On making work to feel seen

Prelude

Jess Scott is a self-taught artist in Los Angeles. She is a painter, illustrator, sculptor, musician, clothing designer, and writer. She currently fronts the band Flesh World alongside Scott Moore (Limp Wrist) and previously played in Brilliant Colors and Index. She co-ran the label Make a Mess, wrote for Maximum Rocknroll, and currently publishes the print-only arts magazine Quinto Quarto Quarterly. She has recently shown work with Tom of Finland Foundation, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit’s Mike Kelley Mobile Homestead, and at her own “temporary, occasional gallery” space, The Staircase.

Conversation

On making work to feel seen

Visual artist Jess Scott on what can be learned from playing in punk bands, forging your own path as an artist, representing queer histories, and creating the kind of work you want to see in the world.

As told to Jenn Pelly, 3065 words.

Tags: Art, Design, Adversity, Beginnings, Inspiration, Identity, Multi-tasking.

You have such a distinct visual language. How would you describe it?

I’ve done paintings on paper, canvas, denim jackets, leather jackets, T-shirts, embroidered baseball caps, sweatshirts, ceramic ashtrays, clocks, faces, pencil holders, matchbooks, notepads, silk bathrobes, flyers, posters, abstract mobiles, light switch covers, lamps, masks, record covers, glass tumblers, retail window stickers, tattoos, logos, publications, and websites. If you can tell that all of those things are by me, I’m so happy. All of that work tries to make joy or fun out of the outermost boundaries of acceptability, or vice versa. I’m constantly trying to make things for a little world of simple pleasure that I wish was there. There’s probably something a little deranged-Disney about it—a great thing about having avoided art school and just consuming Archie, Nick at Nite, and free after-school programs as a youth.

Were you involved with punk as a kid in the Bay Area?

I grew up all over California and moved to Berkeley when I was 14. My parents are divorced and my mom is kind of a hippie. She’s also a lesbian—she took me to Pride in 1990, when I was six. She was involved with ACT UP when I was younger; I remember sleeping in the shirt. I remember there being this sentiment of her having fewer friends, and that was why.

