On being unlikeable in your work

Prelude

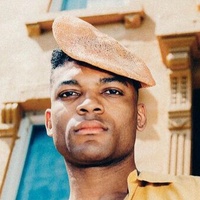

Kevin Killian is a poet, writer, playwright, a member of the New Narrative movement, and the co-founder of Poets Theater, an influential poetry, stage, and performance group based in San Francisco. He has published over a dozen books across a variety of genres, and his novel, Impossible Princess, won the 2010 Lambda Literary Award as the best gay erotic fiction work of 2009. He is married to American novelist, nonfiction author, journalist, and editor Dodie Bellamy.

Conversation

On being unlikeable in your work

Writer Kevin Killian on working across genres, taking inspiration from writing Amazon reviews, and why it took him 23 years to finish his first novel.

As told to Ruby Brunton, 2448 words.

Tags: Writing, Process, Inspiration, Identity, Mentorship.

Congratulations on Fascination, which was recently published by Semiotext(e). I really love how you engage with your reviewers. Some writers appear to me to be more distant, but you seem to really enjoy getting to know and interacting with your readership and critics.

Yeah. I’m grateful to these people who are helping me out by writing about the book, and especially if they like it. There’s nothing I wouldn’t do for them. And in some cases, you know, when you’re my age you already know a lot of these people, so it’s like greeting old friends. My book isn’t meant to win me a lot of new friends, but I hope to keep at least some of the old ones who I have.

What is it about the book that would prevent you from making new friends?

Oh, as I read it again, I’m really the worst person in the world.

Although I don’t know you, I am friends with you on Facebook and I have noticed that you seem really lovely and sweet. And then the Kevin Killian of the book is, as you say, maybe not the greatest guy ever, but you fill him with this incredible humor and honesty. There’s a shower scene where your lover injures himself on some glass, after getting slightly too enthusiastic about positioning. The whole passage ends with this, “I guess.” Kevin says “I guess.”

I guess, and you might still be alive today.

I’m in awe of the detail of the book. Could you tell me a little bit more about how you go about remembering all of those details. Or how much of it is fictionalized?

I remember reading at the University of Buffalo. I read the story “Spurt,” which you’re referring to. It always makes quite an impact, because it’s a very perverse story, and it has these two layers of grief attached to it. When I was living through those events, my boyfriend had killed himself.

In the story I pick up a guy. We both drove our cars to a motel out on Long Island that was quite low level at the time. It was kind of a parody of Fontainebleau. We wound up breaking a mirror, and I was freaked out. My trick was impaled by a shard of glass. I was so freaked out that I just left. And the story ends with me wondering, “Gee, maybe he didn’t make it,” with me scouring the papers to see if somebody had been found dying. After the reading, this one girl came up to me at a party and says, “Did that really happen to you? You left this room where somebody is possibly bleeding to death?” And I was like, “I know. I’m so ashamed and embarrassed about that.” And she slapped me across the face. She said, “You don’t deserve to live.” And that always stuck with me. It’s probably true.

Does it bother you to think that some people might find you to be the worst person in the world after reading? Or is it more important to represent those desires?

I don’t know. I don’t think there is a good answer to that question. I’m lucky to have found Semiotext(e), which has published the work of a lot of transgressive writers. And they’re ready to take on these questions. Or at least, maybe that’s why they went for my writing. It’s hard to say. But they keep finding one French writer more disgusting than the last one. I’m in here trying to do America proud in that sweepstakes.

We can be just as disgusting as the French.

Yeah. We did some horrible things too.

But to me, you seem very warm!

There have been people who, when they’ve met me, or Dodie Bellamy, or both of us, they will say, “You’re not scary and creepy like you are in your books.” Actually we’re very nice people. There’s yet another layer that I’m trying to get at here, which is that maybe all of us in the U.S. feel a certain amount of cooperation, or collaboration, with the big people who have taken over this country and are attempting to take over the world and turn it into a place of evil. That’s something that I have to cop to, even though one does one’s best to resist, and be a resistance. And that’s where some of that feeling comes from.

You and Dodie, who is also a character in the book, were both members of the New Narrative movement that emerged in the 1970s, along with other writers like Cookie Mueller, Kathy Acker, and Gary Indiana. Why do you think this style of writing is having a Renaissance at the moment?

I’m awfully glad this is happening. Ten years ago I think all of us would’ve thought that the New Narrative produced some great work while it lasted, but was then a failed avant-garde because it had led to no actual results that you could measure. And then in the years since I Love Dick was re-published by Semiotext(e), and relaunched in that way, there’s been a wave of critical and scholarly interest in these matters. Dodie and I had the great pleasure of having our papers bought. Our archives were merged together and sold to Yale. I could never have predicted that.

Our New Narrative anthology that came out two years ago, Writers Who Love Too Much, was the idea of our publisher, Nightboat Books, to capitalize on this renewed interest in academia on the work that we did in the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s. It’s just been marvelous, and it’s led me to a second life as a public figure, I guess. I could never have predicted that any of our abysmal goings on would’ve led to this interest.

I’m also wondering if there’s something to do with a renewed desire for honesty and self-reflection in an age where those things are greatly lacking in the wider cultural climate.

It would be nice to think so. Some have pointed to the literary qualities in our works that they’ve come to admire. Not just the “Brace yourself, I’m going to tell you something terrible…” attitude that we began our books with.

I mean, another thing I should say—and a lot of this is written in the introduction to our book Writers Who Love Too Much—is that we’re living in a time where all of the walls are breaking down between genres. And that’s something that we were doing 35 years ago. There was this idea that there should be no more bookstore categories that say non-fiction, memoir, essay, drama, short story, novel, poem. Why not be as contradictory as you can? The human mind is organized in that way, so you can think a million thoughts all at once. And I think that that blurring of genre is ultimately what led to any interest in New Narrative.

