works in Long Island, NY. She has shown nationally at the Brant Foundation, Greenwich, CT; New Museum, New York, NY; the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, NY; and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY. Snow has also achieved international recognition, exhibiting at several prestigious institutions, such as Deutsche Guggenheim, Berlin, Germany; Jeu de Paume, Paris, France; Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France; and Saatchi Gallery, London, UK. Snow’s work is included in the permanent collection of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, NY; the Charles Saatchi Collection, London, UK; the Zabludowitz Collection; and in the Dikeou Collection, Denver, CO.

Conversation

On finding inspiration in the materials around you

Visual artist Agathe Snow discusses making art from discarded materials, the ways her family’s mushroom business connects to her work, and how her process has changed and stayed the same over the years.

As told to Annie Bielski, 2388 words.

Tags: Art, Process, Inspiration, Identity, Beginnings.

Where are you?

I’m out delivering mushrooms and I saw the fish market, so I’m parked in the parking lot. I can see the sea, I’m enjoying it.

Tell me about the mushrooms.

The mushrooms. [My family] has been growing mushrooms for a few years. [My partner] Anthony built all these places to grow them in upcycled materials, and it’s really doing well. I’m really excited because brand new mushrooms that we started from scratch—it is amazing. The mushrooms are so sculptural, and I realized that so many artists were really into mushrooms, too—John Cage, [Robert] Rauschenberg—so I feel a sense of continuation. I want to keep the mushrooms going.

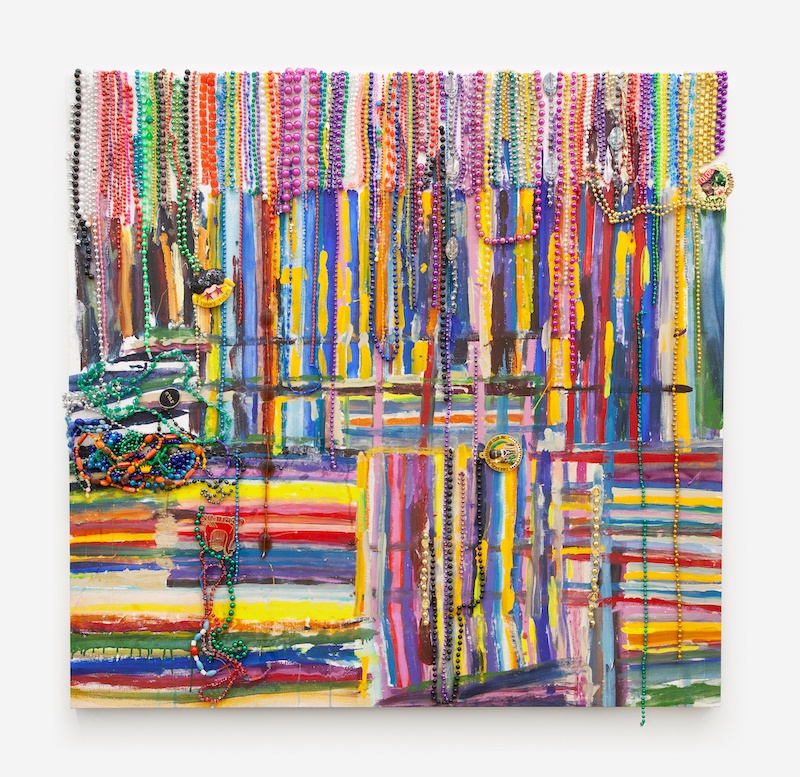

The doorway not USED, 2021. Acrylic, enamel, and multicolored Mardi Gras beads on canvas, 50 x 45 inches. Courtesy of Morán Morán.

I am thinking about all of your work, including food, performance, and sculpture. There’s a sense of joining together, whether it be with people in a space, or discarded materials to each other. I know that mushrooms are incredibly adept at communicating with one another and operate in a sophisticated network. There is some thread here with you, the artist, and the intelligent mushrooms.

