On being surrounded by water

Prelude

As an ocean engineer and an artist, Jane Chang Mi considers the post-colonial environment. She assesses the narratives associated with the landscape through an interdisciplinary and research-based lens. Utilizing multiple mediums, she investigates the land by examining our past, present, and future as we journey towards a technologically oriented society.

Conversation

On being surrounded by water

Visual artist Jane Chang Mi discusses switching careers, quiet forms of protest, keeping a video diary, and collaborating with people outside your field.

As told to Elliott Cost, 2657 words.

Tags: Art, Activism, Film, Process, Collaboration, Beginnings.

I was wondering about your background, as you were an ocean engineer. I’m curious what that is.

I have a master’s degree in Ocean Resource Engineering; essentially, civil engineering as it applies to the coast and/or ocean. A popular or mainstream application would be building a breakwater, to change waves as they approach the coast. Most often to protect the land during storms. In Southern California, there’s one you can see flying into LAX.

In Hawaii, there are a number of structures in and/or near the water. For instance, the Natatorium was a swimming pool in the ocean, near Diamond Head. It’s been closed for quite some time now and is unsafe. Kaimana the baby monk seal actually got trapped in the Natatorium. For my graduate school capstone project we brainstormed solutions, including repurposing the structure. My thesis was on the economic costs of tsunamis if a hundred-year event occurred in Waikiki. So, things like that.

Whoa, that’s really interesting. How did you end up in Hawaii, studying this?

We used to go to Hawaii over the summers when I was little. My grandfather was a waterman, and he missed swimming in the ocean. Southern California waters are cold. I started traveling to Hawaii on my own in high school. For graduate school I went to the University of Hawaii, Manoa. Later, I was also a fellow in the Asia Pacific Leadership Program at The East-West center. I have lived in O’ahu on and off for over a decade.

A lot of my subject matter has to do with critiquing colonization and critiquing the occupation of the Pacific by the American military as well as, previously, the British and French militaries.

When you were working in the engineering sciences, what caused you to start making art?

My father trained as an architect, and my mother studied art history and eventually, library science. If engineering and art had a baby, it would be architecture.

Funny, I was chatting with Alexandra Chang this morning; she is the special projects curator at NYU A/PA. I was telling her about how when I was five, I made these sculptures of boats, including something that looked like a double-hulled canoe. We didn’t have room for them in our house, so my mom had me photograph them. It’s interesting that even today I am exploring similar ideas in my work.

I don’t think there was an exact “a-ha” moment, but after graduating with a master’s in Ocean Resource Engineering, the choices in Hawaii centered around working for institutions like NOAA or for the Navy. Much of my practice now revolves around critiquing this work.

I also knew I wanted to teach because of my family lineage; my grandmother was a dean of a small private school in Taiwan. Education has always been a large part of our family.

Would it be correct to say that you were always making art in parallel to your work as an engineer?

I don’t think I understood what art was until I took my first photo class at Art Center. Where I grew up, there was a woman, Stephanie, who taught art. And so everyone went to her house after school to paint.

This is over-simplified, but I feel like what’s important is understanding and/or learning how we see. And I mean “see” as in all our senses. Feel, touch, and even smell—to be able to consider all of these senses critically. Popular culture seems to designate art as painting or drawing, without an understanding of critical theory. I would say that becoming an artist was defined by this idea.

I think art was always in the background, but my own awareness came after that photography class. And so if there was a catalyst, I would say it was that.

You recently had a fellowship in Hawaii. What was it like to have that kind of support for your work?

The East West Center was established, I believe, in the 1960s by Congress to help facilitate relationships across the Asia Pacific. “Asia Pacific” being somewhat of a loaded term because that was how the American military defined an area, the Pacific theater. To lump all of the Pacific and all of Asia together in that way is a bit odd. Especially, the amount of land, the bodies of water, and the populations the area covers, but it is named that way by the military. And so at the East West Center, there are a variety of programs or fellowships. The one that I completed was called APLP, the Asia Pacific Leadership Program.

