As told to Whitney Matheson, 3159 words.

Tags: Comics, Inspiration, Process, Beginnings, Income, Multi-tasking, Creative anxiety.

On the power of creative communities

Cartoonist and playwright Dean Haspiel on the value of community building, why imposter syndrome can sometimes be a good thing, and trying to tell stories that can stand the test of time.You recently returned from Yaddo, an artists’ community where you were able to immerse yourself in creative work. What did you learn there that you can apply back in the “real world?”

Number one is discipline. It gives you a space to achieve your work and to spend a certain amount of hours not worrying about anything else. But also, it creates a certain kind of anxiety. You feel like… Oh, what’s the term when you feel fake? Like you have to justify who you are as an artist. Because you get into this space, you meet a bunch of people—and after a while, you realize everyone’s a genius, basically.

Are you talking about imposter syndrome?

That’s right. And that’s a good feeling, because it means it’s keeping you on your toes. And then it amps up, like, “Well, what is it that I’m trying to say?” The other thing that’s wonderful is that I get access to things I never even knew existed, like other art forms and types of people and the things they are concerned about. It just opens up the floodgates. The older you get, the more you start leaning toward your comfort zones, and the things that feel safe. But this place breaks open the boundaries. It’s like a laboratory of different kinds of disciplines and artists and ideas.

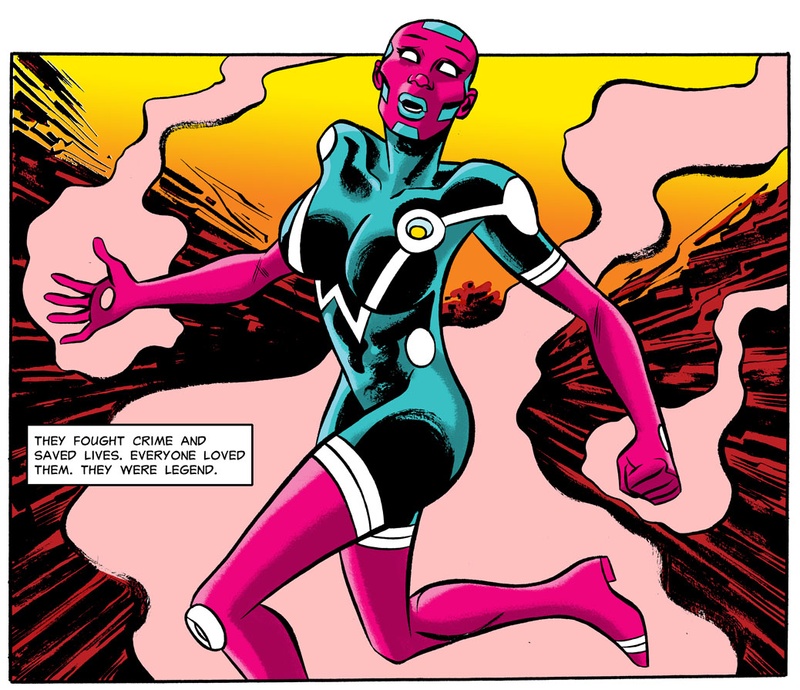

A panel from 2019’s The Red Hook Vol. 2: War Cry. (Image Comics)

You’re known for your creative collaborations. What do you think makes for a good collaborator?

I feel like a good collaboration is when you identify each other’s virtues and you yield to each other’s virtues—but while that’s happening, you can challenge each other as artists and, hopefully, push each other in directions that you never would have done as a solo artist. I have considered stuff that I never would’ve considered because of collaboration.

I think collaboration is really important, not only for artists of all disciplines, but all auteurs, because it reminds you to push yourself. Sometimes I’ll put on another hat and say, “Well, what if this invaded my process? Or what if this was suggested?” Which is why it’s also important, I believe, to talk about your art as you’re making it to your peers or other people.

I know some people feel like, “I don’t want to be influenced. I have my idea, and I want to cocoon myself so I can create the butterfly.” But for me, the butterfly needs the interaction of other people. My art isn’t finished until you read it. You may not like it—or hopefully you will—but it’s not complete until it’s communicated to someone else.

It surprises me to hear you talk about feeling like an imposter, because you’ve experienced some success.

I’ve been in this long enough now to understand that part of success is who you know. It is geography and who is jurying our processes and our systems in a lot of ways. If you get to be buddies with someone, suddenly you could blow up with no merit to your work, and that happens all the time.

So I do wonder, partially, “Did I earn the space I’m in?” Even though financially I’m still eating peanut butter sandwiches and takeout Chinese food, on paper I’m a success, because right now I’m in this awesome autonomous space where I’m writing and drawing something that I own and am getting paid for. That is the prize, isn’t it? That’s what success is.

Would I like to have a lot more people indulging my work? Absolutely, but I also understand that we live in a niche world right now. I don’t even know if my work should impact the world. I just want it to be a testament of my life at the end of the day.

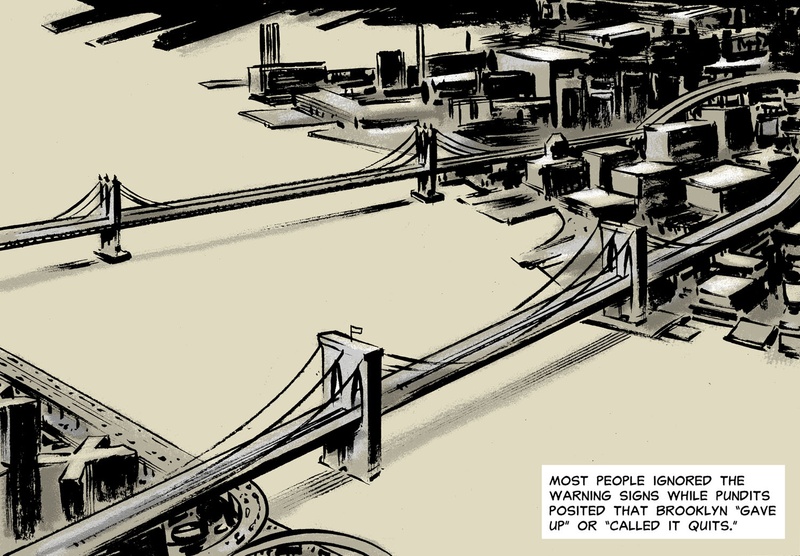

An image from The Red Hook Vol. 1: New Brooklyn, published in 2018. (Image Comics)

How do you define success, and is that different from how you may have defined it 20 years ago?

If I had a lot of money right now, I would want to be comfortable and not have the anxiety that one has as a freelancer, not knowing what your next job is. But I [also] feel like I would be a little more socialist about it and try to create communities kind of like a Yaddo, or maybe help those kinds of places, because we need to uplift each other. That’s why I have studio spaces: to not only go to a space that’s energized by creativity, but so I can also in some way pay it back, because I have been offered those energies and chances in my life. But at the end of the day, it shouldn’t just be handed to you. You’ve got to show up with the work.

Who are some people who have taught you the most about the creative process?

In 1985, I was in my senior year of high school. I had gone to the High School of Music & Art in Harlem, and in my senior year, Music & Art married performing arts and became LaGuardia [High School of Music & Art and Performing Arts]. So that first year, we were the graduating class.

At three o’clock after school, it’s me and Larry O’Neil, my good buddy who’s a writer. His father is [comics writer/editor] Denny O’Neil, which is why we got hip to this studio down in the Garment District that housed Howard Chaykin, Walter Simonson, and previously had Frank Miller and Jim Starlin. Down the hall was Bill Sienkiewicz with Denys Cowan and Michael Davis, and they needed some assistants. So suddenly, I go from wanting to draw comics since I was 12 years old to five years later, actually working on comics that were coming out on a monthly basis: American Flagg!, The Mighty Thor, New Mutants, Elektra: Assassin.

It was a very heady time. Also, what was interesting about that was I was going to an arts high school where they didn’t teach comics—in fact, they basically rejected comics. I was learning certain graphic disciplines and fine art, painting, sculpture… drawing comics in the corner of notebooks and whatnot, with teachers just looking at me like, “You don’t want to do that.” By the way, they’re not totally wrong, because it is hard to make a career out of comics.

Anyway, I’m going downtown, hanging out with these incredible artists and writers, learning by doing, by experience. Community is really key to all of this. You pay it forward. It’s not about hotdogging or being like… I don’t like hierarchies necessarily, but it’s just about uplifting each other in some way and being truthful.

An image from The Red Hook Vol. 1: New Brooklyn, published in 2018. (Image Comics)

Going back to the imposter thing, we wear our influences on our sleeves, and I think part of what I’m doing when I’m looking in the mirror is like, “Am I doing too much Jack Kirby? Too much Howard Chaykin? Am I writing too much like my favorite writer?” And so you’re trying to shrug that off and find who you are through the process of copying. I mean, isn’t the definition of style when you have failed at copying your influences and abandon them? That’s when you arrive at your own style.

You mostly use analog materials to create a lot of digital work. Why is that?

Because I learned comics in an analog way: pen, paper, ink, erasing. It’s funny, because I’ve actually had more success digitally than in print. If you look at my numbers and my sales in print, they’re middling to almost still in the red a lot of the time. But online, I’m all over the place.

I feel like I was a progenitor of personal webcomics when we launched ACT-I-VATE [in 2006]. One of the things we were pitching was, “Well, you can read these for free.” It’s because it’s a different kind of currency; not everything is money, you know? If I can get eyes on something or if I can make you a lifelong fan to whatever I do next, whether it’s free or you get to pay for it, that’s part of the relationship that I’m trying to build and grow.

What are some mistakes you think you made as a younger artist?

Not believing in myself. There was a stigma attached to the art form I loved so much, and so I was probably negotiating, “Is this a smart route to go down—dedicating my life and making the sacrifice to be an artist in New York City, the most expensive place on Earth?”

Comics are hard. It’s not just drawing, it’s not just writing, it’s not just coloring and lettering. It’s a bunch of disciplines, and it’s how to convey story the best you can. But it’s also an innate art form. A baby can start drawing comics. An old person can start drawing comics, because it’s just words and pictures and how you convey that.

In terms of mistakes, I’m really excited that I’ve turned a corner in my career where I’m writing more than drawing. I do wonder, had I tried to write more stuff earlier on, would I be in a better position as an auteur? I think some of my favorite auteurs blew up at age 30, and I’m just kind of getting to that place in my mid-50s. I do wonder if earlier on had I believed in myself and taken more chances and learned how to be a better storymaker… but that’s my life. I can’t go backwards.

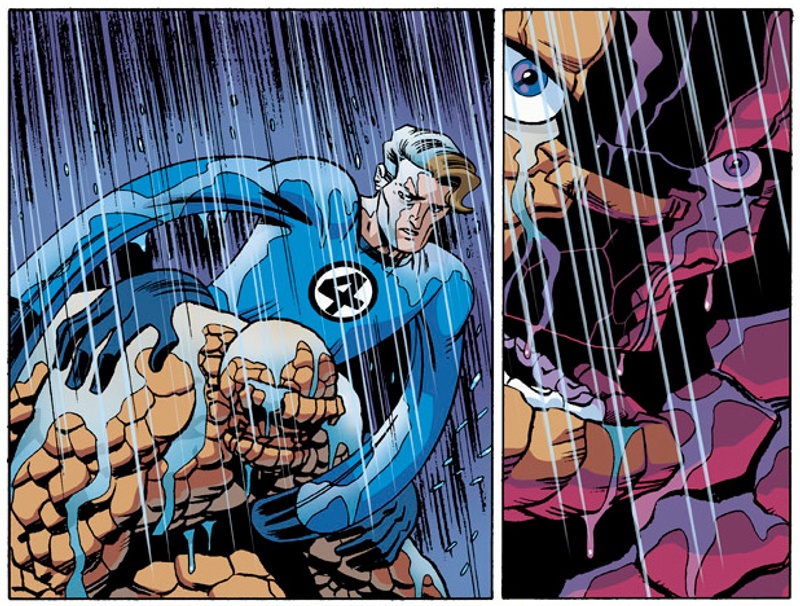

A panel from a 2015 issue of Fantastic Four, drawn by Dean Haspiel. (Marvel Comics)

Would you say it’s easier to make a living now that you have so much experience?