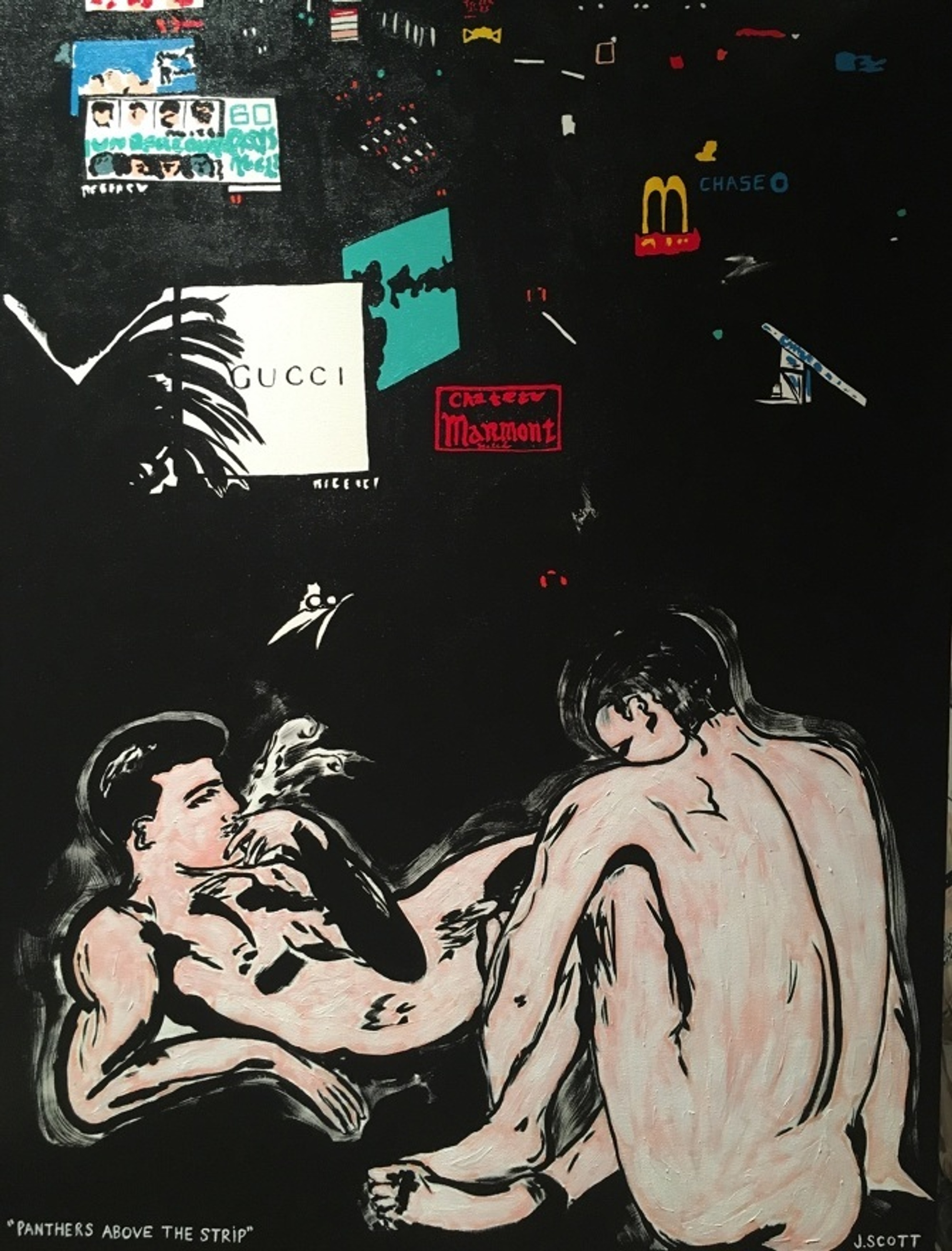

Panthers Above the Strip (2016)

I would hang out at Gilman, but I also had this typical holier-than-thou teenage thing, where I felt like I just had better taste in music than that. Those weren’t glorious times in the East Bay. It was a real Green Day hangover. If you’re getting into punk through Patti Smith and X, like I was, seeing some shit at Gilman is like getting food poisoning. I would be at Gilman to maybe meet some queer people and drink 40s, but I wouldn’t be like, examining the music hand-on-chin. My mom had a partner who gave me the very first Pansy Division cassette, but I explored punk more thoroughly later.

At what point did you realize you were an artist?

Realizing you’re an artist is like looking in the mirror for the first time. You’re looking out of these eyeballs and it’s not really until someone reflects it back to you that you’re like, “Oh, yeah, that’s what’s been going on with me this whole time.” My relationship with my partner Roxanne was a turning point for that, around 2012.

In almost 10 years of playing shows I’ve never made a dollar off my music. My band lives in San Francisco and I live in LA; it’s a pain in the ass. But for every 200 hours that I put into music, there’s like 15 minutes of pure satisfaction that I can’t get from anything else. It could be like 30 seconds during a show, not even a whole song. It’s like a flash.