I was also the inaugural artist in residence at World War II Valor of the Pacific, e.g. Pearl Harbor. That happened through a number of auspicious meetings, and working on a scientific diving project for the National Park Service at Kalaupapa National Historical Park in Moloka’i. I had the honor of diving in the 75th anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor and the internment of the cremated remains of USS Arizona survivors John Anderson (Boatswain’s Mate, Second Class) and Clarendon Hetrick (Seaman, First Class) to the battleship Arizona.

I was curious about the project where you redrew those photos of Pearl Harbor.

There’s an annual exhibition called Contact Hawaii. It is now in its sixth year. Each year has a different theme. In 2016, the topic was about pre-contact. At the time, I was researching the archive at Pearl Harbor and also at the Bishop Museum. So I redrew the drawings of Pu’uloa. I was considering the landscape before contact. There aren’t a huge number of drawings or etching of Pu’uloa before this. The first published description of the lagoon was in British Captain Nathaniel Portlock’s journal. In 1789, the area was overlooked as the channel was too shallow for Western ships, and only navigable by the swift and smaller canoes. It was not until the HMS Blonde captained by Lord Byron that a survey of the main channel and the three lochs were done by Lieutenant Charles R. Malden. Robert Dampier was also aboard the ship and completed these drawings of Pearl River. The HMS Blonde was returning the bodies of King Kamehameha II and Queen Kamāmalu, who had died from the measles in London.

Views of Pearl River - Dampier, 2016; drawing, 8.5” x 11”.