I think it’s a little more difficult, because who reads comic books? I’m lucky to be in a position right now where Webtoon is funding me to create something I own, but at some point that could go away. And then what do I do? Some kind of crowdfunding? Or do I try once again to draw other people’s IP—intellectual property—with Marvel, DC, Archie, and so on?

I do think it’s a lot harder to work in comic books. DC and Marvel have been around for 80-some odd years, so they’re turning their comic books into TV shows and movies now. I think they’re struggling to sell comic books. It’s really, really hard. And I know there’s other digital platforms, but… Actually, I don’t think I’m expert enough to answer that, but I do know that I’ve worked for so many different publishers that it feels like it’s become more and more difficult.

How do you handle pressure to come up with “the next thing?”

It’s a double-edged sword, because what you’re wrestling with is, “Am I doing this for me, or am I doing this for you?”

I feel like I’m trying to do it for both, so I need to honor whatever the muse tells me to do. Like, what is really interesting me enough that not only do I develop some kind of a pitch or a package… and then to dive in for over a year to create something that you are going to read in about 45 minutes. And hopefully, you’ll even want to pick it up to read it for 45 minutes. Right? That’s some fucked-up shit right there.

And so, because I understand that a lot of our entertainment is disposable, am I purposely creating a disposable product, or am I trying to create something that has some long-lasting value? Consciously, with the longer projects I do ask myself, “Am I creating something that you can revisit 20 years from now, or after I’m dead?” Even if it’s a little dated, I feel like I’m trying to write stories that are emotionally true, that resonate through time.

That probably wasn’t in your mind when you were young—or was it? To make something that’ll stick around?

Right. I mean, I think about Adrian Tomine, whose early work just was so profound, and then he became a master. There’s something undeniable about those early Optic Nerve comics. And yes, he has great stuff that’s very considered and qualified, almost Kubrickian, where it’s perfection. But the imperfection of his early work still resonates with me.

No one’s telling you what not to do, but then when you start to have a certain abundance of work, people will say, “Well, I liked that early stuff you did. Can you do that again?” I polarized people with my work because I love superheroes, but I also love memoir. The Red Hook and Beef With Tomato, for instance, are very different pieces of work. Although I see the similarity, other people don’t, and it’s because genre or certain trappings can make people decide they don’t want to be involved.

I think a lot of artists are struggling because it’s a very stressful time. Aside from what’s going on in their personal lives, there’s just a lot of sadness and tragedy.

Comics have definitely been a therapy for me. Also, comics are great, just like a lot of art forms, for commenting on the world at a certain time. I try to not only entertain, but let you escape a little bit from the daily stuff and sneak in a little commentary.

For me, in a way, what I’m doing is what comics did for me as a kid. I didn’t have the happiest childhood, so I gravitated toward comics. The Fantastic Four was a family: That was beautiful, they were adventurers, and they did incredible things. The Thing was my favorite comic book character, this misunderstood monster with a heart of gold. What was great about Marvel Comics is that there wasn’t a black-and-white world, it was all gray with a lot of colors on top.

What I tend to do is remind myself, “Well, maybe I could help someone else escape, but also somehow have it relate to their lives by excavating the universal truths.”

We all keep working because we have to make a living, but have you ever had times when you felt stuck? What helps you get out?

Getting stuck can come in different forms. [One] is, “Well, what I’m going to do next?” And then if you get the opportunity to do something next, can you fulfill that? I feel like being a freelancer requires being a really great liar, not only to your employer, but to yourself. I lie all the time. When an employer or a client calls up and they need a certain thing by a certain time, I go, “Sure. Yeah, of course I can do that.”

But when it comes to creativity what you have to do, ultimately, is turn that into encouragement and a rallying force of thunder that will get your creative juices going. And you have to fall in love with every major project you do, or else it will stink.