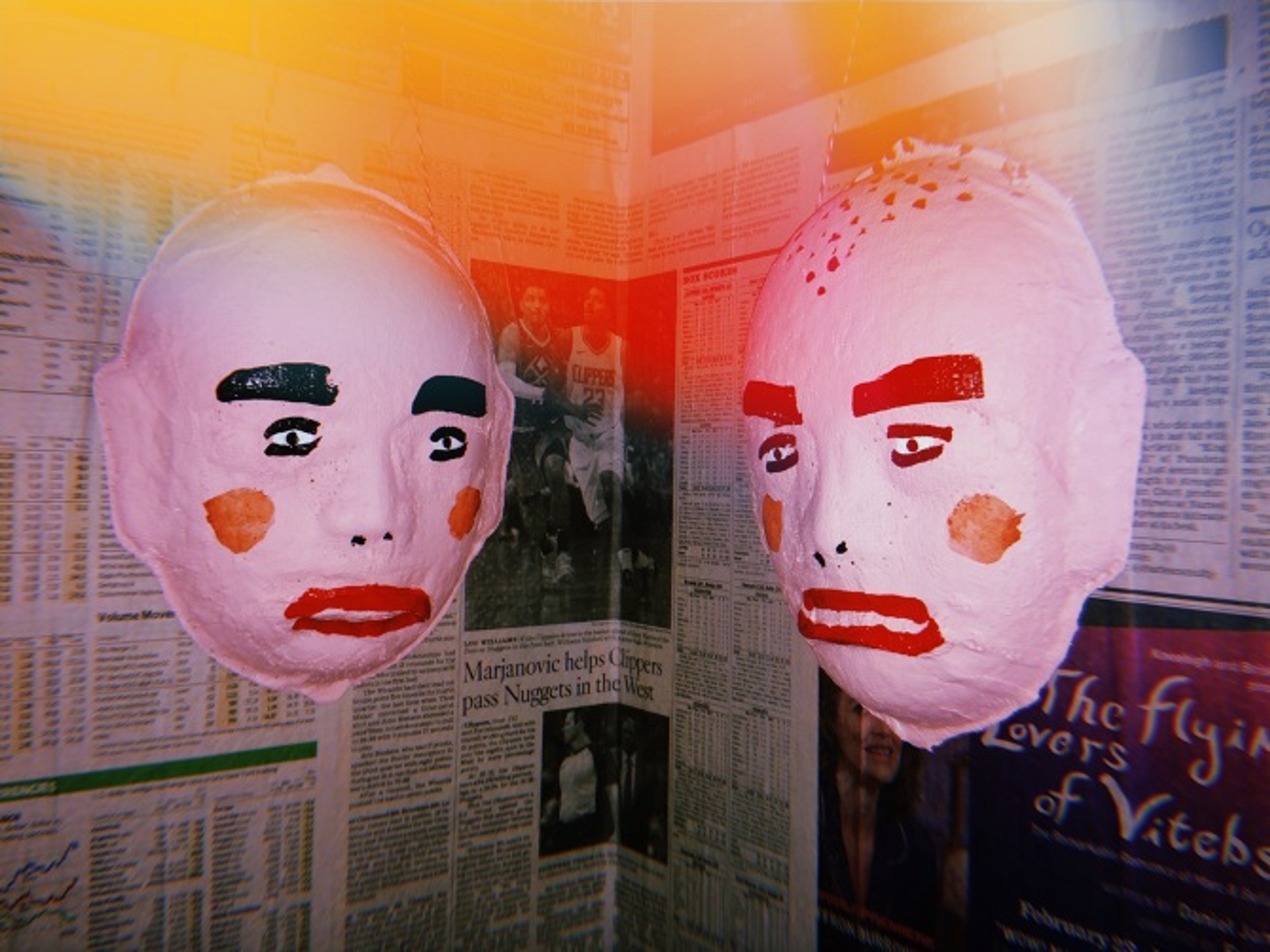

Bust Boys (2018)

Have you ever written a song that you feel complete satisfaction with?

No. I think that’s why I keep doing it. I’m always chasing a song that I’ve not written. There is a perfect song out there.

What has coming from a punk scene taught you about artmaking?

I remember once hearing about a band that never needed to set up a show because they always just got asked to play. That’s cool, but that’s never been my experience in art, or music, or living really. I’ve always had to make something happen in order for anyone to take notice or to get any kind of satisfaction. The first show that my first band Brilliant Colors ever played was in my own backyard. Punk means a lot of things to a lot of different people, but for me it’s been a lesson in not waiting.

I saw Brilliant Colors at [Bushwick punk warehouse] 538 Johnson in 2011 and I knew about your label, Make a Mess. But it always felt like you were doing your own thing. Have you ever felt like part of a community?

I always feel like the odd one out, and sometimes that’s uncomfortable. But it’s better that than feeling like your work is redundant, or like, “What’s the point?” It’s like the rest of me: I’m kind of trying to fit in, but I can’t quite fool everyone.

Brilliant Colors was part of the last pre-Facebook generation of music in San Francisco. The graphic element was so big. I was almost playing shows just to make flyers. I used to make a flyer for every show and I had a route around the city. I would do it all in one day, from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., and talk to people. There was more of a physical community. There’s quite literally nowhere to even hang a flyer in San Francisco anymore. Not to be nostalgic, but I’m totally disengaged with Facebook—I get no satisfaction from it. I don’t know what would have happened today. Maybe I would have lost interest in my music. It really feels like an awkward in-between time in music right now, but you just keep doing it. You don’t know why. It’s not like there’s this giant pay off. You just don’t stop.

The Hideout Altar

You started pursuing visual art in a bigger way about six years ago. What was that process like?