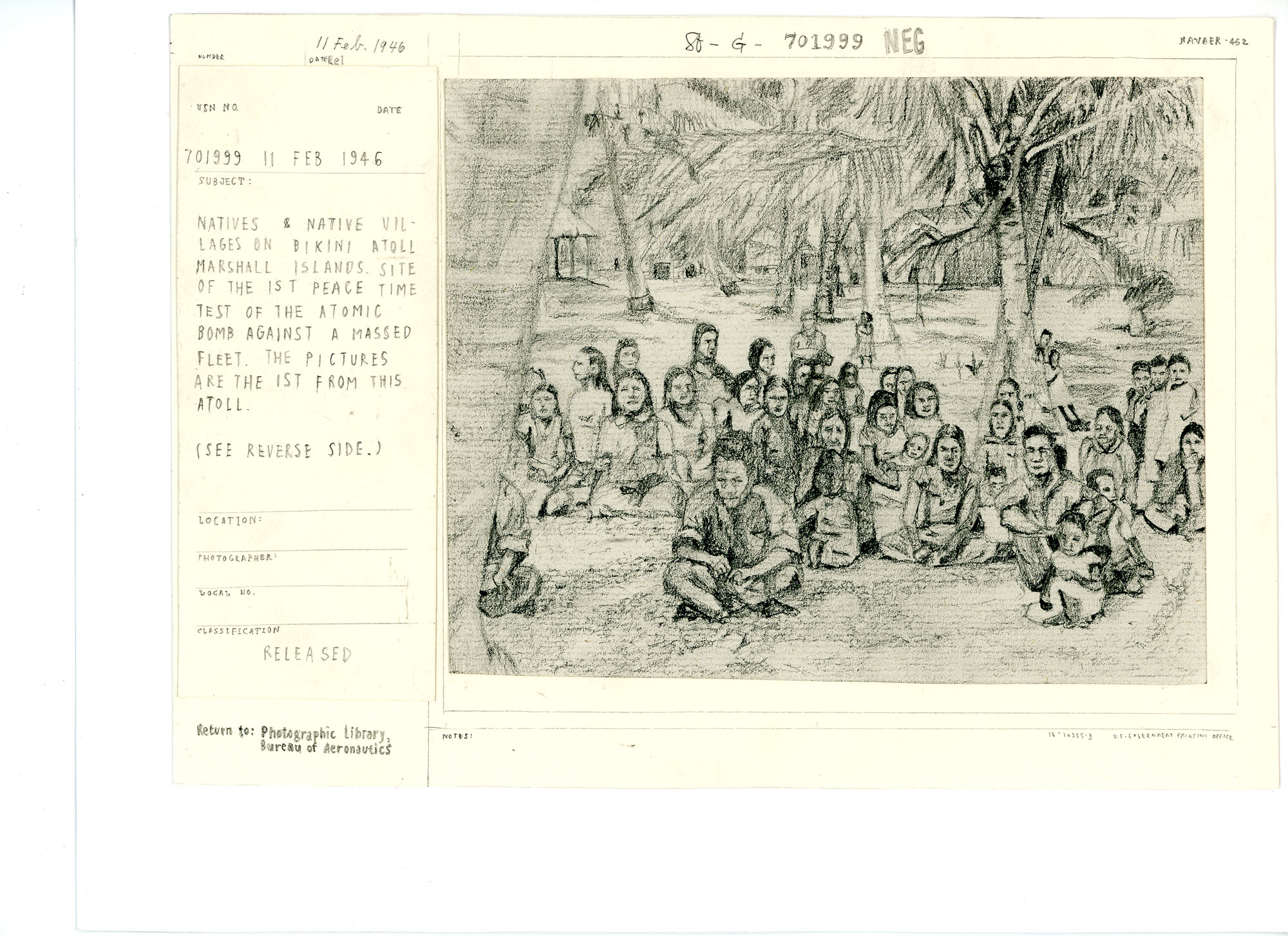

There’s also another body of work that I completed called [See Reverse Side] that considers the photographic aspect of nuclear testings. That is, at the time half of the world’s film stock was used to photograph nuclear tests. Photographs allowed the scientists to analyze the tests. The photographs were quantitative and qualitative, a way of collecting scientific data. The American military wasn’t taking pictures of the villagers, the villages, or the way of life that was being destroyed. Instead, photographs were taken of the nuclear sublime. So I redrew these photographs to highlight the villagers, and their way of life.

701999, 2017; 4 of 18 pencil drawings, 8.5\” x 11\”.