I think so. When everything was shut down, I honestly believed that I was turning into a mushroom. There’s no doubt in my mind that I’m part mushroom now. I started making things six feet away, and was trying to paint six feet away, eat six feet away. The mushrooms were sporing everywhere and were communicating with everything, and I was stuck by myself six feet away from everything, wishing I was a mushroom, because then at least [my spores] could travel and get me closer to things.

Now I want to use them more in a way that’s more sculptural, use them as material, and involve them in the whole situation. I’ve always liked including [in my artwork], basically, the things that mushrooms grow in, pieces of wood that are discarded, rusted, stuff like that. I’m not kidding, I’m really thinking all these things were eaten by mushrooms to start with. Food for mushrooms. I’m kind of excited. We’re on the same wavelength.

Now [researchers] are realizing we can use mushrooms to soak up gasoline and soak up all this discarded stuff. In my work, I’ve used things made out of petroleum, like vacuum cleaners, and then I would break it up and make something else with it, or just use it as a prop or something. I basically try to reuse a material as often as possible and give it some extended life. The mushrooms apparently can eat all that stuff, so all of a sudden, I’m like, “Okay, finally, I can find some way of getting rid of it.”

video still, Distant Sporing, 2020.

What is a typical week for you in terms of art making and farming?

Right now I’m working on a solo show. The farm takes a lot of time, you’re basically there all the time, and at any minute, I just jump in and out of the farm. But, I decided I needed to really focus on my artwork right now, and so I have Monday and Tuesday fully devoted to the artwork. Wednesday is a hybrid day. Thursday and Friday, fully devoted to the farm, and then Saturday is for [my son] Cyrus, and always the farm and then some art. That’s how my week is really spent these days. Basically, I’m making paintings for the first time for this show, and also making a video.

With the farm, the mushrooms are constantly growing. It’s not seasonal. We may change. Some grow better in winter and some grow better in the spring, but basically you’re constantly working. They also grow super-fast, unlike most vegetables where you put your seed in and then three months later, you have a fully grown vegetable. With the mushroom, it’s very fast-paced agriculture. It’s very involved. At the same time, we really can’t go wrong. They’re very generous. They will grow in everything. I can deal with that.

I never thought I had a great ability to grow any vegetables or anything. The first year Cyrus was born, I think he was six months old, and we were living in a little farm out here, and I started putting seeds in this tiny six by four little plot. Everything was growing incredibly well—the most gigantic vegetables, the zucchinis—it was endless. The next year, when we moved to this place, I couldn’t make one single vegetable grow or they would come really tiny. I realized I didn’t know anything about agriculture back then, but now, I know a lot more. [Back then] we were living next to a sod farm, so they basically grow grass constantly and all the nasty chemicals and fertilizers they were putting in it were making my vegetables grow. They would grow humongous, I thought I had the best green thumb! But, it was all chemicals. I was force feeding my baby all that nasty shit. Anyway, the health aspect of mushrooms is amazing. More and more, they’re discovering the benefits—anti inflammatory, for brain disease, for aging of the cells, stuff like that. Mushrooms have just crazy amazing health benefits. That’s been amazing to find out, too.