I was only doing flyers until like 2013. I started painting and drawing because I was living in New York for six months and I was pretty lonely. I really did not fit into the music scene in New York. I couldn’t find people to play music with and I didn’t have money for a practice space, I was so broke. I had to do something in my room, so that was it. The first painting I did was on jackets.

I really have come from the outside. I make it a point to go to big, stupid museums that other people don’t care about (like “it’s just all this perfect art made by rich people”). I never fail to leave realizing how imperfect all of that art is—this stuff you think you can’t do. Despite what everybody tells you, there really are no rules at all.

It’s interesting to hear you say that going to big museums is emboldening. I think a lot of people would probably feel the opposite way—that looking at a flyer makes you feel like you can do anything.

Going to the National Portrait Gallery makes me feel like that. All these uninteresting people are controlling everything, and they want you to believe that this is their product now, and you’re like: This is not your product. There’s just no way. I know there’s a lot of corny successful artists, but I believe in more of a Patti Smith approach, like, “These are our people, they belong to us, and it’s up to us to study them.”

“Poolside Boys” is one of my favorite Flesh World songs. It makes me think of David Hockney’s pool paintings. I see blue while listening. How does the act of painting influence your music? Some people hate the word “painterly,” but a lot of your songs do feel that way to me.

I’ve really tried to integrate all these dimensions of myself with Flesh World. I realized maybe I had a few more than your average person singing, or that that’s an important component to try and integrate. It would be such a waste to act like these two things, music and painting, aren’t related. I saw this exhibition of David Hockney at the De Young and I felt like I saw things literally differently afterwards. Everything was really on fire. I felt like something opened up in my eyeballs. I wrote the lyrics to that song around that time.

Some people don’t think it’s important to talk about their influences, or think it should be a secret. Whereas I think if you read this woman I’m writing about, or look at this painter, you’ll get more where I’m coming from. I guess they’re breadcrumbs, trying to create things like a collage. I really don’t care about lifting or mimicking. I can’t copy a face and have it look like an actual face; I can’t write lyrics like anybody else. I have my own way of messing things up.

I’m interested in the ways that what people do physically impacts the way they write or create. How the actual act of painting or drawing might impact the way someone makes music. I’m a huge Arthur Russell fan and I’ve read about how when he was in California, he practiced cello with a teacher who was into kinaesthetic approaches. She would say: “If you want to be an expressive cello player, then paint a wall, or move buckets of water around, because those are expressive actions. Channel that feeling.” It makes me think of how the actual act of painting and drawing might influence your playing.

If you look at my images and my music, there’s a personal, idiosyncratic, figurative approach. And I’m making three-minute pop songs. It’s the same muscle in my mind. I’ve never been about reinventing the wheel. I just want to figure out how I can make everything in my head fit into something that somebody else might understand. I always try to allow multiple ways in. There’s almost nothing that I’m prescribing. A painting might look queer to a queer person, or it totally could not. My lyrics never refer to gender. I really like there to be an openness.

Flesh World has a song called “This Great Cheap Face.” I noticed that phrase in the oral history of writer/actress Cookie Mueller, Edgewise, and your song references Cookie directly, too. How has she influenced your work?

I wept literal tears throughout the last 30 pages of that book. She’s just one person that we barely know about—underrecognized, not paid, dead, like the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier. But I had a complex, crazy reaction to [Edgewise]. It’s like being obsessed with the Beatles—it’s not about the Beatles. The Beatles are just this symbol of classic 20th century emotion. People become symbols of things you’re feeling inside. Cookie is like that for me.

Jess Room in Tom House (2018)

Something I love about that book is how you have this constantly shifting opinion of her. She’s far from a perfect person. And there are people who like her, people who don’t, there’s a lot of catty people. “She had this great, cheap face” was this perfectly backhanded compliment. I wrote that phrase down when I read it; I keep a little list of song titles that I can write lyrics to. I was really laughing that someone had the balls to say that about this revered dead artist in a biography about her. It seemed like a good reminder that people, especially women artists, are just put through the same shit over and over. Somebody could say that two years ago, 30 years ago, 100 years ago, it’s always the same. I also found it to be funny. So that’s sort of my split personality.

