On creating spaces for joy

Prelude

Syrus Marcus Ware is a Toronto visual artist, activist, scholar, and educator. Working within the mediums of painting, installation, and performance, his work explores the spaces between and around identities, and has been exhibited at the Toronto Biennal of Art, the Art Gallery of Ontario, and more. He’s a founding member of the Prison Justice Action Committee of Toronto, worked with Blackness Yes! to produce Blockorama (the Black queer and trans stage at Pride Toronto), and has written and edited numerous books including Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada. Ware is a core team member of Black Lives Matter Toronto, and currently teaches at McMaster University’s School of the Arts.

Conversation

On creating spaces for joy

Visual artist and educator Syrus Marcus Ware on collective care, self-care, moving beyond statements to action, learning from your community's elders, and how his art and activism inform each other.

As told to Max Mertens, 3536 words.

Tags: Art, Activism, Education, Performance, Inspiration, Identity, Multi-tasking, Politics, Mentorship, Education.

You’re a visual artist, community activist, scholar, and you’re a DJ. Do these different pursuits blend together into one practice or do you feel like they’re separate parts of your life?

No, they definitely intertwine and are interwoven. I’ve been organizing and doing activism for 25 years, and I’ve also been an artist for 25 years. I started my creative practice around the same time I started getting involved with direct action organizing, so to me, they’ve always informed each other. My art practice is informed by Black activist culture and the organizing that I’ve done, and my activism is creative, it’s arts-informed, it’s arts-led.

They’re intertwined and what I write about largely as a scholar is also getting at similar things, trying to push for social change and systemic change in the field of disability studies or trans studies, or working to try to make some of the systemic changes that we need to see happen in institutions. That is largely driven by my activist work and my own experiences as an artist.

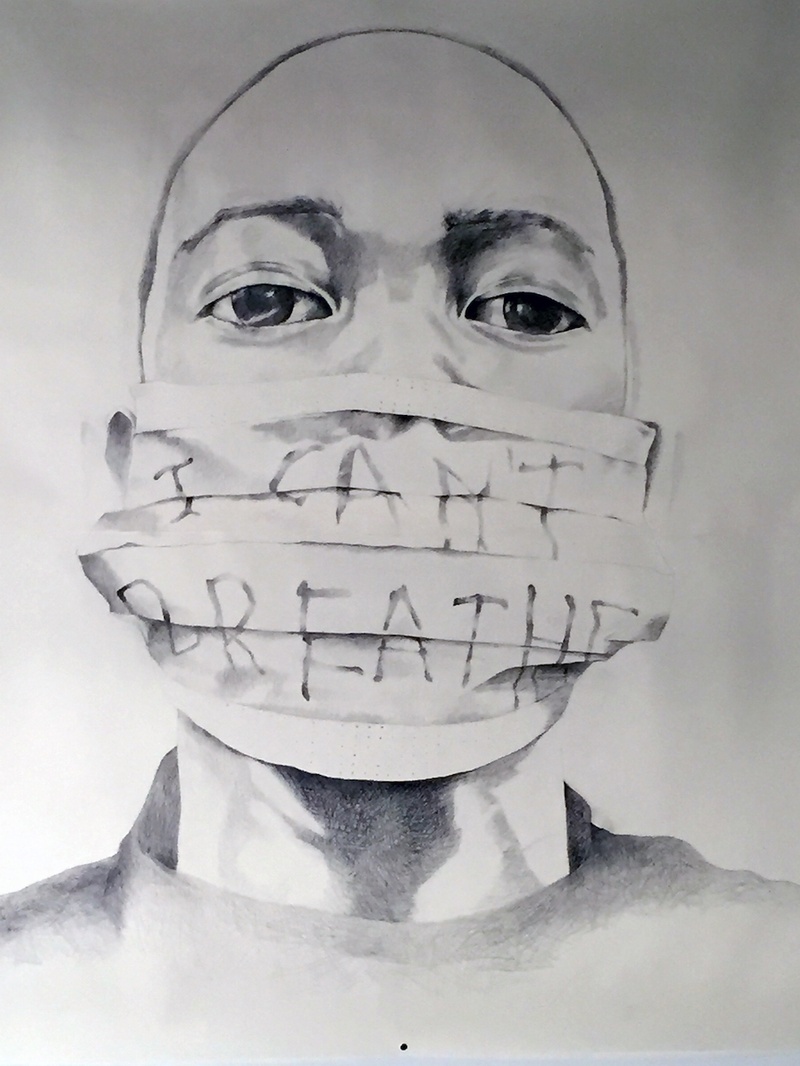

Syrus Marcus Ware, Their Borders Crossed Us: For Eric, 2015

How did you first get into making art and how has your artistic process evolved over the years?