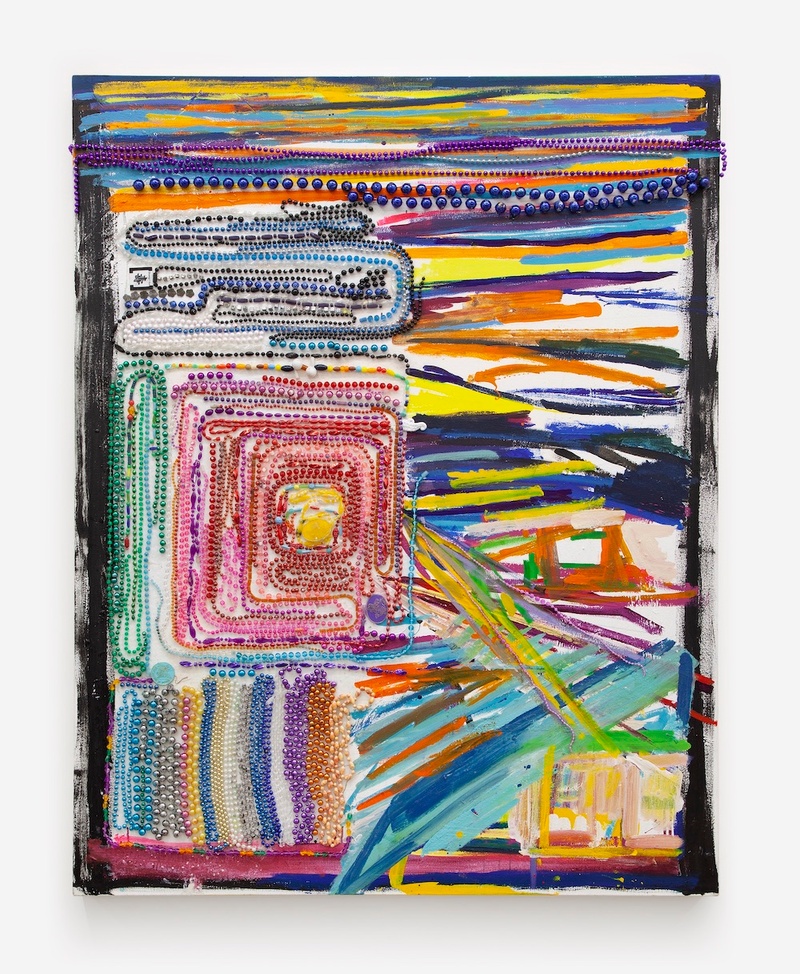

Moon and Sun Gamble, 2021. Acrylic, enamel, and multicolored Mardi Gras beads on canvas, 50 x 52 inches. Courtesy of Morán Morán.

For the paintings, after two years of [the pandemic], I was like, “What was the first indication that this was a really crazy moment we were dealing with?” For me, it was when a bunch of people got sick after Mardis Gras, so that was pretty early on. I decided to use all Mardi Gras beads for the props for the video and for the paintings. It’s really not at all what I would think of myself as making, lines mixed in with Mardi Gras beads on the canvas. That’s what I’m working on right now. The Mardi Gras beads gives it a little three dimensional thing, and since they weren’t used for the last two years, I bought tons and tons of them for very cheap.

And the video—I come from Corsica. My dad lived in the countryside on the road to Bonifatu, one of the first mountain refuges. My mom lived in Calvi Citadel, which is the super old part of the fortress town of Calvi. It basically belonged to the principality of Genoa in Italy for 400 years or something. When I was a little kid they said that Christopher Columbus was born in that town. We grew up in the citadel, and right around the corner from where we lived was supposed to be Christopher Columbus’ house, and Napoleon’s house was a few hours away. When we left Corsica and went to America, it was always, “Yeah, Christopher Columbus, Napoleon,” I was really proud of them. Then, [in the last few years], I started looking into Christopher Columbus closer. He’s the most atrocious person. For the video, I’m basically going to turn into a Christopher Columbus statue, and then I’m going to fight with him.

Where I grew up there’s a big religious influence. Every month somebody walks down the mountain and then up the old city with a cross on his back, carrying a Virgin Mary statue. The church rings the bell at the hour and then the half hour. You really are completely surrounded by the church, the holidays, and saint days all the time. Christopher Columbus really thought he had some kind of a vision from god, and was a representative of god, and meanwhile he was enslaving people. They even thought about making him a saint. I want to fight with that too. I think I’m going to have to carry a cross all over the city or a cross on my back. I always use humor, it just passes better. I find so much humor in my own situation. I wish I was better with words. Some people are so good with puns. I don’t have that at all. But, hopefully I create situations that humor can come out of.

The Most Public of Hours, 2021. Acrylic, enamel, and multicolored Mardi Gras beads on canvas. 53 x 41 inches. Courtesy of Morán Morán.