It captures the imperfect beauty of someone, which is really human. Cookie acted in John Waters’ films, and I noticed a lot of your flyers have the quote “I’m your sister in crime” from his movie Desperate Living. You’ve also collaborated with him—what was that like?

He does a two-show residency at this club in Detroit every year for his birthday. I was asked to do an art show for it, and I did these paintings that were like surreal reinterpretations of his incredibly surreal films. His dialogue is underappreciated. It’s an understatement to say he could have gotten by on stand-up comedy alone. He was always sort of around when I was growing up. One of my first flat-out obsessions as a kid was Hairspray.

How else did he change the way you think about the world?

It’s related to humor. That’s part of what draws me to Cookie, too. You’re laughing out loud about a horrible situation. A lot of stuff in life is terrible, things are bleak and disgusting and dirty, but it’s up to us to see: “Oh, this part of it is kind of funny.” I just love not having a direct way in or out of subject matter.

You tend to draw and paint male bodies. What attracts you to that?

I find it really easy to practice mathematical-ish, art-perspective things on guys and not worry about how they look at the end—because I don’t really care. It’s like still fruit. I want gay men to buy my art.

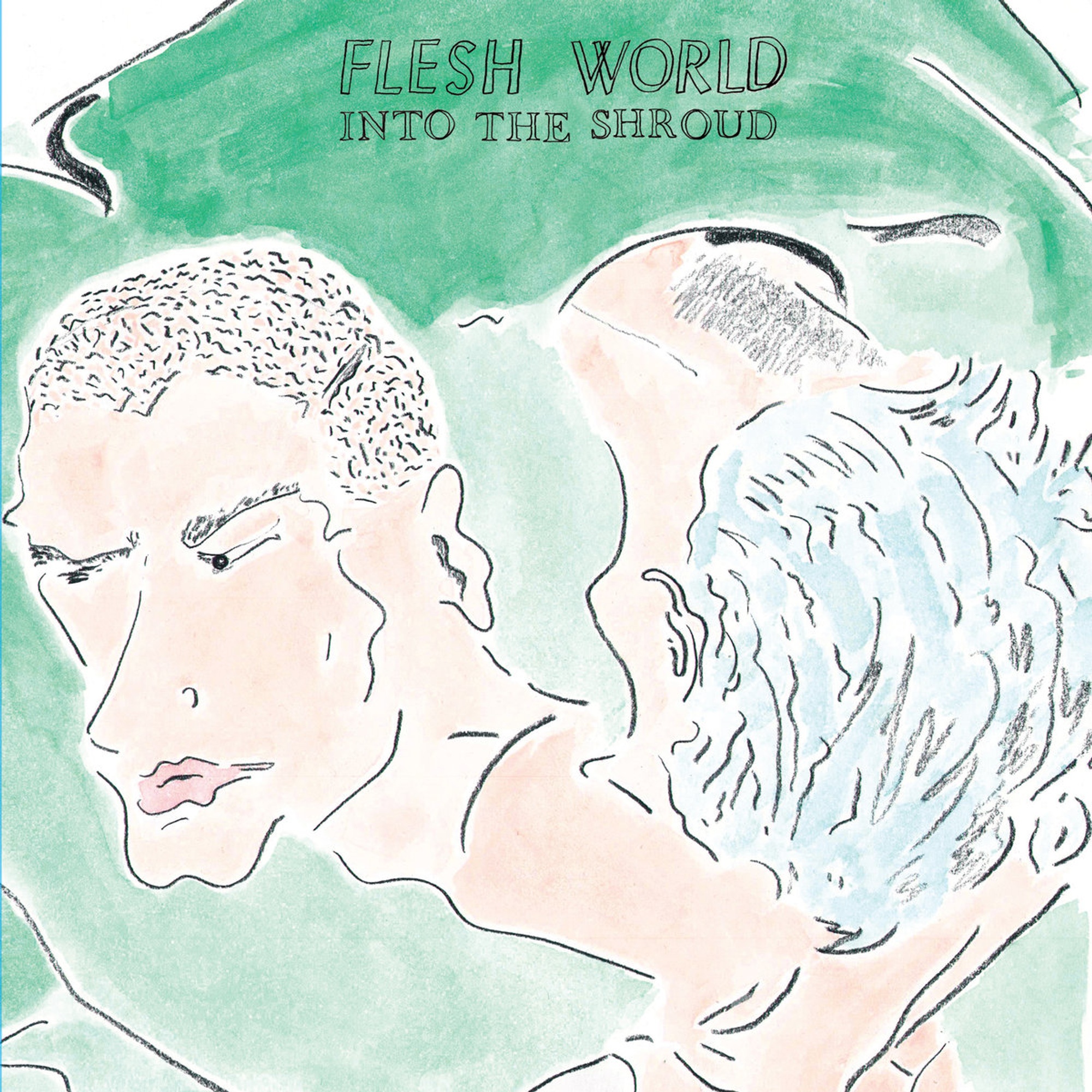

Flesh World, Into the Shroud album cover (2017)

Their facial expressions are so evocative, emotional, and contorted—like the figure on the cover of Flesh World’s album Into the Shroud. What do you want them to evoke?

I’m always striving to make an imperfect image. I never have identical eyes. People are really freaky looking, even conventionally attractive people. People are weird, perspective is weird, angles are weird. I’m always trying to capture that in my self-taught way. I’m always trying to convey something that isn’t really there. Somebody else can show it perfectly. There’s a load of ambiguity in that cover. It’s from a phase when I was doing a lot of figure drawings. I was ripping from pulp books I have around the house or online. There’s a lot of guys at weird angles in pulp stuff that I’m always trying to learn from—exaggerated and comic-booky, but also painterly.