I started making art as a child, my mom is an artist, my grandmother was an artist, so I was always encouraged to be creative. I went to art school for university and was making political work, work about social change, system change, and I was repeatedly told that my work was too overt or too political because that art wasn’t de rigueur. It wasn’t in style at the time. Post-modernism was in style at the time and so we were encouraged to do work that was more abstract in terms of the theoretical underpinnings. Luckily I didn’t listen and continued going down the direction that I wanted to go down, which was to make work that was about the experience of becoming politicized, about my experience as an activist, and that was about sustaining activism and figuring out ways to support and nourish activists and organizers in the struggle. They need the support in order to not burn out and continue working and organizing.

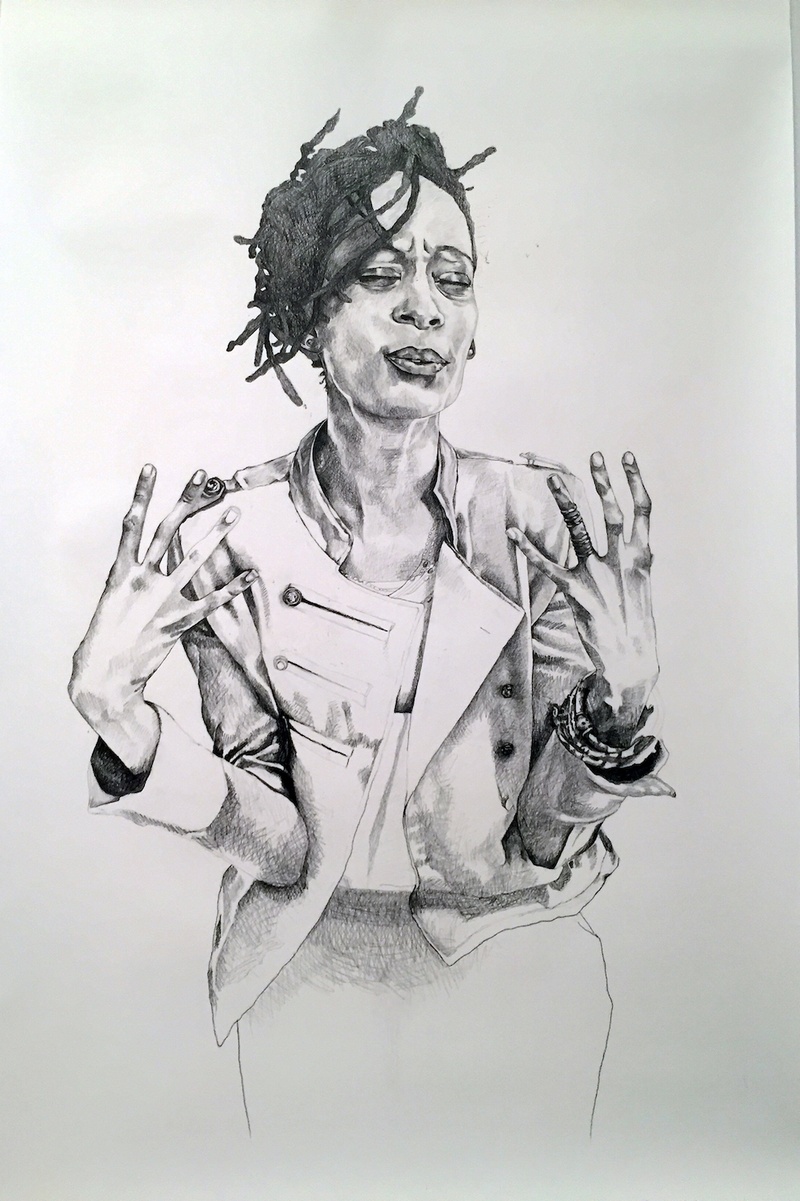

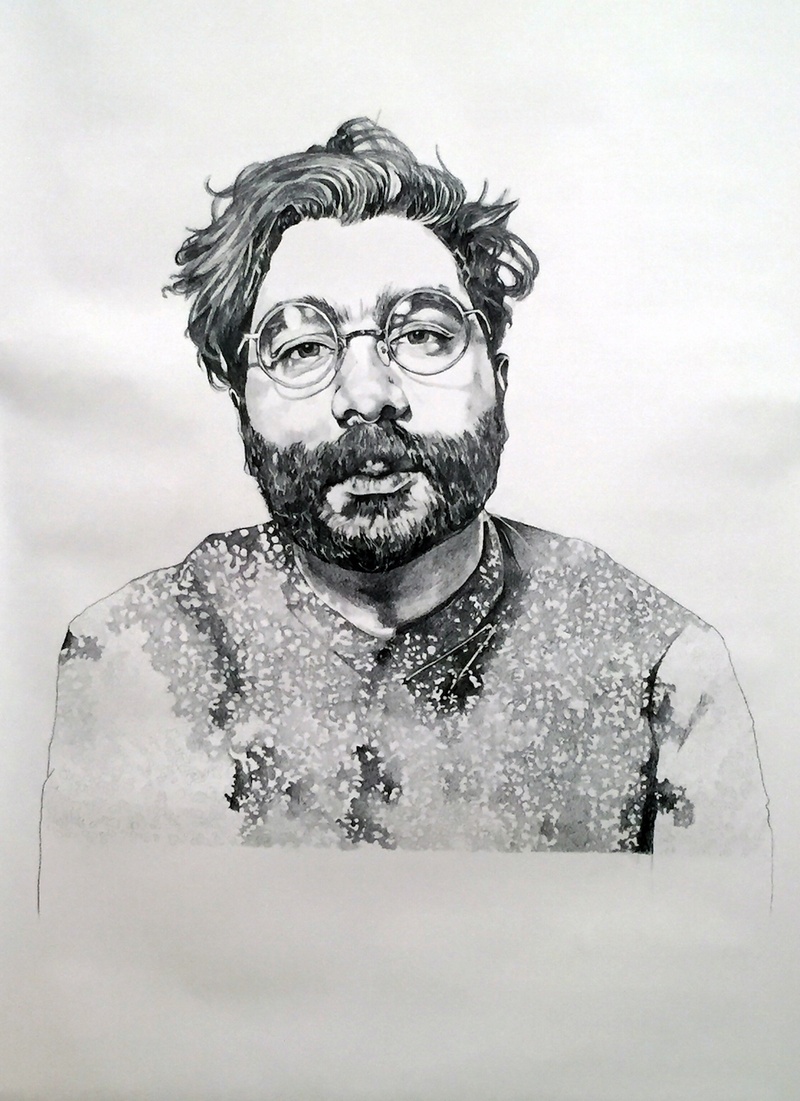

That’s kind of how I got started. My practice has evolved. I initially started primarily as a painter doing large-scale work, 15 feet by nine feet paintings, often self-portraits that explored my experience as a mixed race person, as a trans person, as a disabled person. Then I moved into doing a lot of performance. I started an Activist Love Letters performance in 2012 that I’ve been doing now for eight years that has strangers writing love letters to activists in their communities. I’m mostly known now as a drawing artist, and I make large-scale drawings of people, realist portraiture, trying to reframe portraits around unintelligible bodies, around people at the margins, so I draw portraits of Black activists and trans activists and organizers.

I also have an active performance practice as exemplified by the play Antarctica as well as Ancestors Do You Read Us?, which was the sister project. They are all rooted in my love for science fiction and speculative fiction and storytelling.

Syrus Marcus Ware, Portrait of Thandi Young, 2016

With so many projects on the go at one time, how do you stay organized?