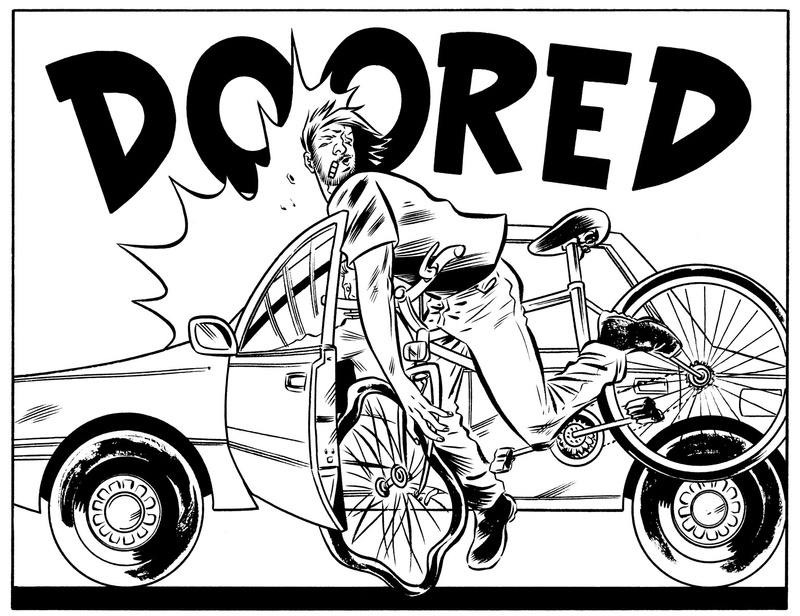

An image from Dean Haspiel’s 2015 graphic memoir, Beef With Tomato. (Alternative Comics)

What do you find frustrating about what you do?

I’m kind of a gregarious people person, and to do what I do means basically chaining yourself to an art table or to a laptop, alone. Even though I share a studio to draw, eventually at some point you got to stop the jibber-jabber and get to work. So actually sitting and drawing is kind of defeating my personality in certain ways.

I wonder if that’s why you’re stepping back from drawing a bit, because that’s far more time-consuming than the writing.

Yeah. With drawing, I’m hoping to eventually create a shorthand that I’m really happy with, because, ultimately, what you’re doing when you’re reading a comic is reading the words and kind of glancing at the artwork and turning pages. I never have really drawn anything that’s supposed to stop you in your tracks as a reader and go, “Wow, look at that art!” Because what it does is it takes you out of the story.

I want to immerse you. I want you to be darting across the panels and turning pages, because I want to consume you with story. My art should be the writing, and if I can create an excellent kind of shorthand, I’ll be happier with sitting down and drawing. It also could mean that I’ll be drawing faster, but I’m not sure.

In your stories, horrible and terribly sad things may happen, but they often end on a note of hope or love or acceptance—

Or redemption.

Why do you think that’s important?

I did indulge the darkness for a while in my comics. At some point I realized, “Well, we’re putting these things out there, and they do have a certain power.” And maybe my responsibility to not only the art, but to me, is to promote some kind of goodwill. If the characters can get through some obstacles, as we do in real life, and the payoff is some kind of redemption or understanding—it doesn’t have to necessarily be positive—then there’s a sense of hope. And I try to promote hope in my work.

Dean Haspiel recommends:

-

Jack Kirby - Co-creator of Captain America, the Marvel Universe, and some DC Comics characters, Jack Kirby’s unparalleled, PTSD-inspired, cosmic-fueled imagination asked the hard questions about men, monsters, and gods … and dared to answer them.

-

Prince - Prince was the soundtrack to my puberty and taught me everything about dance, music, sex, romance, tolerance, and inclusiveness.

-

Sergio Leone - His spaghetti westerns blurred the vistas between flesh and landscape, molten mesas and human pores, baked blood and boiled sweat, squinting eyes and smoking guns, and recorded it all on the bedrock of Earth’s scorched earth. Leone’s Once Upon A Time In The West competes with my other favorite movie, Elia Kazan’s On The Waterfront.”

-

Bea Arthur - For years, I carried her picture in my knapsack. Now, I carry her attitude in my heart. Bea Arthur’s Maude was a flawed, yet righteous, middle-aged Valkyrie emerging as a taboo-breaking feminist—and television’s first female hero.

-

Wo Hop - Since I was an embryo in my mother’s stomach, this underground Chinatown establishment has nourished me through thick and thin. The day I croak, there’s a very good chance my stomach will contain beef with tomato over white rice and steamed pork dumplings.