On following a non-traditional path

Prelude

Julia Maiuri (b. 1991, Michigan) currently lives and works in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She received her MFA from the University of Minnesota, Twin Cities (2022), and her BFA from Wayne State University, Detroit (2013). Her work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, with recent solo exhibitions at Make Room, Los Angeles (2023) and Gallery 12.26, Dallas (2022). Maiuri’s work has been featured in group exhibitions that include Fredericks & Freiser, New York City (2023); Make Room, Los Angeles (2022); Klaus von Nichtssagend Gallery, New York City (2022); MAMOTH Gallery, London, UK (2022). Her work has been featured in art publications such as ArtReview Magazine, Artsy, Visual Art Source, Art Maze Mag, Floorr Magazine, and WOPOZI.

Conversation

On following a non-traditional path

Visual artist Julia Maiuri on the magic of painting, the value of having a day job, why the Midwest matters, and learning to say no.

As told to Claudia Ross, 2161 words.

Tags: Art, Education, Money, Process, Identity, Day jobs.

Could you talk a bit about your use of film noir stills? What drew you to that source material?

I grew up hearing true crime stories: my mom was a big true crime person. So detective mysteries were always of interest. I wanted to explore that early period of the crime genre in film noir because I was interested in where the contemporary tropes come from.

I felt like I became an amateur sleuth myself because I was trying to connect these dots between time periods, and I became really interested in the connection between film noir and the postwar period—there was a lot of disillusionment happening in American culture specifically, and that bleeds into film noir.

I feel like we’re in a similar period of disillusionment, especially in the last few years. True crime is such a huge trend right now, too, so it seems like there’s something in the culture that responds to similar stories. There’s an anxiety that I want to probe further.

I like your idea of the painter as a kind of sleuth—a detective. How does that manifest in your artistic practice?

I think making art feels like problem solving. Sometimes I have to try a composition several times before it finally feels right. There’s a lot of trial and error before I finally land on it.

And leading up to painting, I make a lot of digital collages. I watch the movies on my computer and take screenshots–then I catalog them all in different folders. I’m like that meme of Charlie in It’s Always Sunny. When I finally find that image that completes the composition, it does feel like I’ve solved this mystery. It was there all along, but I had to dig deep to finally figure it out.

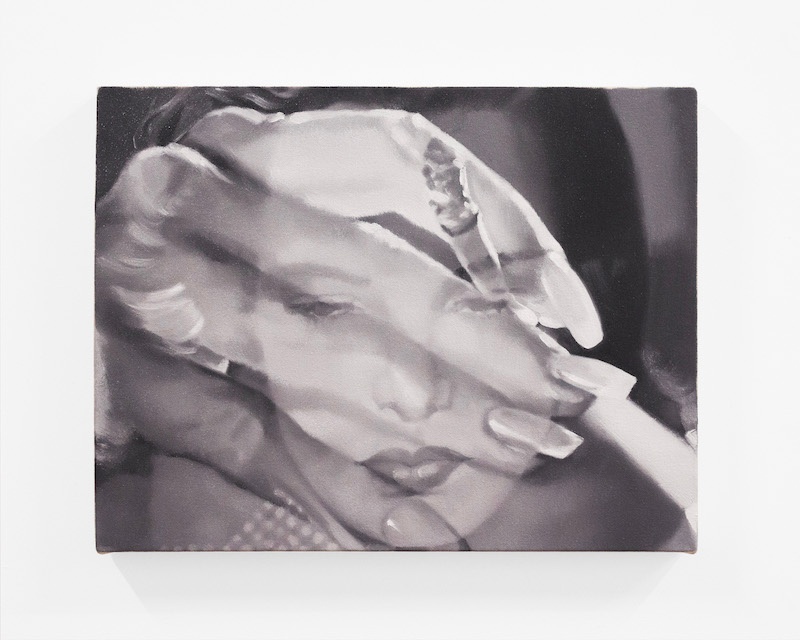

Dinner Party, 2023, 16x12 inches, oil on canvas

Is there a point where you abandon the digital workflow in order to focus on the painting? Is that a conscious shift for you?

Once I’m painting I’ll be in a flow, and I’ll only look at the computer to make sure what I’m doing maintains its relationship to the source material. But I think that the process of painting does change it a little bit. They will look different when they’re side by side. And I’m okay with that, too.

I like to get lost in the feeling of alchemy that painting naturally has, where there’s a magic happening between what’s going on in your brain and what’s happening on the canvas. So I do let go a little bit, and that’ll come through in the brush strokes, the color scheme.

Sometimes, too, I’ll think that it works in a digital collage, and then when I try to paint it, I’ll realize that something is missing. For every painting that actually happens, there are six or seven digital collages that didn’t work.

When do you decide to abandon a painting?

I only spend one session on a painting because I work wet into wet, so I always know by the end of the day. Once it dries a little bit, it’s harder, and I have a really hard time working back into it.

Sometimes I’ll ask for feedback, but usually it’s up to me. People might tell me, “Oh, that looks good. You should keep trying it.” But I already know it’s over. I have to move on. I’m pretty quick to just discard and start over.

I think part of it is the excitement in the moment, too. If it’s not exciting in the moment or I’m not getting there, then the way I find excitement is by starting again and figuring out a new entry point.

Confessions, 2023, 14x18 inches, oil on canvas

So there’s this preparatory work that you do, sourcing imagery and composing it online, but then the actual moment of painting is very instantaneous and intuitive.

Yeah. Prep work helps me get into the flow quickly, too, once I get to the studio. It also gives me something to do at home. I don’t really do any of the digital work at the studio. That’s strictly painting time for me, and I usually know within a couple of hours if something is working or not.

Are there certain things that you do in the studio to help cultivate your practice?

I have rituals that I do when I get to the studio. I know some people have couches and nice lounge areas, but I don’t have that. I have one really uncomfortable chair that I sit in. I always have food on hand, and lots of water and coffee.

Since I only paint at the studio, I think that makes it feel special, too. The studio is my retreat from my daily life or my home life. Having the studio as my designated painting space helps it stay sacred.

I know that you work in St. Paul in the Twin Cities. How does that influence your practice? Is it important to you to stay in Minneapolis?

I’m from Michigan originally, in Metro Detroit. I’m such a Midwesterner. I just get it here. I understand the pace. And it’s easier to find studio space for more affordable prices, although the Twin Cities is getting more expensive, but it’s still way less expensive than a coastal city.

Growing up I was always hyper aware of financial issues in my family. It’s embedded in me that I need to save money, and that I need to find a place that’s affordable to make my practice sustainable, to feel secure.

It also feels like it’s not necessary to live in [coastal American cities], especially with social media and Instagram. That’s been my main way of connecting with people. I think even if I did live in one of those places, I would still have a hard time meeting people. I am naturally very introverted and it’s hard for me to branch out socially. I feel safer on the internet.

How do you see your Midwestern sensibility reflected in your work?

I think my work has a voyeuristic quality, and I wonder if that’s part of my temperament from growing up in a “flyover state.” There is this feeling I have of being an outsider and looking in, spying on a part of culture that is very visible but that I’m not necessarily welcomed into.

I grew up mostly in trailer parks. I lived in one house for a couple of years, but then moved back to a trailer park. There’s a lower middle class angle to my Midwestern existence that feeds into my attempt to interpret things that are happening in America, while my own backyard is not necessarily paid attention to.

And that relates to my interest in David Lynch and Twin Peaks. In Twin Peaks, things may appear nice and wholesome, but when you peel back the layers, you start to find something else—something unsettling, mysterious.

Are there certain emotions or moods that you’re interested in portraying?

I think I’m mostly interested in creating tension, and that comes through in these images where you’re not really sure if we’re moving into the future or going into the past. But I don’t think I’m interested in nostalgia necessarily. I’m not interested in representing sadness or fear, which maybe you think of in horror or noir. I’m more interested in uncertainty.

I watch a lot of older movies, so I’m always finding a balance between their time period and the present. I don’t want it to come off as nostalgic. I want my paintings to show that there is something about this image or story that is persisting through time. How do we relate to the past and learn from it rather than romanticize it?

I was looking at some of your older work, and I noticed that there was a lot of natural life. There’s insects and bugs and spiderwebs.

I think I was starting to do that more in grad school when the pandemic started and I was stuck in my apartment and we kept having these carpenter ant infestations. It felt like my apartment, the place where I’m supposed to feel safe, was being corrupted by bugs and by COVID. There was this transgression happening in the domestic space.

In painting figures, I want to represent reality in a way that feels dreamlike and disjointed. There’s still a sense of uncertainty, where you’re not really sure where you start and another person begins. And that also coincided with going back into the public and being around people again.

I am always working out something unconscious in the paintings: how I relate to people, how people relate to me, how I relate to the culture and how I relate to the past.

Curtain, 2022, 8x10 inches, oil on canvas

How did your MFA help you? How did it not help you?

University of Minnesota was the only program I got into. I got rejected by so many programs over and over again. I applied multiple years. I got in [to Minnesota] off the wait list, which bruised my ego more than anything. It took me a couple months to think, “Okay, I actually deserve to be here.” But it was a really great program. It’s fully funded. I had to do a TA-ship 20 hours a week, but I was used to working 40 hours a week.

It’s also a really big university with so many outside art classes. One of the best classes I took was a Scandinavian horror class. So we watched all these horror films and got to talk more in depth about the genre, which really informed my work now.

The one thing, too, and I think this is an issue across art schools, is that I didn’t actually learn the business side of art. I had to figure that out myself. How do I file taxes? How do I track expenses? What does that look like? And how do I work with galleries? It almost seemed taboo to bring up. I just had to learn on the fly.

How do you juggle professional obligations with your creative practice?

I’m trying to give myself time to really experience things and not make impulsive decisions, because it can be really exciting to be offered an opportunity or a show. For the last year, I’ve been saying yes to so much. I overloaded myself. So now I’m like, “Okay, what could I maybe say no to?” I’m learning that I can say no to things, and that I can really think more about what context my work is in.

I’ve spoken to a lot of painters that have day jobs or night jobs. Is that also something you do to supplement your creative career?

I’ve always had a job on the side. I work better in the studio when I know there is some stability. Right now I only work a couple hours a week, so my full-time job is painting, which is really nice. But you never know when your paycheck’s going to come through from a gallery, so I feel much better knowing I have a small amount of money coming in every couple weeks from this regular job.

I work at an art supply store. I get a discount, which is really cool. All my coworkers know everything there is to know about every art supply that you could possibly buy. I probably spend a lot of my paychecks just on buying paint and stuff, but one of my bosses bought a painting of mine from my show at Make Room. It’s been pretty nice to have that in my back pocket as another support system.

What’s your perfect creative day?

I would love to wake up early and not stare at Instagram on my phone for the first hour. I would get up and just get straight to the studio. I’d be perfectly hydrated. Then I would make a painting that I’m very happy with. And then I’d come back the next day, and I wouldn’t hate the painting.

Julia Maiuri Recommends:

Looking at pictures of tortoiseshell cats on the r/Torties subreddit

Allegra non-drowsy gel cap allergy pills (must be the gel caps) so you can survive the changing seasons (and get a tortie cat that you are allergic to)

Biena “Lil’ Bit of Everything” crunchy chickpeas

Watching the movie What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) and everything about the making of it

Remembering, 2023, 6x4 inches, oil on canvas

- Name

- Julia Maiuri

- Vocation

- visual artist

Some Things

Pagination