I am definitely somebody who likes to be busy. I like to have a lot on the go, and my brain seems to work well with that. I’m a mad artist, and I think that one of the things that we often hear about mad people is sort of about the struggle and about how difficult it can be to be a mad person in society, but one of the things that I’d like to say is that madness can also be magical and it can be enlivening. One of the things that it has made me be able to be is a highly organized person and I thank my madness for that.

You recently wrote an essay for Canadian Art talking about anti-Black racism in Canadian arts institutions and some of your own experiences. We’ve seen many of these places make statements committing to meaningful structural change. How do we continue to hold them accountable?

What we’re seeing now is the desire for action. The movement beyond statements is what is being asked of us right now. People are saying, “We want to see demonstrative action, we want to see structural change.” So I think for all of the institutions that put out solidarity statements during Blackout Tuesday, we need to come back to those organizations in September, and say “Okay, as you start to imagine reopening and as you start to imagine your next two calendar years, what are you going to do differently that’s going to dramatically improve the life chances for Black artists? Are you going to be acquisitioning them into your collection, building them into your exhibition program, bringing people onto your board of directors, and really pushing them to show us not tell us?” And I think that we need to come back to them every six months and say “Where are you at now?”

The movement for Black life is continuing, and unfortunately the kinds of violence that we see directed towards Black lives will likely continue until we see some radical change in society. So there will be another George Floyd, there will be another Regis Korchinski-Paquet, because the police are a violent system that are out to control and police Black and Indigenous communities. At the next example of Black pain and suffering, what will these institutions do? Will they put out yet another statement? That’s not what we’re asking. We’re asking for action now. So that when we do get to the next next, you have actually started to implement some of the changes we’ve been asking for. There’s been reports, there’s been reviews, there’s been essays, there’s been papers, there’s been studies of all of these institutions around diversity, equity, and inclusion, so we don’t need more research, we need action.

Syrus Marcus Ware, Portrait of QueenTite Opaleke, 2016

I’ve been interested by the way the people have been turning to the streets as their art galleries, as their museums, as their place of performance, as their theatre, because of COVID, because of everything, because of the revolutionary moment that we find ourselves in. We see people literally taking to the streets and painting it in every color imaginable, and doing performative actions, and doing all of these things that institutions couldn’t possibly hold. So I’ve also been very interested by the way that the people are creating their own institutions, their own spaces out in the public, free and accessible for all.

Obviously the pandemic has presented a new set of difficulties when it comes to organizing and protesting safely. What lessons have you and the other Black Lives Matter Toronto organizers learned about adapting to these challenges?

Now is the time to be more creative than we’ve ever been with our organizing and with our activism. We’ve realized you can’t just call 5,000 people together in the same way that we used to be able to do that safely. We just can’t do that because of COVID. You have to think about new ways of organizing that are about distanced spaces and wearing PPE and doing creative activisms that don’t require a lot of people.

One of the things that we’ve learned is this is an opportunity for us to show how we’re going to take care of each other in the future. So when people do go to protests or rallies, and then they go and get tested afterwards and then they self-quarantine until the test results, that’s an example of taking care of each other that we are talking about when we talk about this abolitionist future that we’re trying to get to. Now is the time to practice that; we can practice disability justice by saying it matters that the disabled Black people in our communities survive. The people who are being most affected by COVID, of course, are racialized people; it matters that they survive this , and so I’m going to take care of myself in order to take care of my community after the protest or after the rally. That’s also beautiful to see and witness.

We’ve had to be creative about the way we approach what coming together looks like. As soon as the George Floyd killing happened, we paused for a minute to think about how to do it in a safe way, and our response was to create an orchestrated, organized, 80-person, 7500-square-foot mural that said “DEFUND THE POLICE” in front of police headquarters. That was an art-based demonstration that allowed people to be socially distanced and allowed people to take care of themselves. Then with a partnership with FoodShare, we were able to offer people food boxes, so that they didn’t have to go out to get groceries two weeks after while they were waiting for test results. One of the things that we did was we organized something called Black Grief, which was an online gathering to commemorate what had happened just after George Floyd’s killing and we had different performers talking about their response to the grief that we feel after these kind of police killings. That was another example of an alternative way of gathering that didn’t require people having to be in a shared space.