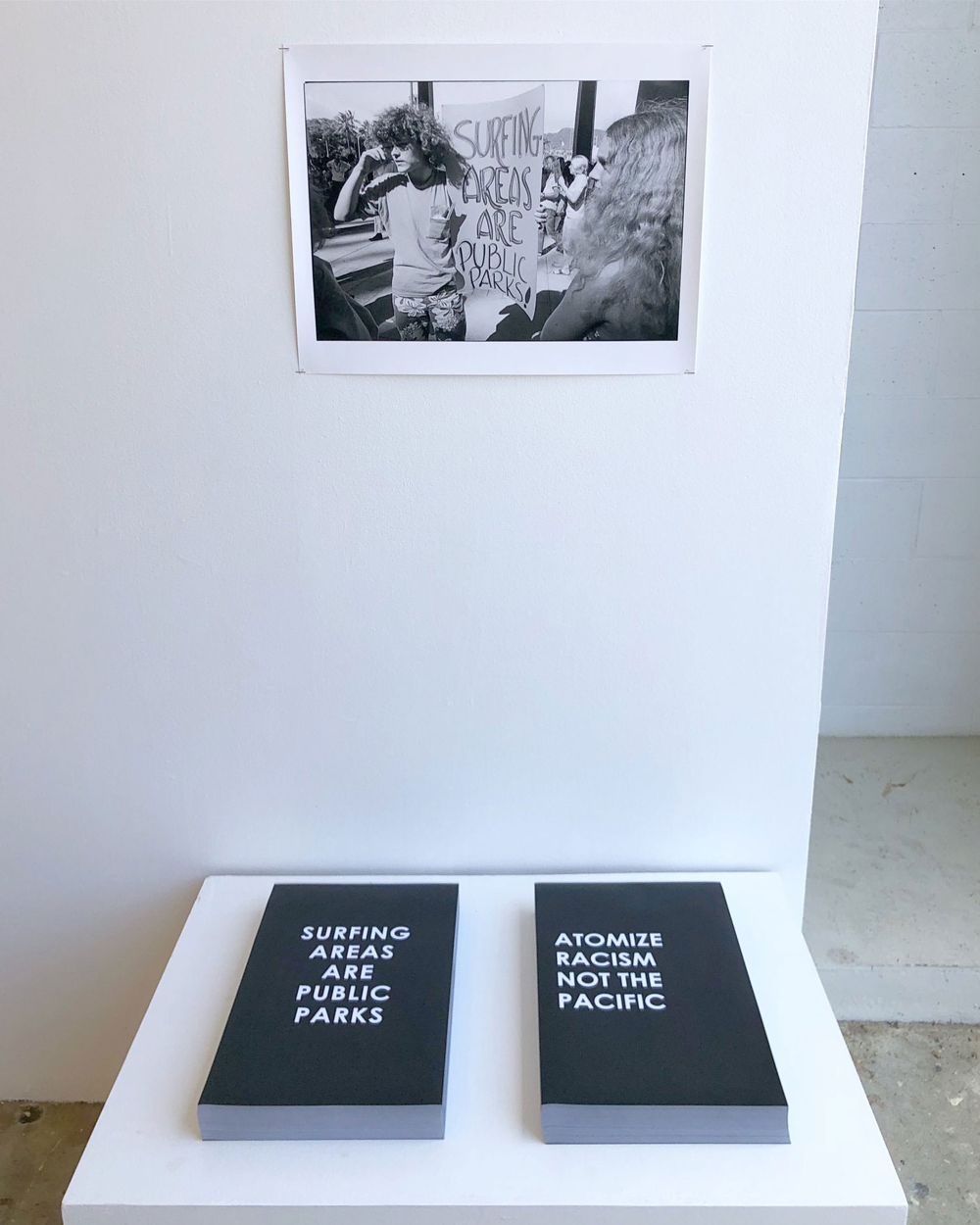

You also recently recreated some signs from archival photographs of activism movements in the islands.

In my work, the conversation between the past, the present, and the future is important. A lot of the protests occurring now are history repeating itself. I have been talking with Ed Greevy for a number of years. I have always admired his photography in both content and aesthetic. So for last year’s project Contact Hawaii, I selected a number of photographs of particular protests and recreated the slogans on the posters. The offset print was made into a tear-able stack with endless copies for viewers to take.

The Spirit of Aloha - Atomize Racism Not the Pacific, 2018; offset print, endless copies. Photograph by Ed Greevy.

Coming from a more technical background, what advice would you give someone who’s coming from a creative field and wants to collaborate with a scientist or engineer? How do you bridge that gap?

A lot of it has to do with community, the people you work with. It’s not about labeling the field that someone’s in, but more about considering the person. Make sure that person’s a good match for you.

100 years ago, art and science were not distinct fields, separate from each other. If you look at Da Vinci, he’s not saying, “Okay, this is science, this is art, and this is engineering.” We’ve only recently separated these fields, categorizing them this way. To be frank, they’re not separate. So being open minded and making sure you work well with your collaborator is more important than determining the designation of what their title is, because their title is just a label.

That’s really good advice. I’m a programmer and also an artist, and I feel they infinitely inform each other. It’s never separate. One of my favorite pieces that you’ve made is this video where you’re floating in the Arctic Sea. How did it come about?

I used to take my camera with me everywhere; it was an extension of my hand. This was before GoPros. The iPhone was also not ubiquitous then. Videos that I made during this period were made on the spot. There’s another work called Throwing Stones, where I literally set down my camera and pressed play. I used to say I became a video artist by accident. There’s another one called Hanami, which has a similar narrative construction with a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Throwing Stones, 2010; single-channel video; 1:32 minutes.

Throwing Stones documents a monk throwing stones at some dogs to keep them away from a sand pile. At first it’s a bit disconcerting, but if you stop to think about it you realize that he probably takes care of the dogs as well. There’s something about his joy about the way he interacts with the dogs.

I was traveling a lot during that time, so making these videos was part exploration, part diary, recording everyday or daily moments. I was in the Arctic through the Arctic Circle Program, and I had wanted to scuba dive, but that didn’t manifest because of the danger of polar bears. Polar bears are avid swimmers. So my project to dive in the Arctic had to be revised, and so I asked, “Can I at least slide down an iceberg?”

Untitled, 2010/2014; three-channel video; 02:42 minutes.