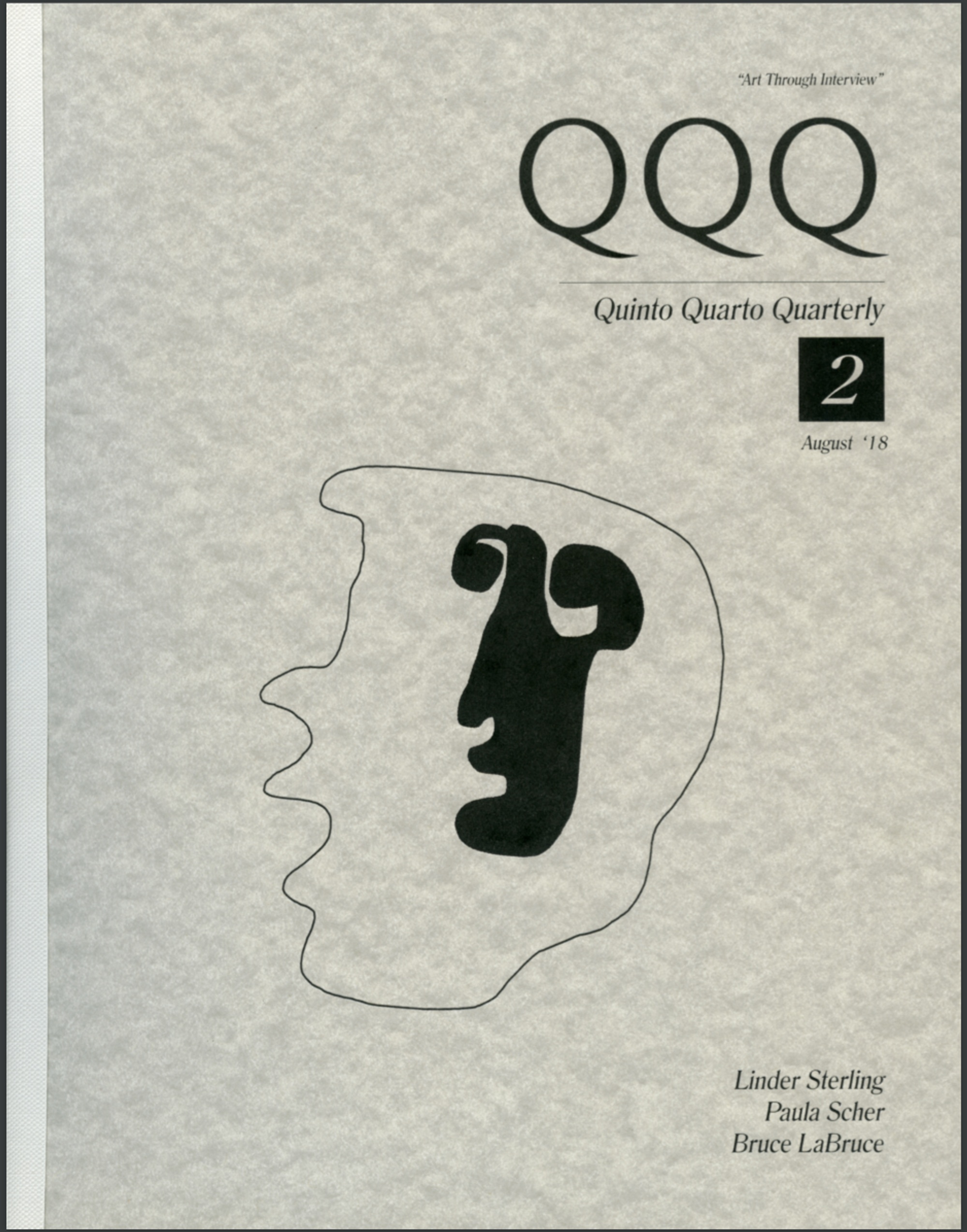

In 2018 you started a quarterly print-only arts magazine, Quinto Quarto Quarterly. What inspired that?

It was an impulse. I don’t know why I’m doing it except that it’s something I wish I had around to read. I felt that there was a gap in who I wanted to read about, how it would look, how much it would cost, how frequently and democratically it would come out, and how unpretentious it would be. Art books are obviously a racket, but there’s a lot of satisfaction on the lower-end of investment as well: the cheap paperback can be so gratifying, just as the little $5 major-label financial flop can be.

So far you’ve interviewed Genesis P-Orridge, William Basinski, and Linder Sterling, among others. What are some criteria for an artist you would interview in QQQ?

I want them to have a history that is difficult to explain. That’s when I know there’s a whole conversation to be had. I also cringe about mass-interest driving a lot of content online, i.e. the tyranny of the general public.

Quinto Quarto Quarterly cover (2018)

In each issue, you’re pairing three interviews with photographs of incidental materials from the artist’s life. What do you hope the effect is?

I hate taking press photos and I assumed it stresses other people out, too. Those photos end up being pretty boring to look at most of the time. I want the dirt, the imperfection, the stuff that is entirely too incidental to make it into a magazine or website—their silly little Post-It note or weird fan mail or ripped-up poster on the inside of their closet door. I want to get a full, deeper history out there in an economical, instant way. There’s a Warhol time-capsule aspect to it. I’m interested in the everyday life, not because I think “we’re all the same at the end of the day”—these are exceptional people—but the value is raised then on what constitutes the everyday.