Syrus Marcus Ware, Portrait of Josh Vettivelu, 2016

What are some of the biggest misconceptions that you hear about the movement?

White supremacy has really done a number on a lot of people, and it has really created conditions where people don’t understand the basic, beautiful idea that Black lives should be inherently valuable. Some of the misconceptions that we hear about the movement is this idea that somehow making Black lives valuable is taking away from other people’s value, and that is absolutely not the case, of course. The Combahee River Collective in 1997 said that when you make the world safer for those who are most marginalized, you are making the world safer for everyone. So when we say “All Black lives matter,” what we mean is that if we actually created the kind of world where all Black lives were considered inherently valuable, we would have radically transformed society enough that everybody would have what they need to survive and thrive.

We’re all activists who are in this struggle because our lives depend on this. This is a moment that is a revolutionary moment. If it feels like we’re in the middle of revolution, it’s because we are—revolution is not a one-time event, it’s a process, and we’ve been going through a revolutionary process. We’re in a period of systems collapse and radical reorganization into a new world. What we’re seeing now is people are starting to grapple with the fact that there are big changes coming, and I’m here for that. That’s what we’re here for, and we need to push for that.

A lot of your work is centered around youth and education. What changes would you like to see made to curriculums and to the education system overall?

I have a Masters in Education, I’m just finishing a PhD, and I teach at the graduate level. I talk about prison abolition and I’m very committed to pedagogy. I really believe in free, accessible public education, and the need to make that readily available to everybody regardless of status and regardless of experience difference. What we need to see is a radical reimagining of our education system as it currently stands—the way that education is chronically underfunded, the way that there are explicit biases in the hiring practices that results in the lack of racialized teachers. I often ask people when was the first time you had a Black teacher? When was the first time you had an Indigenous teacher? And for a lot of people the answer is never, and for some people it might be university before they had a Black teacher.

Just really pushing for the kind of structural changes that would change some of those structural inequities, that would allow there to be a more diverse teacher force able to interpret the curriculum. So I believe the curriculum needs to radically change, but I also believe that you need people who understand and are trained in the content to be able to deliver that curriculum well. We also need to be diversifying our teacher body and diversifying the decision makers, the trustees, as well as the rest of the board.

You’ve co-authored and co-edited several books, including Until We Are Free: Reflections on Black Lives Matter in Canada. How do you approach these collaborations?

I love working collaboratively. Working on a project like Until We Are Free with Rodney Diverlus and Sandy Hudson was incredible because we used a collective approach to our editorial process, and we also knew that Black Lives as a movement is a community-driven movement, so the only way to tell the story about Black Lives Matter in Canada was to turn to communities to tell that story. So we had community members telling their version of what happened, what life in the North is like, what life mothering in the movement was like, what it was like to be Black and Muslim, all of the different things that get covered in the book told by community members.

That was a really important part of this process because it reflected the way that our activism is organized; we are a community-driven group, a community-led group, and we root our work in what the community is asking of us. The whole process took about two and a half years and many, many versions. We knew from the outset that we wanted to root the book in a speculative fiction approach, and so there’s a speculative fiction narrative that is threaded through the book, wherein we’ve made it to the future and we’ve survived and we are free. That’s what opens the book and that’s what closes the book.

I’ve worked with the Marvelous Grounds collective to put out two books looking at queer and trans placemaking in Toronto/Tkaronto, and again, it was turning to communities and saying what are the stories that we have, what are our archives, and then capturing that in book form.

I imagine drawing is very therapeutic, but what else do you do for self-care?

I’m a disabled artist so I really believe in collective care, mutual aid, and self-care. I think it’s so essential to make sure that we stay in the struggle to live to fight another day as activist Tooker Gomberg encourages us to do in his open letter to all activists, where he says to avoid burnout you have to take care of yourself all year long. I garden with my daughter, I laugh and tell stories with friends, and yes, drawing is very therapeutic for me. I find I get a lot of joy from activism so organizing is very enlivening.