There’s a quote from Dodie that says, “I was writing linked poems that kept getting longer and more narrative.” And that’s when she started writing essays. I was wondering if, as someone who writes poetry, short stories, memoirs, and novels, as you do, if you similarly have any kind of approach to deciding which one to do? Is there a method to the madness, so to speak?

Yes, there’s a method to deciding what I’m going to be doing ultimately, but a lot of it I test out first. Have you read any of my Amazon reviews? I’m in the Amazon hall of fame. I’m going to be in few halls of fame in my life, but that is one of them. At one point I was one of the top 100 Amazon reviewers. That means that I’ve reviewed literally thousands of products on Amazon. I have often used Amazon reviews as a springboard to doing other kinds of writing projects. So when you read them, yeah, they’re reviews of a sort, but they also seem like novels. They’re poems. They’re essays about life. I adopt a different persona in them. You know, you’re talking about a couple of hundred words at the longest. So yeah, I get a lot of my kinks out there, on Amazon. Three of my books, one of my most popular books, are my selected Amazon reviews, Volumes I, II, and III.

That’s a great strategy. It reminds me of a section in the memoirs where you’re talking about your friendship with George, a young writer. His advice for writing a novel was, “Just pretend you’re writing a letter to me.” He also has this other method of retelling film plots. What do you think of this advice? Have you used it? What do you think about these kind of prompts to get your writing happening.

Yes, I advise using both of them. He taught me everything that I know about writing. He was just a classmate of mine in high school and I was in love with him. Part of my reason for writing Bedrooms Have Windows is that I had lost touch with him. This was in the days before computers. I figured that if I published a whole book that was basically, “Please, let me hear from you,” he might read it. A mutual friend of ours read the book, and saw my plea. He recognized the name. I call him George Gray in the book, because I was writing while he was alive, but his real name was Terry Black. “Black” and “Gray,” they’re kind of the same. My friend sent me back the obituary, saying that Terry had died of AIDS in Virginia. So I don’t think he ever did read my book. But his daughter did, and we’re friends on Facebook today.

Your first novel, Spread Eagle, took 23 years to write as you were waiting to come up with the ending.

Yeah. And finally I did. I get a lot of advice from my dreams. I dreamed the ending of Spread Eagle. And then I was able to finish it, which was good, because by then I had a contract to produce it. It just kind of wrote itself. After all those decades of opening this door with a novel in it, I was finally able to shut it after a few more pages were written.

What did you do in the meantime? Did you just work on other projects and wait for that dream?

Yeah. The ’90s were spent largely in hoping for a cure for AIDS. We didn’t get a cure, exactly, but we got enough. We got a lot of extraordinary drugs that would minimize the suffering of people who had AIDS. And also eventually prevent people from getting the HIV virus.

I started writing a lot of poetry. I’ve published four books of poems. I made my work with the San Francisco Poets Theater, an engaged group of like-minded people. Artists. Writers. Poets and artists. All kinds of people would get out onto a stage and recite things, learn their parts, read their parts off of a script. I’ve written over 50 plays for the San Francisco Poet’s Theater. I was also writing stories and reviews. I punched into the art world and started writing a lot of art criticism. So in a way my life, my artistic life, blossomed in the ’90s, but the results were far and few between. Years would go by before I would publish a book.

You said it was so wonderful to have the artist John Neff create a visual exhibition based on Spread Eagle, because, according to your quote, “Like every novelist we all think our work is tragically ignored.” I love that quote because I think no matter what level you are at as a writer—whether you’ve had one book published or a million books published—there seems to be a constant hunger for more. Can you even imagine what a feeling of satisfaction as a novelist might be like? Or do you think that part of never reaching that feeling, or the constant striving for it, is part of what continues to fuel the work?

Oh, I wonder. I don’t know if I’ll write another novel. That’s for sure. I thought it was because I’m too old now, and I don’t have the stamina to work on something that would take me that long. I have ideas, but nowadays they’re the kind of ideas that would be better as a short story. Or maybe a 30-page miniature novel.

That might only take six years.

Yeah. Also, maybe some of it is feeling like, “Oh, you should do the thing people like you the most for.” I’ll have to think more about that—is there anything that’s still burning in me to get out? Or is it time for me just to turn over and help the young people that I know? As I myself was helped so much by older people when I was a young man.

Can you tell me a little about your next book?

Stage Fright. It’s all about the people who aren’t actors, who played in our plays. Just regular artists and writers and poets. We can’t memorize the plays, so we have to get up there with the script in our hands. And somehow that allows us all to act, act, act in a much better way than if we had been in the actor’s studio.

So another blurring of genre?

Yes. For example, Sarah Schulman was in one of these plays. Eileen [Myles] played in several of them. I wrote one for the author Mary Gaitskill. She played Tippi Hedren, the Hitchcock actress, who is remembering when Hitchcock used to molest her on the set of The Birds and Marnie. Nobody who saw her performance would ever forget it. It remains the best acting job any of us have seen.

Kevin Killian recommends:

-

Gary Giddins, Bing Crosby: Swinging on a Star: The War Years 1940-1946 (Little, Brown & Company)

-

Patty Jenkins, I Am the Night (TNT Network, Monday nights)

-

The de Young (Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco), Specters of Disruption, curated by Claudia Schmuckli (through April 30, 2019)

-

Dennis Cooper and Zac Farley, Permanent Green Light (film)

-

Critical Resistance Oakland, fighting for prison abolition in commonsense terms

-

Kylie Minogue feat. Gente De Zona, “Stop Me From Falling”

- Name

- Kevin Killian

- Vocation

- Writer

Some Things

Pagination