The new issue of QQQ has an interview with Bruce LaBruce, and your work in general seems to very discernibly honor queer countercultural history and lineages. Is that intentional? Is it important to you to acknowledge overlooked predecessors in your work?

It is so unintentional, but then again so is my being gay! Sometimes it feels like one of those little guides to identify a plant or a bird: I follow these steps towards the artist who interests me and I turn the page and whoops, they’re queer. But I led myself toward them through substance and I think that is something that needs to be flexed especially now. I think there is still a very long way to go in the ways we document culture. I don’t think the progress is linear and each generation gets itself in a little drunken stupor about what’s going to create real lasting change. There has to be quality in the document to record a community’s history, and I hope maybe QQQ is a little token toward that.

Do you have a day job, and if so, how do you find the time?

I have always had a day job. I run an archive for the estate of a famous person’s family. I think this is where I’ve been able to hone my snoopiness, and that has informed wanting the incidental materials in QQQ. I have struggled to allow myself to work four days and not five days per week, which is an essential, practical alternative to what seems like a “work week” written in stone. I highly recommend having a studio to run away to.

What makes something beautiful to you?

I just want to feel spoken to. I don’t relate to almost everything in this world. So when I find something I do relate to, that’s beautiful.

Jess Scott in Jess Room. By Ringo (2018)

Jess Scott recommends:

“list for proof there are no rules in museums not even in the past”

- Luis Camnitzer

- Eileen Agar

- Rosalind Bengelsdorf

- Milton Avery

- Alexander Maldonado

- Sophie Taeuber

- Joan Brown

- Albina Felski

- Equipo Realidad

- Jack Smith

- Annea Lockwood

- Donald Rodney

- Cocteau

- Picasso

- Maya Deren

- Name

- Jess Scott

- Vocation

- Visual artist

Some Things

Pagination