I’ve been fortunate enough to work with Elder Duke Redbird for about 10 or 15 years now, and one of the things he’s often reminded us is that the land is perhaps our best teacher, so my way of caring for myself is returning to the land. If I can go and sit by the water, if I can go and have a forest bath, it makes me stronger and able to consider doing more things the next day.

Lastly, I would just say in the early part of the pandemic, I was really captivated by the Nap Ministry, and this idea that for Black people part of our reparations should be our ability to finally be able to rest. I believe in taking naps, I believe in resting, I believe in the importance of slowing down and not just going, going, going, and so I try to remind myself to do that as often as I can.

When did you start DJing and how does that connect to your activism work?

I started DJing in 1998, and I did a radio show on CIUT 89.5 for 17 years called “Resistance on the Sounddial,” it was a show about art and activism here and around the globe. I DJed and also hosted, and I did interviews with everyone from Octavia Butler to trans MP Georgina Beyer from New Zealand to the Marcus Garvey Youth League from Ghana to land defenders in British Colombia. For me, DJing has been a way of helping people to find that experience of Black, queer joy and Black joy, but also a way of lacing through revolutionary ideas. I will often use sounds from the Freedom Archives or sounds from activist archives and weave them into house music tracks, and weave in Fred Hampton and weave in Assata Shakur talking as a way of bringing politics into the dancefloor, I think that’s really important.

What advice would you give young activists right now?

The advice that I would give young activists right now is I would say figure out what it is that you want to change and then just do it. There’s so many jobs that are involved in activism and only maybe one per cent of them involve leading the march. The majority of work in direct action and organizing is behind-the scenes work, and so there’s so much that you can do. If you’re somebody who likes to draw, you can help make the posters. If you’re someone who likes to sew, you can make the banners. If you’re somebody who likes to pick up the supplies, you can pick up the supplies. There are literally countless jobs to do in order to pull any one thing off.

You’ll meet friends through activism, you’ll meet lovers through activism, you’ll meet teachers and mentors through activism, you’ll meet family through activism. It can be such a life-giving practice, but also remember to keep your hand in other things that are fulfilling and life-giving, so that you don’t only have activism as your one center of joy. I really took Tooker Gomberg’s words very seriously about how important it is to have other things that you’re passionate about. So if it’s gardening, garden, if it’s bike riding, bike ride, but have other things as well.

Lastly I would just say as much as possible remember to learn from the past, remember sankofa, remember that we don’t have to reinvent the wheel every single time. I was somebody who in my 20s was full of vinegar, I didn’t always remember that this has likely been tried before, and I could learn from elders to figure out what went well and what didn’t go well, then adapt to the current situation. I wish I had done that more. One of the things that I think is so beautiful about the Black Lives Matter movement is that we have an elders team that we meet and consult with regularly, and so turning to elders is essential to the work that we do. I think that anybody who’s getting involved in organizing, having an elder that you can touch base with is very useful.

Syrus Marcus Ware Recommends:

Octavia Butler and her writing has inspired my practice absolutely. I always take time every couple of years to re-read Parable of the Sower, she was able to predict the now in such a beautiful way even though she was writing in the early 1990s. I also recently re-read Robyn Maynard’s Policing Black Lives and Eli Clare’s Brilliant Imperfection, which is all about disability justice and organizing. I love reading anything and everything by Adrienne Maree Brown, and I have been reading some speculative fiction by N.K. Jemisin.

The artwork of Betye Saar and her Liberation of Aunt Jemima series really had a profound impact on my life and my practice, the artwork of Faith Ringgold, and particularly her series about race riots in the 1960s stands out.

In terms of music, I’m really moved by the work of Sweet Honey in the Rock, groups like Asian Dub Foundation, the amazing Toronto electronic duo LAL. Albums that stand out to me —Mos Def’s Black On Both Sides, anything by Nina Simone. I’ve always returned home to Portishead’s Dummy, because I’m a child of the ’90s and when I listen to that I’m transported to a feeling of being outside time and space, and that is very revolutionary.

- Name

- Syrus Marcus Ware

- Vocation

- Visual Artist, Activist, Educator

Some Things

Pagination