Do you ever abandon a project?

I’m never out of ideas, but I don’t always have the outlet to make the things I want to make. I wouldn’t abandon it so much as destroy a lot of work and reuse the materials. I haven’t learned how to keep things for the future. It always surprises me how older men with retrospectives keep things for 50 years, 60 years. Even one work of each show would be amazing, but it’s just so much storage and so much space. I sell work, but it’s still amazing how much it accumulates. There’s so much self interest and confidence and you have to be so sure that this is worth your time and worth the space.

I hate making space. I always thought that I took so much space from moving around so much. Things got destroyed very often in my life. With art, I don’t want to create more weight on the planet. I’ve always been very conscious of creating weight and taking space. To have things just laying about is really hard to deal with, but I guess you have to stand by your work and say, “Okay, this is worth keeping.” I don’t know if it’s so much abandoning projects as not believing in keeping.

A few steps from me, 2021. Acrylic, enamel, and multicolored Mardi Gras beads on canvas. 25 x 51 inches. Courtesy of Morán Morán.

How do you start a new project?

It’s funny. Before, it used to be that I’d travel somewhere. I always had a storyline, some kind of grounding element. I used to go somewhere and just take over a space and go find things and find elements. That was how I used to do it. But since I had Cyrus I’ve had to do things only in the studio and shift it, so it’s very different for me now. I’m constantly writing in my book and coming up with things, mostly from things I read. I have all these ideas and I just write them and then some make it out. Most of them don’t. I was reading [Jorge Luis] Borges’ Labyrinths about six months ago. That really spoke to me, and that’s when I started doing the [painting series titled] Endless Sunsets. It’s like a labyrinth, something you can never get out of and there’s really no point in it, a brain maze kind of thing.

I think that’s how things grow, just from ideas. Now, doing everything from home, I kind of have to make a story that’s different than before. It used to be very much about the now and the present, what was going on in that moment. It was all about researching others. It was like crowds are the protagonist, or humankind as a whole, monument makers, or whatever. Now, I’m more by myself, so the protagonist could be working in the woods or the family unit.

My dream would be to make a very universal work, something that you’d have no idea who made it—a child, an adult, a man, a woman. Talking from my own personal experiences is a bit hard, because I think it transpires very quickly that I am a woman. I saw this Mary Heilmann painting about four or five years ago, and I could not tell. It was made from home paints, I guess, the colors were off, so I thought it could have been somebody finding paint in their basement and doing something.

That’s another thing, materials. It’s always something I kind of fall into. They just kind of find me, or I find them, and then that’s how the paintings grow or that’s how the sculptures grow. There’s a lot of rusting metal and stuff in my woods, so I take elements of things that were in use in the early ’80s and are coming out of the ground now. I guess they had covered it all up, but the trees grow, it’s a new woods now and they’re all coming back up. I have TVs just popping up, and lots of agricultural tools. Not a single bit of plastic, so that’s another realization, just how much and how soon the plastic took over everything in the last 10, 20 years.

Video still, Distant Sporing, 2020.

The surprise of old TVs popping up in the woods after a rain or something brings me back to foraging again.

Oh, yeah. I love it. My dad used to take me to a local dump on a hill in Corsica when I was little. It had a big drop, and they’d burn it once a week, and people could rummage for parts and things. We grew up with really nothing, but he would take me to the dump and it was like going shopping. It was the best, just finding all sorts of cool stuff. My uncle told me, when he saw my work early on, that I’ve always made things, the same things, as when I was a little kid. It’s always been part of me, looking and finding things.

Agathe Snow Recommends:

Entangled Life: How Fungi Make Our Worlds, Change Our Minds & Shape Our Futures by Merlin Sheldrake

Azurescens mushrooms

Labyrinths: Selected Stories & Other Writings by Jorge Luis Borges

Katherine Bradford at Anton Kern

- Name

- Agathe Snow

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination