On being inspired by the everyday

Prelude

Sable Elyse Smith is an interdisciplinary artist, writer, and educator based in New York. Using video, sculpture, photography, and text, she points to the carceral, the personal, the political, and the quotidian to speak about a violence that is often unseen, and potentially imperceptible otherwise. Her work has been featured at MoMA Ps1, New Museum, the Whitney Museum, The Studio Museum in Harlem, JTT gallery, the Venice Bienniale, and numerous others. Smith has received awards from Creative Capital, Fine Arts Work Center, the Queens Museum, Skowhegan School of Painting and Sculpture, Rema Hort Mann Foundation, the Franklin Furnace Fund, the Joan Mitchell Fellowship, Louis Comfort Tiffany Foundation, and Art Matters. She is currently Assistant Professor of Visual Art at Columbia University. Smith’s first solo show at Regen Projects, Fair Grounds, presents a series of two new sculptures and several “coloring book” paintings.

Conversation

On being inspired by the everyday

Visual artist Sable Elyse Smith discusses working through intuition, finding inspiration in the people around you, and embracing your history.

As told to Katy Diamond Hamer, 2187 words.

Tags: Art, Identity, Process, Inspiration.

In your practice you are so candid about your personal experiences with a father who has been in-prisoned. This narrative is a catalyst for much of your work and observations. Can you talk about what it means to find “home” or comfort in objects?

It’s an interesting starting point. Questions or concerns that you bring up—one being absence and the other connection. I’m paraphrasing but I am thinking about emotional connection. There is an emotional experience and an emotional intelligence that can be a way to bring people back to the center. It’s a gross generalization, but in art we talk about an object, which is distant and separate. Then there are all of these movements or genres that are all about emptying out—emotive and [looking at the] facts of what it means to be a human being. I think that’s a difficult concept for me to think about because that is what the world is. How do you talk about the world without actually locating us in something that is felt first? It doesn’t have to be the only thing, and it isn’t the end of the conversation, but I do think it’s the foundation of the conversation that I’m interested in having. I can talk around that.

Sable Elyse Smith, BARRICADE, 2023, powder coated aluminum, 41 7/8 x 53 x 53 inches (106.4 x 134.6 x 134.6 cm)

Another thing you point out, which is actually really important to me, is how I’m focused on observing everyday objects or what some people might classify as inconspicuous. How I’ve come to think about and know art and artists is not in the intellectual or academic way that we’ve become familiar with in the art world, but through all the people around me that were doing something creative. They were putting two objects or ingredients together to create joy, excitement, to help someone in their process, to bridge a gap, or to find closure through objects and gestures. This has always been the most important art for me, and those [who engage in this type of practice] are the most important artists even today. I’ve grown to like some [contemporary] artists, but there are so many different contexts or anchors for conversation.

How has writing played a role in your thought processes?

I tend to be a very quiet person and am very interior, so early on, writing was usually my main outlet and something very important to me. It requires keen observation and attention to detail. If we think about some of the greatest fiction writers, when they are describing an environment that is usually relational between humans, through the objects they are surrounded by, the colors, the humidity in the air. These are the ways that we can get to something so complex, or heartbreaking, or difficult to articulate and find language around. So my practice has always felt intuitive and a natural to look and research what is happening in spaces. Because that is what I am intuitively drawn to, I start to look at that framework more rigorously.

That is beautiful and something that I’ve immediately felt with your sculptures. You aren’t necessarily changing the source (table, chair, etc.), but rather giving it a new otherworldly, geometric form. How did you arrive at the shapes you make in your sculptures?

It’s nice that you bring up the question of use and value. I try to provide a broader framework for things that I’m interested in. Often those things get reduced to the thing that feels…I don’t know, the most salacious or glaring —prison, power, violence and violences. I’m not actually interested in creating an image, caricature, charge or to recreate a picture of violence. By taking an object, which for all intense purposes is a seat and a table, that has a capacity to exist, that should exist, but this specific seat and table were designed for one specific environment, a prison visiting room. I think of its use-value which is very different for us, the “free” and how we experience the necessity of this furniture object. Its use is a violent act. There is violence implicit in the existence of it in that context and shape around it but that is not something that a general audience or general population would look at as violent or even be able to wrap their heads around.

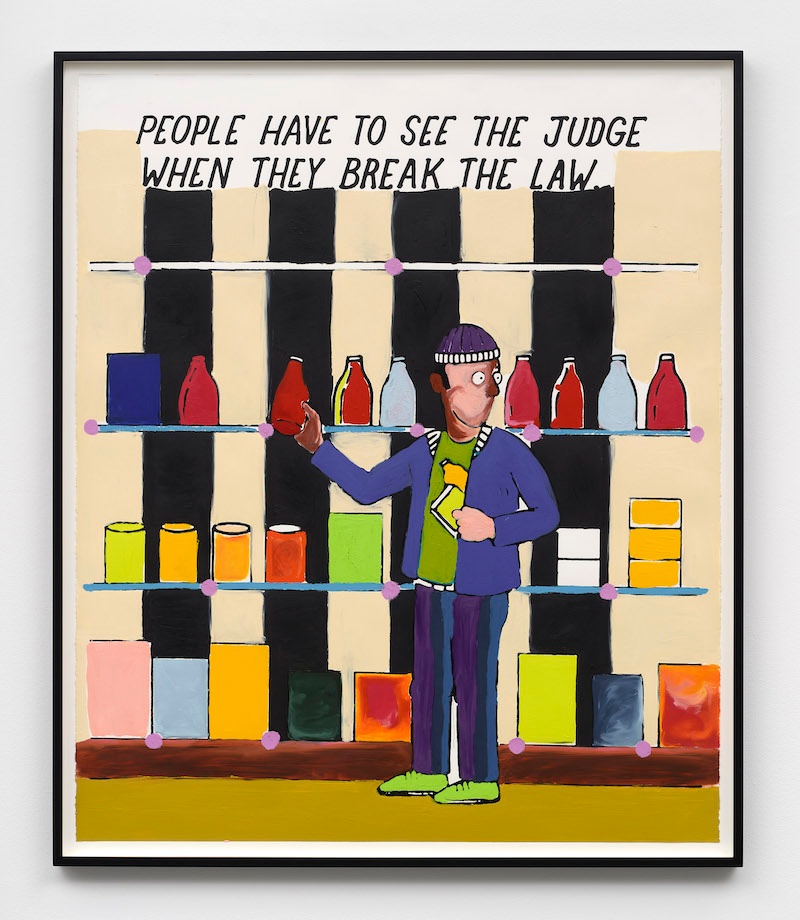

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 140, 2023, screen printing ink, oil pastel, and oil stick on paper, framed dimensions: 63 1/4 x 53 1/2 x 2 1/2 inches (160.7 x 135.9 x 6.4 cm)

I’ve had many different types of conversations with people and still there can be a gap in comprehension. It’s a difficult reality to process. This is also something I’m interested in and why it felt kind of natural and immediate to think about the prison visiting room space. So many things that happen there—images, symbols, narratives. There are a million possibilities that I could make about that space. The objects that I present are legible but also have an illegibility. There’s a time-scale for them to come into focus. Thinking about that kind of time, the slowness of reading an object, this was inherent in how I thought about how I wanted to manipulate it or why to present it in the first place.

In all the series of works or mediums I’ve used thus far, I think the thing that is most interesting is to find something that already exists and speaks to a structure or system that we are already living in but is difficult to name or has a form of illegibility and find a way to shift that context or embed tension in it so that even if you aren’t able to exactly name why something doesn’t feel right, you know it is off, I think about how to create that through space and object.

You have a way to bring objects into a space devoid of their original intention or people who would normally be around them. The tension could be seen as a dialogue between negative and positive [space] and a question of which is which? There is value to both, the people who are experiencing this space and their loved ones, and then the objects themselves have value as they serve as a ground and resting space for these bodies.

The only function, or reason they exist is to be occupied, and in order to be occupied, there needs to be more people there, so what is that equation?

On a personal note, I’ve visited the women’s prison at Rikers Island on numerous occasions to speak. Those experiences, having gates close behind me the further into the venue I go, has helped me to think about your work in a different way. And it’s powerful to think of that space [the prison, the process of incarceration] to be something that needs to constantly be filled. Maybe now you can talk more about the specifics of what will be in the Regen Projects show.

For my solo exhibition at Regen Projects in LA, as far as the sculptures from this particular series, there are two. They are a form that I’ve used before but in a new color-way. It’s the seat tops and they are configured like jacks, the children’s counting game, or that’s what they sort of resemble and each color is the inverse of each other. Also in the room they will be exhibited in, there is a striped wallpaper that is the same tones of the sculptures which creates a disorientation and dizzying effect. It brings me back to you talking about the positive and negative space whereas the positive and negative are the inverse. That’s one thing that I was playing with in the configuration of Fair Ground as a riff on thinking about art and the use-value of objects and the economic and intellectual value that is placed on art objects. If i’m talking about value there are all these different scales and registers; there is the economic system of furniture for prison, there is an intellectual value now on this object for people entering the art space which is another kind of infrastructure, and there is value in the setting. There is an interplay and that is the pattern in shape of the object and color-way used in the backdrop of these painted walls, do too.

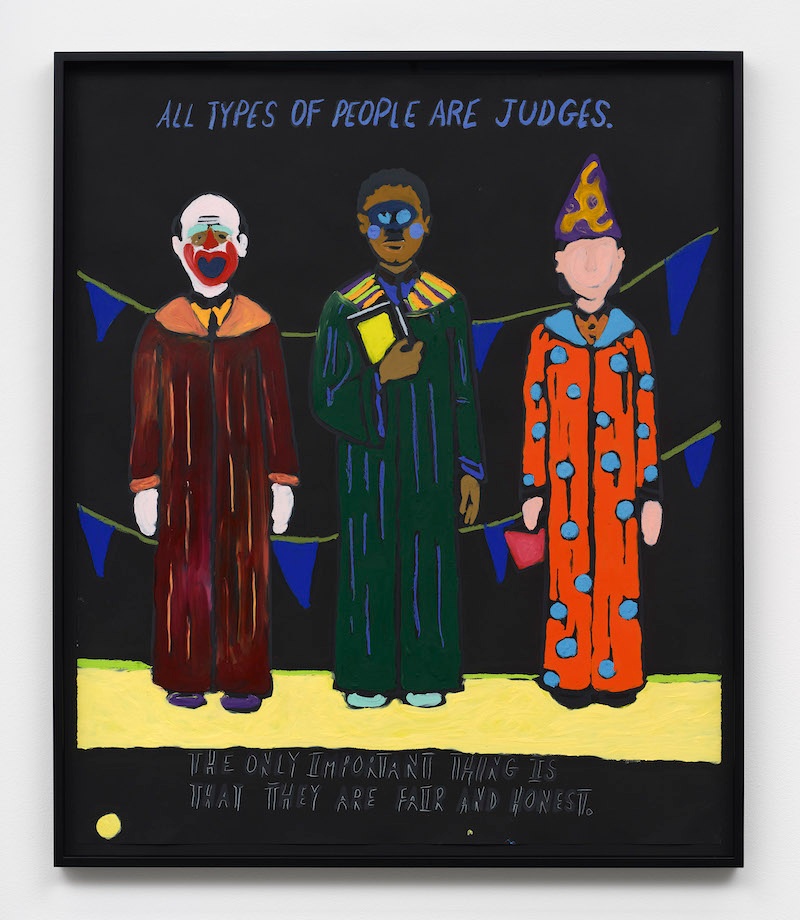

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 129, 2023, screen printing ink, oil pastel, and oil stick on paper, framed dimensions, each: 63 3/4 x 53 1/2 x 2 1/2 inches (161.9 x 135.9 x 6.4 cm)

The first thing that comes to mind for me is camouflage, blending in but also aware of its dimensions.

Yes, that is definitely the intention. And thinking about it as a reference point Op Art too optical illusions that allow things to be concealed and revealed.

There is a specific conceptual quality to the Coloring Book works and an aesthetic difference from your sculpture. As an artist, would you say you are tapping into two parts of yourself to make these?

That’s a good question. I would say that I don’t think I’m in two different places in my brain. I feel like even though I am an introvert, my mind is always doing a hundred things at once. It feels very natural as a way of processing, separate from being an artist, as a person. If something happens I need to look at it from all these different vantage points to gather information and then know how to respond. I’m looking at the world and trying to ask these questions, but I need to process and translate it. In order for me to see something it almost has to be exhaustive, one could say a maximalist approach. Also, working across all of these different materials and series, the system or really any kind of engine of oppression, violence, finance, whatever it is, is persistent and omnipresent. A lot of the works have these numbered naming conventions (editions) and it’s as if to say, Yes this is still happening. This is not a closed conversation or something that we get and then it’s over. It repeats itself every single day.

Concerning physically making the work, it’s the same brain, but I could say embodied in different ways. There are different approaches and different energies that go into the work.

Sable Elyse Smith, Coloring Book 139, 2023, screen printing ink, oil pastel, and oil stick on paper, framed dimensions: 63 1/4 x 53 1/2 x 2 1/2 inches (160.7 x 135.9 x 6.4 cm)

When you come up with the color designs for these paintings, do you work with children?

This series has evolved in so many different directions. For the Regen show there will be a new page that I hadn’t used before. When I first started making these works they were based off of a coloring book that I found, that a child had used. In the beginning I was fixated in thinking about mark-making as a layer that makes you focus on what is the actual content of the material? There is a frenetic freeness of a child’s scrawl. As I’ve made more and more people have seen them, there is space to redact some of the content. The narrative might be present and more established but there are other things that I might focus on and draw out. This could be color and pattern, didactic and binary ideas around power, people, gender or race that’s implied. There is a different type of aesthetic sensibility that is necessary for them. The shadow reference for this show specifically is carnival—the traveling circus, sights of amusement. This show has motifs that point to and reference the absurdity, spectacle, and caricature of those spaces.

When did you find that you truly started to engage your background and experiences in an artistic way?

I feel like, always. Even before I started making art or became an artist I had a writing practice. You can’t escape your life. You can’t escape your history. You can’t escape your context. Even if you are talking about something you weren’t directly effected by, what you have been effected by defines and determines how you respond to life. They can’t be unlinked, and I embrace that.

Sable Elyse Smith Recommends:

My 6 Favorite Things!

Trap music

Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah

Japanese whiskey

Fat Ham (at the Public + The Public Theater)

Artist Tau Lewis’ work

Keeping to myself

Sable Elyse Smith, 9855 Days, 2023, digital c-print, suede, artist frame, framed dimensions: 49 x 41 x 2 inches (124.5 x 104.1 x 5.1 cm)

- Name

- Sable Elyse Smith

- Vocation

- artist, writer, educator

Some Things

Pagination