Again, this was before GoPros, so I hung the camera from my neck, as I am sliding down the iceberg. I have a similar work of myself rappelling down a waterfall. I used a GoPro for that one, but it’s hanging from my wrist. I am interested in interacting with nature. We have a tendency nowadays for photographs to be overly romantic and sublime. So these videos are my attempt to playfully get away from that.

I love how close you are to the iceberg. People don’t usually see that—if you’re looking at stock imagery or watching Planet Earth, you never see just a leg and an iceberg. How did you float in that water? Wasn’t it extremely cold?

Extremely cold. I was only wearing a zip-up fleece under my drysuit, not a polar wetsuit. The drysuit was also for kayaking, not for being submerged. So I got cold quite quickly. That’s also one of the reasons why that video is not that long. We had duct taped my sleeves to keep water out. In the Arctic and Antarctic most ships carry survival suits. I used one when I went swimming in Antarctica. The video is not as exciting because I don’t slide down an iceberg. It’s mainly of penguins swimming back and forth. Though even now, I can’t get the taste of penguin poop out of my system.

Wow, that’s wild. I was also thinking of this other video you made where you are just filming the reflection of the Hawaii flag in the water, and Aloha ‘Oe is playing in the background. How was that made? Was there a live band playing it over the water?

No, it’s an older recording of the song. Actually, I recently discovered that Aloha ‘Oe is on the Small World record that I had when I was a little kid. Lately, I have discovered these associations and recollections of Hawai’i and the Pacific that are subconscious, as they were embedded early on in childhood.

Aloha ‘Oe (Farewell to Thee), 2016; single channel video, 03:04.

I was grateful to have unqualified access to Pearl Harbor, while I was an artist-in-residence there. Originally, I was filming a sheen of oil, and then I noticed the reflection of the flag was upside down. It was also right after Trump was elected. So it was quite poignant. The video was this quiet form of protest. It also reflects the ongoing occupation of Hawai’i.

I was just noticing how so many of your works include water. Is there a reason for that?

I am a waterwoman, and so naturally water is in everything. My art practice has evolved and developed along with with my scuba diving. That’s one of the reasons why I had the privilege of being an artist-in-residence at Pearl Harbor. Water is an extremely important element of my life.

Going back to activism, do you see your art or your work as a form of activism?

When people ask this, I point them to my Facebook group called Art in Hawaii, mainly because I feel that the group is a part of my social practice. What’s important is to have conversation. Whether it be discussing climate change or the militarization of the Pacific. We need to pay more attention to these issues. A study was recently published that said fish stocks may be completely depleted by 2040. That’s pretty big deal. Or the amount of plastic we’re ingesting on a regular basis because we haven’t figured out how to recycle.

Plastic is something that was invented and utilized by the military. Men were traveling on boats for extended periods of time, so we had to preserve food. Another example is enriched white bread. Most of these items that we use on a day-to-day basis were only intended to be used in specific situations, but now they’ve been commercialized, and they’re used regularly. We’re not as aware or thoughtful as we should be in our usage. We should be banning single-use plastics. It’s not just for the environment, it’s also just not something that is good for humans as a whole.

Your work seems to be based in a lot of historical research. How do you parse that or organize it, I guess just practically, but also in your mind?

I begin with research. Especially when things are unclear, I will research and write a draft of my ideas. This often goes back and forth for awhile. It’s not linear. My video work is often more spontaneous, but that’s because I have exhausted myself with research. Then it’s easy to point my camera at something, and more often than not it comes together. Overall, there’s a lot of planning, processing, and critiquing before the work manifests in its final form. When the projects are large in scale, there’s a lot of collaborative work with curators and other artists, which also adds to the layers of going back and forth.

Jane Chang Mi recommends

Bookstore: Nā Mea Hawaii (Honolulu) and Basically Books (Hilo)

Coffee: Coffeeline with Dennis

Art Events: Art in Hawai’i

Bars: Bar Leather Apron

Karaoke: Imua Lounge

- Name

- Jane Chang Mi

- Vocation

- Artist, Engineer, and Professor

Some Things

Pagination